Jiahui

- Self-denomination

- Kagwaniwa

- Where they are How many

- AM 115 (Siasi/Sesai, 2014)

- Linguistic family

- Tupi-Guarani

The Jiahui are a people of the Tupi-Guarani language family, a subgroup of the Kagwahiva, who live in the region of the middle Madeira River, in the south of the State of Amazonas. Historical circumstances have caused the near extinction of the group. Their traditional lands have been occupied by ranchers and the Jiahui have come to live together with the Tenharim or in nearby cities. In the midst of conflicts, the process of regaining indigenous territory was begun in 1998, in which the Jiahui have sought to reorganize themselves in order to guarantee their physical and cultural survival.

Name and language

The Jiahui, people of the Tupi-Guarani language family, are a subgroup of the Kagwahiva. Presently, the surviving Kagwahiva are the following: Jiahui, Tenharim (of the Marmelos River, of the Preto stream and of the Sepoti), Parintintin, Juma, Uru-eu-wau-wau, Amondawa, Karipuna, besides some possibly isolated groups.

Until the 1920s, all the Kagwahiva peoples were referred to as Parintintin. Ever since they were recognized as a specific ethnic group, the Jiahui have received many denominations: Odjahub, Diahói, Odiarhúebe, Odiahub, Odiahuebs, Odiahuebe, Diarrús, Odiahuve, Odyahuibé, Diahus, Diarrhus, Odayahuibe, Diarrói, Odiahueba, Odyahuibó, Odiahúbes, Diarroi, Diahub, Jahoi, Odiahuibe, jahui, Diaói, Odiabuibé and Diarru. The present spelling – Jiahui – is of the Indians’ own choosing.

Territory

The first reference to the Kagwahiva appears in 1750, in the region of the upper Juruena River, next to the Apiaká. Soon after, this area was swept by the mining front which, from Cuiabá, advanced to the North in search of new goldmines, which could have caused the beginning of Kagwahiva migratory processes (Menéndez, 1989:38). Besides that, the war with the Munduruku has also been indicated as a cause of their migrations.

The Jiahui are part of a group of peoples who occupied the middle Madeira River, in the south of the State of Amazonas, after migrating from the upper Tapajós, pursued by their traditional enemies, the Munduruku, sometime after 1750.

In the 1970s, they were driven out of their traditional territory and the group practically broke up due to conflicts with neighboring indigenous groups, as well as the setting up of ranches and illegal extraction of lumber. The few remaining jiahui allied themselves with the Tenharim and went to live in a village of these people near the Trans-Amazon highway. They married with them and had children, but they were never totally absorbed by the Tenharim.

As a result of internal pressures in the village, the Jiahui moved to the eastern limits of Tenharim land and from there they began to make incursions into their traditional territory, now occupied by ranches with land titles issued by the Incra (National Institute for Colonization and Agrarian Reform). These incursions, which initially were for the purpose of gathering cashews, became more frequent, for hunting and gathering until, in 1999, they decided to reoccupy their traditional territory by moving onto the ranchlands, building a village and clearing gardens.

