Ashaninka

- Self-denomination

- Ashenika

- Where they are How many

- AC 1720 (Siasi/Sesai, 2020)

- Peru 97477 (INEI, 2007)

- Linguistic family

- Aruak

The Ashaninka have a long history of resistance, standing up to invaders since the time of the Inca empire until the rubber boom of the nineteenth century and, especially those on the Brazilian side of the border, resisting the encroaches of loggers from the 1980s to today. A people proud of their culture, driven by strong sense of freedom, ready to die in defence of their territory, the Ashaninka are no mere objects of western history. They possess an astonishing capacity to reconcile traditional customs and values with ideas and practices from the western world, such as those to do with socio-environmental sustainability.

Location and population

The area occupied by the Ashaninka extends over a vast territory, from the region of the upper Juruá and the right bank of the Envira river in Brazilian territory to the watersheds of the Andean range in Peru, covering part of the basins of the Urubamba, Ene, Tambo, upper Perene, Pachitea, Pichis and upper Ucayali rivers and the Montaña and Gran Pajonal regions.

The great majority of the Ashaninka live in Peru. Those groups currently inhabiting Brazilian territory also originated in Peru and began the greater part of their migrations to Brazil under pressure from Peruvian caucheiros (latex collectors) in the late 19th century. In Brazil the Ashaninka are found in five distinct and discontinuous Terras Indígenas all located in the upper Juruá region:

- TI Kampa do Rio Amônia, contiguous with the Serra do Divisor National Park, approved and registered with the municipal land registry and the federal property service (unnumbered decree, 23/11/1992), 87,205 hectares in the municipality of Marechal Thaumaturgo;

- TI Kampa do Igarapé Primavera, approved and registered with the municipal land registry and the federal property service (unnumbered decree, 23/04/2001), 21,987 hectares in the municipality of Tarauacá;

- TI Kampa e Isolados do Rio Envira, approved and registered with the municipal land registry and the federal property service (unnumbered decree, 11/12/1998), 232,795 hectares in the municipality of Feijó, also inhabited by Amahuaka groups, historical enemies of the Ashaninka and who avoid contact with indians and non-indians;

- TI Kashinawa/Ashaninka do Rio Breu, approved and registered with the municipal land registry and the federal property service (decree, 30/04/2001), 31,277 hectares, in the municipalities of Marechal Thaumaturgo and Jordão;

- TI Jaminawá/ Envira, approved and registered with the federal property service (unnumbered decree, 10/02/2003), in the munipalities of Feijó and Santa Rosa do Purus, 80,618 hectares; also occupied by Kulina and Jaminawa groups.

A right bank tributary of the Juruá, the Amônia rises in Peruvian territory and offers relatively easy navigation along its course in Brazil. During the rainy season the voyage from the international border to the confluence with the Juruá, located in the municipality of Marechal Thaumaturgo, takes more or less ten hours navigation in a motorized canoe.

Nowadays on the lowlands of the Amônia there are the Alto Juruá Extractive Reserve (right bank) and an Incra resettlement (left bank), whilst the upper part on both banks contains the Terra Indígena Kampa do Rio Amônia.

Census data obtained by anthropologists studying this people show wide variation by author, highlighting the difficulties of arriving at a population total. In Peru the data vary from 10,000 to 50,000 individuals, according to the survey dates and sources. Notwithstanding these hypothetical estimates, all authors stress the importance of the Ashaninka in demographic terms and describe the group as one of the largest native population groups in the Peruvian Amazon and even in the Amazon basin generally.

According to the 1993 census by the Instituto Nacional de Estatística e Informatica (INEI), the Ashaninka people in Peru amount to 51,063 individuals distributed among 359 communities and comprising the most numerous native population of the Peruvian Amazon (Zolezzi 1994: 15). In Brazil surveys carried out by anthropologists, indian support organizations and Funai also show large variations as a result of the lack of registers. To these technical difficulties there should be added the strong migratory trends typical of traditional Ashaninka society, which makes the undertaking of more precise surveys difficult. Despite these difficulties the Pro-Indian Commission of Acre (CPI-AC, an NGO) has estimated the Ashaninka population living in Brazilian territory to be around 869 people.

According to the CPI-AC, the Ashaninka population of the Amônia in 2004 amounted to 472 individuals; in other words, more or less half the Ashaninka living in Brazil. More than 80 percent of this population currently live in the Apiwtxa village or nearby (less than thirty minutes away by motorized canoe). By river the Apiwtxa village is approximately 80 kilometres from Marechal Thaumaturgo and 350 from Cruzeiro do Sul. As the crow flies, the distances are respectively 30 and 180 kilometres. This village was founded in 1995, in the lower portion of the Terra Indígena near to the boundary with the Alto Juruá Extractive Reserve and the Incra settlement.

Also according to CPI-AC data, in 2004 the Terra Indígena do Rio Breu had a population of 114 Ashaninka. At the same time the TI Igarapé Primavera had 21 people and the TI Kampa do Rio Envira 262 individuals.

Name and language

The Ashaninka belong to the Aruak (or Arawak) linguistic family. They constitute the main component of the sub-Andean Aruak group, also comprising the Matsiguenga, Nomatsiguenga and Yanesha (or Amuesha). Despite the existence of dialect differences, the Ashaninka reveal substantial cultural and linguistic homogeneity.

Throughout their history the Ashaninka have been indentified by various names: Ande, Anti, Chuncho, Pilcozone, Tamba, Campari... However they are best known by the term ‘Campa’ or ‘Kampa’. This name is frequently used by anthropologists and missionaries to designate the Ashaninka exclusively or the sub-Andean Aruak generically, with the exception of the Piro and the Amuesha.

Ashenĩka is the self-denomination of the people and may be translated as ‘my relatives’, ‘my people’, ‘my nation’. The term is also used to designate the good spirits who live ‘above’ (henoki).

History in Peru

The history of contact between the Ashaninka and the world of non-indians varies greatly according to region. In Peru some local groups have been in contact since the end of the 16th century as a result of missionary activities during the colonial period, whereas others only came into contact with national society at the end of the 19th century during the caucho and rubber period.

We can separate the history of contact between Ashaninka and brancos into two major periods: the colonial era, characterized mainly by missionary incursion into the Selva Central, and the period of post-independent Peru characterized by the expansion of latex collection, which shaped the different regions of the Amazon, and by the activities of new sectors of non-indian society vis-à-vis indigenous populations. Whilst contact with brancos profoundly altered the lives of the Ashaninka, the history of this people did not begin with the arrival of Europeans.

Trade and war in the Selva Central

The Ashaninka have been present in the Peruvian Selva Central for at least five thousand years. The territory of the sub-Andean Aruak was on the borders of the central part of the Inca empire, whilst in the Amazon region the boundaries between the Aruak and Pano groups were less well defined (both were called Anti by the Inca). In a number of studies the French anthropologist Renard-Cazevitz (1985; 1991; 1992) shows how these three groups established neighbourly relations which, according to circumstances, took on a peaceful or warlike character.

Prior to the arrival of the Spanish there had existed, albeit on a small scale, continuous peacetime trade relations between the lowland peoples and the Inca. The Ashaninka actively participated in this trade. During the summer period delegations of Amazon indians would climb up to the nearest Inca cities with forest products: animals, skins, feathers, wood, cotton, medicinal plants, honey…In exchange for these goods, the Anti returned to their territories with cloth, wool and above all metal objects (silver and gold jewellery, machetes…). Many of these objects would be distributed through kinship networks and inter-Amazon trade. In addition to their economic value, acquiring rare and therefore precious goods was also a means to ensure peace, by establishing political alliances and even kinship links amongst the traders.

Despite such interchanges, periods of peace were interspersed with wars and the empire always sought to conquer the forests and their inhabitants. Despite its superior military apparatus and its continued efforts, the expansionist trends of the Inca empire towards the east were useless and disastrous. Whenever the Inca threat intensified, the ‘peoples of the forest’, warriors experienced in their environment (with steep valleys, forests and rivers difficult to access), mobilized their widespread internal trade networks within the lowlands.

