Arts

Indigenous peoples and the concept of art

Art is a category created by Westerners. And even in the West, what counts as art is far from achieving a consensus. How, then, do we assess the applicability of this term to the visual productions of peoples who do not possess at least a corresponding word in their respective languages?

The topic is complex and, despite the inadequacy of the term, many indigenous works have aroused the sensibility and/or curiosity of the 'white man' since the 16th century, the period during which Europeans first came ashore on the lands inhabited by Amerindians. During this period objects produced by these peoples were collected by kings and noblemen as ‘rare’ specimens of ‘exotic’ and ‘distant’ cultures.

Even today a museological conception of indigenous artefacts remains widespread. For many, these works constitute ‘craftwork,’ considered a minor art, whose artisans merely repeat the same traditional pattern without creating anything new. This perspective ignores the fact that production is not independent of time and cultural dynamics. Moreover, the design of the works results from the confluence of the conceptions and restless questioning of collectives and individuals, though the latter dimension is not foregrounded as in Western art. Fabricated for everyday or ritual use, the production of decorative elements is not indiscriminate but may involve restrictions according to sex, age and social position. It also demands specific knowledge of the materials used, the occasions appropriate for production and so on.

The forms of manipulating pigments, feathers, plant fibres, clay, wood, stone and other materials make Amerindian production unique, differentiating it from Western art just as much as African or Asian productions. However, we are not dealing with an ‘indigenous art’ but ‘indigenous arts,’ since each people possesses particularities in their way of expressing themselves and conferring meaning to their productions.

The substrates for these artistic expressions go beyond the pieces displayed in museums and fairs (baskets, gourds, hammocks, paddles, arrows, benches, masks, sculptures, cloaks, necklaces...) since the human body is also painted, scarified and perforated. The same applies to rocks, trees and other natural formations, without including the crucial presence of dance and music. In all these cases, the aesthetic order is linked to other domains of thought, constituting means of communication – between men and women, between peoples and between worlds – and ways of conceiving, comprehending and reflecting on the social and cosmological order.

In the relations between peoples, the artefacts also act as exchange objects, including trade with ‘Whites.’ In recent years, trade with the surrounding society has provided an alternative income source based on the valorization and divulgation of their cultural production.

Arte Baniwa, a brand created by Baniwa Indians of the Upper Rio Negro (AM), is a successful example of this type of endeavour.

A panorama of diversity

Graphic motif used by the Bakairi of the State of Mato Grosso to make a mask that will be used in the yakuygâde ritual. Rectangular and carved in wood, it represents tutoring spirits related to the aquatic world. Drawing: Odil Apacano, n/d (no date).

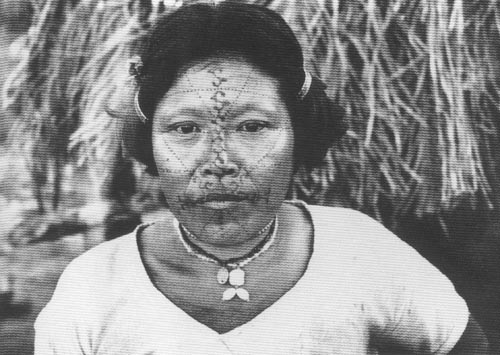

This facial tattoo is part of the second rite of initiation of the Karajá of the States of Mato Grosso and Tocantins, which is held when the girl is approximately 11-years old. Photo: Vladimir Kozak, n/d.

Hilda Tomás do Carmo, a Tikuna Indian from the State of Amazonas, shows the drawing that represents the "celebration of the young woman". Photo: Jussara Gruber,1999.

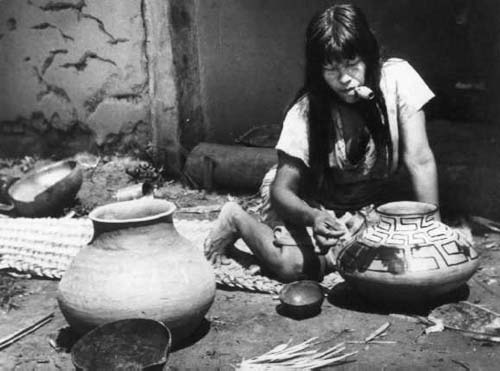

Ceramic is an art form exclusive to women among the Karajá. Photo: Vladimir Kozak, n/d.

Detailed, symmetrical motifs, traced in ink obtained from the mixture of genipap (an orange, edible fruit) with coal dust, still characterize the corporal painting of the Kadiwéu (MS). Photo: Claude Lévi-Strauss, 1935.

Photo: FFLCH/USP Colection, 1935.

Photo: Jussara Gruber, 1979.

The masks of the Matis from the State of Amazonas represent the mariwin spirits, whose traditional role is to beat up children in order to stimulate their beliefs. Photo: Philippe Erikson, n/d.

Among the Xikrin, painting is considered an attribute inherent to the feminine nature. Photo: Michel Pellanders, n/d.

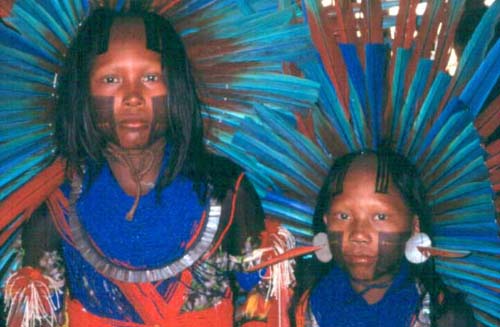

In the nomination ritual of the Xikrin do Cateté, corporal painting and the elaborate feathery art literally transform the girls into birds. Photo: Isabelle Vidal Giannini, 1996.

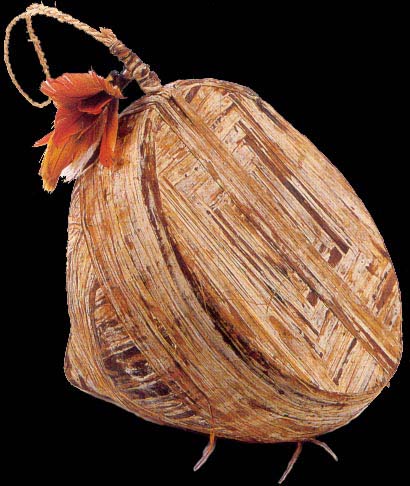

A Baniwa Indian of the Upper Içana River, in the State of Amazonas, puts a label with the logo Arte Baniwa (Baniwa Art) on a 'urutu de arumã', one of the pieces of basketry that is commercialized in São Paulo. Photo: Pedro Martinelli, 2000.

The maruana, a wheel with paintings that represent giant caterpillars, is present in every Wayana house. Drawing: Yeyé. Photo: Lúcia Hussak Van Velthen, 1984.

The motif of this piece of basketry by the Wayana of the State of Pará is the kaikui, the jaguar that symbolically represents the warriors. Photo: Lúcia Hussak Van Velthen, 1984.

The towa, a percussion instrument of the Wari´ (State of Rondônia), is made of clay coated with gum from the rubber tree. Photo: Aparecida Vilaça, 1995.