m (alteração, a pedido da Fany, de 150 para mais de 160 línguas indígenas) |

|||

| (7 intermediate revisions by 2 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Título | Languages}} | {{Título | Languages}} | ||

| − | More than | + | More than 160 languages and dialects are spoken by the Indigenous peoples in Brazil today. They are part of the near 7,000 languages spoken today in the world (SIL International, 2009). Before the arrival of the Portuguese, however, only in Brazil that number was probably close to 1,000. |

In the process of colonization of Brazil, the Tupinambá language, the most widely spoken along the coast, was adopted by many colonists and missionaries, taught to Indians grouped in the missions and recognized as Língua Geral. Today, many words of Tupi origin are part of the vocabulary of Brazilians. | In the process of colonization of Brazil, the Tupinambá language, the most widely spoken along the coast, was adopted by many colonists and missionaries, taught to Indians grouped in the missions and recognized as Língua Geral. Today, many words of Tupi origin are part of the vocabulary of Brazilians. | ||

| Line 14: | Line 14: | ||

== Trunks and branches == | == Trunks and branches == | ||

| − | Among the approximately | + | Among the approximately 160 Indian languages spoken in Brazil today, some have more similarities with each other than with others, which reveals common origins and diversification processes that took place over the years. |

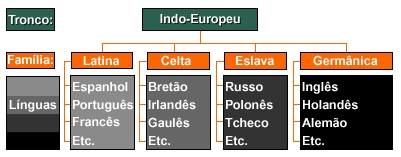

Experts on the knowledge of languages (linguists) express the similarities and differences among them through the idea of linguistic branches and families. Branches mean languages whose common origins are very old, and the similarities among them are very subtle. Among the languages of the same family, on the other hand, the similarities are greater, which is the result of a separation that took place not so long ago. See the example of the Portuguese language: | Experts on the knowledge of languages (linguists) express the similarities and differences among them through the idea of linguistic branches and families. Branches mean languages whose common origins are very old, and the similarities among them are very subtle. Among the languages of the same family, on the other hand, the similarities are greater, which is the result of a separation that took place not so long ago. See the example of the Portuguese language: | ||

| Line 39: | Line 39: | ||

<br style="clear: both;"/> | <br style="clear: both;"/> | ||

=== Macro-Jê branch === | === Macro-Jê branch === | ||

| − | + | {{Img | |

| + | |12 | ||

| + | |http://img.socioambiental.org/d/282531-3/tronco_macro-je.gif|Famílias linguísticas do tronco Macro-Jê | ||

| + | }} | ||

<br style="clear: both;"/> | <br style="clear: both;"/> | ||

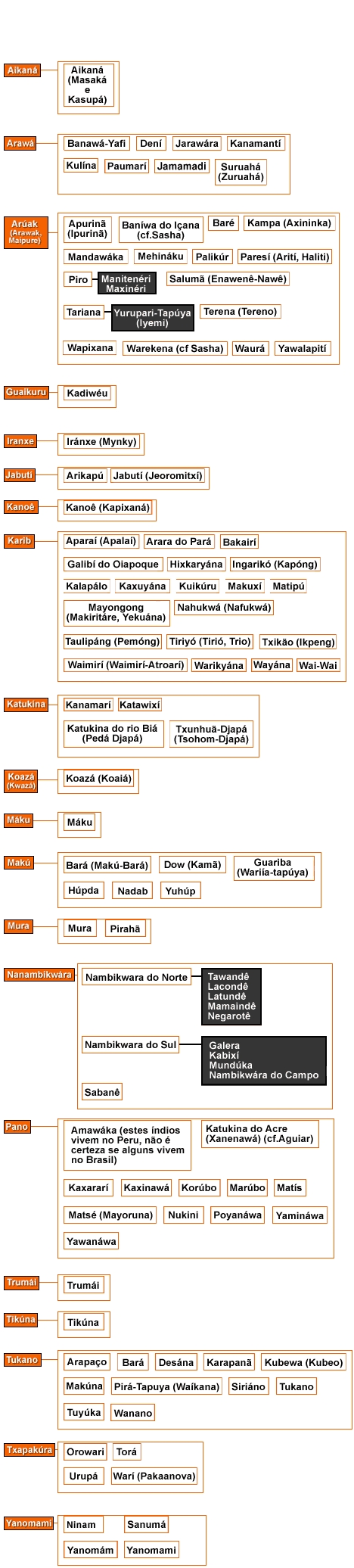

| − | + | === Other families === | |

| − | + | {{Img | |

| + | |12 | ||

| + | |http://img.socioambiental.org/d/296893-1/outras-familias.jpg|Outras famílias linguísticas | ||

| + | }} | ||

| + | |||

| + | == Multilinguism == | ||

| − | ''' | + | {{Lead | Text adapted from '''RODRIGUES, Aryon Dall´Igna''' – ''Línguas brasileiras: para o conhecimento das línguas indígenas''. Edições Loyola, São Paulo, 1986.}} |