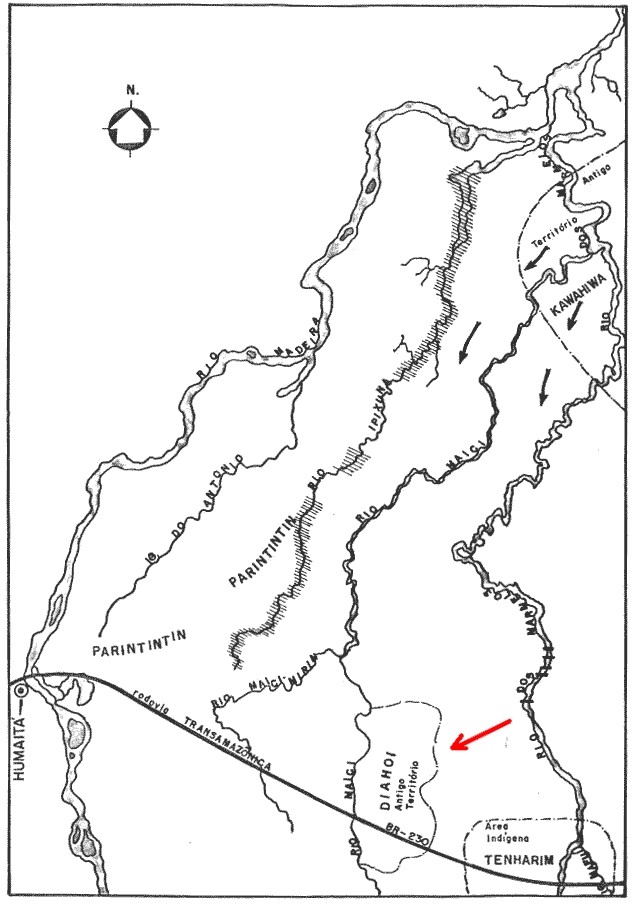

As a way of claiming their right over the land, the village they built was called Ju’í, which was the name of an ancient village located in the same direction, just more to the South, within the occupied territory. The present village is about 100 meters from the Trans-Amazon highway, and is also near the left bank of the Amazônia stream (tributary of the Marmelos River). The choice for making the village near the Trans-Amazon is due to the fact that it is by means of the highway that they can sell their products and it is also where they can get goods, have their sick taken care of, among other factors relevant to the indigenous populations of the region.

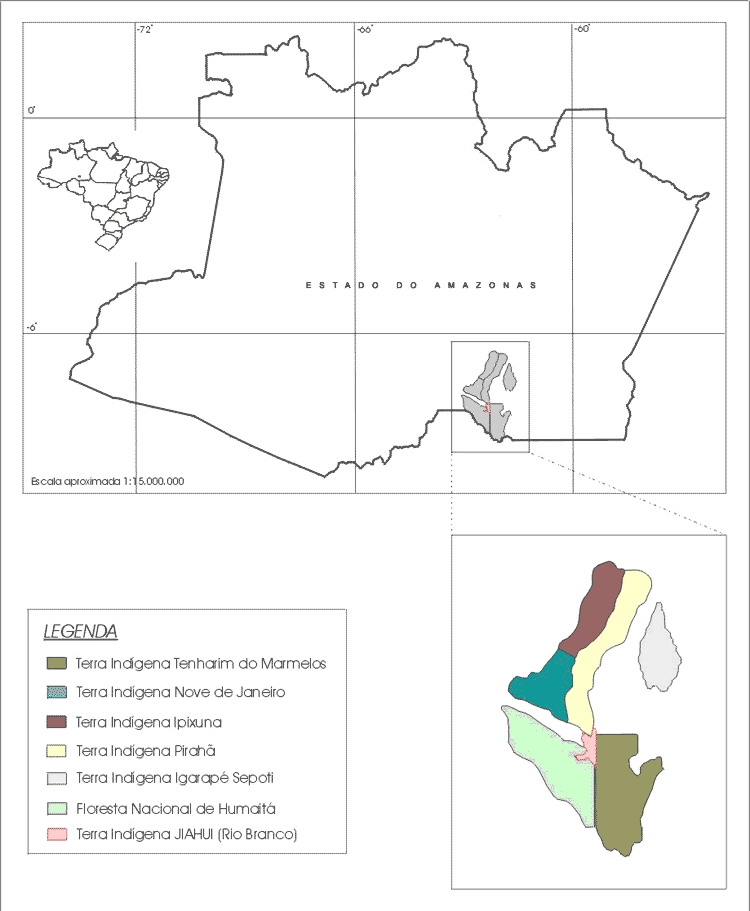

Having been declared an Indigenous Land and currently in the phase of demarcation, Jiahui Indigenous Land belongs to the municipality of Humaitá (AM) and had its land surface defined at approximately 47,600 hectares with a perimeter of 150,000 meters. The Indigenous Land borders on the Tenharim and Pirahã lands, the Humaitá National Forest and the lands of small farmers. In this way, there is practically no possibility that their lands will be invaded.

There are, however, conflicts resulting from the property titles conceded by the Incra inside the traditional territory of the Jiahui. These lots were small properties more or less around 100 hectares in size. With the passing of time, much land was abandoned and sold to neighbors and, thus, some few landholders have come to possess extensive properties.

The major conflict is with the rancher Eduardo Esteves Duarte, given that, besides the land itself, he disputes with the Indians the exploitation of an area of cashew trees, defined by the Jiahui as Tañoapina. During the season of cashew production, their encounters with Duarte’s employees, who also have gone in search of the product, were frequent and marked by conflicts. However, although the occupation of the lands was done with titles issued by the Incra, the place always belonged to the indigenous people.

