Introduction

When compared to our society, indigenous peoples display common characteristics. However, seen from closer up, we can note many differences alongside the similarities.

Cultures, languages, forms of social and political organization, rituals, cosmologies, myths, forms of artistic expression, dwellings, ways of relating to the environment, and so on, all vary.

This section on the ways of life of indigenous peoples looks to show both the diversity of the groups cited and the aspects they hold in common.== Shamanism == {{#slideshow id="oslide" imagens="http://img.socioambiental.org/d/769808-1/parakana_9_edit.jpg,http://img.socioambiental.org/d/769811-1/arawete_79_edit.jpg,http://img.socioambiental.org/d/769813-2/IMG_0896_edit.JPG":}}

Photos: various authors, see here by Pedro de Niemeyer Cesarino (2009) ‘Shamanism’ is not something one can reduce to a univocal definition or explanation. Religion, belief, ritual, system of thought, ontology, world configuration: these are just some of the polemical categories that come to mind when we begin to discuss the topic. Generic and misunderstood, the term is employed to designate one of humanity’s most ancient ritual systems, shared by peoples spanning from Asia to the far south of the Americas. ‘Shaman’ apparently derives from the word šamán, used by the Siberian Evenki to designate their ritual specialists. The word is analogous to the Brazilian Portuguese term ‘pajé,’ itself derived from Tupi-Guarani languages where the word is likewise used to refer to such specialists. All Amerindian language across the three continents possess equivalent terms. Shamanism therefore constitutes a common basis to the original peoples of Asia and the Americas, reflecting the fact that the latter continents were occupied by successive migrations from the former. More ancient, shamanism was superimposed by large religions like Buddhism, Confucianism, Taoism, Christianity and Islam. Something similar happens in Brazil where indigenous shamanisms come face-to-face with the Catholic or Protestant faiths. In fact this is a good means of understanding one of the phenomenon’s essential traits: shamanism does not always vanish when confronted by large religious systems. Perhaps since it cannot be comprehended as a ‘religion’ as such, it ends up infiltrating, subverting or surviving the attempts at conversion that, in Brazil for instance, have been pursued since the European invasion. We are dealing, after all, with a particular organization or configuration of the world without any established dogma, set of doctrines, sacred writing, fixed liturgy, body of priests organized around the State or, more importantly, faith in a single deity. Hence shamanism cannot really be defined as a belief. Such absences are especially valid for the indigenous peoples of the South American lowlands, in other words, for those peoples who did not live under the control of state organizations, such as the Inca empire. The mediation performed by Amazonian shamans is more akin to diplomacy, a form of translating and of connecting living humans to the multitude of spirits, the souls of the dead and animals, that populate indigenous cosmologies. In the latter there are no gods as such who embody or have the power to control natural phenomena or for whom temples are built and sacrifices offered (as once found among the Aztecs or Mayans). The entities with which indigenous shamans relate are of another kind. Rather than dispatching a sacrificial victim as an intermediary between gods and humans, shamans travel in person to encounter the spirits and other subjects inhabiting their worlds.

Shaman-less shamanism

Indeed rather than being focused on defined positions, as in the case of priests, shamanism concentrates on processes of transformation and transportation to the dwellings of these other entities. Not by chance, some indigenous societies, like the Parakanã of the Xingu, possess a shaman-less shamanism. In the absence of specific ritual specialists, common people are the ones to encounter people in their dreams and bring back songs to be performed later in the village when the dreamer is awake. It is as though everyone is a little bit shamanic and can, in their own way, make contact with the multitude of invisible entities. A shaman may also suddenly emerge: in a moment of crisis, usually involving a serious illness, a person may begin to establish contact with ‘other people’ who renew his body, replace his blood, introduce magical elements in his flesh and teach him songs. The person is said to have ‘shamanized,’ transformed into another person. From now on he will have ‘another eye’ capable of seeing what is invisible to common people (at least while awake).

All these phenomena are related to the basic composition of the person in indigenous cosmologies. There is always a division between the body and at least two souls or doubles – one that is transformed into a ghost or spectre after death, and another that has a special destiny, celestial in many cases. However, the body is not a physiological substrate in the way western medicine imagines it, but a kind of wrapping, an envelope, skin or clothing that shelters the souls of human appearance. In liminal states such as dreams and illnesses or those induced by the ingestion of psychoactive substances, the soul leaves the person’s body/clothing and wanders freely. On its travels it encounters other villages, spirits, men and women who the eyes ‘of the body’ are unable to see. And it is here that myth and shamanism become intertwined.

What is a myth?

In an interview Claude Lévi-Strauss was asked the following question: “What is a myth?” The anthropologist replied: “‘If you were to ask an American Indian it is extremely likely that he would answer: it is a story from the time when humans and animals were still indistinguishable. This definition seems to me to be very profound.”1 Amerindian mythic narratives are centred on this theme: they depict a time when the general image of the cosmos was ‘human,’ all species shared a generic human form, until some event ruptured this primal state, implanting limits, differences and the problem of invisibility. From then on the animals, frequently due to some error committed during these mythic times, acquired the bodies/clothing of jaguars, tapirs, peccaries or so on, but continued with the same human soul they had always possessed. Humans, for their part, are the only ones whose body remains similar to this generic soul, still shared by all the entities making up the realm we call ‘nature.’ Here we can turn to the words of Yanomami shaman Davi Kopenawa:

“At the beginning of time when our ancestors had not yet transformed into other, we were all human: the macaws, tapirs, peccaries, they were all human. Afterwards these animal ancestors transformed into game. For them, though, we remain the same, we are animals too; we’re the game that lives in houses, while they are inhabitants of the forest. But we, those who remained, we eat them, and they find us terrifying because of our hunger for their flesh.”2