Indigenous peoples in Brazil have always been used to situations of multilinguism. That means that the number of languages spoken by an individual can vary. There are those who speak and understand more than one language and those who can understand several but are able to speak just one or a few of them. | Indigenous peoples in Brazil have always been used to situations of multilinguism. That means that the number of languages spoken by an individual can vary. There are those who speak and understand more than one language and those who can understand several but are able to speak just one or a few of them. | ||

| Line 61: | Line 69: | ||

In contexts such as that, sometimes one of the languages becomes the most widespread means of communication (what experts call lingua franca) and is used by everyone, when together, in order to understand each other. For example, the Tukano language, which belongs to the Tukano family, has a privileged social position among the Eastern tongues of this family because it has become the general language, or lingua franca, of the Uaupés area, and is the vehicle of communication between speakers of different languages. It has superseded other tongues – completely, in the case of Arapaço, or almost completely, such as in the case of Tariana. | In contexts such as that, sometimes one of the languages becomes the most widespread means of communication (what experts call lingua franca) and is used by everyone, when together, in order to understand each other. For example, the Tukano language, which belongs to the Tukano family, has a privileged social position among the Eastern tongues of this family because it has become the general language, or lingua franca, of the Uaupés area, and is the vehicle of communication between speakers of different languages. It has superseded other tongues – completely, in the case of Arapaço, or almost completely, such as in the case of Tariana. | ||

| − | There are cases in which it is Portuguese that is used as lingua franca. In some areas of the Amazon Region, for example, there are situations in which different Indigenous peoples and the local population speak Nheengatu, the Amazonian General Language, when speaking among themselves.== General | + | There are cases in which it is Portuguese that is used as lingua franca. In some areas of the Amazon Region, for example, there are situations in which different Indigenous peoples and the local population speak Nheengatu, the Amazonian General Language, when speaking among themselves. |

| − | + | ||

| + | == General languages == | ||

When the Portuguese colonization of Brazil started, the language of the Tupinambá Indians (of the Tupi branch) was spoken in a large area along the Atlantic coast. Thus already in the beginning of the 16th Century Tupinambá was learned by the Portuguese, whom at the time were a minority among the Indigenous population. With time, the use of that language, called Língua Brasílica – Brasilica Language -, was intensified and eventually became so widespread that it was used by almost the entire population that was part of the Brazilian colonial system. | When the Portuguese colonization of Brazil started, the language of the Tupinambá Indians (of the Tupi branch) was spoken in a large area along the Atlantic coast. Thus already in the beginning of the 16th Century Tupinambá was learned by the Portuguese, whom at the time were a minority among the Indigenous population. With time, the use of that language, called Língua Brasílica – Brasilica Language -, was intensified and eventually became so widespread that it was used by almost the entire population that was part of the Brazilian colonial system. | ||

| Line 69: | Line 78: | ||

Around the second half of the 17th Century, Língua Brasílica, already considerably altered by its current usage by mission Indians and non-Indians, became known as Língua Geral – General Language. But there existed, in reality, two Línguas Gerais in colonial Brazil: the Paulista (from São Paulo) and the Amazônica (Amazonian). It was the former that has left strong marks in the Brazilian popular vocabulary still in use today (names of objects, places, animals, foods etc.), so much so that many people imagine that ‘the language of the Indians was (only) Tupi’. | Around the second half of the 17th Century, Língua Brasílica, already considerably altered by its current usage by mission Indians and non-Indians, became known as Língua Geral – General Language. But there existed, in reality, two Línguas Gerais in colonial Brazil: the Paulista (from São Paulo) and the Amazônica (Amazonian). It was the former that has left strong marks in the Brazilian popular vocabulary still in use today (names of objects, places, animals, foods etc.), so much so that many people imagine that ‘the language of the Indians was (only) Tupi’. | ||

