Rio Negro Ethnic Groups

- Self-denomination

- Where they are How many

- Linguistic family

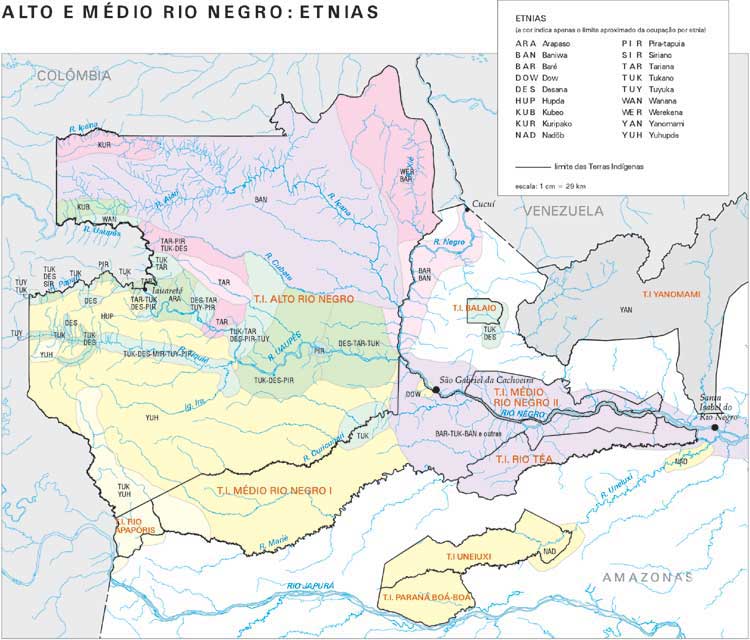

The region of the Northwest Amazon, which covers the basin of the Upper Rio Negro, where the border line between Brazil and Colombia traces a shape that looks like a dog’s head, has been traditionally inhabited for at least two thousand years by ethnic groups who speak languages belonging to three language families: Arawak, Maku and Tukano.

Direct contact

Despite the multilingualism and cultural differences, the 27 ethnic groups who inhabit the region – 22 of them being in Brazil – are part of a single culture area, and are in large part articulated by a network of trade, and identical in terms of their material culture, social organization, and worldview. This cultural area can be further subdivided in:

Ethnic groups of the Uaupés RiverArapaso, Bará, Barasana, Desana, Karapanã, Kubeo, Makuna, Mirity-tapuya, Pira-tapuya, Siriano, Tariana, Tukano, Tuyuca, Kotiria, Tatuyo, Taiwano, Yuruti (the latter three inhabit in Colômbia only) |

Ethnic groups of the Içana River |

The Maku ethnic groupsHupda, Yuhupde, Dow, Nadöb, Kakwa, Nukak (the latter two inhabit in Colômbia only) |

Ethnic groups of the Xié River |

Sociodiversity

With regard to factors such as geographical distribution, languages spoken and social organization, the 22 ethnic groups of the region of the Northwest Amazon can be divided into four groups, which are dealt with in different sections of the encyclopedia:

1) Ethnic groups of the Uaupés River: are distributed throughout this river basin and other basins to the south. Most speak languages of the Eastern Tukanoan family. They are organized into patrilineal, exogamic phratries and sibs (groups of desendants of a common ancestor who do not intermarry): Arapaso, Bará, Barasana, Desana, Karapanã, Kubeo, Makuna, Miriti-tapuya, Pirá-tapuya, Siriano, Tariana, Tukano, Tuyuka, Kotiria, Taiwano, Tatuyo, Yuruti (the last three listed are only found in Colombia).

2) Maku ethnic groups: These are located predominantly in the interfluvial regions along a line that runs in a general northwest-southeast direction, from the Guaviare River, in Colombia, to the Japurá, in Brazil, cutting through the Uaupés basin. They are organized in domestic groups (close kin of the husband and/or wife) and regional groups (agglomeration of neighboring villages), which speak dialects of the Maku language family: Dow, Hupda, Nadöb, Yuhupde, Kakwa, Nukak (the last two mentioned only live in Colombia).

3) Ethnic groups of the Içana and its tributaries the Cuiari, Aiari and Cubate. Speakers of Northern Arawakan languages: Baniwa and Kuripako.. They are organized into patrilineal, exogamic sibs and phratries.

'4) 'Ethnic groups of the Xié River and Upper Rio Negro: They inhabit the borderland region between Brazil, Venezuela and Colômbia. The majority speak Língua Geral, or nheengatu, introduced by the first missionaries, in the XVIIIth Century: Baré and Warekena [or Werekena].

Location and population

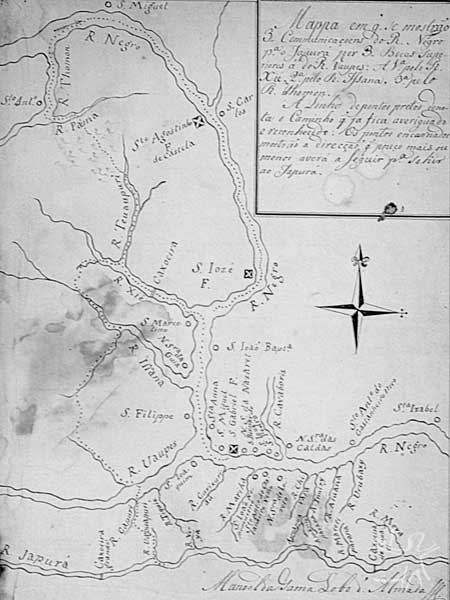

The principal river which cuts through this region is the Negro, tributary of the Amazon which, before it enters Brazil, is called the Guainía and separates Colombia from Venezuela. In its upper course, it receives the waters of the Içana and Uaupés (called the Vaupés in Colombia) on the right bank. The Rio Negro basin also includes the Apapóris River and its tributaries, an almost entirely Colombian tributary of the Caquetá, since it flows into the latter after passing along a small portion of the border with Brazil. From then on down, the Caquetá is known as the Japurá.

The headwaters of the hydrographic basin of the Içana River are in Colombia, but shortly after it delimits the border with Brazil, running through Brazilian territory in a southwesterly direction after a short stretch. The length of the Içana River is about 696 kilometers. The Uaupés River by contrast is about 1,375 kilometers in length. After the Rio Branco, the Uaupés is the largest tributary of the Rio Negro and, along its course, it also receives the waters of other large rivers, such as the Tiquié, the Papuri, the Querari and the Cuduiari. Above the mouth of the Uaupés is an area formed by the Xié River and the upper course of the Rio Negro.

The greater part of the region consists of Union lands (Indigenous Lands and a National Park). The present indigenous population makes up at least 90% of the total, although more than two centuries of contact and commerce between the native peoples and the “whites” has forced many Indians to migrate to the Lower Rio Negro or to the cities of Manaus and Belém, as well as having led people from other origins to establish themselves there. The presence of northeasterners, people from Pará, and people from other parts of Brazil and the Amazon is concentrated in the few regional urban centers.

In Brazil, the ethnic groups of the upper Rio Negro are located on eight Indigenous Lands – five of which have been ratified and are contiguous, two yet to be identified and one in the process of identification – located in the Amazonian municipalities of São Gabriel da Cachoeira, Japurá and Santa Isabel.

| Ratified Indigenous Lands | Total Area (Km²) |

| Upper Rio Negro | 79.993 |

| Middle Rio Negro I | 17.761 |

| Middle Rio Negro II | 3.162 |

| Apapóris river | 1.069 |

| Téa river | 4.118 |

| TOTAL | 106.103 |

It is possible to state that on the Upper and Middle Rio Negro there are presently 732 villages, varying in size from small settlements inhabited by only one couple to large villages and settlements scattered along the rivers of the region. The census of the indigenous population of the region has recorded a total of approximately 31 thousand Indians, a number which includes those who live in the city of São Gabriel da Cachoeira (around eight thousand in 1996) and Santa Isabel (around three thousand in 1996). The following table shows how the population of the various ethnic groups is distributed:

| Sub-regions(*) | Population (*) |

| Uaupés (including Traíra) | 9.290 |

| Içana | 5.141 |

| Rio Negro (Upper) e Xié | 3.276 |

| Rio Negro (Middle) | 14.839 |

| TOTAL | 31.625 |

*Data from 2000, including non-indigenous population of the cities.

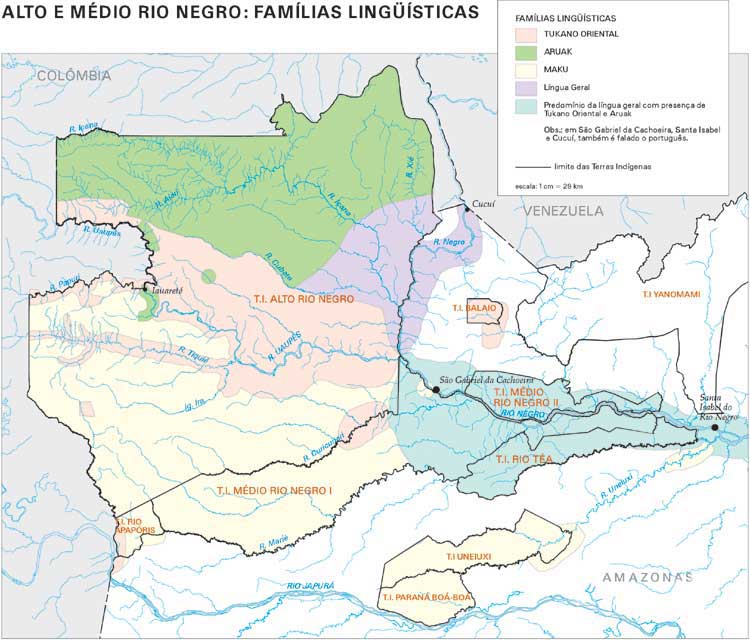

Languages

More than 20 languages are spoken in the Northwest Amazon, belonging to three major language families: Eastern Tukano, Arawak and Maku. The languages of the Eastern Tukano family. – so designated to differentiate them from the Western Tukanoans who inhabit the borderlands between Colombia, Ecuador and Peru –predominate on the Uaupés and Apapóris, while speakers of Arawak languages are more common on the Içana. Several languages, such as Tukano and Baniwa, are spoken by several thousands of people, and others, such as Dow, by only a few dozen.

There are at least 16 different languages classified as Eastern Tukano. In Brazil, speakers of Eastern Tukano inhabit the entire Uaupés River basin and, in a large part of these populations, there is a convergence between exogamic rules and linguistic groups, such that affinal groups (with whom one can marry) are speakers of other languages. This dynamic produces a multilingualism that is characteristic of the region, in which often in the same community more than one indigenous language is spoken, besides Portuguese and Spanish. Several ethnic groups, or parts of them, have ceased to speak their original languages, and have adopted other indigenous languages. This is the case of the Tariana of the Uaupés, who originally spoke an Arawak language, but who today speak Tukano; or the case of the Tukano who migrated to the Middle Rio Negro and adopted Nheengatu.

The principal language of the Eastern Tukano family is Tukano itself. It is spoken not only by the Tukano, but also by the other groups of the Brazilian Uaupés and its tributaries the Tiquié and Papuri. To the degree that there are various distinct languages, Tukano came to be used as a língua fanca [trade language], allowing communication among peoples whose paternal languages were quite different and which , in many cases, are mutually incomprehensible. In several contexts, Tukano has come to be spoken more than the local languages themselves.