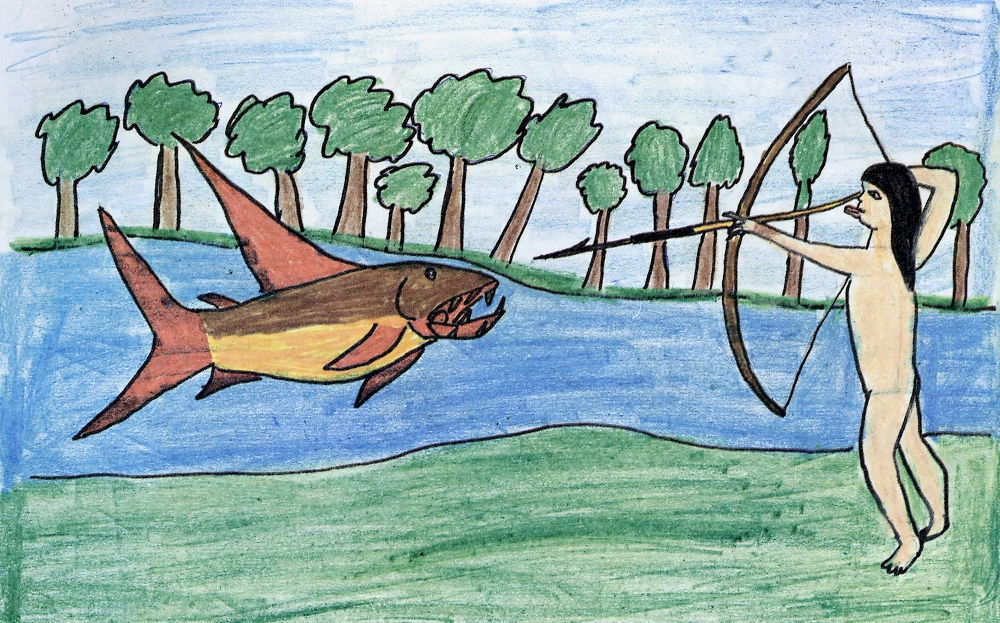

Yet the mythic times are not yet over. For indigenous peoples they continue suspended or parallel to the present. Many animals think of themselves as people, while we see them in their animal bodies/clothing. When a person’s double or soul leaves the body, it can see what was previously hidden: the subaquatic villages and their festivals; the humanoid double or soil of a macaw; a tree that, to altered eyes, reveals itself as a society since the parakeets may conceive of themselves as people and thus as inhabitants of malocas too.

The anthropologist Eduardo Viveiros de Castro formulated this problem through an interesting contrast: indigenous worlds are multinaturalist, they conceive of a multiplicity of natures (the different bodies of the animals) and a unity of culture (the human culture shared by every species). The western world, by contrast, is multiculturalist, imagining a multiplicity of cultures (Chinese, French, etc.) and a single nature. In this conception, animals are radically distinct from humans since they lack a thinking soul analogous to our own and, therefore, a culture. They are like us, though, since they are mammals that share a common nature. Indigenous thought presumes the exact opposite: animals are like us because they conceive of themselves as people and therefore possess a culture (malocas, hammocks, festivals, body painting, headdresses and adornments) similar to what is visible in the villages. But their bodies are other.

And shamanism?

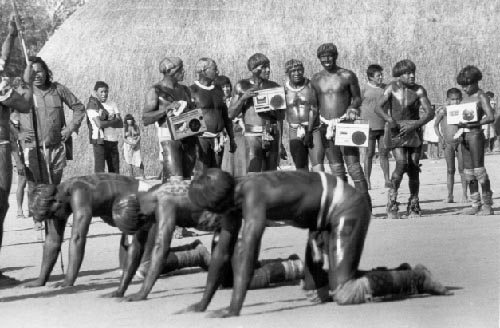

All of this is shamanism, this special constitution of reality and cosmological ethics. Shamans – diplomats or translators as the anthropologist Manuela Carneiro da Cunha suggests – are the people responsible for the risky travelling of souls outside of bodies. When sick, for example, a common man may see the anaconda-people in their houses (which if well he would see as the river) and be seduced by a beautiful anaconda-woman. If this happens, he begins to live there with his underwater family without realizing that, in the other village, his body is debilitating and his condition is worrying his ‘human’ family. He is sick because he is incomplete or empty, since the soul or double is elsewhere with the new anaconda-woman. A shaman must therefore bring the soul back to his body and thereby solve this social problem spread through the cosmos. Situations like this occur frequently in indigenous villages. The shaman is accustomed to these travels. He is already another person; he may have a family with the other-humans, living always between two reference points, journeying among the animal people, the spirits or the souls of the dead. He typically brings back news through his songs and thereby integrates the enormous contingent of invisible entities into the everyday life of the villages. Not coincidentally, some Amazonian Indians say that the shaman “is like a radio.”

One of the biggest mistakes is to imagine that shamanism is a kind of mystic new age religion, or a tradition doomed to disappear in the wake of social transformations and the problematic idea of acculturation. Shamanism – this network or grid of connections between animated principles that live behind visible bodies – is something inherently creative and directed towards alterity. Skilled negotiators of the social multiplicities present since mythic times, shamans know how to translate the news from our world into their own terms. The Maxakali are emblematic of this prowess. Confined in a small area of Minas Gerais now reduced to grassland, deprived of game and access to the landscape in which they once lived, they nonetheless possess an intense and fascinating ritual repertoire. Tuned in, during one festival they made a clay mobile phone, used to communicate with the otter spirits.3== Myths and cosmology ==

Text based on the articles Indigenous myths and cosmologies in Brazil: a short introduction (1992) and Myth, reason, history and society (1995) by Aracy Lopes da Silva

What are myths?