Besides the non-Indian landholders, there is another question which involved the Jiahui Indigenous Land: part of it overlaps with the National Forest of Humaitá. On March 22nd, 1988, the then President of the Republic José Sarney published decree no. 95.859 defining the tracts of land called Boa Esperança and Pupunhas as being for the use of the Army, a total of 468,790 hectares, creating the Military Glebe of Humaitá. On March 19th, 1997, Fernando Henrique Cardoso revoked several clauses of this decree. On February 2nd, 1998, President Cardoso signed another decree (no. 2.485) creating the National Forest of Humaitá with the same land surface as the Military Glebe. This area is presently under the jurisdiction of the Ibama and is a Conservation Unit for exploitation with multiple use management of the renewable resources. Thus, the Federal Union itself ended up imposing overlapping limits in defining the Military Glebe and later the Humaitá National Forest on parts of the limits of the Indigenous Land.

History of contact

The Kagwahiva are mentioned for the first time in 1750, in the region of the upper Juruena River, next to the Apiaká. Soon after, this area was swept by the mining front which, from Cuiabá, advanced to the North in search of new goldmines, which could have caused the beginning of Kagwahiva migrations (Menéndez, 1989:38). Besides that, the war with the Munduruku has also been a cause of their migration from this region to the banks of the Madeira River (Nimuendajú, 1924:207-208). Yet, it is difficult to make any more categorical statements about this period, for the conditioning factors of this migration are much more complex and are related to an intertribal dynamic in the region.

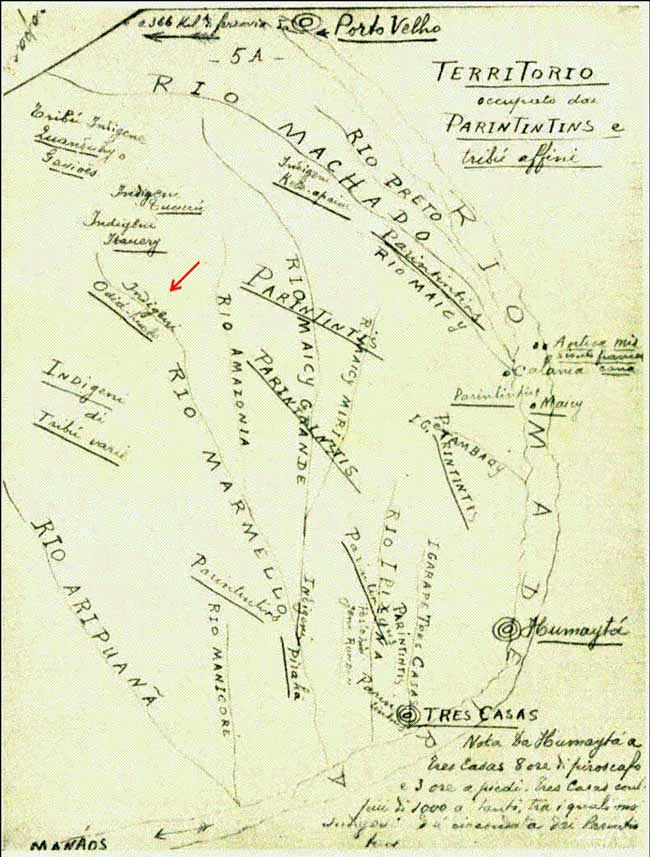

In 1817, the Kagwahiva are mentioned for the first time by the ethnonym Parintintin, a name given perhaps by the Mundurucu to their enemies. In 1850, Kagwahiva and Parintintin are mentioned at the same time, but after this the ethnonym Kagwahiva disappears from the literature and these people are then designated as Parintintin. After the “pacification” undertaken by Nimuendajú in 1922, it was possible to establish positively that Kagwahiva was the self-designation of the Parintintin and that the latter designation applied to only one of these peoples (see the Parintintin article).

In the region of the Madeira River, the approximation of the Kagwahiva groups to Brazilian society took place after an intense war, which lasted for nearly 70 years, between the middle of the 19th Century and the 1920s. This war only came to an end with the action of the SPI (Indian Protection Service) and after the definitive entry of rubber-gatherers in the region. Curt Nimuendajú was the principal agent in this approximation: hired by the SPI, he organized expeditions and established a camp inside the indigenous territory. Due to lack of resources from the SPI, Nimuendajú abandoned his project after only five months, leaving several assistants in his place.