The other languages of this family are spoken by smaller populations, predominating in more specific regions. This is the case of Kotiria and Kubeo on the upper Uaupés, above Iauareté; Pira-tapuya of the middle Papuri; Tuyuka and Bará of the upper Tiquié; and Desana from communities located on the Tiquié, Papuri and their tributaries.

The Arawakans are represented principally by the Baniwa, Kuripako, Baré, Warekena and Tariana. As mentioned, the Tariana speak principally Tukano, as a result of centuries of living together with the Tukano peoples of the middle Uaupés. The Baré also do not speak their original language any longer. As a result of contact with missionaries and colonizers, they have adopted the Língua Geral (or Nheengatu). Nheengatu is a simplified form of the ancient Tupi language, which was adapted and widely diffused by the first Jesuit missionaries. Currently, this language represents a mark of Baré cultural identity.

The designation Maku refers to six distinct languages of peoples who occupy the most extensive territory of the upper Rio Negro, four of which are located in Brazil. The Maku language family has no similarities whatsoever with the Tukano and Arawak language families, except for a few evidently borrowed elements. Practically all Maku speak their languages. Due to the nearness of the Tukano, the Maku of the Uaupés area also dominate Tukanoan languages, consistent with the multilingualism of the region.

Social organization

The social organization of the Northwest Amazon is different from most Amazon societies because of the existence of partilineal descent groups, which are named, exogamic, and ideally hierarchical. A complex social arrangement organizes these groups, in which the smallest unit is the sib, formed by the descendants of a unique ancestor and who consider themselves close kin.

Among the groups of the Eastern Tukano language family, the linguistic unit coincides with the agnatic kinship unit based on patrilineal descent, that also corresponds to the level of organization at which exogamy is most operational. For example, the Tuyuka linguistic group is formed by around fifteen sibs, among whom no marital exchanges occur. Thus, the Tuyuka establish their alliances with the Tukano, Bará and others.

In general, then, the exogamic descent group coincides with the linguistic group. The common notion of descent is revitalized in ritual proceedings. In indigenous terms, this unit is defined by a self-designation and a name by which they are recognized by others (Indians and Whites). The self-designation occurs in two spheres of social organization, the linguistic group (for example, Tukano, Desana, Kotiria, Tuyuka, and others) and the sib. The members of a sib ideally live together in the same local group. Still on the conceptual plane, each sib has a particular function, associated above all with ritual specializations. The anthropologist Christine Hugh-Jones, who studied among the Barasana, describes five ritual functions among the Barasana (chief, master of the cerimony, warrior, shaman and servant), related to the organization of labor, ritual performance and warfare. The localized sib has the maloca [longhouse] as its traditional dwelling place, which also bears important ritual and cosmological meanings.

In the case of the peoples of Arawak origin, such as the Baniwa, Kuripako, Werekena, Tariana and Baré, the correspondence between language, common descent and exogamy has not been observed by modern ethnography. The exogamic unit is the phratry: various sibs speaking the same language are grouped into phratries which, besides the rule of exogamy, maintain important alliances amongst themselves. In the case of the Tariana, who occupy the region of the middle Rio Uaupés (where the Eastern Tukano peoples predominate), one observes that they are integrated as one of the descent groups within the Uaupés social system. Although they have mostly adopted the Tukano language, they function as a linguistic group that exchanges women with their allies, especially the Tukano, Kotiria and Pira-tapuya. The Baré, for their part, inhabit the channel of the Rio Negro, in the vicinity of the city of São Gabriel da Cachoeira. The present-day social organization and forms of marriage among the Baré in Brazil have still not been described in the ethnological literature.

Among the Maku, the social organization of the linguistic groups can be characterized in terms of three levels: the domestic hearth groups, organized around a married couple; the local groups, clusters of domestic hearth groups, which have the eldest man of the groups as focal point; and the regional groups, organized territorially in relation to streams or small rivers. The regional groups are endogamous, with specific cultural traits and distinct dialects. Each linguistic group can include three or more regional groups.

In this context of cultural diversity, there are many common characteristics among the ethnic groups, principally with regard to the myths, subsistence activities, traditional architecture and material culture. Such common features are more evident among the Tukano, Baniwa, Tariana and Baré, on the one hand, and the Maku, on the other. For that reason, the first are sometimes identified as the “river Indians". By contrast, the Indians of the Maku linguistic family, who are distinguished by a number of socio-cultural peculiarities, can be called the “forest Indians". Living far from the banks of the navigable rivers, the Maku maintain relations with the river Indians, but not in the same way that they maintain relations amongst themselves. The Maku, outstanding hunters, in general provide meat to the Indians of the river and also provide them services in exchange for other foods, such as manioc and fish.

From the point of view of the river Indians, the Maku occupy a position of inferiority and are considered incestuous, for they marry people of the same descent group and do not follow the same residence patterns. However, from the Maku point of view, they are not servants or slaves of the river Indians, and can at will abandon the services they provide for the river Indians and slip back into the forest, which is populated by spirits that are unknown and feared by the river Indians.

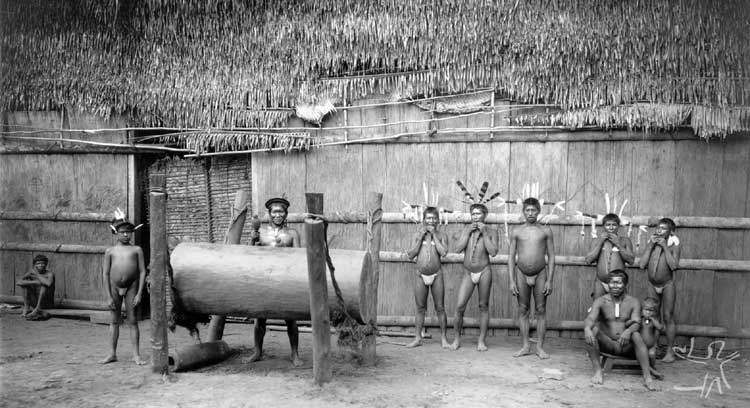

Malocas [Longhouses]

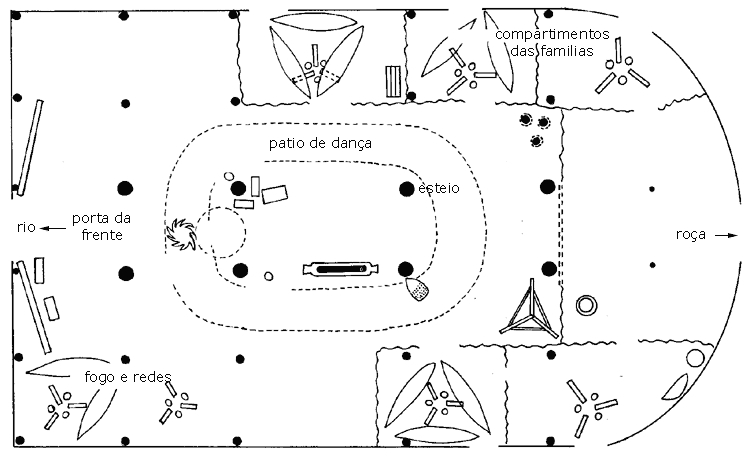

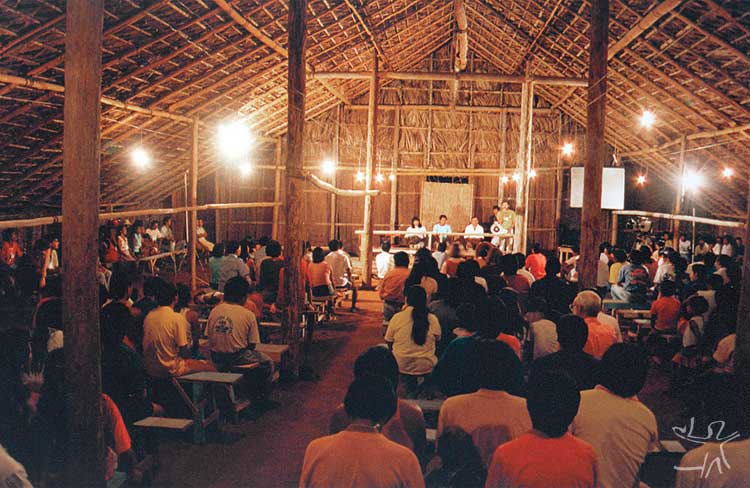

The building of longhouses is a custom shared among the different indigenous societies of the Upper and Middle Rio Negro. For many years these constructions were the object of attacks on the part of missionaries, which resulted in their abandonment by the majority of the communities located on the Brazilian side of the region. Actually they are being recovered in several places, such as on the upper Tiquié and the upper Uaupés, in the context of a process of recovery of traditions and as a badge of identity for the indigenous movement, as is the case of the longhouse at the headquarters of the Foirn (Federation of the Indigenous Organizations of the Rio Negro), in São Gabriel.

Traditionally, the longhouse was divided into various side compartments, each one occupied by a nuclear family. The general rule was that the chief of the local descent group lived in the compartment nearest the wall of the back of the house, to the left side of whoever entered the back door, and his younger brothers, as they married, occupied contiguous compartments, from the back to the front of the house. The unmarried men, already initiated, had to leave the compartment of their parents and hang their hammocks from the center beam in the middle of the house towards the front. Finally, the aggregated inhabitants who were living in the house provisionally or on an exceptional basis, and visitors, had to remain in the front part of the house.

During the festivals and above all in the more formal cerimonies, that involve dances of the adult men, the longhouse space is re-arranged, the center of the longhouse being the most important area, where the dance takes place.

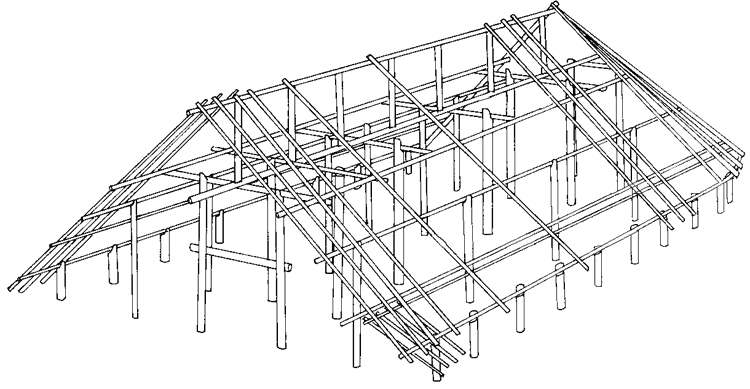

The Salesian missionary Alcionilio Brüzzi made a detailed description of the longhouse of São Pedro, on the Rio Tiquié, which he visited in 1947, but which can be generalized for the longhouses that used to exist in great number throughout the region:

"It was built according to the old ways. It was rectangular, measuring 27.60 metres in length and 18 in width. The roof was sloping on two sides, with a marked decline, to facilitate the quick flow of rainwater. Inside it measured 7.30 metres in height at the center beam, but sloping down to 90 cm from the ground, such that the side walls measured only 1. 52 meters in height. The thatched roofing extended out a bit more on the part corresponding to the doors, for protection from the rains. The main walls were made in the classic style, that is, out of treebark up to 2.5 meters in height, and tied together with açaí. The side walls were made of pehé.