The basis of these inter-Amazon trading and warring networks, which predated the Inca empire, operated until the late 19th century when they progressively collapsed with the intensive penetration of non-indians into the Amazon region during the rubber boom. The Ashaninka, and the sub-Andean Aruak generally, occupied a prominent position in this trade and war system. Their privileged status derived not just from their strategic location between the highlands and the Pano-speaking groups (which enabled them to mobilize the ‘peoples of the forest’ whenever the threats from the Inca or the branco intensified), but also from their control of production of the main product of Amazon trade: salt, called tsiwi among the Ashaninka of the Amônia.

For the ‘peoples of the forest’ salt was a highly sought-after product both for the flavour it gave to food and for its ability to conserve food in the hot and humid climate of the lowlands. Located near the Perene river in Ashaninka territory, the mines in the hills of the Cerro de la Sal constituted both the main source of supply for Amazon peoples and the political, economic and spiritual centre of the sub-Andean Aruak. Although their traditional settlement pattern is one of dispersion, in the proximities of the Cerro de la Sal there arose a greater concentration of different groups: Amuesha, Matsiguenga, Nomatsiguenga and, above all, Ashaninka.

Under this scenario for centuries the Anti blocked any mass penetration by non-Amazonians into their lands, maintaining the frontier between the highlands and lowlands relatively stable.

Colonization and indigenous uprisings

Unlike other indigenous societies in the Amazon region, the Ashaninka have a long history of contact with the world of the brancos, dating from the end of the 16th century. Following their occupation of the coast and the highlands, the Spanish conquered the Inca empire and began their penetration towards the Amazon. The Jesuits Font and Mastrillo were the first to make contact with the Ashaninka in 1595. Exploring the Selva Central from the highland town of Andamarca, the two letters sent by these Jesuits to their superiors constitute the first documented source on the Pilcozone indian group, now identified as being the Ashaninka.

Forty years after the first contact made by the Jesuits, the Franciscans began their evangelizing mission to the indigenous populations of the Selva Central, starting further north near the Cerro de la Sal region. In 1635 Jerónimo Jimenez announced the arrival of the Franciscans by entering Ashaninka territory and founding the mission of Quimiri (the present city of La Merced). In 1637 he organized the first exploratory voyage on the Perene, but met his death in an Ashaninka ambush. In 1648 lured by the myth of Paititi which describes it as a place rich in gold, an expedition of missionaries and adventurers tried to reach Cerro de la Sal, but was similarly decimated in an Ashaninka attack.

Despite succesive defeats, Spanish entradas continued. The breakdown of the native systems of exchange resulting from the establishment of missions in strategic locations can be seen for the first time with the evangelizing enterprise of Biedma, a Franciscan identified as the first explorer of the Peruvian montaña region.

After obtaining authorization in 1671 to undertake new entradas in the Cerro de la Sal region, Biedma organized a first expedition in 1673, reopening the Quimiri mission and establishing that of Santa Cruz de Sonomoro, thereby controlling the main access routes to the highlands. In 1674 Biedma founded the Pichana mission with the intention of controlling native traffic between the Ene and Tambo rivers in the direction of the Cerro de la Sal. Left under the control of Padre Izquierdo, the Ashaninka population of Pichana, lead by the cacique Mangoré and supported by the chiefs of Cerro de la Sal, rose up against the Franciscan administration, which was attempting to prohibit polygamy, and killed the missionaries.

An adept of the use of force to conquer the indians, Biedma died in1687 during another expedition to found a mission on the Tambo. The tragic death of Biedma, probably the victim of the revenge of the Piro who the previous year had been attacked by the Conibo who were accompanying the missionary, practically sealed off the Tambo to non-indian access until the beginning of the 20th century.

A hundred years after the first contacts between the Ashaninka and non-indians, the results of Spanish penetration were practically zero. Efforts by the colonizers continued into the 18th century with the intensification of the pressures on the Cerro de la Sal. In some missions the priests installed forges and presented themselves as the only suppliers of metal tools, as a way of attracting and controlling the native population. Ignored during Biedma’s time, the Franciscan request to the Crown to build forts in the region came to fruition in 1737 with the construction of the first fort at the Santa Cruz de Sonomoro mission.

The major missions were able to group hundreds of indians, but the proportion of mission indians was minimal. Many indians fled abandoning the missions, others preferred to remain isolated from the brancos, while the majority established sporadic contact with the missionaries, generally through a chief, in order to obtain metal tools and other goods. Despite this overall situation, the continuing support of the Franciscans by the Crown, in terms of both armed men and money, increased the level of Spanish pressure on the Selva Central and the growth of the missions caused significant impact on the way of life of the indigenous population, creating the bases for indigenous uprisings. From the indigenous viewpoint, life in the missions was also associated with death and the terrors of disease.

The settlement pattern imposed by the missions implied above all a process of compulsory settlement and the forced co-habitation in multi-ethnic villages of a heterogeneous population characterized by bonds of affinity, but also by internal rivalries and conflicts. This loss of freedom, the essence of Ashaninka life, was felt more sharply with the prohibition of polygamy. As Bodley (1970: 4-5) explains, during the first centuries of the Spanish conquest the role of chiefs determined the success or failure of the missions. Thus while the distribution of goods to the chief ensured a certain level of control over the population, the behaviour of the chiefs constituted a challenge to the Christian ideal. A source of prestige among the chiefs, polygamy was regarded by the Franciscan priests as scandalous social behaviour that represented chaotic and primitive promiscuity.

It is in this context that the indigenous insurrection led by Juan Santos Atahualpa occupies a important place in Peruvian history and merits special attention. Through this movement the indians of the Selva Central, and above all the Ashaninka, regained their political autonomy and the whole of their traditional territory that had been progressively lost to the brancos. Described as an Andean mestiço or a Quechan indian, Atahualpa had received a religious education in Cuzco and had travelled to Europe and Africa (Angola and Congo) with a Jesuit priest. He arrived in Quisopango in the heart of the Gran Pajonal in March 1742 accompanied by a Piro chief. Proclaiming himself the Inca or ‘son of God’, the legitimate heir of the empire conquered by the Spanish, Atahualpa announced his intention to recover his lost kingdom and expel the intruders with the help of his indigenous brothers, united in the struggle against the branco.

With the news of the arrival of the liberating messiah, indigenous messengers were despatched from the Gran Pajonal and spread through the Selva Central and neighbouring highlands. The indians responded to the call and the Franciscan missions were rapidly abandoned. Ashaninka, Amuesha, Piro, Conibo and other groups converged on the Gran Pajonal encouraged in the hope of seeing the son of God. Highland indians joined the movement and a pan-indian uprising had begun in the Selva Central. Juan Santos Atahualpa invited all the Spanish and Africans to leave for the highlands. The ultimatum was turned down and armed conflict became inevitable.

Between 1742 and 1752 confrontations between indians and Spanish troops multiplied, providing the rebels with a series of victories that ensured the political autonomy of the indians of the Peruvian Selva Central and the inviolability of their traditional territories for more than a century. The revolutionary ideals of Atahualpa were not confined to the lowlands; on the contrary he intended to unite all the indians against the non-indians.

During the decades that followed the uprising of Atahualpa and the Anti, the Peruvian Selva Central remained under the control of indians. The Spanish confined themselves to controlling the access routes to the highlands and to protecting their positions in the highlands. On the lower Ucayali the missionaries established trade relations with the riverbank Pano groups, but the territory of the Ashaninka remained inaccessible to brancos. At the independence of Peru in 1822 the Amazon region remained largely unknown, a mysterious and threatening region whose integration was necessary for the consolidation of the new nation state.

The Ashaninka and the rubber economy

The re-conquest of the Peruvian Selva Central progressively took shape, moving from the Chanchamayo region in the direction of the Cerro de la Sal and the Perene. Although a continuation of the moves started by the Spanish in previous centuries, the new Peruvian colonization movement took a somewhat different form. It was mainly guided by economic and political interests and only secondarily by religious or civilizing concerns.

The first move in the re-conquest was a Peruvian military expedition organized in 1847 against the Cerro de la Sal. Despite indigenous resistance, the military accompanied by Andean colonists founded the fort of San Ramón, established new settlements and steadily gained control of Ashaninka foundries.

Colonization of the Chanchamayo valley, the Perene and the Cerro de la Sal was encouraged by the government through policies to facilitate migration of Andean origin and through incentives to foreign immigration.

In 1891 the government granted a concession of 500,000 hectares of land along the Perene river to the Peruvian Corporation. This British company was charged with developing the region, mainly through coffee plantations into which hundreds of Ashaninka were steadily incorporated as labourers.