| − | + | ||

| + | === Paulista General Language === | ||

The Paulista General Language had its roots on the language of the Tupi Indians of São Vicente and of the Upper Tietê River, which differed somewhat from the language spoken by the Tupinambá. In the 17th Century, it was the language spoken by the explorers of the interior of the continent, known as bandeirantes. Through them the Paulista General Langauge penetrated areas in which the Tupi-Guarani Indians had never been to, thus influencing the daily language of a great many Brazilians. | The Paulista General Language had its roots on the language of the Tupi Indians of São Vicente and of the Upper Tietê River, which differed somewhat from the language spoken by the Tupinambá. In the 17th Century, it was the language spoken by the explorers of the interior of the continent, known as bandeirantes. Through them the Paulista General Langauge penetrated areas in which the Tupi-Guarani Indians had never been to, thus influencing the daily language of a great many Brazilians. | ||

| − | + | ||

| + | === Amazonian General Language === | ||

Rooted on the language spoken by the Tupinambá Indians, this second General Language developed at first in Maranhão and Pará in the 17th and 18th centuries. Until the 19th Century, it was the language used for catechism and for Portuguese and Luso-Brazilian social and political actions. Since the end of the 19th Century the Amazonian Língua Geral is also known as Nheengatu (''ie’engatú ''= ‘ good language’). | Rooted on the language spoken by the Tupinambá Indians, this second General Language developed at first in Maranhão and Pará in the 17th and 18th centuries. Until the 19th Century, it was the language used for catechism and for Portuguese and Luso-Brazilian social and political actions. Since the end of the 19th Century the Amazonian Língua Geral is also known as Nheengatu (''ie’engatú ''= ‘ good language’). | ||

| − | In spite of the many changes it has suffered, Nheengatu continues to be spoken today, especially on the Negro River basin (Uaupés and Içana rivers). Besides being the mother tongue of the local population, it still maintains the character of language of communication between Indians and non-Indians, and between Indians of different languages. It is also a tool for the ethnic assertion of peoples whose languages have been lost, such as the Baré, the Arapaço and others.== School and writing == | + | In spite of the many changes it has suffered, Nheengatu continues to be spoken today, especially on the Negro River basin (Uaupés and Içana rivers). Besides being the mother tongue of the local population, it still maintains the character of language of communication between Indians and non-Indians, and between Indians of different languages. It is also a tool for the ethnic assertion of peoples whose languages have been lost, such as the Baré, the Arapaço and others. |

| + | |||

| + | == School and writing == | ||

Prior to the establishment of systematic contact with non-Indians, the languages of the Indigenous peoples who live in Brazil were not written. With the development of projects of school education conceived for Indians, this has changed. This is a long story, which raises questions that ought to be thought upon and discussed. | Prior to the establishment of systematic contact with non-Indians, the languages of the Indigenous peoples who live in Brazil were not written. With the development of projects of school education conceived for Indians, this has changed. This is a long story, which raises questions that ought to be thought upon and discussed. | ||

| − | + | ||

| + | === A bit of history === | ||

The history of Indigenous school education shows that, in general, schooling had always had the goal of integrating the Indigenous populations into the greater society. Indian tongues were seen as the biggest obstacle for such integration. Thus the function of the school was to teach Indians student how to speak, read and write in Portuguese. | The history of Indigenous school education shows that, in general, schooling had always had the goal of integrating the Indigenous populations into the greater society. Indian tongues were seen as the biggest obstacle for such integration. Thus the function of the school was to teach Indians student how to speak, read and write in Portuguese. | ||

| Line 86: | Line 100: | ||

Even in such cases, however, as soon as the students learned how to read and write, the Indigenous language was no longer used in the classroom, since the mastering of Portuguese was the main objective. So it is clear that, given that situation, school has contributed for the weakening, depreciation and, as a result, the disappearance of Indigenous tongues. | Even in such cases, however, as soon as the students learned how to read and write, the Indigenous language was no longer used in the classroom, since the mastering of Portuguese was the main objective. So it is clear that, given that situation, school has contributed for the weakening, depreciation and, as a result, the disappearance of Indigenous tongues. | ||

| − | + | ||

| + | === Indigenous languages at school === | ||

On the other hand, school can also be an element capable of encouraging and favoring the permanence or revival of Indigenous languages. | On the other hand, school can also be an element capable of encouraging and favoring the permanence or revival of Indigenous languages. | ||