According to Nimuendajú (1924:201-203), Parintintin (that is Kagwahiva) territory in the region of the Madeira River extended for nearly 22,000 square kilometers, delimited to the North and West by the Madeira; to the South by the Machado River and to the East by the Marmelos River, with its eastern branch the Rio Branco.

Nimuendajú reported (1924:203) that, between his first contacts with the Parintintin people until his departure, there was a population of 250 individuals. The group’s subsistence was based on an economy adapted to the tropical forest. They planted corn, manioc, sweet potato, urucum, cotton, banana, and papaya. They fished with bow and arrow and fish poison (timbó) and hunted especially tapirs, deer, and monkeys.

Shortly after the first contacts with the Parintintin, the SPI employees began to record the appearance of other Kagwahiva peoples in the region. The first group to be referred to as a matter of concern to this agency was the Jiahui. In an attempt to attract them to contact, José Garcia de Freitas and other assistants began the process of approximation and related their experiences in extensive reports. At first, the Indians were seen from a distance in the region of the headwaters of the Rio Branco, and later they were located in the region of the Amazonia stream, the location of their present village. Their intent in “pacifying” the Jiahui is explicit in many documents.

As far as the relations between the Parintintin and the Jiahui, the information gathered always came from the perspective of the Parintintin, since the Jiahui were still isolated:

According to information gathered among the Parintintins, by the head of the post of Maicy-mirim, the Odiarhúebe speak the same dialect and have almost the same customs as that tribe, there being nevertheless a high degree of hostility between these two deriving from their warrior disposition, which makes them spiteful enemies.

In contrast to the Parintintins, who usually cut their hair around the head, the Odiarhúebe keep theirs long and thick; but like the Parintintins, they also wear penis sheaths made with a tube of arumã leaves, in the form of a cylinder. Their akanitaras (headdresses) are made of japú and red macaw feathers and their arrows are made in the same way and have the same adornments as can be observed of the warrior weapons of the Parintintins.

The Parintintins, dominated by natural superstition, that assaults the spirit of nearly all the tribes, have an immense fetishist fear of these kin and enemies. They say that, incited by vengeance, the Odiarhúebe usually send great bats at night to them, which steal their hair, using it in witchcraft and in this way, every now and then, transmitting the worst evils to their malocas” (Lemos, 1925:20).

In the 1930s, the SPI intensified their activities in an attempt to attract the Jiahui to contact. To this end, expeditions were organized under the command of José Garcia de Freitas, who already knew the Kagwahiva through his work with the Parintintin. In his search, Garcia ended up coming upon the PAIN and not the Jiahui. After sequestring a woman and her children, Garcia asked the Parintintin who accompanied him to tell them of the SPI’s good intentions. The woman declared that her husband and the rest of her group would come back and kill all of them. Even so, Garcia decided to stay in the same place and on the next day he let the woman go with some presents, but kept her children. Some time later two painted warriors appeared, threatening everyone and asking which of them was the ipají [shaman]. After Garcia calmed the warriors down, he established a good relation among all of them. From his report, we can see that he was dealing with one of the Jiahui:

The language is exactly the same as the Parintintin, there being only a bit of difference in the dances and songs.

They call themselves PAIN, they are a group which separated from the Odiahub and live in constant struggle with them. Hardly a month had passed in which the Odiahub had unexpectedly killed four men and I had the opportunity to see one of them with an arrow wound in his right breast. They laughed, and took delight in the alliance that I offered them against their enemies.

The PAIN Indians were amazed that we had not been attacked by the Odiahub, saying that close to there were their war paths; that is to say that, if we had delayed a bit more, we would be attacked by them. I did not propose to establish friendship with their enemies, because I knew the hatred and thirst for vengeance that they had and the rancour they had for the victims; but I requested that they wait for us to attack the Odiahub.

It was a trick that I used to avoid any shock between the enemy groups” (Garcia de Freitas, 1930:06-07, my emphasis).

Nevertheless, when Garcia de Freitas returned to the place (which is reported in this same document of 1930), the confrontation between the Pain and Jiahui groups had already occured, and he was only able to find eight individuals. After several years had passed, the circumstances were different and the Jiahui were already suffering the consequences of contact, which included destructuring the traditional forms of social organization. Several groups, however, succeeded in remaining isolated. They stayed in the forest, establishing contact only with the cashew-gatherers who exploited traditional Jiahui territory, where there are stands of cashews. But in the 1970s, with the opening of the Trans-Amazon, which cut through their lands, it was no longer possible to maintain their isolation.