It was solidly built on five pairs of poles [the three center poles and the other two which held up the front and back walls of the longhouse], which marked the central nave. They were rounded poles, rectilinear, rustic (without removing the bark), although quite regular and proportional, as also were the beams and rafters.

The whole wooden frame was solidly tied with vines. Inside, the supports, all well aligned, divided the space into five naves [from one side to the other]. The three center naves are for common use: transit, meetings, dances, visits and work. There, more to the back, the utensils of common use were kept, such as the large vessels of fired clay and the wooden troughs for the fermentation of the caxiri beverages, and the oven for the cooking of manioc flour. It was in this area that the dances were held on the occasion of the festivals. The two outside naves, which correspond to the lower part of the sloping roof, along the border, are set aside for family residences: each nave has four divisions.

In the residence of the chief, the separation is a bit more pronounced, but not enough, however, to hinder a view of inside the longhouse. In several longhouses, absolutely no separation exists. One can thus say that they are imaginary divisions, corresponding to the wooden beams and poles of the longhouse" (1962:175-7).

Today, most of the Indians who live along the banks of the main rivers are organized into “communities”, a name that has been used for decades by the Catholic missionaries – and also used by the Protestants - to refer to the villages which came to substitute the communal longhouses. The community is generally comprised of a set of houses built on a wide open plaza, with walls of treebark, mud walls, or boards and rooves of thatch or sheets of zinc, A community also has a chapel (Catholic or Protestant), a small school, and, in some communities, a health post. Each community has a captain [ capitão], always a man, whose role is to bring the group together, “animating it" to perform community tasks and also answering to the general demands linked with such tasks. One is not dealing, however, with an all-powerful chief or commander who gives orders and can punish. In most cases, he only guides, without imposing his point of view. He is also the preferred interlocutor with the whites.

Religious life and ritual

An important characteristic of the cultures of the region is a ritual complex involving the use of sacred flutes and trumpets, associated with a mythology the central themes of which include initiation, the ancestors, warfare and the seasonal cycles. By means of the powers of the shamans, hallucinogenic substances and contact with the musical instruments, the participants in these cerimonies reunite with the mythical past and social structure gains greater visibility.

Thus, despite the many local variations, there are several ritual structures that are shared by the Tukano, Arawak, and Maku peoples which integrate the culture area of the Northwest Amazon.

History of contact: XVIIth and XVIIIth centuries

Since the mid 17th Century, with the drastic decrease in the indigenous population of the Lower Amazon, as a result of slavery and epidemics of yellow fever, there was an enormous need for manual labor for work on the ranches and in the harvesting of “backland drugs” [i.e., spices, etc.]. The colonists and missionaries of São Luís and Belém thus were led to make incursions into the backlands of the Rio Negro and Amazon, capturing Indian slaves and massacring those who resisted: these were the “ransom troops” and the “just wars". The Fort of Barra de São José do Rio Negro (where today the city of Manaus is located), built in 1669, served as a base for future expeditions in search of slaves.

In the first half of the XVIIIth Century, after the defeat of the Manao and Mayapena, who dominated the Lower and Middle Rio Negro and who had previously collaborated with the Portuguese in obtaining slaves, the Portuguese reached the region of the Upper Rio Negro and its principal tributaries, the Uaupés, Içana andXié, which were still densely populated and practically not affected by the Whites. In this period, the Carmelites established settlements up to the Upper Rio Negro, in the vicinity of the present-day city of São Gabriel da Cachoeira. The commerce in slaves became so intense in the 1740s that it was estimated that by the mid-XVIIIth Century, around 20 thousand Indians had been taken prisoner and made to descend the Upper Rio Negro. Unknown numbers of slaves were also taken by private slavers who worked independently of the official slave trade. In the official lists of slaves removed from the region, are included a large number of Tukano, Baniwa, Baré, Maku, Werekena and others who today live in this same area, brought to work in Belém and São Luís.

As a result of the contact with the Portuguese, a smallpox epidemic devastated the Upper Rio Negro in 1740, killing a large number of Indians, for it is quite probable that it may have spread through parts of the region where no direct contact had been made with the “whites”, by means of cotton cloth and clothes. Between 1749 and 1763, recurrent epidemics of smallpox and measles repeatedly swept the region, the measles epidemic of 1749 being so terrible that it came to be called “big measles".

The most famous indigenous revolt of this period was that of 1757, led by the chiefs of the town of Lamalonga on the Middle Rio Negro. This rebellion marks the revolt of the Indians against the missionaries, which is attested by the destruction of the chaples and religious paraphernalia and the killing of a Carmelite priest.

In the second half of the XVIIIth Century, the Portuguese government under the direction of the Marquês de Pombal removed the “temporal power” of the missionaries. They lost control over the administration of the villages, which were then put under the administration of the colonists, civilians or military, who also were given the title of “Directors of the Indians". The missionaries were, nevertheless, authorized to stay in the villages to go on with the work of catechization and persuasion of the Indians at the headwaters of the rivers and streams to come downriver and settle in the villages of the middle and lower Rio Negro. Even so, there was a notable decline in the missionary work. The most prosperous villages were promoted to the category of towns, and were given Portuguese names, which were often saint names. The decrees of the Marquês de Pombal sought to put an end to slavery and promote the assimilation of the Indians into colonial society.

The Marquês de Pombal wished to grant to the Indians the same rights as the Europeans, but he soon understood that the colonists depended for their survival on indigenous labor, both in agriculture and in the extraction of forest products. He established a system of labor in which part of the men in good health would work for several months a year on the building of houses in the colonial towns, while others would take care of the plantations. But this system of labor organization was not respected and the Indians continued to be exploited by the colonists. Hundreds of them were taken to the colonial towns during this period.

With a base in the forts built in 1763 (São Gabriel and São José de Marabitanas), Portuguese military explorers made exhaustive journeys over the upper tributaries of the Negro, a strategic region due to its location on the borderlands between the Portuguese and Spanish colonial empires, especially after the signing of the Treaty of Madrid in 1750.

For the indigenous peoples, this period meant the near complete opening of their territory by the Portuguese military, and also the increase in depopulation of the villages as a result of the “descents”, a veiled form of slavery which put the Indians to work on the boats and on agriculture. The costs of this policy for the Portuguese were high, for it provoked numerous revolts and desertions of the settled Indians, and the constant necessity of replenishing the labor force necessary for the production of indigo and manioc and the gathering of cacao.

History of contact: XIXth Century

From the beginning of the XIXth Century, the region of the Rio Negro was missionized by the Carmelite friar José dos Santos Inocente (1832/52), the Capuchin friar Gregório José Maria de Bene (1852/54) and by Franciscans (1880/83), who, together with the military, had a strong participation in the repression of the Indians and the exploitation of their labor, principally in extractivism. At the same time, merchants, called regatões, began to penetrate on the Rio Negro, which was often marked by violence, for example when they took even Indian children captive to sell them to businessmen in Manaus and Belém, as the naturalist Alfred Russel Wallace pointed out in 1853.

From 1835 to 1840, the great popular rebellion of Brazil, called the Cabanagem, which began with the taking of the city of Belém, reached the Rio Negro. This led to a process of repression of the rebels which was concluded around 1840. After this period, the Military Command located in Belém sent a troop to the Upper Rio Negro, for the purpose of rebuilding the forts of São Gabriel and Marabitanas, then in ruins, for which the work was entirely done by the Indians. The Military Command also created the “Company of Laborers” in the region, to which the “domesticated Indians”, that is, those who knew how to speak Portuguese, were summoned to participate. This return of the military caused a setback in the relations between Whites and Indians in the region, from around 1840-42.

Several smallpox and measles epidemics devastated extensive parts of the Rio Negro during this century, which caused the flight en masse of the Indians from the villages and the colonial towns. In these periods of repeated epidemics, intermittent fevers [malaria], at times characterized as “malign” or “pernicious”, greatly contributed to the high mortality in the region.

In the mid-XIXth Century, the government of the recently-created Province of Amazonas attempted to convince the Indians to abandon their dwellings in withdrawn regions, difficult of access, and to live in the settlements and towns on the banks of the main rivers. The government also sought to keep a certain number of Indians in Manaus for construction work, which led to a depletion of the population in many indigenous communities of the Uaupés, Içana and Xié rivers, the families of which were taken by force to the Lower and Middle Rio Negro. Many Indians were involved in the extraction of sarsaparilla and rubber, which was just beginning at that time, and submitted to forced migration, being transported by the merchants from the Upper Uaupés, to work. This is the main reason for the actual presence of a significant population of their descendants on the Middle and Lower Rio Negro.

On various occasions, the Indians rebelled against this type of treatment and conducted expeditions in vengeance against the whites, who did not hesitate to use soldiers or even Indians of other ethnic groups of the region to repress the rebellions.

These rebellions were also expressed through religious movements. Indeed, there is an important tradition of religious movements in this region beginning in the middle of the XIXth Century. The leaders of these movements elaborated a variety of messianic messages and ideologies, and organized rituals and cerimonies expressing the millenial hopes of the peoples. Several of the leaders of the mid-XIXth Century, such as the Baniwa prophet Venâncio Kamiko, or Venâncio "Christ", as he came to be known, a very powerful Baniwa shaman who settled on the Rio Içana, preached freedom from the political and economic oppression of the Whites.

The movements spread throughout the entire region and threatened to expel the Whites. The local and provincial military reacted to these movements most of the time with violent repression, although the provincial government in 1858 sent an official commission to ‘tranquilize’ the situation. Around 1880, an Arapaço shaman of the lower Uaupés, who was called Vicente Christu, began to preach that he communicated with "Tupã" (Spirit of Thunder, who is part of the Tupian pantheon, but who was introduced by the missionaries along with the língua geral among the Indians of the Upper Rio Negro) and with the dead. He preached the end of the exploitation by the rubber bosses and their expulsion from the region. He foresaw the arrival of missionaries who would protect them from the bosses, the military and the merchants. He even proclaimed – as had Alexandre Christu in the mid-XIXth Century movements – a new social order, in which the Indians would be the bosses and the whites their slaves. There were several other movements of this type in the region in the first half of the XXth Century, several of which were violently repressed by the military.

History of contact: XXth Century

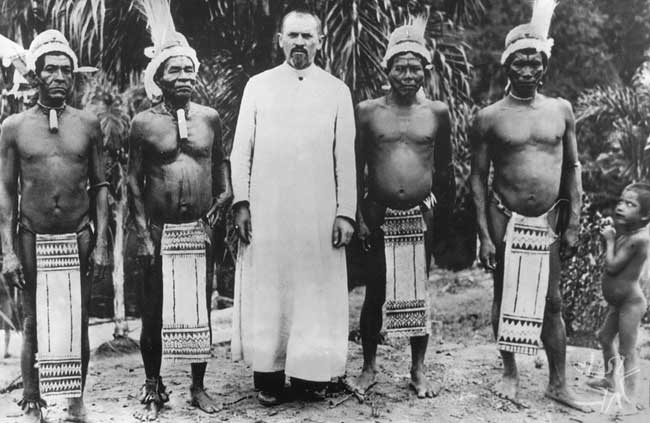

The activities of the missionaries resumed in 1883 with the arrival of Franciscans on the Uaupés. The Indians were obliged to set aside one day a week for building the houses of the religious and military authorities, the church and the prison. The Franciscans attempted to eradicate the activities of the local shamans and exercise control over the river merchants, who could only conduct commerce with the Indians with their authorization.