One of the ways in which specialists usually conceive of myths defines them as oral narratives that contain truths deemed fundamental to a people (or social group) and that form a set of stories devoted to recounting the adventures of heroes who lived at the beginning of time (in the time of myth or origins) when everything was created and the world ordered. What is emphasized from this perspective is the narrative form assumed by the myths.

The myth (in the singular) can also be defined as a specific level of language, a special way of thinking and expressing categories, concepts, images and notions connected in stories whose episodes can be easily visualized. The myth, then, is perceived as a way of exercising thought and expressing ideas. What, though, are its distinctive features?

These two definitions agree in terms of their essential aspects. Firstly, both emphasize that myths say something and something important, something to be taken seriously. Secondly, both also highlight the fact that one of the specificities of myth resides in its way of formulating, expressing and ordering ideas and images though which a discourse is constituted and a story narrated. Finally, both definitions suggest a particular relation between myth (or myths), the way of living and thinking and the history of the peoples responsible for its existence.

What do myths speak about?

The indistinction between humans and animals who relate to each other as equals; sky and earth close to each other, almost touching; cosmic journeys, humans who fly, primeval twins, creator insects; subterranean origins; floods, subaquatic human beings; chaos, conquests, transformations... Myths describe the world taking shape, defining places and the characteristics of figures known today.

The mythic themes narrate adventures and primordial beings in a language built through concrete images that can be captured by the senses; situated in a time of origins but referring to the present, containing future prospects and carrying experiences of the past. In other words, myths are complex entities.

Myths are also extremely varied since they are original creations of each group with their own cultural identity, referring to their conditions of existence and their specific cosmovision. But it is equally undeniable that myths form variations of common themes, shared not only locally but, in some cases, universally. Particular and local, universal and essentially human. Perhaps this is where some of the fascination and mystery of myths resides.

In the specific sociocultural universes constituted by each individual indigenous society, the myths are connected to the group’s social life, rituals, history and philosophy with locally developed categories of thought that result in specific ways of conceiving the human person, time, space and the cosmos. This is the level at which the attributes of personal and group identity are defined, what is distinctive and exclusive, and constructed in contrast to what is defined as ‘other:’ nature, the dead, enemies, spirits.

Myth is central to the definition of humanity and its place in the cosmic order in contraposition to other domains – inhabited and controlled by other kinds of beings – seen, sometimes, as different moments of a continuous process of producing life and the world. In this conception of the cosmos, there is order, classification, logical opposition, hierarchy, inclusive and exclusive categories. But there is also movement and a continual play with time, whether to suppress it, enabling living humans to re-encounter the past and their ancestors and origins, or to turn it into an axis of existence itself, destined to be completed and fully constituted after death in the eternal transcendence of the limits of the human condition.

Myth and society

Myths are a place for reflection: they speak of the complex philosophical problems with which human groups must deal. They have multiple layers of meaning and are repeatedly told during the lifetime of individuals who, as they mature socially and intellectually, discover new and unsuspected meanings in the same stories, hidden below the already known and understood layers.

This is how indigenous societies manage to present knowledge, reflections and essential truths in a language that is accessible even to children, who enter into contact with questions whose complexity they gradually come to discover and comprehend.

For all these reasons, myths are difficult to comprehend fully. The truths they express and the conceptions they contain, though touching on questions relevant to all of humanity, are articulated in the values and meanings unique to each society and culture. To understand the latter, therefore, requires a fairly dense knowledge of the sociocultural contexts that serve as reference points for the ideas contained in each myth.

The myths speak about social life and the way in which it is organized and conceived in a particular society. They don't simply reflect the latter: they problematize it, turning it into an object to be questioned and provoking reflection on the reasons for the social order. They can – and indeed very often do – end up reaffirming it (Lévi-Strauss 1976), but this does not unfold in a mechanical form.

Myth and history

Myth, like culture, is alive. At once the product and tool of knowledge and reflection on the world, society and history, it incorporates the constant flux of processes in which social life unfolds as its themes. Myths are collectively elaborated products in which new situations are incorporated and made meaningful (for examples of these processes, see 1993 and Lopes da Silva 1984).

Myths are part of a people’s tradition. However, tradition is continually recreated, otherwise it would lose its meaning and become mere reminiscence rather than the memory of past experiences turned into living reference points for the present and future. Myths, therefore, maintain a relation of exchange with history, recording facts, interpretations, sometimes reducing the new to the known or, inversely, allowing themselves to be swept up by events, transforming with them (Sahlins 1989; Fausto 1992).

Until recently, indigenous societies were understood by scholars to be societies ‘without history.’ These societies were imagined to focus on the mythic past, employing their creativity to remain the same, denying the flow of history, neutralizing transformations and recognizing as processes only those that recompose the model traditionally followed. This was how they were conceived during the early phases of anthropological studies and, due to this fact, were defined as “traditional, sacred and self-enclosed” societies, immune to change. From this viewpoint, indigenous peoples only ‘entered History’ when they first made contact with ‘Whites’ as participants of Western history.

These ideas were later inevitably revised. They were seen to promulgate an ethnocentric viewpoint that impeded the comprehension of native societies in their own terms. We know today (and this is a theme of numerous contemporary research projects) that human cultures develop distinct historical logics as ways of thinking, relating to and experiencing historical processes.

A panorama of diversity

We can turn to some more concrete instances of specifically indigenous ways of conceiving the cosmos and situating oneself within it. The examples that follow are provided here merely as a starting point.

Jê peoples

Among peoples from the Jê linguistic family, the cosmos is conceived to be inhabited by different humanities – subterranean, terrestrial, subaquatic and celestial – who have existed since the beginning of time. The time of origins is that of the indistinction, disorder, cohabitation and interpenetration of these later separate domains. Astral bodies, such as the Sun and Moon, are primordial twins who pursue adventures on earth and leave behind their legacy before departing to their eternal dwelling place. In the Jê myths, there are explicit references to subsistence activities and social practices in general. The origins of social institutions – the naming of individuals, warfare, shamanism – are described in myths and their essence made explicit.