The opening of the road caused much commotion among the indigenous population, which heard the noises and tried to understand what was going on. The oral narratives from this period are truly astonishing and tell of a critical moment in the lives of the Jiahui. Tormented to one side by the Tenharim and on the other by the Paranapanema Company and its employees, the group watched at a distance the movement and machines that pushed ever further into the forest.

After various quick appearances, the Jiahui were surprised to see that among the Paranapanema workers, there were many Tenharim. One of them, Kari, from the Preto stream, was the one who went to the front to establish contact with the Jiahui. He called them, accompanied by a non-Indian worker, offering food and clothes. The approximation was gradual and tense. Borobé did not allow his children to put any of the food in their mouths, for he didn’t have the least confidence either in the workers or in the Tenharim. But contact intensified and the Jiahui came to live in the Tenharim village.

In the mid-1990s, with the population growth among both the Tenharim and the Jiahui, the situation of tension recurred in the relations between the two groups. It was at this time that the Jiahui began a process of re-occupying their lands.

Population

The Jiahui today total 17 people in the Ju’i village, besides various individuals located in other indigenous lands and in nearby places. Summing the population inhabiting the village of Ju’i with the individuals who live together with the Tenharim and in Humaitá and Porto Velho, we get a total approximate population of 50 individuals.

The moment that these people are living is very special. From a population which was considered extinct, they have begun to reorganize, they have re-occupied their traditional territory and they intend to recompose their fragments, seeking those who live in other villages and even in nearby urban centers. What is important is that, although they have gone through a period of dispersion, they have never totally lost contact. Many of them know how to locate their kin, even tracing their genealogical relations.

Presently three probable domestic groups are in formation. However, individuals undertake their economic activities collectively. When the results of a hunt are abundant, they are distributed amongst everyone. There are certain trails over which everyone goes to undertake economic activities. But, projecting to the future, very probably, different domestic groups will make their own ways within the territory.

Social organizanition

The Jiahui, as well as the Kagwahiva in general, are Tupi peoples, but they have one peculiarity in relation to the other Tupi-speaking groups, which is a complex systems of exogamic moieties that have the name of two birds: Mytu e Taravé (curassow and maracanã, a bird of the parrot family). This system defines marriage possibilities for, a man, when he is born, belong to the moiety of his father and can only marry into the opposite moiety.

This system divides the society into two large groups who marry amongst themselves. Marriage in the same moiety is only possible when the individual lives far away. In this case, everything happens as though geographical distance creates genealogical distance, transforming the prohibited marriage into a possible union.

Although depopulation has made the functioning of this system difficult in the case of the Jiahui, it continues operating, whether in internal marriages or in marriages with other Kagwahiva groups. It was in this way that several marriages occured with Jiahui and the Tenharim of the Marmelos River. Pressured and desparate, the remaining Jiahui were incorporated through marriage to the Tenharim in the 1970s. Today we have certain situations of marriages in the same moiety, but which don’t harm the system in any way since the genealogical distance between the groups permits such a fact.

Transit throughout the territory is a characteristic of the Kagwahiva, who were distributed in small local groups in a vast region between the Madeira and Tapajós rivers. They lived between conflict and alliance, but they recognized themselves as a single society. Each one of these local groups, which probably was organized around a domestic group, was known by the name of its leader or its location (rivers, hills, etc.). Factionalism is a characteristic of these peoples and consequently the unions were unstable and new groups were in constant formation. The political strategies tied to the residential question characterize their way of conceiving the occupation of the territory and group constitution. Oral histories reinforce the territoriality of the groups, for they tell of their distribution in the region by Nhaparundi, the Kagwahiva mythical ancestor, and also that, in the initial moments of contact, the groups united in order to flee from the non-Indians (Menéndez, 1987:86-87; 1989:80).

The factional characteristics of the Kagwahiva groups still cause internal disputes today, making new villages arise. These new villages, however, are formed in territorial space considered as belonging to these groups. Thus, according to the Jiahui, the Tenharim and the Parintintin are located in their traditional territories. According to the Jiahui and also the Tenharim, the present territory reoccupied by the Jiahui is effectively the place that they always inhabited.

