Tenharim

- Self-denomination

- Kagwahiva

- Where they are How many

- AM 828 (Siasi/Sesai, 2014)

- Linguistic family

- Tupi-Guarani

Tenharim is the name by which are known three indigenous groups who live today in the mid Madeira River, in the Southern portion of the State of Amazonas, that belong to a wider set of peoples that call themselves Kagwahiva. In addition to the same self-denomination, the Kagwahiva peoples speak the same language, which belongs to the Tupi-Guarani family, and organize themselves in a similar system of matrimonial halves identified bird names. Of the three Tenharim groups, the one on the Sepoti River has its recent origin traced back to that of the Marmelos River; the one of the Igarapé (small Amazon waterway) Preto does not have a known common origin with the others, but has been an old ally of them.

The Tenharim within the Kagwahiva realm

In addition to the Tenharim, there exist other groups with a similar social organization. They all use the self-denomination Kagwahiva. For the Tenharim, the word Kagwahiva means “we”, “us”. Thus were these groups registered in historical documentation, but because of different spellings there has been much controversy regarding their name and range: Cavahiba, Cabaiba, Cabahiba, Kawahib, Kagwahív, among others.

Today there are few remnants of these Kagwahiva groups left: the Tenharim of the Marmelos River, the Tenharim of the Igarapé (small Amazon waterway) Preto and the Tenharim of the Sepoti River, in addition to the Parintintin and the Jiahui. They all still live in the Southern part of the State of Amazonas. Besides those groups, the Uru-eu-wau-wau, Amondawa, Karipuna and Juma are also considered Kagwahiva. The first three live in the region of the Upper Madeira, in the State of Rondônia, and the last in the region of the Purus River, also in the State of Amazonas.

The Tenharim groups live in the region anthropologists call Madeira-Tapajós (after the two major rivers that cut through it), each of them located in a different area that is geographically identified: Marmelos River, Sepoti River and Igarapé Preto. The Marmelos River and the Igarapé Preto groups have held an alliance that predates contact with ‘whites’, which was made in the mid-20th Century. The group of the Sepoti River was formed in the 1940s, when two women of the Marmelos married regionals and moved to a tributary downriver. Although the system is patrilineal and the Sepoti individuals descend from two regionals, the identity they assumed is the Tenharim’s.

The Tenharim are all bilingual. However, on the Igarapé Preto and on the Sepoti River, the indigenous language has been almost lost and now is being revived. Among the Tenharim of the Marmelos River, the native tongue is spoken within the group and Portuguese in the relations with the outside.

The Tenharim of the Marmelos River

This group lives on the Marmelos River, a tributary of the Madeira. Its village is cut in half by the BR-230, the Transamazônica (Transamazon) Highway. The road is the most important means of transportation for many of the items that these Tenharim produce, such as brazil nuts, copaiba (copal tree) and manioc flour, as well as for the manufactured goods, like salt, oil and soap, they need. Before moving to the highway, the group used to live in a village on the upper Marmelos River. In this area also used to live a merchant who intermediated the relations between the Tenharim and the regional population since the 1950s, and who influenced the group’s decision to move to the vicinity of the Transamazon Highway.

The Tenharim themselves consider their current population dense, but in the early 1970s the group was reduced in consequence of the transference of their village. There are reports that many Indians died at that time from diseases such as influenza and malaria. In 1994, the Tenharim numbered 301 individuals, of which 58% were 15-years old or less.

The Tenharim of the Igarapé Preto

The Tenharim of the Igarapé Preto live today in a village on a transition area between the wooded hills of Southern Amazonia and the cerrado (the Brazilian savanna). They numbered 43 individuals in 1997. They live on fishing and hunting, on gathering brazil nuts and on the sale of surplus of their production of manioc flour. Their search for increasing self-confidence and their effort to adopt traditional forms of organization that had been abandoned as a result of contact, especially with mining, is evident.