Peoples of the Upper Rio Negro

As a contrasting case we can cite the region of the Upper Rio Negro, Northwest Amazonia, the home of Tukano-speaking peoples. At the beginning of time, mythic ancestors brought the world into existence. The first ancestors emerged from the entrails of a giant ancestral snake, which followed the route of the river. Each ancestor of the various peoples of the region emerged at a precise point on the route, thereby determining their respective territories, their specific characteristics and the hierarchized relationship between them.

In many cosmologies, the relations between humans and other beings are conceived through the idea of predation in a metaphor that symbolically and logically approximates hunting, warfare, sex and commensality. Still on the Upper Rio Negro, the shaman seems to be assigned responsibility for ensuring that flows and volumes of vital energy shared by humans and animals are kept at suitable levels. Any exaggerated culling of animals will lead to a retaliatory response in the form of epidemics and afflictions among humans provoked by the animals’ protector spirits. A vital equilibrium in memories and intimacy with the idea of death are central to the ways in which people experience, appreciate and conduct their day-to-day lives.

Tupi-Guarani peoples

For more than 550 years, non-Indians have produced analyses attempting to comprehend the social practices and cosmological conceptions of the Tupi-Guarani. From the initial shock to Jesuit missionization and the dramatic episodes of the Conquest and finally the systemization of the information from the chroniclers undertaken in the 1940s and 50s, we encounter the constant references to the themes of warfare, cannibalism and the avenging of death through new wars, new deaths and new acts of revenge.

An understanding of these peoples, their societies and their cosmologies, responding to the recent theoretical and methodological maturation of anthropology, reveals – despite the great diversity existing between them both at a sociological level and in terms of the variations between their respective cosmovisions – the centrality of the notion of temporality as an axis on which fundamental notions of the person and cosmos are built. Temporality is allied to the relations of alterity that Tupi-Guarani peoples systematically look to situate beyond the social domain properly speaking, embodied in enemies, spirits, animals, the dead and the divinities.

Sources of information

- FAUSTO, Carlos. “Fragmentos de História e Cultura Tupinambá: da etnologia como instrumento crítico de conhecimento etno-histórico”. In: CARNEIRO DA CUNHA, M. (org.). História dos Índios no Brasil. São Paulo, Cia das Letras/Edusp/SMC, 1992

- GALLOIS, Dominique. Mairi Revisitada. São Paulo, NHII-USP/Fapesp, 1993.

- LALLEMAND, Suzanne. “Cosmogonia”. In: AUGÉ, M. (org.) A construção do mundo. Edições 70, Lisboa, 1978.

- LEACH, Edmund. “O Gênensis enquanto um mito”. In: Edmund Leach (org. Roberto da Matta), Ed. Ática/Grandes Cientistas Sociais/Antropologia 38, 1983, pp. 57-69.

- LÉVI-STRAUSS, C. “A gesta de Asdiwal”. In: Antropologia Estrutural Dois, Ed. Tempo Brasileiro, Rio de Janeiro, 1976.

- LOPES DA SILVA, Aracy. “A expressão mítica da vivência histórica: tempo e espaço na construção da identidade xavante”. In: Anuário Antropológico/82, Tempo Brasileiro/Universidade Federal do Ceará, Rio de Janeiro e Fortaleza, 1984. ------. “Mitos e cosmologias indígenas no Brasil: breve introdução”. In: Índios no Brasil. Grupioni, Luís Donisete Benzi (org.). São Paulo, Secretaria Municipal de Cultura, 1992. ------. “Mito, razão, história e sociedade”. In: LOPES DA SILVA & GRUPIONI (orgs.). A Temática Indígena na Escola. Brasília, MEC/MARI/Unesco, 1995.

- SAHLINS, Marshall. Ilhas de História. São Paulo, Cultrix, 1989.

- VIDAL, Lux. Grafismo Indígena. Estudos de Antropologia Estética. São Paulo, Studio Nobel/Fapesp/Edusp, 1992.

- VIVEIROS DE CASTRO, E. & CARNEIRO DA CUNHA, M. “Vingança e Temporalidade: os Tupinambá”. In: Anuário Antropológico/85, Ed. Universidade de Brasília e Ed. Tempo Brasileiro, Brasília e Rio de Janeiro, 1986.

== Rituals ==

By Renato Sztutman, anthropologist. Professor of the Department of Anthropology of the University of São Paulo, researcher with the Indigenous and Indigenist History Laboratory/NHII-USP and collaborator with ISA.

Introduction

Myths tell how things came to be as they are. They tell how divinities, humans, animals and plants became distinct from one another. Rituals, for their part, take the inverse path to myths. And, not by chance, they frequently work to recount and recreate myths, initiating a kind of return to this time of general indistinction in which divinities, humans, animals and plants communicated among themselves and produced their existence through this interaction.

Indigenous populations believe that this communication and interaction must be undertaken in mediated form and that it is indispensable to the production of persons and society itself. After all, it is from the mythic cosmos that the raw materials for the constitution of persons and society are extracted. Losing sight of this communication and interaction means succumbing to inertia, the remaining in a world without meaning.

Initiation rituals, for example, involve separating neophytes (initiates) from everyday social life and forcing them to pass through a liminal state in which the boundary of the human social world seems to blur. Only by passing through this liminal state can the neophyte return to this world, now transformed.

Funerary rituals, for their part, involve separating the living from the dead, ensuring that the latter return to another, non-human world. Each death places the living involved with it in a state of liminality. Unsurprisingly, therefore, funerary or post-funerary rituals among indigenous peoples very often provide the context for initiating young people.