Displaced towards the Gran Pajonal and the lowlands, or gathered into agricultural colonies, little by little the Ashaninka gave way to the growing presence of whites. By the end of the 19th century Peruvians controlled the Cerro de la Sal and started industrial salt production. With the loss of salt signifying economic dependence, a dramatic story hit the lowlands of the Peruvian Amazon and profoundly altered the way of life of its indigenous populations: the caucho boom.

The search for rubber, a native Amazon species, profoundly changed the history of the region and had dramatic consequences for its indigenous populations. As was the case in Acre, the Peruvian lowlands provided the stage for the decimation of several indigenous peoples. The exploitation of rubber began in the 1870s and affected the Ashaninka in the upper Ucayali region. It is important to note that the principal form of rubber production in this area was caucho (Castilloa elastica) and not seringa (Hevea brasiliensis). Inferior in quality to seringa, caucho is characterized by the itinerant nature of its production, requiring a permanently mobile labour force to go in search of new trees.

Unlike the seringueiro (rubber tapper) settled in the seringal (rubber estate) and walking his trails daily to collect the latex of the hevea, collecting caucho requires felling the tree and implies the permanent territorial expansion of the labour force as the production capacity of each area is successively exhausted. While the methods of extraction are different and the environmental impact is most destructive in the case of caucho, the rubber economy, both seringueira and caucheira, is based on the same economic system: known as aviamento in Brazil or habilitación in Peru.

In both habilitación and aviamento, the entire rubber economy is built around a hierarchical chain of debt that connects the different intermediaries. At its base, in other words in the relationship between the patrão (employer) and the producer, money does not circulate and serves only as an abstract reference for establishing levels of debt, a debt that is permanently rolled over by the acquisition and supply of fresh merchandise in exchange for the rubber produced. The fictitious prices are arbitrarily selected by the patrão with the purpose of keeping his workers under his control through control of a debt that can never be paid off. A modern system of slavery, aviamento binds the seringueiro to the seringal and to the patrão seringalista. In a similar way, by means of never-ending debt habilitación creates a dependency relation between the patrão caucheiro and his workers. Although important, the difference between the extraction of caucho and that of seringa resides basically in the mobility that the caucho system requires. However the economic structure that underpins and guides production of the rubber is generally speaking identical.

The exploitation of caucho in the Peruvian Amazon is associated with the bloodthirsty figures of the major patrões, such as Carlos Scharf or Julio Cesar Araña. The latter ruled an ‘empire’ in the region of Iquitos; however history has elected Carlos Fitzcarraldo as the ‘king of caucho’. Fitzcarraldo retreated to the indians of the Gran Pajonal after being accused of spying for Chile and condemned to death by the Peruvian authorities. Identified by the Ashaninka as the returned ‘messiah’, and more precisely as the personification of an amachénka spirit sent by Pawa (the Ashaninka god), Fitzcarraldo managed to bring under his control several Ashaninka groups, whom he presented with weapons. The Campa were joined by the Piro and some mestiços, constituting a veritable militia that enabled Fitzcarraldo to control caucho production over a vast area. The death of Fitzcarraldo in a shipwreck on the upper Urubamba in 1897 brought to a close the adventures of the person responsible for the bloody raids that marked the history of the region. Caucho extraction led to the decimation of many native populations. As well as exploiting the traditional rivalries between groups, Fitzcarraldo encouraged intra-ethnic attacks among the Ashaninka, breaking the prohibition on internal warfare within the group.

After 1912 the caucho economy suffered a steady decline with the crisis provoked by falling prices on the international market. The raiding expeditions institutionalized by the patrões caucheiros tailed off during the early decades of the 20th century until they finally disappeared. With the advance of Peruvian settlement into the Amazon region, many Ashaninka ended up working in the different economic activities carried out by brancos: ranching, agriculture, coffee, hunting, logging, caucho.

Faced with the violence of the caucho economy, many Ashaninka also took up arms whilst others migrated to the regions of the Brazilian and Bolivian frontiers where protestant and evangelical missions offered some form of protection.

'Gringos' and 'communists'

For many Ashaninka the North American missions that sprung up in the Amazon during the 20th century constituted a form of protection against the patrões caucheiros and slave labour. In 1921 Stahl, a Seventh Day Adventist missionary, established a mission on the upper Perene and announced the Apocalypse and the arrival on Christ on Earth. His messianic movement steadily attracted around two thousand indians from the Perene, Tambo, Pango and Gran Pajonal regions (Bodley 1970: 114).

As the announced event did not take place, little by little the greater part of the Ashaninka abandoned the missionary. Over the following decades the number of missions expanded. Through the Summer Institute of Linguistics, the South American Indians Missions, and above all the Seventh-Day Adventists, the North American missionary presence grew among the Ashaninka, reaching record numbers.

The indigenous messianic tradition was also awakened by the involvement of Ashaninka groups in the Movimiento de Izquierda Revolucionaria (MIR). The arrival of the MIR in 1965 split communities, but some Ashaninka ended up joining the revolutionary forces. The armed struggle was short and severely repressed by the military using extreme violence: villages bombed with napalm, torture, and executions. Following the guidance of a shaman, the Ashaninka saw in Lobatón, the leader of the movement in the region, the return of Itomi Pawa, the son of God, and the hope of a better future (Brown & Fernandez 1991).

In the 1980s revolutionary guerrilla movements, dissidents of the Peruvian left, entered Ashaninka territory once again. Sendero Luminoso (SL), founded in 1969 by Guzman, began its Maoist propaganda in the Selva Central, in competition with the Movimento Revolucionário Tupac Amaru (MRTA), the remnant of the MIR. Fighting amongst themselves for control of the rural population and the cocaine trade which financed their actions, the two movements established armed revolutionary bases against the Peruvian government, which progressively organized the counter insurrection.

The state of war which characterized the Peruvian Amazon at the end of the 1980s and the beginning of the 1990s brought disastrous consequences for the Ashaninka: assassination of leaders, torture, forced indoctrination of children, military training, executions… In 1990 Sendero Luminoso achieved total control over the Ene and the upper Tambo regions and by the following year around ten thousand Ashaninka were living under the control of the guerrilla (Espinosa 1993b: 80-82).

Faced with this state of violence the reactions of the Ashaninka were energetic and various. Some collaborated, others withdrew from the areas of conflict, and many fought with their own weapons, organizing a counter offensive against the ‘communists’ of the MRTA and the SL. Using new methods of political organization in the form of modern indigenous associations, the Ashaninka re-invented old models of warrior confederations, used with success to counter Inca and Spanish expansionism. Facing threats, the political alliance of the sub-Andean Aruak got organized and went to war once again against a common enemy.

History in Brazil

The Ashaninka are currently found in Brazilian territory on the upper Juruá. Originally from Peru and found nowadays along the Amônia, Breu and Envira rivers and the Primavera stream, the history of Ashaninka occupation of this region is however difficult to establish with precision. Information from local history sources is vague and provides few indications about the presence of this people on Brazilian territory.

The French priest Tastevin undertook several voyages on the upper Juruá in the first decades of the 20th century and found Ashaninka groups located in the Contamana foothills on the headwaters of the Juruá-Mirim, a left bank tributary of the upper Juruá. When mapping indigenous groups in Acre on the basis of travellers’ and chroniclers’ reports, Castelo Branco (1950: 8) stated that the Kampa were already circulating in this region at the end of the 17th and the beginning of the 18th centuries.

The population to be found today on the Amônia river derives from several places and is the product of successive migrations. In addition to population movements from Peru to Brazil by means of the upper Juruá or tributaries of the Ucayali, throughout the 20th century there have occurred several Ashaninka migrations from the Envira and Breu rivers in the direction of the Amônia. Similarly, although some Ashaninka families have remained fixed on the Amônia since the 1930s, there are kinship ties linking the Ashaninka of the Amônia to those located both in Peruvian territory and in other Brazilian locations.

According to a hypothesis common to many students of this group, the presence of the Ashaninka on the upper Juruá in Brazil (as well in the Bolivian Madre de Dios region) is the result of the activities of Peruvian caucheiros (latex collectors) who, at the end of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th centuries, brought them from the Ucayali to these border regions. However not all the Ashaninka agree with this version.