One of these Franciscans, Friar Illuminato Coppi, is described in the historical sources as a violent man, intolerant, who didn’t hesitate to ridicule the indigenous customs and beliefs. On several occasions, he exposed the sacred masks and musical instruments to the women and children – who are prohibited, on pain of death, from seeing them. His last provocation, which took place on October 28th, 1883 in Ipanoré, led to the revolt of the Indians of the village and the expulsion of the Franciscan missionaries.

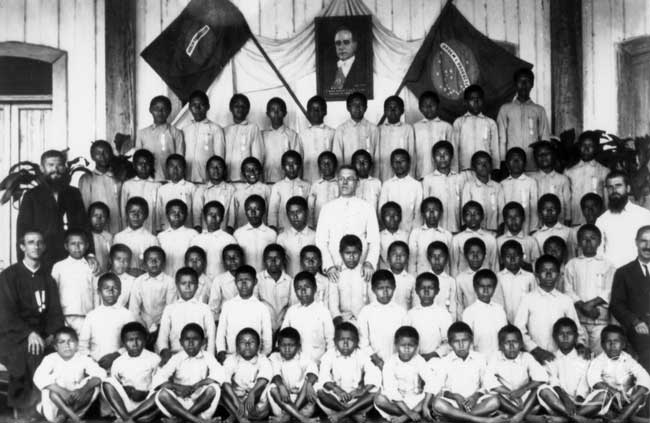

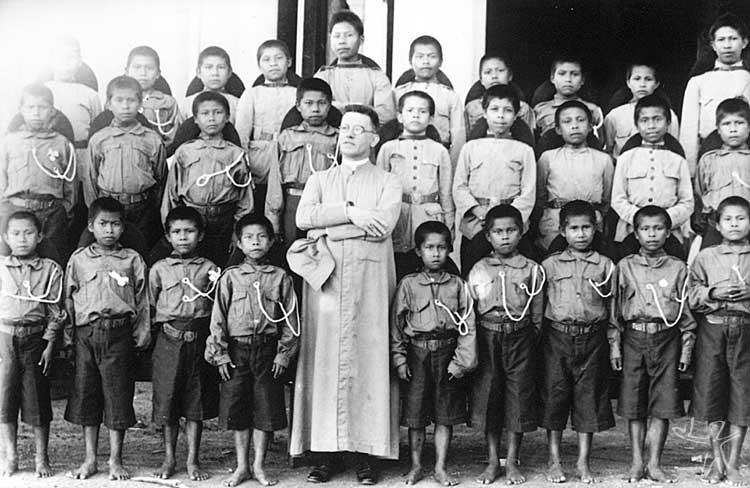

After the missionaries had left, the Indians went back to their longhouses. Missionary activities in the region only started up again in 1914, with the creation of the Apostolic Prefecture of the Rio Negro in São Gabriel da Cachoeira and the arrival of the Salesians. The congregation of Dom Bosco demonstrated that it was very well organized, with clear objectives and strategies and personnel quite willing and prepared for the “difficulties of this apostolic mission".

The first decades of their presence in the region were marked by major upheaval. No doubt, it meant a reduction of the abuses by the rubber bosses who predominated until then. But, on the other hand, the Salesians also took advantage of the state of submission and fear in which they found these people to implement their supposedly “civilizing” project. Demonstrating a deep disdain for the forms of organization and thought of the Indians, they sought from the beginning to destroy the cultural manifestations of these peoples. This attitude in relation to indigenous culture is easily observable in the various publications of the Salesians.

The Salesians considered that they would only succeed in penetrating the consciousness of the adults and elders by way of the children, after these had been trained through a severe, Christian education. In this way, the life of the children at the Mission was marked by extreme rigour and discipline: the times for all daily activities were rigidly set and had to be obeyed, the separation of the sexes was absolute, the use of indigenous languages was expressly prohibited, even for the newcomers who didn’t speak a word of Portuguese. The Salesians also greatly insisted, and ended up succeeding, in convincing the Indians to abandon their longhouses and to settle in villages comprised of separate houses for each family, under the pretexts that the longhouses were not healthy places and encouraged sexual promiscuity. They also discouraged the Indians from practicing the male initiation rituals (rituals of “Jurupary”). They waged defamatory campaigns ridiculing the activities of the local shamans, they prohibited the consumption of hallucinogenics, they removed cerimonial adornments and musical instruments from the indigenous longhouses.

Yet, with their permanent installation on the upper Rio Negro, and due to the fact that they created, at that time, the only infra-structure of assistance to the Indians, the Salesian missions little by little increased their activities, coming to assume, for awhile, control over health, education, and commerce in the region. They helped to control the situation of exploitation of the Indians, although they had minimal effects on the Içana, where they only established a mission in the 1950s.

The year 1970 was an important mark in the recent history of the Brazilian Amazon. The federal government, then controlled by the military, publicly announced the National Integration Plan (PIN), a program to develop the infra-structure for the purpose of geopolitically integrating the region with the rest of the country, which also had effects in the region of the Upper Rio Negro.

Between 1972 and 1975 the first effects of the Program appeared, with the installation of FUNAI posts and the arrival of military personnel from the Engineering and Construction Battalion and workers from companies contracted for the construction of highway BR-307 (connection between São Gabriel and Cucuí) and of a stretch of the Northern Perimeter Highway (BR-210), today abandoned. In 1979, with the cutback in federal funds, the Salesians decided to close the boarding-school system. The first school to be closed was the male boarding-school at the mission headquarters in São Gabriel da Cachoeira. In 1984, a report of the Salesian mission registered 501 students still in the school. Between 1985 and 1987 the boarding schools of Iauareté, Taracuá, Pari-Cachoeira and Assunção of the Içana were closed, as was the female boarding-school in São Gabriel.

In 1983, gold was discovered in the Traíra mountains by Tukano Indians of the Tiquié, which triggered a “gold fever” that spread to several points in the region for more than a decade, attracting Indians and initially gold-panners from other parts of the country and inhabitants of São Gabriel and, later, mining companies, who invaded the Traíra mountains and the region of the upper Içana.

The impacts of these changes were seen in the rapid growth of the population of the city of São Gabriel da Cachoeira which doubled in size, totalling some 4,500 inhabitants, according to estimates made in August, 1985. The "swelling" of São Gabriel was due, in part, to the collateral effects of the gold “fever”, but also to the fact that, without the boarding-schools, many families had to “open” houses in the city for their children to live during the school year.

Evangelicalism on the Içana

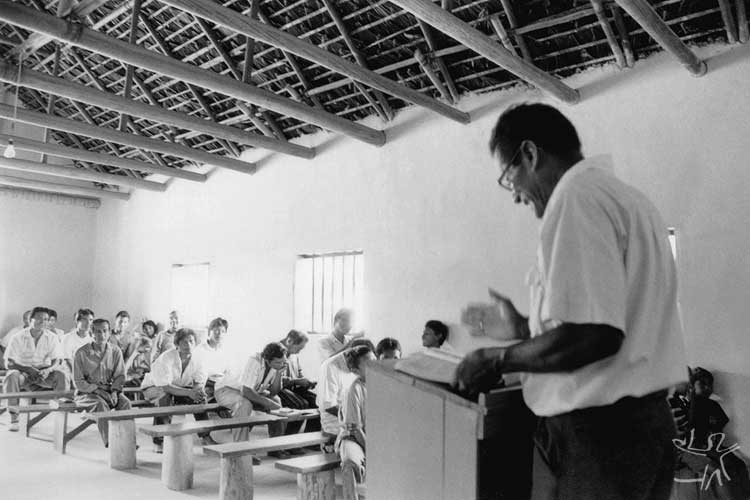

At the end of the 1940s, Sophia Müller, a North American evangelical issionary of the New Tribes Mission (NTM), began to evangelize among the Kuripako in Colombia, extending this work to the Baniwa of the Içana in 1949 and 1950. At least in the beginning, the conversion of the Baniwa bore all the signs of a millenarian movement, consistent with the prophetic traditions of these Indians beginning in the XIXth Century and continuing up to and concomitant with her introduction of fundamentalist evangelicalism. With her anti-Catholic propaganda, and her messages which preached redemption and the end of suffering, the missionary sparked a movement which led to the conversion of the majority of the Indians of the Içana. Many Baniwa considered Muller a prophet, and came from all over the region to hear her preaching and convert to the new faith. Greatly exploited by the rubber bosses and river merchants, while they sought to keep their distance from the whites, the Baniwa accepted evangelicalism as a form of resistance to white domination

In this period, the Salesian Mission of Assunção was built on the lower Içana, in an effort to contain the advances of evangelicalism. It had no influence, however, over the evangelical communities upriver. Thus was produced a division between ‘crentes’ [believers] and Catholics which has lasted until today.

The indigenous evangelical communities of the Içana integrate a system called United Biblical Churches, administered by locally selected indigenous elders and deacons. Along each stretch of the river, a group of communities participates, on a rotating basis, in a system of monthly Santa Ceias [Holy Suppers, comemorating the Last Supper]. Every three or four months, there are “Conferences”, events promoted by the communities of two contiguous stretches of Santa Ceia communities and open to invited guests.

Indigenous lands and organizations

The following is a summary, in the form of a chronology, of the most significant events in the history of the struggle for the demarcation of the Indigenous Lands of the Upper Rio Negro:

•1971: Indigenous leaders of the upper Tiquié and Uaupés, encouraged by the Catholic missionaries, began to demand the demarcation of their lands. FUNAI’s response is slow;

•1979: The Funai declares to be of “indigenous occupation” three contiguous areas: Pari-Cachoeira, Iauareté, Içana-Aiari. Leaders from the Tiquié send a proposal for the delimitation of the Upper Rio Negro as a continuous area (a proposal which was made again in 1981);

•1984-85: The Funai makes a proposal for delimitation of three more areas: Taraquá, Cubate, Içana-Xié, and proposes the inclusion of the region of the Traíra mountain, recognized as being of permanent possession of the Maku, within the Pari-Cachoeira Indigenous Area. In January, 1985, leaders assembled in Taraquá send a new proposal for delimitation of the region of the Upper Rio Negro as a continuous area. A Work Group from the Funai prepares a proposal to delimit the region of the Upper Rio Negro as a continuous indigenous reserve with identical surface area;

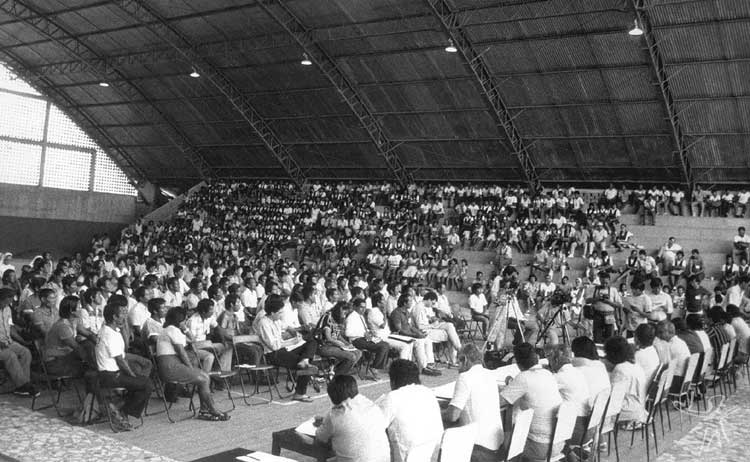

•1986-87: Growing resistance from the military sectors, especially the National Security Council against the demarcation of extense and continuous indigenous lands located on the borderlands. The Security Council essentially superceded the administrative power of the Funai. The Upper Rio Negro became the principal laboratory of the military for implementing the strategy of demarcating, reducing and fragmenting the Indigenous Lands located on the borders. The National Security Council negotiated with the Tukano of the Tiquié, a process which culminated in the holding of a large assembly of leaders in April, 1987.