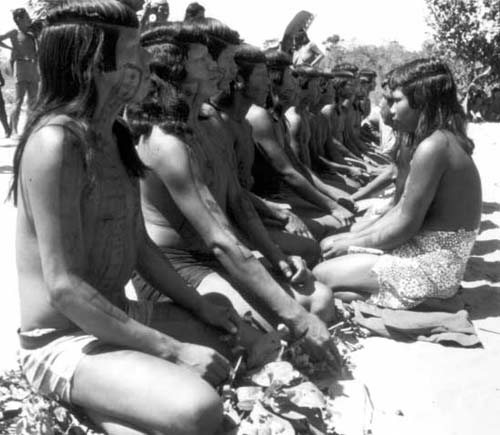

This ritual communication is established among human beings and non-human beings, such as spirits, divinities, the spiritual owners of natural species, subjectivities that inhabit animal bodies and plants, and so on – all endowed with different capacities. But we cannot forget that this communication ends up taking place between individuals of different origin: people from other villages, other territories and even other ethnic groups.

Indigenous rituals are a celebration of differences. Firstly of the differences between the beings inhabiting the cosmos. Humans know that much of what they possess – what we call culture – was not merely ‘invented’ by themselves but taken, during mythic times, from other species and even enemies not seen since the distant past. Indigenous rituals are, moreover, a celebration of differences between human beings themselves, differences without which there would be no exchange or cooperation. And to celebrate these differences an intense network of repayments – above all of food and drink, but also on some occasions songs and artefacts – is set in motion.

[August 2008]

A panorama of diversity

The funerary ritual of the Bororo (State of Mato Grosso) is a special moment of socialization for the young. Not only because many of them are formally initiated then, but also because it is through their participation in the collective chants, dances and hunting and fishing expeditions that they have the opportunity of learning and grasping the wealth of their culture. Photo: Kim-Ir-Sam, 1973.

In the log race, which is associated with several rituals, the Krahó of the State of Tocantins form two groups, called 'halves'. Each of them carries a section of the trunk of a buriti palm (or another tree), whose format, size and decoration may vary. The Krahó are a Timbira group of the Jê linguistic family. Other Timbira and Jê peoples also perform the log race. Photo: Michel Pellanders, 1989.

Among the Kanela (State of Maranhão), a Timbira group, boys are introduced to their age class through several initiation rituals, intended to train them to become warriors. Traditionally, the coming of age of the girls is associated with a maturity belt, required before they get married. Photo: William Crocker, 1975.

In the yãkwa, a ritual performed by the Enawenê-Nawê of the State of Mato Grosso, the villagers, divided in clans, exchange food, chants and dances. The ritual, which lasts several months and has two phases, aims at putting into practice the teachings of the underground spirits, yakairiti. Photo: Vincent Carelli, n/d..

The first initiation of the Karajá boys, from the States of Mato Grosso and Tocantins), takes place when they are around seven or eight years old. It consists of the perforation of the lower lip, which will receive an ornament. The perforation is made with a monkey's collarbone, and is performed in front of the parents. Photo: Cláudia Andujar, n/d.

At the Toototobi hut, of theYanomami of the State of Amazonas, men participate of a session with the hallucinogenic powder, yãkuãna. Very much present in the initiation of the yanomami shamans, it can be taken only with the supervision of older shamans. Photo: Milton Guran, 1991.

Xingu men participate of the huka-huka in the village of the Yawalapiti, in the State of Mato Grosso. This contest is part of the intertribal ritual called kwarúp, performed to honor the dead of the various groups that live in the Upper Xingu River region. Photo: Milton Guran/ 1985.

Os bobos (bobotegi) são personagens que figuram na Festa do navio, realizada pelos Kadiwéu. Este longo ritual remonta aos tempos da Guerra do Paraguai, quando este povo lutou pelo Brasil.

Apesar de desterrados na cidade de São Paulo, os Pankararu, que migraram do estado de Pernambuco, continuam realizando suas cerimônias, cantos e danças.== Arts ==

Indigenous peoples and the concept of art

Art is a category created by Westerners. And even in the West, what counts as art is far from achieving a consensus. How, then, do we assess the applicability of this term to the visual productions of peoples who do not possess at least a corresponding word in their respective languages?

The topic is complex and, despite the inadequacy of the term, many indigenous works have aroused the sensibility and/or curiosity of the 'white man' since the 16th century, the period during which Europeans first came ashore on the lands inhabited by Amerindians. During this period objects produced by these peoples were collected by kings and noblemen as ‘rare’ specimens of ‘exotic’ and ‘distant’ cultures.

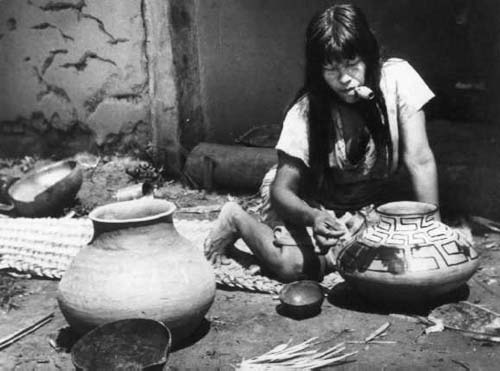

Even today a museological conception of indigenous artefacts remains widespread. For many, these works constitute ‘craftwork,’ considered a minor art, whose artisans merely repeat the same traditional pattern without creating anything new. This perspective ignores the fact that production is not independent of time and cultural dynamics. Moreover, the design of the works results from the confluence of the conceptions and restless questioning of collectives and individuals, though the latter dimension is not foregrounded as in Western art. Fabricated for everyday or ritual use, the production of decorative elements is not indiscriminate but may involve restrictions according to sex, age and social position. It also demands specific knowledge of the materials used, the occasions appropriate for production and so on.