| Line 95: | Line 110: | ||

In order for that to happen it is necessary that the entire Indigenous community – and not only the teachers – wish to keep its traditional language in use. Thus schooling is an important but limited instrument: it can only contribute for the survival or disappearance of those tongues. | In order for that to happen it is necessary that the entire Indigenous community – and not only the teachers – wish to keep its traditional language in use. Thus schooling is an important but limited instrument: it can only contribute for the survival or disappearance of those tongues. | ||

| − | + | ||

| + | === The Portuguese language at school === | ||

Mastering the Portuguese language at school is one of the tools that Indigenous societies have for interpreting and understanding the legal bases that conform life in Brazil, especially those that refer to the rights of Indigenous peoples. | Mastering the Portuguese language at school is one of the tools that Indigenous societies have for interpreting and understanding the legal bases that conform life in Brazil, especially those that refer to the rights of Indigenous peoples. | ||

| Line 102: | Line 118: | ||

For the Indigenous peoples that live in Brazil, the Portuguese language can be an instrument for the defense of their legal, economic and political rights; a means to expand their own knowledge and humankind’s; a recourse for them to be recognized and respected nationally and internationally in their diversity; and an important channel for relating with each other and taking common political stances. | For the Indigenous peoples that live in Brazil, the Portuguese language can be an instrument for the defense of their legal, economic and political rights; a means to expand their own knowledge and humankind’s; a recourse for them to be recognized and respected nationally and internationally in their diversity; and an important channel for relating with each other and taking common political stances. | ||

| − | + | ||

| + | === The introduction of writing === | ||

If oral language, in its various manifestations, is part of daily life in practically every human society, the same cannot be said regarding written language, since the activities of reading and writing can normally be performed only by people who were able to go to school and while there found favorable conditions to realize how important the social functions of those activities are. | If oral language, in its various manifestations, is part of daily life in practically every human society, the same cannot be said regarding written language, since the activities of reading and writing can normally be performed only by people who were able to go to school and while there found favorable conditions to realize how important the social functions of those activities are. | ||

| Line 122: | Line 139: | ||

But a strong argument for the introduction of written usage of Indigenous languages is that to limit those tongues to exclusively oral uses means to keep them in a situation of no prestige and of low practical applications, thus reducing their chances of survival in contemporary situations. And writing them also means that those languages will be resisting the ‘invasions’ made by Portuguese. In fact, they will themselves be invading the realm of a major language and conquering one of its most important territories. | But a strong argument for the introduction of written usage of Indigenous languages is that to limit those tongues to exclusively oral uses means to keep them in a situation of no prestige and of low practical applications, thus reducing their chances of survival in contemporary situations. And writing them also means that those languages will be resisting the ‘invasions’ made by Portuguese. In fact, they will themselves be invading the realm of a major language and conquering one of its most important territories. | ||

| − | '''[Text condensed and adapted from the document ''Referencial curricular nacional para as escolas indígenas'', Brasília: MEC, 1998]''' | + | '''[Text condensed and adapted from the document ''Referencial curricular nacional para as escolas indígenas'', Brasília: MEC, 1998]''' |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | The | + | == See also == |

| + | [[ The work of linguists]] | ||

| Line 316: | Line 154: | ||

{{DISPLAYTITLE:Languages}}{{#set:Ativo=t}} | {{DISPLAYTITLE:Languages}}{{#set:Ativo=t}} | ||

{{#set:Data cadastro=2008-07-07}} | {{#set:Data cadastro=2008-07-07}} | ||

| − | </noinclude | + | </noinclude> |

Latest revision as of 15:19, 23 October 2019

Languages

More than 160 languages and dialects are spoken by the Indigenous peoples in Brazil today. They are part of the near 7,000 languages spoken today in the world (SIL International, 2009). Before the arrival of the Portuguese, however, only in Brazil that number was probably close to 1,000.

In the process of colonization of Brazil, the Tupinambá language, the most widely spoken along the coast, was adopted by many colonists and missionaries, taught to Indians grouped in the missions and recognized as Língua Geral. Today, many words of Tupi origin are part of the vocabulary of Brazilians.