The Ashaninka allege that, at the end of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th centuries, the Amônia was also inhabited by Amahuaka indians, traditional enemies and regarded as ‘wild’ indians. For the caucheiros and the rubber estate owners, the presence of the Amahuaka represented a permanent threat to rubber collection and a source of constant concern. Regarded as excellent warriors, Ashaninka served the interests of both Brazilian and Peruvian employers, who strategically exploited the traditional hostilities between both peoples. Armed and encouraged by brancos who offered them trade goods, the Ashaninka decimated the Amahuaka and put them to flight. The Ashaninka currently living on the Amônia did not take part in the attacks on the Amahuaka, but can recall the tales of their elder relatives.

Although the Ashaninka participated in the collection of caucho and the protection of the rubber estates, they did not however become integrated into the extractive rubber economy unlike other indigenous groups in Acre. They did however become involved in the system of aviamento (production credit) which governed commercial dealings in the region.

The lower reaches of the Amônia, in the municipality of Marechal Thaumaturgo as far as the Artur (left bank) and Montevidéu (right bank) streams where the last rubber tappers residence of the former Minas Gerais rubber estate was located, were rich in latex and were progressively occupied by rubber tappers from north-eastern Brazil from the end of the 19th century. In addition to being rich in game, fish and rare woods, the upper Amônia in Brazil, from the streams referred to as far as the international boundary, was characterized by the absence of rubber trees. These upper reaches were little sought after by non-indians prior to the 1970s and the intensification of timber extraction.

The organization of work and population growth in the rubber estates required external labour to supply the estate stores with food and other products, thereby ensuring the permanence of the rubber tappers. The Ashaninka of the Amônia became part of the rubber economy by offering new services to the owners. With the extraction of caucho in progressive decline, the principal activity carried out by the group until the 1970s was to hunt wild animals in exchange for goods, supplying both meat and skins which were highly valued on the Amazon market.

Logging and the struggle for land

Far from urban centres and highways, the Ashaninka did not suffer directly or intensely the effects of the expansion of the ranching and agriculture economy that characterized the ‘second conquest’ of Acre in the 1970s. Although the ‘paulistas’ (the name given to new colonists arriving from southern Brazil) also acquired several rubber estates in the upper Juruá region with a view to transforming them into cattle ranches, the Amônia river remained relatively distant from this expanding frontier, although its margins did not escape being cleared for this type of economic activity.

Although some Ashaninka families went to work for ranch owners, planting swidden gardens or clearing areas for cattle raising, the crisis of rubber collection and the pressures deriving from the search for new resources arrived on the middle and upper Amônia essentially in the form of logging. This activity began in the 1970s and was intensified in the 1980s, increasing levels of contact between the Ashaninka and regional non-indian society.

The abundance of hardwoods, mainly in the part occupied by the Ashaninka, led the Amônia to become known locally as the ‘river of wood’. The intensification of logging in the 1980s, with mechanized extraction and clear cutting, had disastrous consequences for the environment and the native population. Logging activities profoundly affected the social organization and cultural reproduction of the Ashaninka of the Amônia.

From the initial felling to the sale to industry, the logging system on the Amônia involved several types of protagonists: the logger, the middle man, the bosses in Cruzeiro do Sul and the European buyers. The Ashaninka and the non-indian squatters operated at the bottom of this system as simple labour. Their labour power was needed to open forest trails, find and cut the trees into logs which were then rolled down to the streams. This work was generally carried out in the ‘summer’, in other words during the dry season.

According to the Ashaninka, the bosses generally recorded their production in notebooks, but ‘always robbed us’. The indians were swindled both on the length and cubic volume of the wood. Ashaninka affirm that in these transactions a length of mahogany could be exchanged for a kilo of salt or of soap.

Several companies bought timber coming from the Amônia, but Marmude Cameli Limitada was the greatest culprit for the damage to the environment and the Ashaninka population as it took part in all the illegal incursions into the indigenous reserve and the removal of mahogany and cedar on an industrial scale. More than a quarter of the reserve suffered directly or indirectly from intensive logging, profoundly affecting the lives of the indians. The area most affected is located between the Taboca, Revoltoso and Amoninha streams, where three illegal mechanized invasions took place in 1981, 1985 and 1987 opening up a total of 80 kilometres of logging roads in the forest.

The Ashaninka refer to this period as a time of penury and hunger, in contrast to the state of plenty that existed on the upper Amônia when they lived isolated from non-indians. During the logging decade the piyarentsi ritual was frequently invaded by squatters accused of getting the indians drunk on cachaça and of sexually abusing the women. Indigenous music and dance were looked down upon by the brancos who brought their cassette players and imposed their own musical preferences.

Because of the presence of the brancos the frequency of the piyarentsi and the kamarãpi diminished; some Ashaninka also stopped wearing the kushma and started dressing like the local population; the native language was the object of discrimination and many men, constantly called upon to cut timber or to carry out other tasks for the brancos, progressively left off producing their handicrafts, to the extent that some objects produced exclusively by men, such as bows, arrows and headdresses, almost disappeared.

As well as this reduction in their cultural activities, the logging period is also regarded by the Ashaninka as the period of most illness and deaths. The intensive contact with brancos is marked by the multiplication of diseases: influenza, pneumonia, whooping cough, measles, hepatitis, typhoid fever, cholera... Although there are no data that allow an exact assessment of the impact of these diseases on the indigenous population, the Ashaninka affirm that they became endemic, leading to various deaths, affecting above all the children and decimating many families.

Nevertheless, while the indians refer to the ‘time of logging’ as a period of great difficulty and many anxieties, they also emphasize that it was this that lead to the organization of the community and to the union of the group in its struggle for its rights. Within this process the struggle for the demarcation of the reserve is regarded as the decisive moment that allowed them to escape their dependence upon the bosses and to regain their freedom.

From the mid-1980s the growing mobilization of the Ashaninka people of the Amônia connects with the indigenous movement in Acre, marked by an increasing level of conflict between indians and brancos which reached its peak at the end of the 1980s and the beginning of the 1990s.

The ‘time of rights’

Throughout the 20th century the Ashaninka of the Amônia lived a different historical situation from that of the group located on the Envira river. For example, the threat from the Amahuaka was progressively overcome during the rubber period and large scale timber extraction resulted in a level of contact with brancos unknown by the Ashaninka of the Envira, whose territory is further removed from the pressures of national society.

Official indigenous protection activities really started on the Amônia in the mid-1980s, at the height of the logging. To this extent the arrival of Funai is seen as the beginning of a new era: the ‘time of rights’, marked by growing political awareness, the struggle for land and the expulsion of brancos.

In early 1985 a team from the indian protection agency in Brasilia was sent to the area to continue the work of plotting and demarcating the Terra Indígena started in 1978. By a coincidence, the working group arrived in the area at the moment of the second logging invasion. With the return of the team Funai sent alerted the IBDF (the federal forest agency), the predecessor of Ibama, and the Federal Police, who sent representatives to the area, seizing 530 illegally felled trees and fining those responsible.

In 2000 representatives of Marmude Cameli Limitada were sentenced by a lower court to compensate the Ashaninka community of the Amônia river to the amount of around R$ 5.5 million. As well as this sum, the defendants were sentenced to pay around R$ 6 million to the Diffuse Rights Fund ‘for the costs of environmental restoration’. However the defendants appealed the conviction and the case is still waiting to be heard.

Conflicts with squatters

According to the Ashaninka, the period 1987 to 1992 represented a period of great insecurity, whilst at the same time marked by the progressive organization of the indians in defence of their rights, above their right to land, and by the growth of the number of confrontations with non-indian squatters.

In order to escape their economic dependence on the logging bosses, in 1986 the Ashaninka set up a cooperative. A series of prohibitions was put in place: felling trees, hunting for commercial purposes or with dogs, the presence of brancos at the piyarentsi ritual. This increased the hostility of the squatters, who began circulating unfounded rumours about the Pianko family, the main leadership of the cooperative, trying to link it to leftwing guerrilla movements and cocaine trafficking.