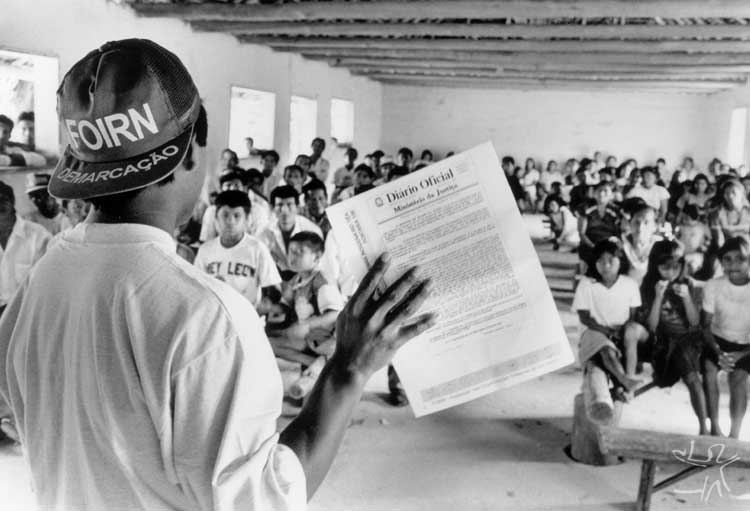

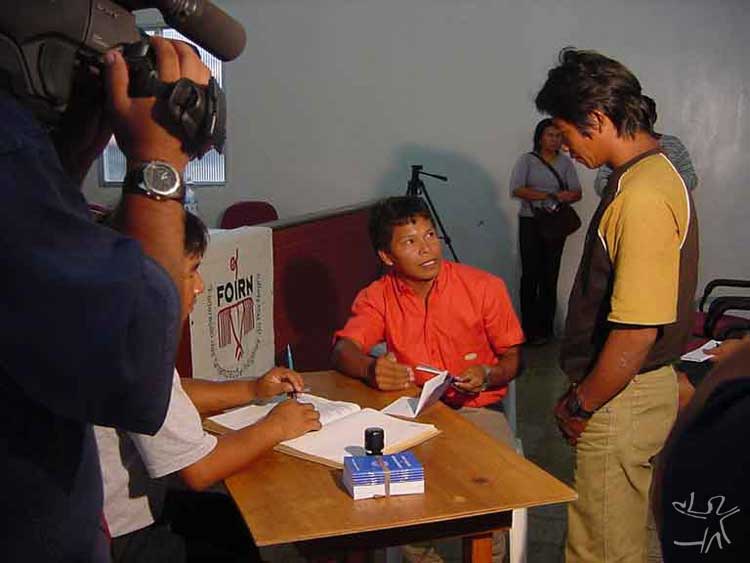

More than 300 indigenous leaders from various ethnic groups assembled in São Gabriel da Cachoeira for the 2nd Assembly of the Indigenous Peoples of the Upper Rio Negro at which representatives of the federal government, the state government, the church, mining companies and indigenist organizations were present to discuss the Northern Channel Project, mining company activities, and the regulating of Indigenous Lands. The assembly was unanimous in demanding the urgent demarcation of a continuous area, rejecting the proposal of the National Security Council. On that occasion, the Federation of Indigenous Organizations of the Rio Negro (Foirn) was founded, the principal mission of which was to struggle for the demarcation of a continuous area. In response, the National Security Council proposed an intermediate solution, consisting of a mosaic of Indigenous Colonies and National Forests (Flonas);

•1989-90: Presidential decrees ratify the administrative demarcation of three Indigenous Areas in Pari-Cachoeira; and create two Flonas in Pari-Cachoeira. Following this, other decrees ratify the administrative demarcation of indigenous areas in the old reserves of Iauareté, Taraquá, Içana-Xié, Içana-Aiari and Cubate; other decrees created nine more Flonas (National Forests) in the region. The indigenous areas, or “islands” were actually physically demarcated, however most of the concrete markers put in place by the Army were ripped out by the Indians and thrown into the river. The Indians filed a complaint in the Ministry of Justice, making use of instruments of the new Federal Constitution then in effect;

•1990-92: The Federal Public Ministry proposes a Declaratory Action before the Federal Justice against the Union, the Funai and Ibama, with the objective of recognizing the traditional occupation of the Indians of the upper Rio Negro to a continuous area, and the repeal of the decrees that created the 14 Indigenous Areas and the 11 Flonas. Two years later, an expert anthropological report was requested on the area. Also the definition of a new technical system for the demarcation of Indigenous Lands made it possible for a new technical opinion to be approved which joined the discontinuous Indigenous Areas together as well as encompassing the areas of the Flonas, once again establishing the limits of the so-called Indigenous Area of the Upper Rio Negro according to the desire of the Indians. The Foirn repeated to the authorities their demand to demarcate the Upper Rio Negro as a continuous area;

•1993-95: The proposal for administrative review of the Indigenous Lands of the Upper Rio Negro continues on its way through the official channels of the Ministry of Justice, going through various negotiations with the military sectors until finally, between December, 1995, and May, 1996, the Minister declared the area to be one of permanent possession of the Indians and delegated to the Funai the administrative demarcation of five contiguous indigenous lands in the region of the upper and middle Rio Negro;

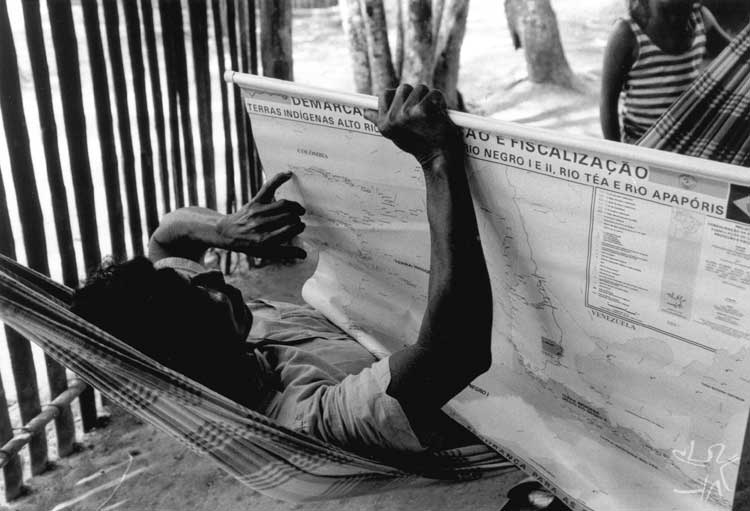

•1996-1998: The Funai relinquishes the task of the direct administration of demarcation and the Foirn officially indicates the Instituto Socioambiental (ISA) to take on the task. The ISA and the Foirn formulate a project for the consolidation of the demarcation and a plan for protection and fiscalization of the area. Demarcation is done between April, 1997, and April, 1998. Finally, on April 15, 1998, during the 6th General Assembly of the Foirn, the Minister of Justice delivers the ratification decrees for the five demarcated Indigenous Lands, which was commemorated by the leaders as an historic victory.

Having concluded the demarcation phase, the Foirn and affiliated associations, with the support of various partnerships, went on to concentrate its work on the great challenge of formulating a program of long-term ethnodevelopment for the region of the Upper and Middle Negro, including activities related to protection, fiscalization, technical training, cultural expression and sustainability of the indigenous communities (agroforestry management, pisciculture, comercialization of artwork and other products, implantation of indigenous schools, training of indigenous health agents, publication of works by indigenous authors and others).

Ecology and resource management

The Rio Negro is the largest blackwater river of the world. Specialists characterize these waters as being extremely acidic and poor in nutrients. The soils that they drain are usually greatly impoverished by leaching. This poverty in nutrients has an effect on the lives of the fish which, in order to sustain themselves, obtain a greater part of their food from organic matter found principally on the banks of the rivers(various types of insects, fruits, flowers, leaves and seeds). The opposite occurs on the whitewater rivers, which are rich in nutrients, as is the case of the Amazon and Solimões. These conditions of the riverine environment have also had an influence on the composition of the species of fish. Although there are several species of larger size, such as the pirarucu, the rivers of the Rio Negro basin are characterized by a large number of smaller species, each with a small number of representatives.

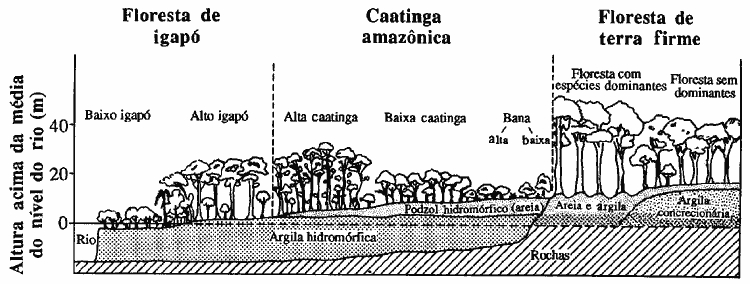

The Rio Negro basin presents a certain variety in vegetation types. The main ones are: terra firme forest, which occupies higher lands that escape flooding; open grasslands, grasslands with transition to forest or Amazonian stunted forest, a kind of low forest, bushy, varying between six and twenty meters, which grows on white sandy soils, flooded during the heavy rains, and which, in its poorest form, consists of very low and sparse bushes (three to six meters) , interspersed with creeping vegetation; floodland vegetation, which most of the time is underwater (for 7 to 10 months a year) which, while it has a smaller number of species in comparison with the terra firme forest, it is more diversified than the caatinga stunted forest; and heath, an area of localized vegetation on the banks of the rivers which remains flooded all of the time.

This diversity of natural landscapes of the Upper Rio Negro has a direct relation with the distribution and availability of natural resources important for the lives of the populations of the region (game, fish, fibres and thatch for constructions and utensils, fertile lands for agriculture and so on). The areas of Amazonian scrub forest, flooded lands, besides the heaths, are totally inadequate for agricultural activities. Thus, for example, bitter manioc (maniva), a plant which is perfectly well-adapted to the ecological characteristics and limitations of the region, cannot be cultivated on flooded lands. For that reason, the gardens are always cleared on terra firme.