Productive activities

In the area behind the village of Ju´i, the Jiahui have a garden with manioc, yams, papaya, among other produce. Around the village, hunting, gathering, and fishing trails lead out, which were made well before the construction of the present village. Hunting, fishing, and agriculture, in general, are done for the sustenance of the group. Gathering, on the other hand, is done from the point of view of the insertion of the group in the regional market.

Cashews are the central produce which occupies Jiahui time for a good part of the year. Recently, in the movement to return to their traditional territory, they have begun gathering again in the Tañoapina cashew stands and have also begun to gather other produce which is of interest to the regional market, such as açaí. This is produced and consumed in great quantities on Jiahui lands.

The hunting trails are the same as those used for other activities. Thus, when an individual goes out to hunt, he follows the same trails that lead to the cashew or açaí groves, for example. However, there are alternative trails called “hunting trails”. By way of these connections, large areas of the territory are covered in search of animals such as the taiaho (peccary), paca and cutia. The Trans-Amazon is also used like a hunting trail and occasionally the men go out on foot or bicycle in search of cotias, which are found with frequency.

A strictly male activity, hunting is one of the principal sources of protein for the community. Although it is not always possible, the objective of a hunter is always to bring down a large-sized animal. Nevertheless, the hunter does not avoid bringing down another small animal or birds that by chance may come across his path. The latter type of action is what happens in cases of occasional hunts.

Hunting may be done with firearms, bow and arrow, or even by means of traps set up in the forest. It can be done individually as well as in groups of two or three hunters. In any case, the successful hunt is always shared with the whole community. Whatever is left over is either grilled or salted.

Although it is not as central as hunting, fishing also has some importance, and is practiced as an activity that complements the food diet of the indigenous community. In contrast with hunting, fishing can be done by children and women in the waterways located nearby the village.

The species that are most valued are the tucunaré, surubim, tambaqui, jatuarana, matrinchã and piau. Techniques and instruments include lines, paternoster line, arrows, spears, the jyki’ywa (juqui, a kind of trap) and timbó fish poison. Line fishing is a common activity in which nylon line and hook are used to catch fish in lakes and pools, where the water is still. The paternoster line consists of putting several hooks on a line and tying the ends between small tree branches near the water. As the line stays fixed, this allows the individual who sets it up to do other activities. The arrow and spear are techniques of wide diffusion in the Amazon region and demand a great deal of dexterity on the part of the individual who manipulates these instruments. There are even other mechanisms of traditional Kagwahiva use, such as the making of a wooden fish, which is tied near the water surface in order to attract the fish. After the first fish is caught (with arrow or spear), this substitutes the wooden fish and the fishing continues. Another technique consists of making a small circle which, when stuck on a piece of dry kindling, will be utilized to beat on the surface of the water imitating the sound of fruits falling. The sound will attract the fish which will then be caught. The jyki’ywa (juqui) trap serves to capture large and small fish. It is made with inajá strips more or less in the form of a basket. When placed in the current the fish end up entering it in search of food and can’t get back out.

An activity which is greatly esteemed by the Jiahui and Kagwahiva in general, fishing with timbó is mostly used during the summer, when it is possible to find small pools of water that are left from streams whose water level has lowered. Timbó is a poisonous vine that, when beaten and thrashed, releases a toxic substance in the water paralyzing the fish. The native conception of this process demonstrates that a war is being waged between the timbó and the fish. Some fish win the battle, not succumbing to the effects of the poison. This is the case of the acará and the jeju. In order to be successful, it is necessary to converse with the vine, asking it to kill the fish.

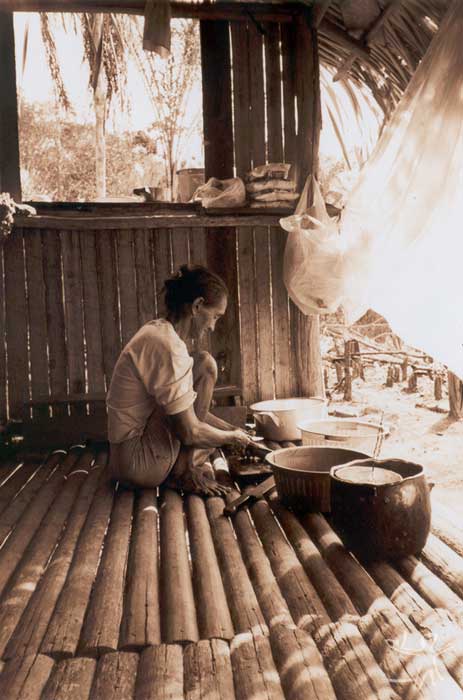

In the case of gathering, depending on the effort involved in the activity, men or women can do it, or even, in some cases, it is an activity that includes all members of family groups, that is, men, women, and children. As a product gathered for consumption, cashew is used in its natural state, mixed with typical plates such as beijú and tapioca, or as a seasoning for meats. As a market product, cashew has a price that varies with the harvest.