For a long time since the 1940s the Tenharim of the Igarapé Preto lived scattered through the region gathering rubber. They incorporated the system called aviamento, in which a merchant advances items needed by river dwellers and is paid later with forest products, and worked in seringais (rubber plantations). In the 1960s, the area was invaded by garimpeiros (miners) searching for tin ore, which was discovered around 1953 in the State of Rondônia and in the South portion of the State of Amazonas. New deposits and easier access thanks to the opening of the BR-364 (Cuiabá - Porto Velho Highway) and the BR-230 (Transamazon Highway) around the end of the 1960s and the beginning of the 1970s opened up the region for more garimpeiros, who mined the deposits manually. The Tenharim tell that it became impossible to fish and to hunt, because groups of garimpeiros were everywhere. Later the mining company Empresa de Mineração Paranapanema came to the area, followed by the Mineração Brasileira Estanho Ltda. (Mibrel). When the deposits of tin ore were exhausted the companies left, leaving behind a trail of destruction and an abandoned city.

The present village is built near the left bank of the Igarapé Preto, about one kilometer from the old headquarters of the mining company. It was built by the Mibrel as part of the payment for the exploration of the Indian area’s subsoil.

The Tenharim of the Sepoti River

In 1998 the Tenharim of the Sepoti River numbered 65 individuals, most of them under 19-years old. The area the group demands is being identified, and is divided in two: Estirão Grande, where the present village is located, and Sepoti, where the group carries out its productive activities and is currently building a new village.

The Tenharim of the Sepoti River do not differ substantially from the groups of the Marmelos and of the Igarapé Preto. On an economic standpoint, they are involved in the regional trade system with the regatões (merchants who ply the rivers of the Amazon Region), exchanging natural items they produce for manufactured goods they need. Although they do not perform their traditional celebrations on the Sepoti, they are perfectly in tune with the Kagwahiva traditions, establishing intermarriages and participating in the socio-cultural life of the village on the Marmelos River.

Population

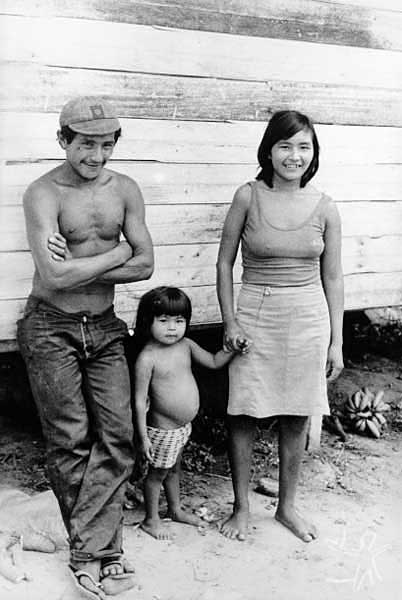

The Tenharim numbered in 1999 a total of 409 individuals living in three different Indigenous Lands, total which in 2006 rose to 699 people. In spite of considering themselves autonomous groups, they keep close relations with each other, which result, through marriage, in an intense movement of men and women between the three areas.

History of contact

The earliest references to the Kagwahiva groups place them, around 1750, on the region of the upper Juruena River, next to the Apiaká Indians. The region was virtually ignored by the expansion frontier, but later was traversed by mining expeditions, which moved North from Cuiabá in search for new gold mines. This fact, as well as a war against the Munduruku Indians, has been described as the reason for the migration of the Kagwahiva from that region to the banks of the Madeira River.

In 1817, already established on the river, the Kagwahiva are mentioned for the first time by the name of Parintintin, perhaps given by their enemies Munduruku. In 1850, the denominations Kagwahiva and Parintintin are mentioned simultaneously; after that, the name Kagwahiva disappear and those peoples are designated as Parintintin. After their "pacification" by Nimuendajú in 1922, it was understood that Kagwahiva is the self-denomination of the Parintintin, and that this name applied to just one of these Kagwahiva peoples.

On the Madeira River region, the Kagwahiva groups allowed the approach of the Brazilian society only after an intense war that lasted some 70 years, between the mid-19th Century and the 1920s, and that ended only with the actions of the Serviço de Proteção aos Índios (SPI) - Funai’s predecessor as the Brazilian government’s indigenist organ - and after rubber gatherers had established themselves in the area. Curt Nimuendajú was the main agent for this: hired by the SPI, he organized expeditions and moved to the Kagwahiva territory; due to the SPI’s lack of funds, however, he abandoned his project five months later and left in his place several of his aides, who carried his mission on.