The great variety of types of cultivation of manioc among these populations is particularly notable, making the region a pole of high agro-biodiversity. In the indigenous gardens of the upper Rio Negro, tons of leaves and debris and different stages of growth of the plants reveal a complex system, in which the central element of management is focused on the maintenance of diversity as a value in itself, since there is no direct relation between the use of a certain variety of manioc and a specific product (manioc flour, manioc bread, porridge, fermented manioc beverage, spices etc.), thus fitting into a logic which is the opposite of modern agriculture, which gives priority to homogeneity and productivity of the cultivation.

The conservation of such diversity is thought of as a collective good that is an integral part of a common cultural reference that is expressed, for example, through the myths of the origin of agriculture or cultivated plants. Moreover, it has patrimonial value and its circulation obeys collective rules.

The flooded lands, where the fish lay their eggs, are areas of recognized productivity in fishing, and are preserved for this purpose by the Indians. Areas of flooded lands are also rich in vines and rubber latex. The areas of scrub forest on the other hand are sources of straws, thatch, sororoca etc., raw materials for the covering of their houses. The brush – often areas of former gardens - are the preferred habitat of small animals which are highly prized by the Indians (cutias, acutivaras), and are also rich in medicinal plants. When the brush areas are left to fallow for twenty or thirty years, often, they are re-used by the Indians for new gardens. They demand less effort to be cut down and dry out after a few days of sun, which makes their burning quicker. The areas of brush are also valued because there are cultivated species which go on bearing fruit for many years, such as the peach-palm, buriti, caju, cucura and others.

The strategies employed by the indigenous populations, developed over centuries of occupation and experience in this region, have made it possible for them to deal with the general poverty of its ecossystem, without degrading it and impoverishing it, thus securing the ecological balance on the upper Rio Negro. Among these careful and rational management practices of the natural resources, several stand out:

- The economic exploitation of differentiated ecological zones gives rise to the relations of economic and ritual trade among the various indigenous populations;

- The emphasis on bitter manioc agriculture through the slash-and-burn system, which consists of cutting down an area of primary forest or high secondary forest, which is then left to dry out and is later burned. The gardens planted in these clearings, which remain productive for two to three years, are gradually abandoned, although they continue to be visited for gathering fruits with a longer maturation cycle. Each family has at least three gardens in different stages of development, besides continuing to exploit their old gardens no longer in use;

- In general the gardens are cleared in areas of terra firme, far from the riverbanks, in such a way as to preserve the principal sources of food derived from fishing activities;

- The high degree of specialization in fishing techniques (fixed traps called paris, matapis or cacuris) and the extensive knowledge of the seasons through an elaborate astronomical calendar allows them to accompany and take advantage of the cycles of high and low levels of the rivers and the migratory, reproductive, and feeding cycles of the fish;

- The mechanisms for circulation and redistribution of the natural resources among the phratries, through the system of matrimonial alliances based on linguistic exogamy (speakers of the same language must marry out of their linguistic group), as well as the formalized rituals of food exchange and the exchange of other goods( called dabucuris), which allow individuals to have access to natural resources that are not available in a given territory, promote rational economic exploitation on a regional level.

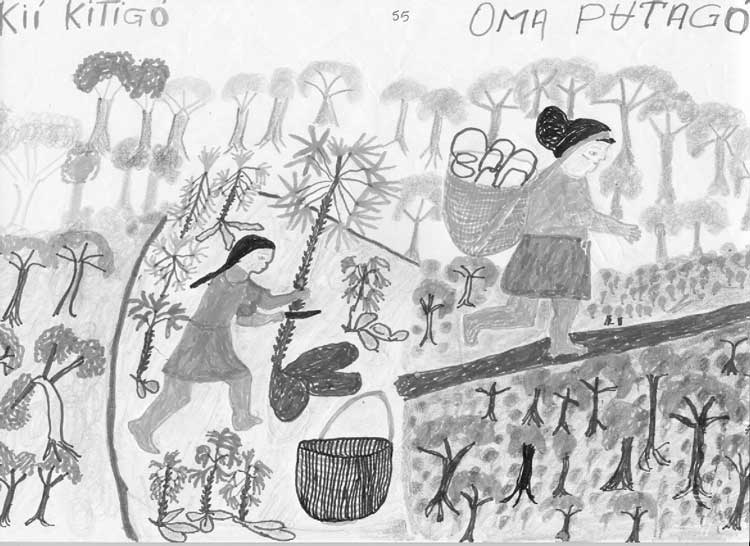

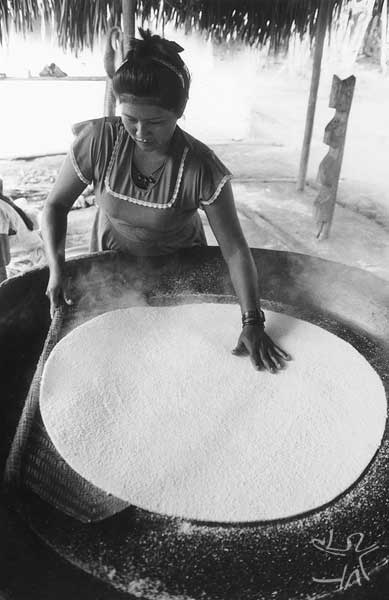

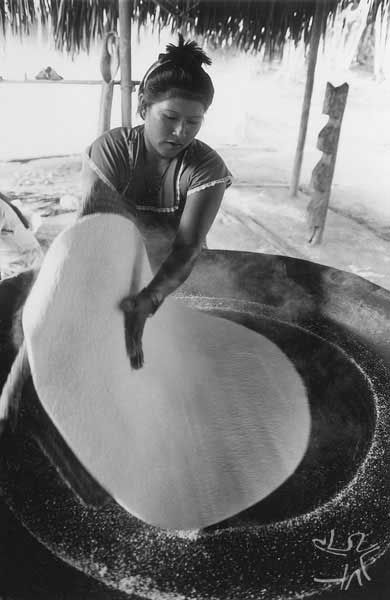

Daily life of the Indians of the river

It’s up to the men to cut down and burn areas of the forest or old secondary growth for the making of the gardens. After that, the work is left to the women, from the choice of the varieties of manioc or other cultivated species to the preparation of food. In the arduous work of producing the different derivatives of manioc(manicuera [sweet manioc juice] , tucupi [seasoning prepared of pepper and manioc juice], tapioca, beiju [bread], mingau [porridge], farinha [manioc flour]), the women spend practically the whole day.

After preparing the first meal, the women go to the garden to harvest, replant and clean out the weeds; sometimes they go to the secondary growth of old gardens, in search of fruits which continue producing after the gardens are abandoned. At home, they scrape manioc, carry water from the river to wash the mass, fetch firewood for the fire, prepare the food and take care of the younger children. From the time they are small, girls help their mothers, at first only by entertaining their little siblings so that the adults can work, and later helping in all chores.

The men usually accompany their wives to the garden, helping them in the weeding and carrying the manioc back home. Often, principally in the older settlements, the gardens are quite distant from the houses, which means that a lot of effort is exerted in carrying the load. Greater male participation is expected when the family is involved in the production of a new stock of manioc flour or a surplus to sell, at which time the men contribute by bringing in greater quantities of firewood to toast the manioc flour. This also happens when a lot of caxiri is made for the great festivals.

The main activity of the men is to contribute with the other part of the diet, fish or game meat. In general, the men go out in their canoes every day or during the night to fish or hunt. This work requires a good knowledge of the river, of the best places to fish, the habits of the fish, and the techniques for fishing. In the areas where the fish are more scarce, a good command of the knowledge and techniques of fishing is fundamental. Pratically all the men have at least one canoe, and great value is placed on having a canoe that is larger and better for longer journeys. Sometimes they go out to hunt on foot, covering great distances in their patient and watchful search for game. When a man is able to bring down a larger animal, such as a tapir or a deer, he sets aside part of its meat for a community meal, to which he invites all the people of his village. The community meals, however, are not restricted to occasions of good and abundant food. Almost every day they take place in the morning. Each woman takes her basket of beiju, a pot of porridge and another with fish and pepperpot. Everyone eats together and chats, taking advantage of the occasion to make decisions of collective interest.

Still on the sexual division of labor, the artwork of the women is traditionally restricted to the production of ceramics and gourds, twining of tucum fibre for string, while the men’s work consists of the production of cerimonial objects and all basketry (except for the carrying baskets made of vines, which are produced by Maku women). Among the “river Indians" there are also other points in common, such as the equipment and techniques employed in daily subsistence activities (agriculture, gathering, fishing and hunting; in daily movements and those of greater distance; in cooking processes and conservation of foods, and so on). For example, the artifacts used in the kitchen are the same all over the area: the tipiti [manioc squeezer], cumatá, sieve and baskets made of arumã; Baniwa manioc scrapers, made on the Içana and distributed throughout the region; fans woven from tucum or arumã strips; besides receptacles for pepper and jiraus [suspended platforms for toasting or storing objects] made with the most diverse kinds of material. The baskets used for transporting manioc, fruits and other roots vary on different rivers of the region: on the Uaupés River basin, the Maku aturás made of woven vines are most prominent, being more resistent and produced in different sizes, according to the age and strength of the user; other types of aturá made from the titica vine are also employed on the Negro and Içana rivers, besides jamaxis and turi baskets.

Specializations and trade

For ecological, sociological and symbolic reasons, there exist in the region specializations in artwork (specialized production of certain artifacts for inter-community trade) that define a formalized network of inter-community trade. The Tukano are known for their wooden benches or stools, the Desana and the Baniwa for their baskets, the latter also for their manioc scrapers, the Kubeo for their funeral masks, the Kotiria (some say) for their manioc squeezers, the Maku for their panpipes, curare and carrying baskets. In the case of the artifacts made from arumã, there are also specialists. On the Tiquié River, the Tuyuka and Bará are outstanding canoe-makers, which is a high priority item for all families and which has a high trade value.

Today many communities also devote a great deal of their time to the making of artwork for sale or trade for industrialized products. Through the Salesian missions, the women have come to spend their time making hammocks, mats, and tucum bags for sale, which they learned to make in the schools with the nuns, or with former students and indigenous teachers who gave classes in the communities.

On the Içana there is at the present time an increase in the production of baskets and trays for sale, many Baniwa women are also participating in this activity. There are other places where specialists in the making of ceramics, ritual stools, and carved objects in Brazilwood (e.g., ritual cigar holders) are found.

Sustainable indigenous development

Having concluded the stage of demarcation and ratification of the Indigenous Lands, the Foirn (Federation of the Indigenous Organizations of the upper Rio Negro) and affiliated associations, with the support of various partnerships, went on to concentrate on the great challenge of elaborating a Regional Program for Sustainable Indigenous Development to be undertaken over the long run for the region of the Upper and Middle Rio Negro, including activities for the protection and fiscalization of the lands, technical training, cultural expression, sustainability and the well-being of the indigenous communities.

Towards this end, a Participative Socioenvironmental Zoning was done, at the request of the Foirn which would give support to the planning of integrated activities in the areas of culture, health, education and productive activities. Still on the question of lands, the Foirn has accompanied the administrative proceedings for the identification, delimitation, demarcation and ratification of the following Indigenous Lands: Marabitanas/Cué-Cué and the Lower Rio Negro, as well as the demarcation and ratification of Balaio.