The Indians spend the day breaking cashews and either return to the village or stay near the cashew groves, sleeping in small shelters. Daily production is never greater than two tin cans of cashews per family group. In order to supply their needs during the harvest, the Jiahui prepare food provisions in the weeks before the harvest period. It could also happen that they promise the harvest ahead of time to some buyer, receiving from him manufactured products such as oil, salt, rice and coffee, among other things, which make up their so-called “grub”. In these cases, the group takes part in the economic system typical of Amazonia called “aviamento” (or, buying merchandise on credit).

The gathering of açaí is a male activity and demands a certain skill in the use of the “peconha”, a ring made of vines that is hooked onto the feet of the man and that helps him climb up the açaí trunk. The fruits are gathered in great quantities and brought to the village in baskets known as “paneiros”. In the making of açaí wine (or juice), it is necessary to put the fruit to soak in lukewarm water. After that, the fruits are mashed in a pestle to release the pulp from the seed and, finally, the liquid is sifted and consumed preferibly mixed with manioc flour.

Another important product in the lives of the Jiahui is the babaçu, the fruits of which can be consumed naturally or in the form of flour or gum. Babaçu leaves can be used to cover the rooves of houses. The Jiahui also like the puremu, the caterpillar that breeds inside the babaçu nut, and which is consumed fried. The oil eliminated is used to pass on the hair. According to the Jiahui this product is very effective in avoiding white hair.

The gardens are found in the proximities of the village. In general, the garden is cleared by the men in the dry season (between July and August) so that it can be burnt and planted at the beginning of the period which precedes the first rains. The cutting of the forest and burning are exclusively male activities, while the planting, weeding, and gathering involve the participation of the men, women, and children.

The principal product cultivated by the Jiahui is manioc, utilized in the production of manioc flour. Manioc flour has a central place in the food diet, being consumed throughout the year. They also plant banana, yams, watermelons, soft corn, beans and pumpkin. In exceptional cases, the Jiahui commercialize their agricultural surplus, but in general, production is consumed within the community or traded with neighboring kin (Parintintin and Tenharim).

Commerce is done with the gathered products, principally cashews and açaí, which are taken to the municipality of Humaitá. There is also production of artwork, done mainly by the women. Many collars, rings, bracelets and feather crowns are commercialized in Humaitá and Porto Velho. Artwork also has a strong element of identity, in the sense that the feather crowns are widely used by the men in political situations as a way of displaying the force of indigenous culture.

The Mboatava fest

The coming together of all Jiahui economic activities, as well as of the Kagwahiva in general, takes place through a festival, which is central to native culture. Every year, at the beginning of the planting season, the Kagwahiva prepare a great festival called Mboatava, a name deriving from the word for cashew. The main dish served in the ritual is tapir or taiaho (wild pig) meat cooked in cashew milk.

More and more, this festival has become the catalyzing pole for groups speaking the same language, constituting a political and identity reference-point for the Kagwahiva in general. In the last few years, the ritual has been held in the Tenharim villages and, besides uniting all the Kagwahiva, it has attracted the regional administrators of the Funai, missionaries, representatives of local government and NGOs. With the constitution of the Ju’i village and with the definition of their territorial limits, the Jiahui are strongly in favor of holding their own Mboatava festival. According to the jiahui Irá and Ñagwea’i, the festival held by the Jiahui was similar to that held by the Tenharim, but it had some of its own pecularities.

Sources of information

- ALMEIDA, Rita Heloísa de. O diretório dos índios : um projeto de “civilização” no Brasil do século XVIII. Brasília: Editora da UNB, 1997.

- BANDEIRA, Alípio. A cruz indígena. Porto Alegre : Livraria Globo, 1926.