The upper Juruá is known to be one of the main drug trade routes. Coming from Colombia or directly from Peru, cocaine enters Brazil by means of the region’s trails and rivers. It is important to distinguish use of the coca leaf from consumption of cocaine. Although derived from the leaf, cocaine undergoes a chemical process that transforms it into the drug. For their part the Ashaninka have traditionally chewed the coca leaf (koka) along with a type of vine (txamero) and a white powder (ishico) extracted from a rock found on the headwaters of small streams and used as a sweetener. Together with tobacco (sheri), the coca is consumed during the piyarentsi and kamarãpi rituals, although its use is frequent and not confined to these occasions. In addition to its cultural dimension (an aspect that is important to emphasize), the Ashaninka also say that chewing coca enables them to fight tiredness and suppress hunger. Amongst the shamans, who in the course of their activities undergo periods of dietary restrictions, the use of coca is indispensible. Growing coca is carried out by each family in the house patio or swidden garden and, although it is used intensively, production is always limited and corresponds only to the needs of each family. In the case of a shaman, the greatest level of production represents only a few dozen plants.

The Ashaninka of the Amônia have always opposed cocaine trafficking on their lands. Indigenous leaders state that they have received numerous offers to encourage the community to plant coca on a large scale or simply to allow the passage of the drug through the area.

In 1990 and 1991 the Ashaninka increased their denunciations to the authorities. Several letters were sent to Funai, Ibama, Incra, the Federal Police and the Office of the Federal Prosecutor. The indians called for measures to speed up the process of demarcating the area and of compensating and resettling the squatters outside the limits of the reserve. They denounced illegal incursions onto the Terra Indígena, illegal logging, hunting with dogs and for commercial ends, drug trafficking and death threats against their leaders and allies... The letters also emphasized the emergency situation and the risk of imminent conflicts between the Ashaninka and the non-indian squatters.

In August 1991 on a trip to Brasília, the Ashaninka leadership were accompanied by the anthropologist Margarete Mendes and the lawyer Ana Valeria Araújo Leitão, a legal adviser at the Núcleo de Direitos Indígenas (NDI, one of the institutions that gave rise to ISA). In the federal capital the group had meetings with the highest authorities of Funai, Ibama, the federal Environment Secretariat, the Office of the Federal Prosecutor and the Federal Police.

The trip to Brasília was decisive in accelerating the process of demarcation and caused enormous impact on the upper Juruá. The death threats increased, coming from those squatters and their families most hostile to the indians. In Brasília, the NDI worked on the procedures for demarcating the area. Via a British diplomat and with the help of the Gaia Foundation, this NGO contacted the Overseas Development Administration (ODA), the international cooperation agency of the British government and obtained the funding needed to carry out the demarcation of the Terra Indígena. The work was finally undertaken between the 3rd and the 23rd of June 1992 with the important participation of the Ashaninka. Following the demarcation, the Terra Indígena Kampa do Rio Amônia, comprising 87,205 hectares was formally registered by the Vice President of Brazil, Itamar Franco, on the 23rd of November 1992.

After being victims of the logging industry, principally in the 1980s when they suffered the incursions of machinery from companies from Cruzeiro do Sul, the Ashaninka of the Amônia were able after years of struggle and great efforts to expel the bosses and the non-indian squatters from their lands. However they still struggle against the repeated incursions by loggers coming mainly from Peru.

Cosmology and shamanism

Among the Ashaninka we can observe the characteristics that make up the shamanistic cosmological systems that exist in the Amazon lowlands: a universe divided into various levels, the existence of an invisible world behind the visible world, the role of the shaman as mediator between these two worlds, and so on. The special nature of the Ashaninka resides perhaps in their extreme dualistic conception of a universe with clearly defined boundaries between good and evil.

According to anthropologist Gerald Weiss, the vertically arranged indigenous universe comprises an indeterminate number of superimposed levels. Thus, working our way upwards, we find successively: Šarinkavéni (‘Hell’), Kivínti (the first subterranean level), Kamavéni (the terrestrial world), Menkóri (the world of the clouds) and other layers that cover the earth and make up the heavens (1969: 81-90). The set of celestial levels is called henóki, although this term is also used to mean the sky, whose proper denomination is Inkite.

According to Weiss, although these levels are inter-related, the inhabitants of each experience their world as solid. Thus for example, to take the case of our Earth (Kamavéni), home to mortals, the visible sky here is merely the ground level of the level immediately above (Menkóri), the greater part of which remains beyond our visual perception. Below the Kamavéni there exist two levels: Kivínki (-1), home to the ‘good spirits’ and Šarinkavéni (-2) which, according to the author, can be considered as the ‘Campa hell’. However Weiss stresses that level -1 is mentioned by only a few Ashaninka and many consider that beneath the earth there exists only Šarinkavéni: the world of the devils.

Ashaninka cosmology becomes complicated when Weiss identifies the inhabitants of the different levels of the universe and tries to explain the role played by each of them, their various manifestations and their relationships with the Ashaninka. In the sky, or more specifically above it (henóki), live the good spirits. This category is called amacénka and also ašanínka, in other words it is taken to be an extension of their own self-denomination as a people.

These spirits are ranked according to the power attributed to their importance in the cosmology. The most powerful are called Tasórenci and are considered to be true gods. The Tasórenci possess the power to transform everything by means of blowing and they make up the Ashaninka pantheon which created and governs the universe. At the top of this hierarchy is Pává (Pawa), the most powerful of the Tasórenci and father of all the creatures of the universe. Although generally invisible to human eyes, some Tasórenci are however able to appear on earth in human form.

The spirits of evil and demons, generically called Kamári, inhabit the lowest level where they live under the supreme authority of Koriošpíri. However these malevolent spirits do not just inhabit Šarinkavéni. Although this first level contains the greatest concentration of these beings and houses the most powerful among them, evil spirits are also found in various places in the world inhabited by mankind. In ‘our’ world, the principal demon is Mankóite, who resides in the riverbanks frequently found along the length of the rivers in Ashaninka territory. He materializes in human form but generally remains invisible. Meeting him presages death. It is interesting to note that, according to Weiss, the Mankóite lives in a similar fashion to the branco (non-indian): their houses contain the same objects; they possess traded goods and so on.

Ashaninka spirituality thus reveals an extremely dualist character. In a hierarchical cosmos headed by Pává, the spirits are generally speaking good (amacénka or ašanínka) or bad (kamári). Each of these manifests their presence in the world inhabited by humans in different ways. The šeripiari (shaman) acts as a mediator between humans and these different layers of the cosmos. With the help of tobacco, coca and kamárampi (ayahuasca), he seeks to communicate with the good spirits and combat the diabolical forces, although he may also put his powers at the service of evil (witchcraft). Thus the plane on which humans live is not inhabited solely by human beings, animals and plants. It reveals itself as a world in a fragile balance, where humans live constantly threatened by the struggle between Good and Evil.

On the Amônia river

The Ashaninka of the Amônia river also recount a vision of a world built around a structure of the universe that is vertically hierarchical and comprised of superimposed layers. The subterranean level is associated with death and evil spirits: kamari. The indians do not talk much about this world inhabited by strange people, some of whom live a life resembling that of non-indians (houses, cars...) and are able to breathe under water. The Ashaninka state that no Ashaninka lives here and that they do not like to think about this dangerous place as this could awaken the evil spirits and summon them up to our world. All agree however that this layer exists and is located ‘below’ (isawiki) our Earth.

Although this world is associated with death and is characterized by some as ‘hell’, it is not always so described. According to Shomõtse, currently the oldest Ashaninka in the Apiwtxa village, ‘hell’ is not located at this subterranean level but is to be found in the heavens, or more precisely ‘above’ (henoki), and not ‘below’ (isawiki). Below exists a ‘great hole full of water boiling as if in a great pan’. The lord of this place is Totõtsi, whose main task is to boil sinful Ashaninka. The presence of ‘hell’ above can also be found in other reports, whilst other informants believe that this place is located below the Earth.

As in the case described by Weiss, the Ashaninka of the Amônia river describe the heavens as being made up of various levels. At the top, in inkite, the all-powerful god Pawa is to be found. On the layer immediately below are the Tasorentsi, who are credited with divine characteristics: “they are like a God, they can pick up anything, blow and transform it into something else”. One level below these, still in henoki, other good spirits can be found who, like the Tasorentsi, are the true ‘children of God’. According to some informants, this layer of the heavens is called Pitsitsiroyki. This is where Pawa chooses from among the Ashaninka those he recognises as his children. According to the Ashaninka of the Amônia, these ‘good spirits’ living in henoki can all be considered to be itome Pawa (children of Pawa) and are called amatxenka or asheninka.