It seems that at that time the diversity of the Kagwahiva peoples in this region was unknown, since all of them were considered Parintintin. The denomination Kagwahiva, however, is older, and references to it in several different places seem to indicate movements within a vast extension of the Madeira-Tapajós area.

The Kagwahiva, known after 1817 as Parintintin, were divided into small local groups, with a determined territory and occupying a vast region between the Madeira and the Tapajós rivers. They shifted from alliance to war and back with each other, but recognized themselves as a single society. It is probable that each one of those local groups organized itself around a domestic group, and had the name of its leader or its location (such as rivers, mountain ranges etc). Factionalism is a characteristic of these peoples, and in consequence alliances were unstable and new groups were constantly being formed. Oral accounts reinforce territoriality, describing their distribution in the region, carried out by Nhaparundi, a Tenharim ancestor. They also recall that, in the earliest times of contact, the groups united in order to avoid contact with non-Indians. In a way, it is impossible to register with precision the formation of the Kagwahiva peoples in the region, but the reports demonstrate, and the documentation confirms, that they occupied the region between the Madeira and the Tapajós rivers.

The stories told by the Tenharim of the Igarapé Preto denote a very old occupation of the mountainous region where they currently live. Their long migrations always have as reference the mountain ranges and the cerrado that surround the Igarapé Preto. The mountain ranges are part of the Kagwahiva cosmological universe as well. The mythic hero Mbahira lives in them; he has several pets and many attributes related to the rocks. All the mountain ranges of the Igarapé Preto region are regarded as the home of Mbahira and, in such places, it is possible to find many things that belong to this hero (flowers, feces, animals, flour).

The Kagwahiva narrate their past feats by chanting. All those chants are followed, in the end, by a sentence that identifies the group that experienced it. Among the Tenharim of the Igarapé Preto, in the sentence "Iu, Iu, Tenondehu, Yvytyruhu", which follows the end of their chants, the word Yvytyruhu designates the mountainous region where the group lives. The chants of the Tenharim of the Marmelos River, in turn, refer to the river, which they define as Ytyngyhu.

The Tenharim of the Sepoti River are descendants of Tenharim who, in the 1940s, left a village that used to exist on the mid Marmelos River. These individuals - actually two non-Indian men who married two Tenharim women - decided to settle on the Sepoti River to work in the extrativist activity, gathering brazil nuts, sorva (an Amazon fruit) and rubber.

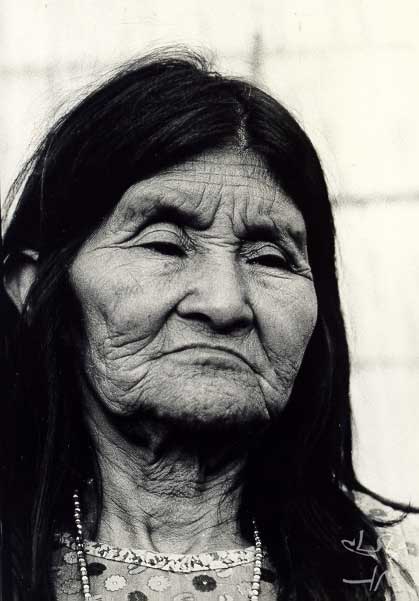

Its population has grown, thanks to marriages within the original group, but these Indians continued to live in the region of the Sepoti River. The two men who gave origin to the group back in the 1940s are dead, but their wives are still living; the rest of the group is composed of their children and grandchildren and their husbands or wives.

Social organization

The Tenharim’s social organization, as of the other Kagwahiva, has a particularity regarding the other Tupi-Guarani peoples: a complex system of exogamic halves that receive names of birds. These halves are the Mutum-Nanguera and the Kwandu-Tarave. In the first, to mutum (curassow) is associated the word Nanguera, which does not refer to a bird, meaning, according to the Tenharim, something from the past. In the second, to Kwandu (harpy eagle) is associated Tarave (a kind of macaw).

Every individual belongs to his/her father’s half, because it is a patrilineal system. And because it is exogamic, he/she can only marry someone that belongs to the opposite half. That divides society in half, in two large groups that intermarry with each other. Marriage within the same half is allowed only when the groom lives far away. In this case, things take place as if geographic distance caused a genealogical distance, transforming the forbidden marriage into an acceptable union.