The Program also includes the implantation of model participative projects in the different sub-regions of the demarcated Indigenous Lands, combining basic sanitation actions, alternative energy, food security, generation of income, health, schools, culture, communication and transportation. Training workshops for indigenous technicians, from the associations and the Foirn have been organized in the communities, covering such topics as the operation of radiophones and outboard motors, monitoring invasions, video documentation, zoning activities, the formulation, presentation, and administration of projects, and others. The Regional Program furthermore seeks to stimulate traditional productive activities which have marketing potential, as well as suppport indigenous initiatives for commercializing goods and services.

In relation to health, the overall situation of the indigenous populations in the region is not favorable, with the recurrence of infecto-parasitici diseases, above all respiratory ailments (among which is tuberculosis), malaria, diarrheias and intestinal parasitoses. Presently the DSEI (Special Indigenous Medical District) of the Rio Negro is coordinated by the Foirn, which has sought to adapt the official assistance model to the variety of socio-cultural and epidemiological situations of the communities. The perspective is that ethical and legal procedures be established that guarentee a balance between medical services and the traditional medicines, besides stimulating the training of indigenous professionals and the exchange of information between researchers, communities, and health professionals. Up to now, more than 200 people have been hired, including middle and upper-level professionals, pof which 90% are indigenous professionals.

Seeking to improve the monitoring of health in the communities, the Foirn has been developing, in partnership with ISA, a nutrition care system. Through the project “Health, Nutrition and Environment on the Rio Tiquié”, an evaluation of the nutritional state of the inhabitants of communities in this region is done through anthropometric measurements made on all children and adolescents (sometimes, also on adults), along with an evaluation of their activities and overall diet. The Project includes the participation of indigenous health agents and the exchange of knowledge and experiences between inhabitants of the Tiquié basin and researchers working in this region (anthropologist, bio-anthropologist, ecologist and agronomist). To publicize information on the research and topics related to health and nutrition, bulletins are produced in Portuguese, Tukano and Tuyuka. Although the research is restricted to the Rio Tiquié, in general, its results could be extended to the entire Upper Rio Negro region.

With regard to education, the middle and upper Rio Negro can be characterized as a region with a high degree of school education, but the schools are not equipped to present a differential concept of indigenous education. To change this situation, the Project for Indigenous Education on the Rio Negro, undertaken by the Foirn, in partnership with the ISA since 1999, has sought to encourage initiatives for reformulating the process of school education implanted in the region since the beginning of the XXth Century by the Salesian Mission. Although the Municipal Secretary for Education has developed a network of primary schools in the local communities, including the hiring of indigenous teachers, the missions continue to have a monopoly over education from the 5th to the 8th grades, which is available only in the mission centres and in the municipal capitol (in state schools but which are run by the Salesians), to which the population of the local communities has been stimulated to migrate.

In contrast, the Education Project seeks to implant a type of school that is adapted to the local realities, that educates people/citizens whose profile is defined by each ethnic group/community, who are involved and interested in the present and in the future of their peoples and lands, seeking political autonomy, control over the administration of the educational process in the short and long run, overcoming discrimination, strengthening the self-esteem of the groups and economic self-sustainability.

At the present time, the project has made possible indigenous schools in three distinct geographical points, covering the population of the Içana basin, the peoples of the Tukano Triangle on the Uaupés and the population of the Rio Negro around the city of São Gabriel da Cachoeira. On the Içana, the Baniwa Coripaco Pamáali Indigenous School, begun in the year 2000, is the first experiment at extending education in the communities to the 5th to 8th grades. On the Upper Rio Tiquié, the Ütapinopona Tuyuka Indigenous School involves five Tuyuka communities, its work emphasizing the language and culture of this ethnic group. In Iauareté, a project is in progress for education and revitalization of the Tariana language, which includes pedagogical workshops for the the preparation of didactic material in this language. This same project of education and stimulation of language and culture is being done with the Kotiria, Desana and Tukano languages among the populations of the Uaupés who speak these languages.

In the area of economic alternatives, a pioneer experience in the Brazilian Amazon has been developed by the Atriart (Associations of the Indigenous Tribes of the upper Tiquié), the ISA and the Foirn since 1999. This is the Pisciculture Project, which develops technologies for reproduction in captivity of species of fish of the region (like the aracu) and the continuous production of young fish to populate the community dams, according to regional ecological and logistical circumstances.

The first breeding station was established in the village of Caruru Cachoeira, on the upper Rio Tiquié, and has involved a group of 15 communities between São Domingos and the Brazil/Colombia border, benefitting around 550 people. With the success of the artificial reproduction of the aracu, resulting from the work of the indigenous team, and the growing number of family fishponds, besides the development of agroforestry systems for feeding the fish, the Project was recognized and approved by the PDPI program (Demonstrative Projects of the Indigenous Peoples), which will provide financial support to its activities until 2005. Continuing this initiative, in 2002 a second breeding station was built in Iauareté, with the support and administration of the Coidi (Coordenating Committee of the Indigenous Organizations of the District of Iauareté). Like the projects in education and Health and Nutrition, this project produces informative bilingual bulletins in the Portuguese, Tuyuka, and Tukano languages which publicize its results and finding associated with this activity.

Another very successful undertaking in the area of economic alternatives is being accomplished by the Baniwa of the Içana River, in one more partnership with the ISA.

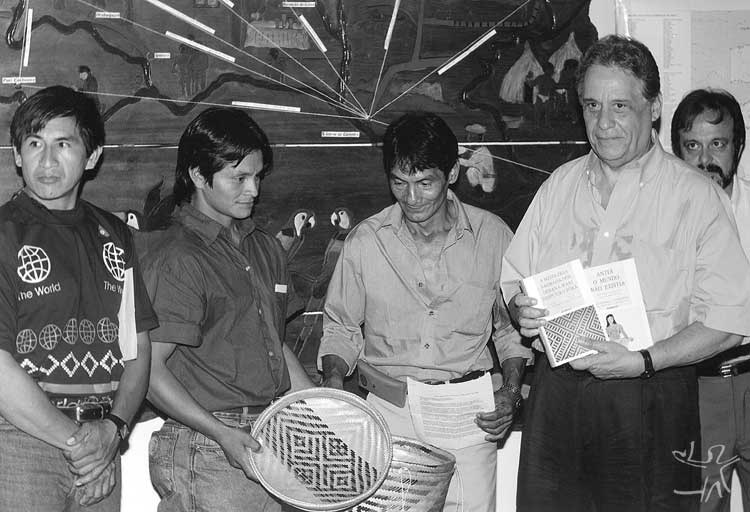

Outstanding artisans of basketwork with arumã fibres, the Indians have created the logo “Baniwa Art” and have been commercializing their production in different markets, notably in the network of Tok&Stok; shops, in the city of São Paulo.

This set of projects, covering various areas, all through the initiative of the Foirn, affiliated associations and communities, has relied on the support of consultants and researchers from various parts of the world. Seeking to intensify the interchange of experiences, specialties, and forms of knowledge, as well as to map out the research that is being done in the region (in the areas of Anthropology, Biology, Ecology, Medicine, Archaeology, Education, Nutrition etc.), two seminars were organized in the years 2000 and 2002, which provided occasions for evaluating what has been produced and for tracing guidelines for future projects, in such a way as to meet the interests not only of the researchers and institutions, but also of the communities studied.

In this sense, the seminars set forth the basic principles for the establishment of procedures in maintaining the relation between Indians and researchers. In the first place, it was recommended that a contract be made between the community (or people, or association) and the person (corporate or not, public or private) responsible for the research, in such a way that the groups researched, or in whose territory the research will be developed, may have control over research procedures and the final destination of the material and derived products. Thus, the researchers must be committed to sharing the benefits derived from the research, whether by means of publicizing in an accessible way the results of their research, or by a share in the financial results resulting from the economic exploitation of whatever products, or any other way in which the research results may be divided with, or returned to, the communities.

Another important victory for the Foirn was an agreement signed in 2001 with the Ministry of Justice to put into effect the project which came to be known as “Citizens’ Window” and which guarantees the Indians their right to obtain basic documents (identity cards, etc.) free of charge. Boats take to the villages the material necessary for emitting documents such as the RG (General Register) and the work card. The indigenous associations are also being benefitted, by getting their documents in legal order. The project also sponsored a course for training indigenous legal agents, which brought together in São Gabriel da Cachoeira 155 representatives of 49 indigenous organizations in order to clarify and discuss fundamental legal questions involving the demarcation and fiscalization of Land, their culture and sustainable development.

Sources of information

- AIKHENVALD, Alexandra Y. Classifiers in Tariana. Anthropological Linguistics, Bloomington : Indiana University, n. 36, p. 407-65, 1994.

(Ed.). Tariana texts and cultural context. Munique : Lincom Europa, 1999. 152 p. (Language of the World/Text Collections, 7)

- ALBERT, Bruce; RAMOS, Alcida Rita (Orgs.). Pacificando o branco : cosmologias do contato no Norte-Amazônico. São Paulo : Unesp ; Imprensa Oficial, 2002. 532 p.

- ALHO, Getúlio Geraldo R. Três Casas Indígenas : pesquisa arquitetônica sobre a casa em três grupos - Tukano, Tapirapé e Ramkokamekra. São Carlos : USP, 1985. 91 p. (Dissertação de Mestrado)

- AMORIM, Rute M. C. História lingüística e consciência étnica dos Warekena. Lume, Florianópolis : UFSC, v. 1, n. 1, p. 45-52, out. 1992.

- ARHEM, Kaj. Ecosofia Makuna. In: CORREA RUBIO, François. La selva humanizada : ecologia alternativa en el tropico húmedo colombiano. Bogotá : Ican/Fondo FEN Colombia/Cerec, 1993. p. 109-26.

. Makuna : portrait of an Amazonian people. Washington : Smithsonian Institution Press, 1998. 172 p.

- ASSIS, Elias C. Patrões e fregueses no Alto Rio Negro : as relações de dominação no discurso do povo Daw. São Gabriel da Cachoeira : Universidade do Amazonas, 2001. (Monografia)

- ASSIS, Lenita de Paula Souza. Do caxiri a cachaça : mudanças nos hábitos de beber do povo Daw no Alto Rio Negro. São Gabriel da Cachoeira : UFAM, 2001. 86 p. (Monografia)

- ATHIAS, Renato. Doença e cura : sistema médico e representação entre os Hupdë-Maku da região do Rio Negro, Amazonas. Horizontes Antropológicos, Porto Alegre : UFRGS, v. 4, n. 9, 1998.

. Hupde-Maku et Tukano : les relations inegales entre deux societés du Uaupes, Amazonie (Bresil). Nanterre : Univ. de Paris X, 1995. (Tese de Doutorado)

- ATHIAS, Renato; BRANDÃO, Maria do Carmo; PAULA, Nilton Cezar de (Orgs.). Saúde indígena em São Gabriel da Cachoeira : uma abordagem antropológica. Recife : Liber Gráfica e Ed., 2002. 232 p.