Just as the Tupi languages have influenced the Portuguese spoken in Brazil, contact among peoples ensures that Indigenous tongues do not exist in isolation and change constantly. In addition to mutual influences, languages have among themselves common origins. They are part of linguistic families, which in turn can be part of a larger division, the linguistic branch. And just as languages are not isolated, neither are their speakers. In Brazil there are many Indigenous peoples and individuals who can speak and/or understand more than one language; and it is not uncommon to find villages where several tongues are spoken.

Among such diversity, however, only 25 peoples count more than 5,000 speakers of indigenous languages: Apurinã, Ashaninka, Baniwa, Baré, Chiquitano, Guajajara, Guarani [Guarani Ñandeva / Guarani Kaiowá / Guarani Mbya], Galibi do Oiapoque, Ingarikó, Kaxinawá, Kubeo, Kulina, Kaingang, Kayapó, Makuxi, Munduruku, Sateré-Mawé, Taurepang, Terena, Ticuna, Timbira, Tukano, Wapixana, Xavante, Yanomami, Ye'kuana.

Getting to know this vast repertoire has been a challenge to linguists. To keep it alive and well has been the goal of many projects of Indigenous school education.

In order to know which languages are spoken by each one of present-day Brazil’s 227 Indigenous peoples, access General table.

Trunks and branches

Among the approximately 160 Indian languages spoken in Brazil today, some have more similarities with each other than with others, which reveals common origins and diversification processes that took place over the years.

Experts on the knowledge of languages (linguists) express the similarities and differences among them through the idea of linguistic branches and families. Branches mean languages whose common origins are very old, and the similarities among them are very subtle. Among the languages of the same family, on the other hand, the similarities are greater, which is the result of a separation that took place not so long ago. See the example of the Portuguese language:

In the universe of Indigenous tongues in Brazil, there are two large branches - Tupi and Macro-Jê - and 19 linguistic families that do not have enough similarities to be grouped into branches. There are also families with a single tongue, sometimes called ‘isolated languages’, because they have no similarity with any other known language.

Very few Indigenous tongues have been studied in detail in Brazil. For that reason, the knowledge that exists about them is constantly revised.

Get to know the Brazilian Indigenous tongues, grouped in families and branches, according to the classification made by Professor Ayron Dall’Igna Rodrigues. It is a revision especially made for ISA in September of 1997 of the information published in his book Línguas brasileiras – para o conhecimento das línguas indígenas (São Paulo, Edições Loyola, 1986, 134 pages).

Source abel about Portuguese language: Raquel F. A. Teixeira - "As línguas indígenas no Brasil" . In: A temática indígena na escola - novos subsídios para professores de 1º e 2º graus, Brasília: MEC/ Mari/ Unesco, organized by Aracy Lopes da Silva and Luís Donisete Benzi Grupioni).

Tupi branch

Famílias linguísticas do tronco Tupi.

Famílias linguísticas do tronco Tupi.

Macro-Jê branch

Famílias linguísticas do tronco Macro-Jê

Famílias linguísticas do tronco Macro-Jê

Other families

Outras famílias linguísticas

Outras famílias linguísticas

Multilinguism

Text adapted from RODRIGUES, Aryon Dall´Igna – Línguas brasileiras: para o conhecimento das línguas indígenas. Edições Loyola, São Paulo, 1986.

Indigenous peoples in Brazil have always been used to situations of multilinguism. That means that the number of languages spoken by an individual can vary. There are those who speak and understand more than one language and those who can understand several but are able to speak just one or a few of them.

Thus it is not rare to find Indigenous societies or individuals in situations of bi-linguism, tri-linguism or even multi-linguism.

In the same village, it is possible to run into individuals who speak only the Indigenous tongue, others who speak just Portuguese and others still who are bi-lingual or multi-lingual. In general, linguistic differences are not a hindrance for Indigenous peoples to relate with each other and marry among them, exchange objects, participate in ceremonies and attend class together. A good example of that can be seen among the Indigenous peoples of the Tukano linguistic family settled along the Uaupés River, one of the rivers that form the Negro River, on both sides of the border between Colombia and Brazil.

Among these people of the Negro River basin, men often speak between three and five languages, or even more – some of them speak eight or ten. In addition, languages are for them elements that constitute their personal identity. A man must, for example, speak the same language as his father, that is, share with him the same ‘linguistic group’. However, he has to marry a woman who speaks a different language, i.e., who belongs to a different ‘linguistic group’.