The rule of post-marital residence among the Tenharim is patrilocal, and there is a period of ‘bride-service’ during which the son-in-law owes his father-in-law obligations because of the marriage. The time period for that varies according to the prestige of the men involved in the relationship. Powerful fathers-in-law head domestic groups that work together permanently, but in the cases in which the father-in-law’s political power is non-existent the sons-in-law move close to their parents after approximately five years.

The strategy for the constitution of the domestic groups involves the retention of the sons and the co-optation of sons-in-law through the institution of the bride-service. The domestic groups may group together in larger units, the residential segments, which make up the political factions that dispute among each other within the society.

Economic activities

The beginning of the dry season, which takes place around June in Southern Amazonas, is marked by the clearing of the forest and the planting of the roças (planting fields). On the Transamazon Highway (where the Tenharim of the Marmelos River live), this time of the year many families leave the village and move temporarily to their sítios (plots), preparing the fields and putting some distance between themselves and the others. Some have actually opted to live permanently in their sítios, and now keep a residence in the village only for occasional visits. In the sítios there can be seen the introduction of new plants, such as watermelon and, in some cases, cattle raising as well. Despite the low value in the market, manioc flour continues to be the most important product the Tenharim produce for sale.

On the Transamazon Highway and on the Igarapé Preto, manioc flour’s surpluses are exchanged in the village for manufactured products. This exchange is made with merchants who come from town bringing with them items that had been previously ordered. As a general rule, these merchants overvalue their manufactured goods and undervalue the Tenharim products. In addition to manioc flour, they also buy brazil nuts and copal oil. They use a truck that belong to the Tenharim or else another that belongs to the city government, which passes once a week on the Transamazon Highway, taking back and forth people who live along the road. On the Sepoti, the Indians trade with the regatões, who come to the village on boats stocked with manufactured goods for exchange.

Besides agriculture, the Tenharim live on hunting, fishing and gathering of forest products. Some domestic groups produce crafts such as bows, arrows, headdresses, necklaces, bracelets and rings, which are sold in Porto Velho and on occasional trips.

Symbolic universe

The village on the Marmelos River is the reference for all the Tenharim groups. It is in it that the traditional celebrations take place, congregating the majority of the Kagwahiva groups. Only the Kagwahiva of the region of the Upper Machado River (Amondawa, Uru-eu-wau-wau, Juma and Karipuna) do not take part in them. However, more recently, with the articulation of the regional indigenous movement, a tendency for these rituals to congregate all Kagwahiva groups can be noticed. The most important of those celebrations is called Mboatava. It is held between July and August and has a close relationship with the domestic groups. An individual assumes the organization of the celebration and calls the best hunters and fishermen to go on expeditions. While the hunters are away, much mandio’y flour is produced by those who are part of the organizer’s domestic group. The chief gives permission to have green bananas taken from his roças and be placed near his house, in addition to distributing many products given by the Funai, which are stored under his responsibility. Besides banana, which will be ripe by the time the celebration starts, and the flour, the Tenharim make expeditions for gathering brazil nuts, used in the preparation of the celebration’s main dish, tapir meat cooked on brazil nut milk.

Several groups of hunters, called by the celebration organizer, leave in different directions to hunt and fish (usually they go by boat). Everything they get is moqueado (cooked on low fire). After a few days the expeditions meet at a pre-determined place near the village and triumphantly return to it. When the hunters appear in the distance, the men who remained in the village have already painted their bodies; they shout and shoot in the air to welcome the newcomers. The organizer then begins to sing and play the flute, walking around the houses. The animals that were hunted are cooked and he distributes among the villagers some of the fish, along with the mandio’y flour. The brazil nuts are crushed, then cooked with the tapir meat and finally served with flour in the form of a mush.

At the same time, the men begin to dance on the patio of the domestic group to which the organizer belongs. They dance in circles, adorned accordingly with headdresses and skirt, holding long bamboo flutes called Yreru, which they point to the center, while marking the rhythm stomping their right foot. Later the women enter the circle of dancers, under the arm of their husbands.