The forms of manipulating pigments, feathers, plant fibres, clay, wood, stone and other materials make Amerindian production unique, differentiating it from Western art just as much as African or Asian productions. However, we are not dealing with an ‘indigenous art’ but ‘indigenous arts,’ since each people possesses particularities in their way of expressing themselves and conferring meaning to their productions.

The substrates for these artistic expressions go beyond the pieces displayed in museums and fairs (baskets, gourds, hammocks, paddles, arrows, benches, masks, sculptures, cloaks, necklaces...) since the human body is also painted, scarified and perforated. The same applies to rocks, trees and other natural formations, without including the crucial presence of dance and music. In all these cases, the aesthetic order is linked to other domains of thought, constituting means of communication – between men and women, between peoples and between worlds – and ways of conceiving, comprehending and reflecting on the social and cosmological order.

In the relations between peoples, the artefacts also act as exchange objects, including trade with ‘Whites.’ In recent years, trade with the surrounding society has provided an alternative income source based on the valorization and divulgation of their cultural production.

Arte Baniwa, a brand created by Baniwa Indians of the Upper Rio Negro (AM), is a successful example of this type of endeavour.

A panorama of diversity

Graphic motif used by the Bakairi of the State of Mato Grosso to make a mask that will be used in the yakuygâde ritual. Rectangular and carved in wood, it represents tutoring spirits related to the aquatic world. Drawing: Odil Apacano, n/d (no date).

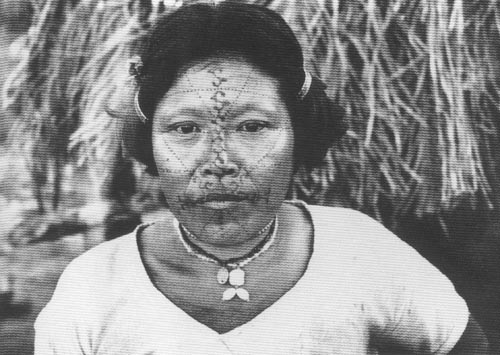

This facial tattoo is part of the second rite of initiation of the Karajá of the States of Mato Grosso and Tocantins, which is held when the girl is approximately 11-years old. Photo: Vladimir Kozak, n/d.

Hilda Tomás do Carmo, a Tikuna Indian from the State of Amazonas, shows the drawing that represents the "celebration of the young woman". Photo: Jussara Gruber,1999.

Ceramic is an art form exclusive to women among the Karajá. Photo: Vladimir Kozak, n/d.

Detailed, symmetrical motifs, traced in ink obtained from the mixture of genipap (an orange, edible fruit) with coal dust, still characterize the corporal painting of the Kadiwéu (MS). Photo: Claude Lévi-Strauss, 1935.

Photo: FFLCH/USP Colection, 1935.

Photo: Jussara Gruber, 1979.

The masks of the Matis from the State of Amazonas represent the mariwin spirits, whose traditional role is to beat up children in order to stimulate their beliefs. Photo: Philippe Erikson, n/d.

Among the Xikrin, painting is considered an attribute inherent to the feminine nature. Photo: Michel Pellanders, n/d.

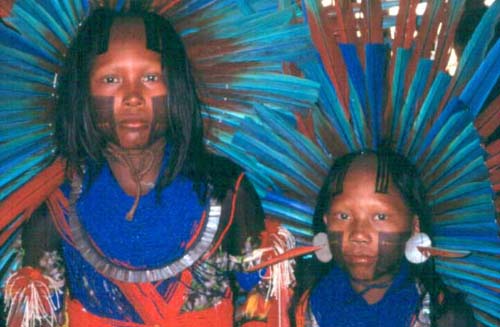

In the nomination ritual of the Xikrin do Cateté, corporal painting and the elaborate feathery art literally transform the girls into birds. Photo: Isabelle Vidal Giannini, 1996.

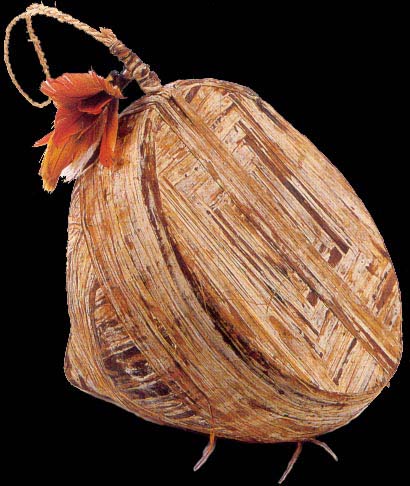

A Baniwa Indian of the Upper Içana River, in the State of Amazonas, puts a label with the logo Arte Baniwa (Baniwa Art) on a 'urutu de arumã', one of the pieces of basketry that is commercialized in São Paulo. Photo: Pedro Martinelli, 2000.

The maruana, a wheel with paintings that represent giant caterpillars, is present in every Wayana house. Drawing: Yeyé. Photo: Lúcia Hussak Van Velthen, 1984.

The motif of this piece of basketry by the Wayana of the State of Pará is the kaikui, the jaguar that symbolically represents the warriors. Photo: Lúcia Hussak Van Velthen, 1984. .

The towa, a percussion instrument of the Wari´ (State of Rondônia), is made of clay coated with gum from the rubber tree. Photo: Aparecida Vilaça, 1995. == Habitations ==

Diversity view

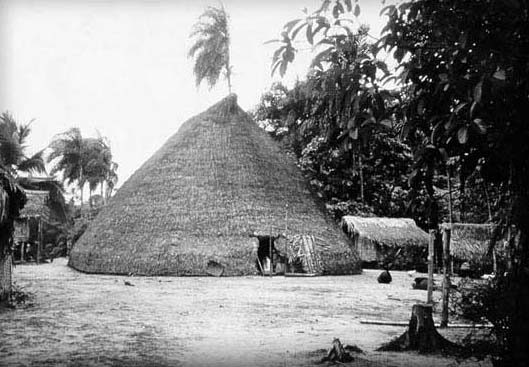

Panará, like the majority of the peoples of the Jê linguistic family, live in round villages near the State limits of Mato Grosso and Pará. The houses are built on the edge of the circle. At the center, the space for political and ritual activities, is where the House of Men is located. Photo: André Villas-Bôas, 1999.