- BETTS, La Vera. Dicionário Parintintin-Português Português-Parintintin. Brasília : SIL, 1981.

- CAVALVANTE, Idelfonso. Diário da Terra Indígena Rio Branco (Jiahui) do Amazonas. Manaus : s.ed., 1999.

- FERREYRA, Manoel. Breve notícia do rio Tapajós cujas cabeceyras últimas se descobrirão no anno de 1742. Évora : Bibliotéca Pública de Évora, 1752. (manuscrito não publicado)

- FREITAS, José Garcia de. Os Índios Parintintin. Journal de la Societé des Américanistes, Paris : Societé des Américanistes, n.18, n.s., p. 67-73, 1926.

. Relatório encaminhado ao Diretor do SPI Sr. Dr. José Bezerra Cavalcanti, pelo inspetor Bento Pereira de Lemos referente às atividades da IR 1 no exercício de 1930. Rio de Janeiro : Museu do Índio, 1930. (filme 33, planilha 396, p. 02-12)

- GONDIM, Joaquim. Etnografia Indígena : Estudos realizados em várias regiões do Amazonas, no período de 1921 a 1926. Fortaleza-CE : Editora Fortaleza, 1938.

- HUGO, Vítor. Desbravadores. 2 v. Humaitá : Missão Salesiana, 1959.

- KRACKE, Waud H. Force and persuasion : leadership in na Amazonian society. Chicago ; Univers. of Chicago Press, 1978. 340 p.

. A presença do sonho no xamanismo Tupi (Parintintin). Brasília : UnB, s.d.

- LEMOS, Bento Pereira. Relatório encaminhado ao Diretor do SPI Sr. Dr. José Bezerra Cavalcanti, pelo inspetor Bento Pereira de Lemos referente às atividades da IR 1 nos exercícios de 1925 (filme 33, planilha 396, p. 2-3; 33-44); 1928 (filme 33, planilha 396, p. 4-24); 1930 (filme 33, planilha 396, p. 02-12). Rio de Janeiro : Museu do Índio, 1925/1928/1930.

. Relatório encaminhado pelo inspetor Bento Pereira de Lemos referente às atividades da IR 1 nos exercícios de 1930 e 1931 (12/04/1932) : Índios Mura, Mundurucu e Parintintin. Filme 379, fotogramas 106-112. Rio de Janeiro : Museu do Índio, 1931.

- MACHADO, Luciana. Relatório ambiental da Terra Indígena Jiahui. Brasília : Funai, 2000.

- MENÉNDEZ, Miguel Angel. Uma contribuição para a etno-história da área Tapajós-Madeira. Rev. do Museu Paulista, São Paulo : USP, v. 28, p. 289-388, 1981/1982.

.Contribuição ao estudo das relações tribais na área Tapajós-Madeira. Rev. de Antropologia, São Paulo : USP, v.17/18, p.271-86, 1984/1985.

. Os Kawahiva : uma contribuição ao estudo dos Tupi Centrais. São Paulo : USP, 1989. (Tese de Doutorado).

. A presença do branco na mitologia Kawahiwa : História e identidade de um povo Tupi. Studi e Materiali di Storia delle Religioni, Roma : Japadre Ed., v.53, n.1, p.75-97, 1987.

- NIMUENDAJÚ, Curt. Os índios Parintintin do rio Madeira. Journal de la Socièté des Américanistes, Paris : Socièté des Américanistes, n.16, n.s., p. 201-78, 1924.

- PEGGION, Edmundo Antônio. Forma e função : uma etnografia do sistema de parentesco Tenharim (Kagwahív-AM). Campinas : Unicamp. 1996. (Dissertação de Mestrado)

. Os procedimentos na identificação de terras indígenas : relato de uma experiência. Boletim da ABA, Campinas : ABA, n. 29, p.12-4, 1998.

. Relatório de identificação e delimitação Terra Indígena Jiahui, município de Humaitá-AM. Cuiabá : Funai, 2000. 138 p.

- PEREIRA, Ednelson. Kagwahiva Jahoi : localização histórica e atual. Humaitá : Projeto Humaitá/Opan, 1998.

- TOCANTINS, Antônio M.G. Estudos sobre a tribu Mundurucu. Rev. Trimensal do Instituto Histórico Geográphico e Ethnográphico do Brasil, Rio de Janeiro : Garnier Livreiro e Editor, s.n., p. 73-161, 1877.