The Tukano are thus typically multi-lingual, be it as peoples be it as individuals. Their example demonstrate how human beings have the capability of learning in different ages and of mastering several languages, independently of the degree of difference among them, and keep them consciously distinct with simply a good social motivation for so doing.

The multilinguism of the Indians of the Uaupés region does not include just languages of the Tukano family. It involves also, in many cases, tongues of the Aruak and Maku families, as well as the Língua Geral Amazônica or Nheengatu, Portuguese and Spanish.

In contexts such as that, sometimes one of the languages becomes the most widespread means of communication (what experts call lingua franca) and is used by everyone, when together, in order to understand each other. For example, the Tukano language, which belongs to the Tukano family, has a privileged social position among the Eastern tongues of this family because it has become the general language, or lingua franca, of the Uaupés area, and is the vehicle of communication between speakers of different languages. It has superseded other tongues – completely, in the case of Arapaço, or almost completely, such as in the case of Tariana.

There are cases in which it is Portuguese that is used as lingua franca. In some areas of the Amazon Region, for example, there are situations in which different Indigenous peoples and the local population speak Nheengatu, the Amazonian General Language, when speaking among themselves.

General languages

When the Portuguese colonization of Brazil started, the language of the Tupinambá Indians (of the Tupi branch) was spoken in a large area along the Atlantic coast. Thus already in the beginning of the 16th Century Tupinambá was learned by the Portuguese, whom at the time were a minority among the Indigenous population. With time, the use of that language, called Língua Brasílica – Brasilica Language -, was intensified and eventually became so widespread that it was used by almost the entire population that was part of the Brazilian colonial system.

A large number of colonists came from Europe without women and ended up having children with Indian women, so the Língua Brasílica became the mother tongue of these offspring. In addition, the Jesuit missions incorporated that language as a tool for the catechism of the Indigenous populations. Father José de Anchieta – a major personality in the early History of Brazil – published in 1595 a grammar called Arte de Gramática da Língua mais usada na Costa do Brasil – The Art of Grammar of the Most Widely Spoken Language on the Coast of Brazil. The first catechism in Língua Brasílica was published in 1618. A 1621 manuscript contains the Jesuit dictionary Vocabulário na Língua Brasílica – Vocabulary in Língua Brasílica.

Around the second half of the 17th Century, Língua Brasílica, already considerably altered by its current usage by mission Indians and non-Indians, became known as Língua Geral – General Language. But there existed, in reality, two Línguas Gerais in colonial Brazil: the Paulista (from São Paulo) and the Amazônica (Amazonian). It was the former that has left strong marks in the Brazilian popular vocabulary still in use today (names of objects, places, animals, foods etc.), so much so that many people imagine that ‘the language of the Indians was (only) Tupi’.

Paulista General Language

The Paulista General Language had its roots on the language of the Tupi Indians of São Vicente and of the Upper Tietê River, which differed somewhat from the language spoken by the Tupinambá. In the 17th Century, it was the language spoken by the explorers of the interior of the continent, known as bandeirantes. Through them the Paulista General Langauge penetrated areas in which the Tupi-Guarani Indians had never been to, thus influencing the daily language of a great many Brazilians.

Amazonian General Language

Rooted on the language spoken by the Tupinambá Indians, this second General Language developed at first in Maranhão and Pará in the 17th and 18th centuries. Until the 19th Century, it was the language used for catechism and for Portuguese and Luso-Brazilian social and political actions. Since the end of the 19th Century the Amazonian Língua Geral is also known as Nheengatu (ie’engatú = ‘ good language’).

In spite of the many changes it has suffered, Nheengatu continues to be spoken today, especially on the Negro River basin (Uaupés and Içana rivers). Besides being the mother tongue of the local population, it still maintains the character of language of communication between Indians and non-Indians, and between Indians of different languages. It is also a tool for the ethnic assertion of peoples whose languages have been lost, such as the Baré, the Arapaço and others.

School and writing

Prior to the establishment of systematic contact with non-Indians, the languages of the Indigenous peoples who live in Brazil were not written. With the development of projects of school education conceived for Indians, this has changed. This is a long story, which raises questions that ought to be thought upon and discussed.

A bit of history

The history of Indigenous school education shows that, in general, schooling had always had the goal of integrating the Indigenous populations into the greater society. Indian tongues were seen as the biggest obstacle for such integration. Thus the function of the school was to teach Indians student how to speak, read and write in Portuguese.