For the Ashaninka of the Amônia, Pawa is described as the god who created the entire universe. At times the Ashaninka refer to him as Paapa (father). Helped directly or indirectly by his children, he created the Earth, the forest, the rivers, the animals, mankind, the sky, the stars, the wind, the rain… In their native mythology many of these creations are in fact transformations of Ashaninka people, children of Pawa, into something else that were made by the blowing of breath. Thus at the time of the creation of the world, the animals, the plants, the stars and certain places or phenomena had human appearance and were, in a general way, children of Pawa. In accordance with the behaviour of these first Ashaninka on the Earth, God and/or the Tasorentsi transformed them into other things good and bad.

Sun and Moon

In Ashaninka mythology, the genders of the Sun and Moon are the opposite of ours, with the Sun being feminine and the Moon masculine. According to Weiss, Pawa was born as the result of a sexual relationship between the Moon and an Ashaninka woman who was burnt to death giving birth to the Sun. Thus the Moon is considered to be the father of Pawa. Before rising to the heavens, Sun and Moon lived for a long time on the Earth.

Moon offered manioc (kaniri) to the Ashaninka who, until that moment, lived only on termites. Nevertheless, despite being the father of Sun and also considered to be a god, Moon had a lower status than Sun as a result of his activities which drew them away from life and brought them closer to death. A cannibal, Moon feeds himself on the dead and the fate of the Ashaninka is to be devoured by him.

This parent-child relationship between the Moon and the Sun causes some problems for the Ashaninka of the Amônia. Kashiri is not always recognised as the father of Pawa, as many informants declare categorically that the latter had always existed and had created everything, including the Moon. The Moon is regarded as ambiguous, on the one hand considered as the god who supplied manioc (kaniri), but on the other regarded as a cannibal who periodically fights with the Sun (eclipses) and associated with the world of the dead.

According to the Ashaninka of the Amônia, after life on Earth, the dead (kamikari) go firstly to the world ‘below’ (isawiki), where they stay for a time. At the time of the new moon, Kashiri swallows them and takes them to Pitsitsiroyki, delivering them to a star. The star is charged with washing, anointing and keeping them until the periodic visit of Pawa who will choose from among the dead those Ashaninka he acknowledges as the legitimate children he wishes to keep close to him.

Non-indians

The hierarchical nature attributed to the Cosmos and the dichotomy between Good and Evil are essential for understanding the place attributed by the Ashaninka to ‘others’ and, above all, to ‘brancos’ (white people). The entire organization of the native Cosmos is based on this structural principle comprising twin elements simultaneously opposite and complementary. Thus whilst the Ashaninka are ideally associated with Good, white people are closely linked to malevolent spirits and the forces of Evil.

This view of the branco (wirakotxa) appears prominently in native mythology. The first wirakotxa that the Ashaninka of the Amônia recount having known was a Spanish-speaker who arose out of a lake as a result of an act of disobedience by the Inka towards his father Pawa, and which upset the order of the universe.

“In the olden days the wirakotxa inhabited a lake. One day Inka went fishing there with another Ashaninka. It was early morning. He heard a chicken at the bottom of the lake and said: “Companion, let’s catch it”. “Let’s not, let’s leave it alone, it’s best not to touch it”. The next day, the same thing. Once again they heard the chicken; they heard a dog bark at the bottom of the lake (...). Then Inka went to see Pawa. “Don’t touch it, my son”. But Inka didn’t listen and went fishing. He heard the chicken really close and heard the dog. “I am going to catch the chicken”. So he dropped his hook baited with banana, a piece like this (...) It brought up the chicken. He cast again and it brought up the dog. Then he heard another noise. He cast more banana and up came the branco. In this way wirakotxa came up to the Earth. Then Pawa became angry and asked: “Why did you go looking for wirakotxa?” “Father, I went to catch chicken and up came wirakotxa”. “I don’t want this branco here together with us. I left him down there but you liked him, so now you can have him. I’m leaving now and you will stay with the wirakotxa and work for him” (Alípio, an Ashaninka living on the Amônia river).

The fact that Inka had fished the chicken and the dog before fishing the branco is taken to be a warning from Pawa to his son that he should stop this unwise behaviour. These animals, brought by white people, were unknown to the Ashaninka who have a very varied collection of myths to explain the appearance of the majority of animals. These were originally Ashaninka who had lost their human appearance and had been turned into animals by Pawa or by the Tasorentsi. However the chicken (txaapa) and the dog (otsitsi) had never been Ashaninka. They arose from the lake where they were the faithful companions of the branco. In some cases the comparison with the dog is used by informants as a generic qualifier for non-indians and/or their behaviour: “ugly as a dog”, “mean as a dog”, “smelly as a dog”…

The appearance of the wirakotxa on the Earth is thus the result the disobedience of Inka towards Pawa, who had initially separated the Ashaninka from non-indians. In the indigenous mythology, the irresponsible behaviour of Inka is yet another example of a long list of mistakes made by the children of Pawa in the earliest days. The sum of these mistakes explains the present situation of the Ashaninka and the imperfections of their world.

The importance of this event is reinforced by myths that consider that it was as a direct consequence of this act that the Creator God rose up to the heavens. Tired of the successive acts of disobedience by his children, Pawa decided to leave them alone on the Earth and to live in the heavens, where he remains to this day enjoying a perfect world. Others say that Pawa remained for a further period on the Earth and tried to build a wall to separate the Ashaninka from the brancos.

Generally speaking, the view that the Ashaninka of the Amônia hold of white people is of a category similar to that of the generic category of evil spirits, the kamari. Like these, the branco is associated with death and disease (matsiarentsi). The indians believe that illness is the result of dangerous beings or the activities of a malevolent shaman using witchcraft. Faced with these dangerous and unknown diseases of non-indians (mãtsiari wirakotxa), the wisdom of the sheripiari is ineffective.

Material culture

The Ashaninka say that they have always had canoes (pitotsi), houses (pãkotsi) and swidden gardens (owãtsi) with several varieties of manioc (kaniri). In the old days their houses were different; they had walls and were built directly on the ground. Nowadays they are built on stilts. Although the non-indian inhabitants of the region also live in raised houses, those of the Ashaninka generally have no walls or interior divisions and are covered with straw, whilst the riverbank wirakotxa use zinc sheeting.

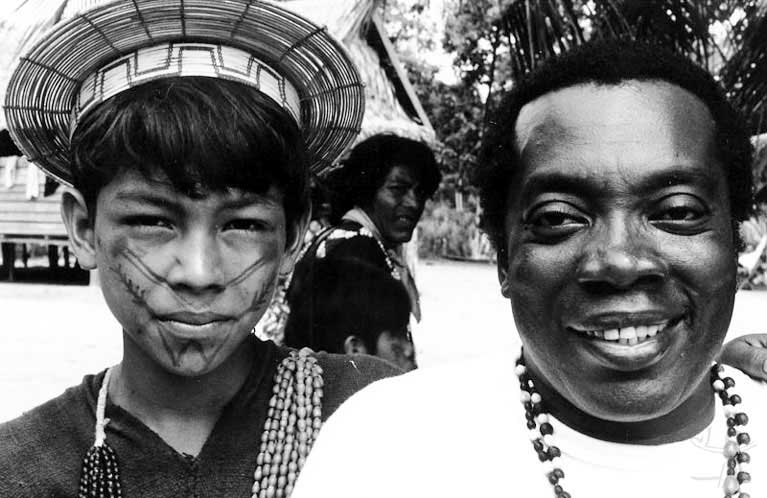

In contrast to other indigenous groups of the South American lowlands, the Ashaninka have always used clothes. The traditional Ashaninka garment, the kushma, constitutes an important element of their ethnic distinctiveness. It is worth noting that the word ‘kushma’ is of Quechua origin and, although the term is also used by the indians, the Ashaninka employ the term kitharentsi, used to refer both to the garment and to the loom and the cloth.

It was the daughters of Pawa who taught the Ashaninka women to weave and to make the garment. For men, the neckline is V-shaped; whilst for women it is U-shaped. The male garment has vertical coloured stripes obtained by dyeing the cotton thread. The women’s kushma has horizontal lines. The motifs made from vegetable dyes are also different. On the male garment they are woven and represent details of animal bodies: a macaw face, the tail of the bushmaster snake, larvae, birds, fish… On the female kushma the designs are painted and represent birds, larvae, fish and, above all, jaguars and snakes… After a certain period of use, both types of garment are dyed using mahogany bark and mud, giving them a brown-black colour. The most important difference between the two types of kushma is that male garments are made in the traditional way with cotton (ãpe) woven on a loom, whilst those of the women are made with manufactured cloth.