Note on the sources

About the history of the mid course of the Madeira River, where the Tenharim and the other Kagwahiva in general live, there are two vast studies made by Vitor Hugo (1959), under a missionary point of view, and by Miguel Menéndez (1981/82; 1984/85). More specifically about the Kagwahiva, there are the report by Curt Nimuendajú (1924) and a text by the same author published in the Handbook of South American Indians ([1948]1963). The Tenharim of the Marmelos River were reference in the studies made by Menéndez (1989) and Peggion (1996a). They also appear in articles written by these same authors: Menéndez (1987) and Peggion (1995; 1996b).

The Tenharim of the Igarapé Preto are mentioned in a series of reports made at the Funai’s request to identify and assess the impact of mining activities in their Indigenous Lands (Maciel, 1987; Santos, 1989; Peggion, 1997), and in an article about the identification work (Peggion, 1998). The Tenharim areas of the Marmelos River and of the Igarapé Preto are dealt with together in Mariz, 1984; Menéndez, 1985a; 1985b; and Valadão, 1987. As for the Tenharim of the Sepoti River, Heringer and Lange (1981) registered their visit to the region where they live, and the identification report of their Indigenous Land is currently under analysis (Peggion, 1998).

Sources of information

- COSTA, Plácido. Manejo dos recursos naturais e territorialidade no grupo Tenharim do Igarapé Preto. In: KASBURG, Carola; GRAMKOW, Marcia Maria (Orgs.). Demarcando terras indígenas : experiências e desafios de um projeto de parceria. Brasília : Funai/PPTAL/GTZ, 1999. p. 219-32.

- HUGO, Vitor. Desbravadores. 2 v. Humaitá : Missão Salesiana de Humaitá, 1959.

- MENENDEZ, Miguel Angel. Contribuição ao estudo das relações tribais na Área Tapajós-Madeira. Rev. de Antropologia, São Paulo : USP, v. 27/28, p. 271-6, 1984/1985.

- --------. Uma contribuição para a etno-história da área Tapajós-Madeira. Rev. do Museu Paulista, São Paulo : Museu Paulista, v. 28, p. 289-388, 1981/1982.

- --------. Os Kawahiwa : uma contribuição para o estudo dos Tupi centrais. São Paulo : USP, 1989. (Tese de Doutorado)

- --------. A presença do branco na mitologia Kawahiwa : história e identidade de um povo Tupi. Studi e Materiali di Storia delle Religioni, Roma : Japadre Ed., v. 11, n. 1, n.s., p. 75-97, 1987.

- --------. Os Tenharim : um grupo Tupi a beira da Transamazônica. Boletim. do GEI Kurumin, Araraquara : Unesp, v. 3, n. 25, p. 10-3, fev. 1984.

- NIMUENDAJÚ, Curt. The Cawahib, Parintintin and their neighbors. In: STEWARD, J. (Ed.). Handbook of South American Indians. v. 3. New York : Cooper Square Publishers, 1963. p. 283-97.

- --------. Os índios Parintintin do rio Madeira. Journal de la Société des Américanistes, Paris : Société des Américanistes, v. 16, p. 201-78, 1924.

- PAES, Silvia Regina. Mito e cultura material. Terra Indígena, Araraquara : Centro de Estudos Indígenas, v. 12, n. 76, p. 3-42, jul./set. 1995.

- PEGGION, Edmundo Antônio. Estratégias matrimoniais e sociabilidade em um grupo Tupi : os Tenharim do Amazonas. In: SILVA, Aracy Lopes da; GRUPIONI, Luís Donisete Benzi (Orgs.). A temática indígena na escola : novos subsídios para professores de 1o. e 2o. graus. Brasília : MEC/ Unesco ; São Paulo : Mari, 1995. p. 460-1.

- --------. Forma e função : uma etnografia do sistema de parentesco Tenharim (Kagwahiv, AM). Campinas : Unicamp, 1996. (Dissertação de Mestrado)

- --------. Os procedimentos na identificação de terras indígenas : relato de uma experiência. Boletim da ABA, Campinas : Unicamp, n. 29, p. 12-4, 1998.

- --------. Os Tenharim do rio Marmelos querem rever demarcação. In: RICARDO, Carlos Alberto (Ed.). Povos Indígenas no Brasil : 1991/1995. São Paulo : Instituto Socioambiental, 1996. p. 373-4.