The villages of the Krahó (TO), of the State of Tocantins, people of the Jê linguistic family, follow the Timbira ideal of disposing the houses along a wide circular path, with each of them connected by a radial pathway to the central patio. Foto: Vincent Carelli, 1983.

The Gavião Parkatejê (PA) of the State of Pará speak Oriental Timbira (Jê linguistic family). This is one of their villages, Kaikotore. It is made of 33 brick houses built around a circle with a diameter of approximately de 200 meters. There is a wide path around the circle, in front of the houses, and several radial pathways linking it to the central patio, where all ceremonial activities are held. Photo: Arquivo ISA, 1984.

In a large part of the villages of the present xavante (a Jê people from Eastern Mato Grosso) houses no longer follow the pattern seen in the picture: some combine a brick base and a thatched roof, while others are entirely made of dry grass, but with separated walls and roof. The preference for round houses, set up together in a horseshoe format (a semi-circle of houses opened in the direction of the nearest river), continues among the Xavant.. Photo: Rene Fuerst, 1961.

Among the Marubo, a group that belongs to the Pano linguistic family of the Javari River Valley, in the State of Amazonas, the only inhabited building is the elongated hut, covered with grass and ivorypalm from top to bottom, that is in the center of the village. The buildings around it, raised from the ground with stilts, are used as deposit and are individual properties. Photo: Delvair Montager, 1978.

The Enawenê-Nawê of the State of Mato Grosso, a group that belong to the Aruaque linguistic family, live in villages made of large rectangular houses. A circular house, built more or less in the center, is where their flutes are kept. Rituals and games are held in the central patio. Photo: Ana Lange, 1979.

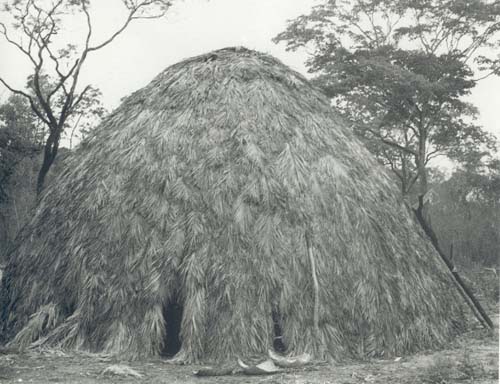

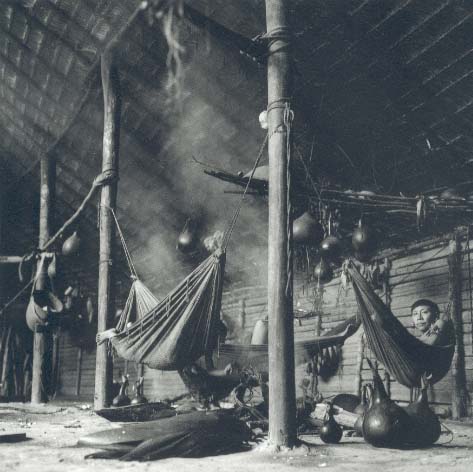

The Eastern and Western Yanomami usually live in a single hut inhabited by several families, such as the one of the photo, of the Tootobi group of the State of Amazonas. Considered an autonomous political and economic entity, it is the home of all the members of the village. Photo: René Fuerst, 1961.

Here, the interior of a collective yanomami house. Photo: René Fuerst, 1961.

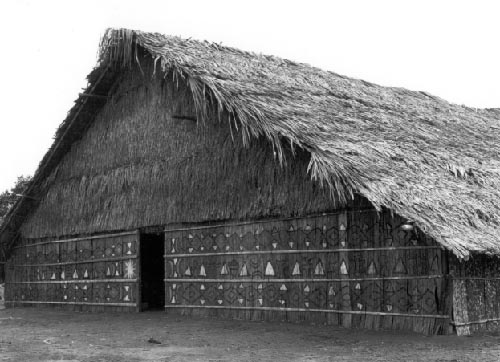

The maloca-museum São João (‘maloca’ is the name of an Indian hut), on the Tiquié River, State of Amazonas, is an example of how the so-called ‘forest Indians’, who spoke languages of the Aruaque and Tukano families, of the regions of the Upper Negro River basin, used to live. It is not just a community house, but also an essential space for the performance of rituals. Its internal design makes it possible for those who live in it to revive, in great ceremonies, the trajectory of mythical ancestors. Photo: Beto Ricardo, 1993.

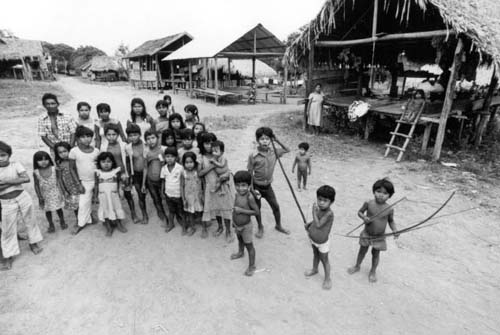

The Palikur of the State of Amapá also belong to the Aruaque linguistic family. Their villages are built facing the river. In the largest of them, Kumenê, the houses are built along two parallel streets. Foto: Vincent Carelli, 1982.