The headdress (amatherentsi) is made from the straw of the cocão palm (kõtaki) and decorated with macaw feathers. Whilst its use within the indigenous area may be limited, when preparing their luggage for trips outside the village the chiefs generally make sure to take their headdress along with their kushma.

The txoshiki is a type of necklace made from the seeds of several native species. Worn diagonally around the neck in multiple strands, it is generally decorated with adornments (thatane) that hang down the wearer’s back. These adornments are made from seeds, nut shells or feathers (macaw, parrot, toucan, curassow…). Among the different models, the kenpiro reproduces the design and colours of the snake and is considered by the Ashaninka to be the original and most traditional type of txoshiki.

Amongst Ashaninka musical instruments, the most notable are drums (tãpo) and the sõkari flute. The drum, of varying sizes, is made of cedar wood. The trunk is hollowed out and covered at both ends with the skin of a wild pig, peccary or different species of monkey (black-bearded saki, capuchin, woolly…) or occasionally of a ray. The skin is bound to the wood by a rope of natural fibre (imbaúba). The beat is made with drumsticks made from wood or a monkey bone, generally the femur. The sõkari is a panpipe made up of five bamboo tubes bound together with twine made from cotton thread. The bamboo used is a species that the indians call ‘shawope’ and which they collect on the upper Juruá in Peru. The sõkari is usually played by older men and has a symbolic importance. Informants state that it is used to pay homage to Pawa and is different from other types of flute, such as the showiretsi or the totama which are played at the piyarentsi, simply for dancing.

Rituals

Among the Ashaninka both the drink made from ayuaska and the ritual are called kamarãpi (vomiting, to vomit). The ceremony is always held at night and can last until dawn. An Ashaninka may consume the infusion alone, with his family or invite a group of friends. Generally however the encounters comprise small groups of five or six people. The kamarãpi is characterized by respect and silence, in strong contrast to the animated festivities of the piyarentsi ritual. Communication among participants is minimal and only singing, inspired by the drink, breaks the silence of the night. Unlike the piyarentsi, these sacred songs of the kamarãpi are unaccompanied by any musical instrument. They allow the Ashaninka to communicate with the spirits, thanking and paying homage to Pawa.

The kamarãpi is a gift of Pawa who left them the drink so that the Ashaninka could acquire knowledge and learn how one should live on Earth. The answers to all the questions of mankind are accessible through shamanic learning, acquired through regular and repeated consumption of the drink over the course of many years. The training of a shaman (sheripiari) is however never seen as complete. Whilst his experience confers respect and credibility, he is always learning. It is through kamarãpi that the sheripiari undertakes his journeys to other worlds and acquires the knowledge to treat the misfortunes and illnesses that affect the community.

A cure obtained by means of kamarãpi is only effective for native illnesses, generally caused by witchcraft. The Ashaninka are only able to combat ‘white illnesses’ with the help of manufactured remedies.

The piyarentsi on the other hand has a markedly more festive dimension, although it also possesses economic, political and religious aspects. The ritual constitutes the main avenue for sociability and social interaction among families. During the piyarentsi everything is discussed: marriages, arguments, hunting trips, problems with brancos, projects and so on.

In Apiwtxa the holding of one or more piyarentsi occurs with great frequency, usually at the weekends. The invitation to drink has the character of a social obligation and to refuse is considered an offence. After relying on her husband to dig up the manioc, the wife is solely responsible for preparation of the drink.

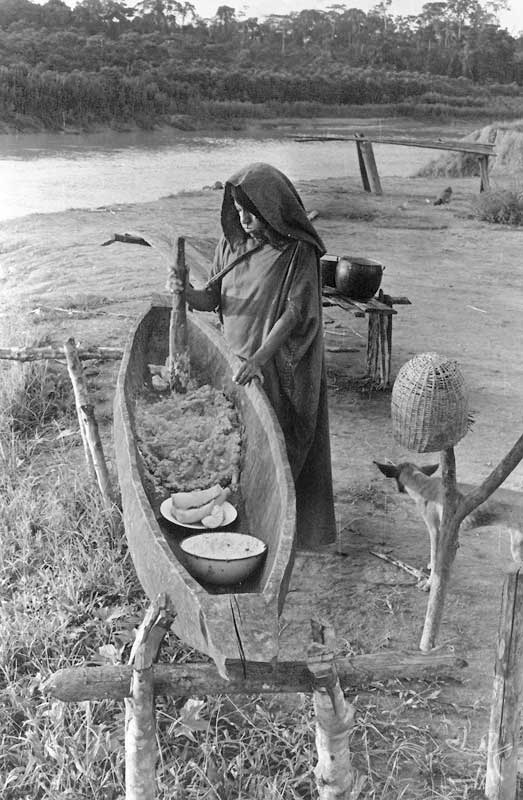

Once peeled, washed and boiled, the manioc (kaniri) is placed in a large wooden trough (intxatonaki) where it is broken up with a wooden tool (intxapatari). A small portion is placed in the mouth and chewed until it acquires the consistency of paste, at which point it is thrown back into the trough. This process is repeated with all the manioc. The trough is then covered with banana leaves and the paste is left to ferment for one to three days. The invitation is generally given by the husband who goes from house to house informing all the other household heads that there will be a piyarentsi.

All the Ashaninka in the village take part in the festivities and consume vast quantities of piyarentsi. On these occasions getting drunk is always the objective and a source of pride. The men demonstrate their physical strength by drinking day and night, going from house to house without sleeping. At the height of their intoxication the Ashaninka play music, dance and laugh. They say that they take part in piyarentsi to pay homage to Pawa, who enjoys seeing his children happy. It was during a piyarentsi ceremony that Pawa called his children together, got them drunk and carried out great transformations before leaving the Earth and ascending to the heavens (Mendes 1991: 108).

Nowadays although contact with national society has given rise to new rituals in the form of community meetings, it is still at the piyarentsi that internal and external politics are strengthened. In addition to discussing the everyday business of the community, at the piyarentsi the Ashaninka discuss their projects and build the awareness of relatives recently arrived from Peru, explaining with pride the history of the community and its organization.

Social organization

The fight against logging and for demarcation of the Terra Indígena led to important transformations in the social and political organization of the Ashaninka of the Amônia. Since the beginning of the 21st century the majority of the indians have altered their settlement patterns, traditionally dispersed along the banks of rivers and stream, and have come together in a community. This change has affected the internal political organization. New institutions such as the cooperative and the school have been created in response to indigenous demands and now occupy a central role in the social life of the indians.

With the creation of the Apiwtxa association the new leaders who emerged during the struggle for demarcation of the land have become the mediators between the Ashaninka and the various indigenous support organizations (Funai, NGOs, the state government, etc.) and are today defining the course of inter-ethnic policies.

These changes in internal politics and the social organization of the Ashaninka of the Amônia are a result of external factors, but also reveal the dynamism and creativity of the Ashaninka society itself which has incorporated these new models by re-interpreting its traditional social structure. Thus for example, the establishment of the Apiwtxa village brought together various families around Antônio Pianko, but the pattern of settlement remained organized into small domestic groups. Similarly the new leaders occupy a privileged position in policies on inter-ethnic contacts, but do not substitute the mechanism of traditional ‘chieftaincy’ whose attributions are also limited and ensure the liberty of each family.

With its traditionally dispersed pattern of settlement, Ashaninka social organization is very flexible. The social unit is the nuclear family, generally composed of the husband, wife and children. Such nuclear families may group themselves around the oldest male (a father or grandfather) constituting a domestic group. These small groupings of houses are generally made up of one to six nuclear families linked by relations of affinity and consanguinity. Domestic groups are marked by a high degree of reciprocity and economic cooperation among the different nuclear families, such as working together in the swidden gardens and the sharing of game. They may be considered as the largest stable political unit in Ashaninka society (Weiss 1969: 40).