- BAMONTE, Gerardo. I Macu dell'alto Rio Negro : delimitazione delle aree di distribuzione e breve inchiesta etnografica su alcuni insediamenti del Tiquie. Roma : Univ. Degli Studi di Roma, 1973. 318 p. (Tese de Doutorado)

- BARBOSA, Manuel Marcos; GARCIA, Adriano Manuel. Upiperi Kalili : histórias de antigamente - histórias dos antigos Taliaseri-Phukurana. São Gabriel da Cachoeira : Foirn ; Iauarete : Unirva, 2000. 287 p. (Narradores Indígenas do Rio Negro, 4)

- BEKSTA, Casimiro. A Maloca Tukano-Desana e seu simbolismo. Manaus : Univ. do Amazonas, 1984. 126 p. (Dissertação de Mestrado)

- BIDOU, Patrice. Trois mythes de l'origine du manioc (Nord-Ouest de l'Amazonie). L'Homme, Paris : Ecole des Hautes Etudes en Sciences Soc., n. 140, p. 63-79, 1996.

- BRANDHUBER, Gabriele. Why Tukanoans migrate? Some remarks on conflict on the Upper Rio Negro (Brazil). Journal de la Société des Américanistes, Paris : Société des Américanistes, v. 85, p. 261-80, 1999.

. Zivilisierte Indianer, Moderne Tradition : rezente migrationsprozesse am Oberen Rio Negro, Amazonien - Brasilien. Viena : Universitat Wien, 1998. 155 p. (Dissertação de Mestrado)

- BUCHILLET, Dominique. Contas de vidro, enfeites de branco e "potes de malária". Brasília : UnB, 1995. 24 p. (Série Antropologia, 187)

. Maladie et memoire des origines chez les Desana du Uaupes (Bresil). Paris : Univ. de Paris X, 1983. 264 p. (Tese de Doutorado)

. Pari Cachoeira : o laboratório Tukano do projeto Calha Norte. In: RICARDO, Carlos Alberto (Ed.). Povos Indígenas no Brasil : 1987/88/89/90. São Paulo : Cedi, 1991. p. 107-15. (Aconteceu Especial, 18)

. Perles de verre, parures de blancs et 'pots de paludisme' : epidemiologie et representations Desana des maladies infectueuses (Haut Rio Negro, Bresil). Journal de la Sociétè des Américanistes, Paris : Sociétè des Américanistes, n. 81, p. 181-206, 1995.

. Los poderes del hablar : terapia y agresión chamánica entre los índios Desana del Vaupes brasileiro. In: BASSO, Ellen B.; SHERZER, Joel (Coords.). Las culturas nativas latinoamericanas a traves de su discurso. Quito : Abya-Yala ; Roma : MLAL, 1990. p. 319-54. (Colección 500 Años, 24).

- CABALZAR FILHO, Aloísio. Descendência e aliança no espaço Tuyuka : a noção de nexo regional no noroeste amazônico. Rev. de Antropologia, São Paulo : USP, v. 43, n. 1, p. 61-88, 2000.

. Organização social Tuyuka. São Paulo : USP, 1995. 234 p. (Dissertação de Mestrado)

. O templo profanado : missionários Salesianos e a transformação da maloca Tuyuka. In: WRIGHT, Robin (Org.). Transformando os Deuses : os múltiplos sentidos da conversão entre os povos indígenas no Brasil. Campinas : Unicamp, 1999. p. 363-98.

; RICARDO, Carlos Alberto (Eds.). Povos indígenas do Alto e Médio Rio Negro : uma introdução a diversidade cultural e ambiental do Noroeste da Amazônia brasileira. São Paulo : ISA ; São Gabriel da Cachoeira : Foirn, 1998.

- CABRERA BECERRA, Gabriel. Gentes con cerbatana, canasto y sin canoa. Nomadas, s.l. : s.ed., n. 10, p. 144-55, 1999.

- CABRERA BECERRA, Gabriel; FRANKY CALVO, Carlos Eduardo; MAHECHA RUBIO, Dany. Los nukak : nómadas de la amazonía colombiana. Bogotá : Universidad Nacional de Colombia, 1999. 405 p.

. Nukak, Kakua, Juhup y Hupdu (Maku) : cazadores nomades de la Amazonía Colombiana. In: CORREA RUBIO, François (Ed.). Geografia humana de Colombia : Amazonía-caqueta. Tomo VII, v. II. Bogotá : Univ. Nacional de Colombia, 2000. p. 130-211.

- CARVALHO, Silvia Maria S. de. Jurupari : estudos de mitologia brasileira. São Paulo : Ática, 1979. 392 p.

- CASCUDO, Luís de Câmara Cascudo. Em memória de Stradelli. Manaus : Valer, 2001. 132 p.

- CASTELLANOS, Juan M. (Ed.). Fepaite, nuestro territorio : Atlas Curripaco. Bogotá : Papawiya, Ñewiam, 1992. 60 p.

- CHERNELA, Janet Marion. Tukanoan fishing. Nat. Geogr. Research & Exploration, s.l. : s.ed., v. 10, n. 4, p. 440-57, 1994.

. The Wanano indians of the Brazilian Amazon : a sense of space. Austin : Univ. of Texas Press, 1993. 185 p.

- CLOPATOFSKY, Carlos Alberto Uribe. Etnografia Karapana : un estudio socio-económico de la comunidad. Bogotá : Univ. de los Andes, 1972. 205 p. (Dissertação de Mestrado)

- CORREA RÚBIO, François. Por el camino de la Anaconda remedio : dinámica de la organización social entre los taiwano del Vaupés. Bogotá : Universidad Nacional de Colombia ; Colciencias, 1996. 420 p.

- DUFOUR, Darna Lee. The use of bitter cassaba in Northwestern Amazon. Cassava Newsletter, s.l. : s.ed., v. 8, n. 2, p. 6-7, 12, 1984.

. Uso de la selva tropical por los indígenas Tukano del Vaupés. In: CORREA RUBIO, François. La selva humanizada : ecologia alternativa en el tropico húmedo colombiano. Bogotá : Ican/Fondo FEN Colombia/Cerec, 1993. p. 47-62.

Esta tese foi publicada no final de 1995 pelo MPEG de Belém dentro da Coleção Eduardo Galvão.

- FARIA, Ivani Ferreira de. Território e territorialidades indígenas do Alto Rio Negro. Manaus : EdUA, 2003. 168 p.

- FERNANDES, Américo Castro; FERNANDES, Dorvalino Moura. A mitologia sagrada dos antigos Desana do grupo Wari Dihputiro Põrã. Igarapé Cucura : Unirt ; São Gabriel da Cachoeira : Foirn, 1996. 196 p.

- FERREIRA, Alexandre Rodrigues. Viagem filosófica ao rio Negro. Belém : MPEG, 1983. 775 p.

- FIOCRUZ. Revisitando a Amazônia : expedição aos rios Negro e Branco refaz percurso de Carlos Chagas em 1913. Rio de Janeiro : Fiocruz, 1996. 110 p.

- GARNELO, Luiza; WRIGHT, Robin. Doença, cura e serviços de saúde : representações, praticas e demandas Baniwa. Cadernos de Saúde Pública, Rio de Janeiro : Fiocruz, v. 17, n. 2, p. 273-84, mar./abr. 2001.

- GENTIL, Gabriel dos Santos. Mito Tukano, quatro tempos de antigüidades : histórias proibidas do começo do mundo e dos primeiros seres. v. 1. Frauenfeld : Verlag Im Waldgut, 2000. 216 p.

- GOLDMAN, Irving. The Cubeo : indians of the Northwest Amazon. Urbana : Univ. of Illinois Press, 1979. 316 p.

- HILL, Jonathan; MORAN, Emílio F. Adaptive strategies of Wakuénai peoples to the oligotrophic rain forest of the Rio Negro Basin. In: HAMES, Raymond B.; VICKERS, William T. (Eds.). Adaptive responsees of native amazonians. New York : Academic Press, 1983. p. 113-38.

- HUGH-JONES, Christine. From the milk river : spatial and temporal processes in Northwest Amazonia. Cambridge : Cambridge Univer. Press, 1979. 304 p.

; HUGH-JONES, Stephen. The storage of manioc products and its symbolic importance among the Tukanoans. In: HLADIK, M. et al (Eds.). Food and nutrition in the tropical forest : biocultural interactions. Paris : Unesco, 1994. p. 589-94. (Man in the Biosphere Series, 5)

- HUGH-JONES, Stephen. Clear descent or ambiguous houses? A re-examination of Tukanoan social organization. L'Homme, Paris : École des Hautes Études en Sciences Soc., v. 33, n. 126/128, p. 95-120, abr./dez. 1993.

. Coca, beer, cigars and yage : meals and anti-meals in an amerindian community. In: GOODMAN, D.; LOVEJOY, P. (Eds.). Consuming habits : drugs in history and anthropology. Londres : Routledge, 1995. 47-66 p.

. Lujos de ayer, necesidades de mañana : comercio y trueque en la Amazonia noroccidental. Boletin del Museo del Oro, Bogotá : Museo del Oro, n.21, 1988. p.77-103.

. The palm and the pleiades : initiation and cosmology in Northwest Amazonia. Cambridge : Cambridge Univ. Press, 1979. 332 p.

- INSTITUTO SOCIOAMBIENTAL; FOIRN. Terras indígenas do Alto e Médio Rio Negro. São Paulo : ISA, 2003. (Cartaz-Mapa)

- JACKSON, Jean Elizabeth. Hostile encounters between Nukak and Tukanoans : changing ethnic identity in the Vaupés, Colombia. The Journal of Ethnic Studies, s.l. : s.ed., v. 19, n. 2, p. 17-39, 1991.

- JALLES FILHO, Euphly. Plasticidade e aclimatização fisiológica : o caso das populações indígenas do Alto Rio Negro. São Paulo : USP-IB, 2002. 414 p. (Tese de Doutorado)

- JOURNET, Nicolas. La paix des jardins : structures sociales des indiens curripaco du haut Rio Negro. Paris : Institut d'Ethnologie, 1995.

Originalmente Tese de Doutorado na École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales de Paris com o título: Les jardins de paix : Etude des structures sociales chez les Curripaco du Haut Rio Negro.

- KOCH-GRÜNBERG, Theodor. Dos años entre los indios : viajes por el Noroeste Brasileño 1903/1905. 2 v. Bogotá : Universidad Nacional de Colombia, 1995.

- LABORDE, Alfonso Torres. Mito y cultura entre los Barasana : un grupo indígena Tukano del Vaupés. Bogotá : Univ. de los Andes, 1969. 182 p.

- LAGÓRIO, Eduardo (Coord.). Cem kixti (estórias) Tukano. Brasília : Funai, 1983. 162 p.

- LUZ, Pedro Fernandes Leite da. Estudo comparativo dos complexos ritual e simbólico associados a Banisteriopsis Caapi e espécies congêneres em tribo da língua pano, arawak, tucano e maku. Rio de Janeiro : Museu Nacional/UFRJ, 1996. (Dissertação de Mestrado)

- MacCREAGH, Gordon. White waters and black. Chicago : Univ. of Chicago Press, 1985. 356 p.

- MEIRA, Márcio. Laudo antropológico Área Indígena Baixo Rio Negro. Belém : MPEG, 1991. 183 p.

. O tempo dos patrões : extrativismo da piaçava entre os índios do rio Xié (Alto Rio Negro). Campinas : Unicamp, 1993. 128 p. (Dissertação de Mestrado)

. O tempo dos patrões : extrativismo, comerciantes e história indígena no noroeste da Amazônia. Belém : MPEG, 1994. 27 p. (Cadernos Ciências Humanas, 2)