Only recently some schools have started to use Indigenous languages in alphabetization, when the difficulties of teaching students how to read and write in a language they are not familiar with, such as Portuguese, became clear.

Even in such cases, however, as soon as the students learned how to read and write, the Indigenous language was no longer used in the classroom, since the mastering of Portuguese was the main objective. So it is clear that, given that situation, school has contributed for the weakening, depreciation and, as a result, the disappearance of Indigenous tongues.

Indigenous languages at school

On the other hand, school can also be an element capable of encouraging and favoring the permanence or revival of Indigenous languages.

Inclusion of an Indigenous tongue in the curricular grid attributes to it the status of a full language and equals it, at least in terms of education, to the Portuguese language, a right mentioned in the Brazilian Constitution.

It is clear that the effort made at school for linguistic permanence and revival has limitations, because no institution alone can define the fate of a language. Just as schooling was not the sole culprit for the weakening and eventual loss of Indigenous tongues, it does not have the power of, alone, keep them strong and alive.

In order for that to happen it is necessary that the entire Indigenous community – and not only the teachers – wish to keep its traditional language in use. Thus schooling is an important but limited instrument: it can only contribute for the survival or disappearance of those tongues.

The Portuguese language at school

Mastering the Portuguese language at school is one of the tools that Indigenous societies have for interpreting and understanding the legal bases that conform life in Brazil, especially those that refer to the rights of Indigenous peoples.

All documents that regulate life within Brazilian society are written in Portuguese: laws – especially the Constitution -, regulations, personal documents, contracts, titles, registers and statutes. Indian are Brazilian citizens, and as such have the right to be familiar with these documents in order to interfere, whenever necessary, in any sphere of the country’s social and political life.

For the Indigenous peoples that live in Brazil, the Portuguese language can be an instrument for the defense of their legal, economic and political rights; a means to expand their own knowledge and humankind’s; a recourse for them to be recognized and respected nationally and internationally in their diversity; and an important channel for relating with each other and taking common political stances.

The introduction of writing

If oral language, in its various manifestations, is part of daily life in practically every human society, the same cannot be said regarding written language, since the activities of reading and writing can normally be performed only by people who were able to go to school and while there found favorable conditions to realize how important the social functions of those activities are.

Thus to struggle for the creation of Indigenous schools means, among other things, struggling for the right of the Indians to read and write in the Portuguese language, so as to make it possible to them to relate in equal conditions with the surrounding society.

Writing has many practical uses: in their daily lives, literate people elaborate lists for commercial exchanges, correspond with each other etc. Writing is also generally used to register the history, the literature, the religious beliefs, and the knowledge of a people. It is, also, an important space for the debate of controversial subjects. In today’s Brazil, for example, there are many texts that discuss topics such as ecology, the right of access to land, the social role of women, the rights of minorities, the quality of the education being offered, and so on.

School cannot aim at just teaching students how to read and write: it ought to give them conditions for them to learn how to write texts that are adequate to their intentions and to the contexts in which they will be read and used.

The benefits Indigenous peoples can obtain from learning how to read and write in Portuguese are thus very clear: the defense of their citizenship rights and the possibility of exercising them, and the access to the knowledge of other societies.

But writing Indigenous languages, on the other hand, is a complex question, one that must be pondered and whose implications must be discussed.

The functions of writing Indigenous tongues are not always so transparent, and there are Indigenous societies that do not wish to write their traditional languages. In general, this attitude becomes clear in the very beginning of the process of school education: the urge and the need to learn how to read and write in Portuguese is clear, whereas writing in Indigenous languages is not seen as so necessary. Experience shows that, with time, this perception can change and the use of writing in Indigenous languages may make sense and even be desirable.

One argument against the written usage of Indigenous languages is the fact that the introduction of such practice may result in the imposition of the Western way of life, which may cause the abandonment of oral tradition and lead to the appearance of inequalities within society such as, for example, the difference between literate and illiterate individuals.

But a strong argument for the introduction of written usage of Indigenous languages is that to limit those tongues to exclusively oral uses means to keep them in a situation of no prestige and of low practical applications, thus reducing their chances of survival in contemporary situations. And writing them also means that those languages will be resisting the ‘invasions’ made by Portuguese. In fact, they will themselves be invading the realm of a major language and conquering one of its most important territories.

[Text condensed and adapted from the document Referencial curricular nacional para as escolas indígenas, Brasília: MEC, 1998]

See also