A set of domestic groups may come together under the influence of a ‘chief’ in order to form what the Ashaninka call nampitsi and what Mendes defines as a ‘political territory’ (Mendes 1991: 26). The size of the nampitsi is very variable and its boundaries are not always well defined. Domestic groups that make up these political territories may live distant from each other or be grouped into a community. A nampitsi can also coincide with the boundaries of a domestic group or an extended family. Within it, economic cooperation among its groups is minimal, although its members may come together to take part in collective fishing or hunting activities.

The piyarentsi ritual is the main mode of social interaction within the nampitsi. The status of these political territories is extremely flexible, ensuring at the same time the independence and liberty of its components and internal political solidarity. Various factors contribute to the growth, diminution or breakup of a nampitsi: the prestige of the ‘chief’, death, inter-family conflicts, weddings... The traditional ayõpari system of exchange enables the establishment of alliances among different nampitsi, creating greater ethno-political solidarity than could be mobilized on the basis of historic circumstances and which can extend to other indigenous groups.

It should be stressed that the figure of the ‘chief’ is not always found in Ashaninka society and the institution of chieftaincy, when it exists, also reveals a high degree of flexibility. Where he exists, the ‘chief’ can be identified by the term kuraka (or curaca), of Quechan origin, or by the Ashaninka word pinkatsari.

Among the Ashaninka of the Amônia both these definitions are present. However many argue that the pinkatsari is not necessarily a ‘chief’ or kuraka. The pinkatsari is an ãtarite (‘he who knows’), but a warrior (owayiri), a shaman (sheripiari) or an older man renowned for his wisdom and experience can also be termed a pinkatsari without necessarily being a kuraka or ‘chief’. In this sense we can posit the hypothesis that there is no word in the Ashaninka language to designate a ‘chief’, with the Quechan term kuraka being the only unanimously recognized term to identify this function.

Interethnic politics and sustainable development

The cooperative set up by the Ashaninka of the Amônia began operations in 1987 with resources from Funai. In the period November 1989 to February 1990 the Ashaninka also received a donation from the Gaia Foundation (a British environmental NGO) that enabled them to acquire a boat and create a small capital fund. Subsequently they received support from the BNDES (the federal development bank).

At the beginning of the 1990s the Ashaninka started investing in handicraft production. Marketing was helped by the political and media visibility of the Alliance of Forest Peoples at that time. For example, during the Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro in June 1992 Ashaninka handicrafts were sold under the auspices of the Alliance. In the years that followed partnerships were established with the São Paulo store Amoa-Konoya, with the US company Aveda and with Funai’s Artíndia outlets and Moitará project, with the exhibition and marketing of handicrafts in Brasília.

The production and sale of handicrafts currently represents 70 to 80 percent of the capital of the cooperative and is the main economic activity of the Ashaninka. Nevertheless despite the capital obtained from commercial activities, access by the Ashaninka to manufactured goods remains limited to indispensible items: salt, munitions, fishing lines, fish hooks, machetes, soap...

As a means of creating a legal entity able to negotiate and carry out projects, as well as protect the interests of the Ashaninka of the Amônia, the Apiwtxa association was created in 1991 and officially registered in 1993.

The process of affirmation of ethnic identity and of cultural revitalization appears most clearly in the area of education with the notion of ‘differentiated education’ and the project supported since 1997 by the leadership of Apiwtxa to establish a ‘traditional school’. Recently the Ashaninka have also learned to use video to record important moments in the life of the community and their traditional knowledge. School and video, products of western society, have acquired a new significance among the Ashaninka of the Amônia. Non-indian instruments have thus been reinterpreted by the indians and now serve to strengthen cultural traditions and affirm ethnic identity.

Following demarcation of the Terra Indígena in 1992, the Ashaninka of the Amônia also began to carry out a series of sustainable development projects with different indigenous support organizations aiming at identifying alternatives to logging. They began an ambitious programme of environmental protection and restoration and sought to market some of their sustainably produced natural products. Thus within the new context of support to indigenous communities, marked by a growth in concern with the environment, the Ashaninka of the Amônia identified new ways to protect their environment and at the same time collect the benefits of their natural resources.

Together with the CPI (Centro de Pesquisa Indigenista, an NGO that no longer exists), the Ashaninka association developed a project to exploit the oils and essences of palms native to the region. More than fifty products – oils, leaves, pulp, nuts and others – were researched and catalogued during the three year project.

In 1994 under the framework of the Alliance of Forest Peoples, the Ashaninka obtained support from the Embassy of the Netherlands for a monitoring and environmental conservation project that financed the basic infrastructure needed to protect the indigenous reserve against incursions. In 1995 and 1996 the Ashaninka of the Amônia experimented with the collection of seeds of native tree species. Looking towards the reforestation market, the seeds were sent to the Forest Research and Studies Institute (IPEF) of the Luis de Queiroz Higher School of Agriculture (ESALQ) in Piracicaba, São Paulo. Under the terms of the partnership, ESALQ took responsibility for marketing the seeds and, after deducting 25 percent for storage and conservation costs, returned the balance to Apiwtxa on the basis of sales.

In 1999, at the same time as they were collecting murumuru nuts (Astrocaryum palm: A. murumuru) for the Tawaya company, the Ashaninka collected a vine known locally as ‘espera-aí’ (cat’s claw: Uncaria tomertosa). The production of around 25 tons had been to order and was sold to the Biosapiens company which has a representative in Cruzeiro do Sul.

In 2000, in partnership with the Secretariat for Coordination of the Amazon Region of the Ministry of the Environment (SCA-MMA) and the state government of Acre, financed by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), the Apiwtxa community started a beekeeping project.

Also in 2000 the Ashaninka of the Amônia submitted an ambitious project for ‘management of agroforestry systems and environmental restoration of degraded areas’ to the PD/A (Type A Demonstration Projects, one of the sub-programmes of the Pilot Programme for the Protection of the Brazilian Tropical Rainforests – PPG-7).

The concern of the Ashaninka for the environment and the sustainable use of their natural resources is also clear in relation to fauna. After the damage caused by logging and the predatory fishing and hunting practices of non-indian squatters, the Ashaninka on their own initiative started a management plan for fauna in the Terra Indígena. A number of animals, such as fresh-water turtles (shenpiri), almost disappeared from the region during the 1980s.

In 1993 during a community meeting, the Ashaninka discussed management of turtles and decided to ban the collection of eggs and consumption of turtle meat for a period of three years. The turtle population, facing extinction on the Amônia, started increasing again. Under the Management Project for Reproduction of Turtles, carried out in collaboration with Ibama and the NGO SOS Amazônia, the Ashaninka have since 1993 organized an annual celebration with the presence of authorities from the world of the brancos, on the day on which hundreds of turtles are released to repopulate the rivers within the Terra Indígena do Amônea.

The indians also prohibited the use of the timbó poison (waakashi) for fishing carried out on the Amônia and its main streams in order to conserve fish. Like fishing, hunting has also been the target of important initiatives aimed at repopulating the forest with animals traditionally hunted by the Ashaninka. The leaders of Apiwtxa report that since 1992 they have practiced rotation of hunting areas and have created refuge areas for animals.

Thus over the course of the last fifteen years, the Apiwtxa community has received funding from various sources and initiated partnerships to enable the implementation of economic alternatives that respect the environment. The Ashaninka of the Amônia have not only moved ‘towards sustainability’ but are now considered a successful example of the new direction of Amazon policy that seeks to reconcile nature conservation with viable community economic alternatives. It is not by accident that the Ashaninka Francisco da Silva Pianko was made Secretary for the Environment of the municipality of Marechal Taumaturgo in 2001, a post currently occupied by his brother Benki Pianko. Since 2003 Francisco has held the post of Secretary of State for Indigenous Peoples of Acre.

Encroachment by loggers

Following the long struggle during the 1980s against mechanized logging on their lands, the Ashaninka of the Amônia were obliged to face the problem once again at the end of 2000 when Peruvian loggers started invading their territory along the Brazilian-Peruvian border. Despite the tireless resistance of the Ashaninka to this situation, the loggers continue operating until today.

The Ashaninka estimate that around 15 percent of the Terra Indígena along its westernmost boundary has been invaded over the last four years by Peruvian loggers who have opened a series of trails and paths inside the area. As well as illegal logging, Ibama has also identified small encampments of Peruvians along the international boundary and inside the limits of the TI Kampa do Rio Amônia, where temporary laboratories for refining coca base paste appear to be operating.