== Indians and the ecology ==

{{#slideshow id="oslide" imagens="http://img.socioambiental.org/d/769659-1/edit_5082183587_5bd627865b_b.jpg,http://img.socioambiental.org/d/769655-1/edit_4X-25.JPG,http://img.socioambiental.org/d/769652-3/edit_4X-18.JPG,http://img.socioambiental.org/d/769661-1/edit_ro__ayanomami.jpg":}}

Foto: various authors, see here Even though they are not 'naturally ecologists', Indigenous people should be seen as historically capable of having managed natural resources in a rather non-destructive way, causing very little environmental disturbances up until the arrival of the European conquerors.

Different conceptions of 'nature'

Those who think of the Indians as 'natural' beings, innate defenders of nature, 'naturalists', are just a step away from seeing them as mere extensions of the environment: for them Indians should be 'preserved' and kept apart from the 'civilized' world.

This vision derives, however, from a conception of nature that is proper to the Western world: the idea of nature as something that should remain untouched, away from human action. What Indigenous peoples themselves have to say about that is very different though.

The conceptions about nature certainly vary considerably according to the Indigenous people we look at. However, if there is anything common to all of them is the fact that nature is always interacting with human actions, it is never untouched.

The Yanomami, for instance, use the word urihi to refer to the 'land-forest': it is a living entity, endowed with a 'vital breath' and with a 'fertility principle' of mythical origin. Urihi is inhabited and enlivened by many spirits, among them the spirits of the Yanomami shamans, who are also its guardians.

The survival of human beings and the preservation of social life in what refers, for example, to obtaining food and protection against diseases, depends on the relationship with these forest spirits. Thus for the Yanomami nature is a stage from which human action is not separated.

Partners of environmental preservation

Even though they are not 'naturally ecologists', Indians are conscious of their dependence - not just physical, but especially cosmological - of the environment. Because of this, they use ways of stewardship of natural resources that have proved to be essential for the preservation of Brazil's natural forest cover.

That is particularly noticeable in the regions where deforestation has been advancing at high rates, such as in the States of Mato Grosso and Rondônia and in the Southern part of the State of Pará. In a survey carried out by INPE (Instituto Nacional de Pesquisas Espaciais - National Institute for Space Research), for instance, Indigenous Lands appear as veritable oasis of forests.

It is true that many Indigenous peoples, such as the Suruí, the Cinta-Larga and the Kayapó, have become actively involved in the predatory ways of exploitation of natural resources that take place in the Amazon Region nowadays by making alliances especially with timber companies. However, it must be recognized that they did so while submitted to concrete, continuos, illegal pressures, and as minority partners in these businesses.

Today and in the future it is necessary to seek mechanisms for maximizing the chances of the Indians solve in their favor the problem of their control over extensive lands with low demographic occupation. One such mechanism is the still incipient combination of Indigenous projects with non-Indian strategies for the sustainable use of natural resources, be them public or private.== Interrelations ==

Foto: Beto Ricardo, 2002

Introduction

Indigenous societies have never been in a state of complete isolation, for even before having relations with Brazilian society they have always related among themselves. In many regions and in many ways, different peoples interrelated through wars, exchange of objects, marriages, invitations for ceremonies and rituals etc.

In spite of being transformed with time, these interrelations have not ceased today. They may take place among a small group of neighboring peoples or extend through a vast region. In some cases, they form very complex exchange networks, in which each society has a specialized role. In others, the relations occur only occasionally.

Waiwai

The Waiwai, located in the Northern part of the State of Pará and in the State of Roraima, have always maintained relations of various natures - matrimonial, commercial and ceremonial - with neighboring populations. So much so that today, after the intensification of contacts with non-Indians, they live with other peoples, among them the Katuena, the Xereu and the Hixkaryana. In the Waiwai communities, although at certain times everyone considers herself/himself Waiwai, there are groups that make a point in clearly marking their difference from the others; when necessary, this may mean even the adoption of a posture of rivalry vis-à-vis others.

Upper Negro River

The region of the Upper Negro River has a vast network of relations connecting the various peoples that live there. It is a rule in some of these societies that a man has to marry a woman from another group, who must necessarily speak a different language. Thus the Tukano, the Arapasso, the Desana, the Tariana, the Tuyuka, among so many others, cannot be considered closed groups, but rather units always open and prone to exchanges.

Relations among the groups of the Upper Negro River do not have only the aspect of an alliance. They also reveal a complex hierarchy system. Those considered ‘river Indians’ – that is, who live on navigable regions and generally speak languages of the Tukano or Aruaque families –, marry among themselves, whereas the ‘forest Indians’, who generally speak Maku languages and live at a distance from the large rivers, are marginalized by the others.

‘River Indians’ not only do not marry the Maku but also refuse to learn their language, because they do not follow the correct patterns of residence and because they marry people who speak their own language, something they consider absurd. Both groups nevertheless maintain constant relations: for example, ‘river Indians’ exchange fish and cassava for meat and services from the Maku.

Upper Xingu River

Home of societies of the Jê, Tupi, Caribe, Aruaque and Trumai languages, the region of the Upper Xingu River is where the most intense interrelations among different Indigenous peoples take place in Brazil.

In the Upper Xingu, old conflicts have given way to peaceful intertribal relations, which includes exchanges of objects and rituals. As anthropologist Eduardo Galvão pointed out, at the time of the creation of the Xingu Indigenous Park (early 1960’s), the different peoples living there ended up specializing themselves in the production or extraction of a given item in order to participate in the exchange network. Thus the Waujá made ceramics; the Kamayurá, bows made of black wood; the Kuikuro and the Kalapalo snail necklaces, and so on.

To this day, it is the rituals that provide a common language to all of them. In the kwarúp, a recently deceased chief is honored, and the homage is extended to other well-liked dead. The yawarí is performed to honor those who have been dead for a while, and also for initiating young men. Both rituals strengthen the links that exist among the various peoples, marking in a symbolic way the opposition between warring ferocity (the guests simulate an attack against host village) and regulated reciprocity (exchange of objects and services).