Ye'kwana

- Self-denomination

- Where they are How many

- Linguistic family

The Ye'kuana, ancient travelers in Amazonia, in the forest and the city, demonstrate how different spaces both within and outside their traditional territory can become articulated, thus creating a kind of dynamic which, far from threatening the preservation of their identity, can actually be favorable to the creation and maintenance of support networks, economic exchanges as well as of information and social and economic projects.

Name and language

A people of the Carib language family, linguistically and culturally different from their Yanomami neighbors, they are also known in Brazil as Maiongong. When the Ye’kuana wish to refer to themselves, they use the word So’to, which can be translated as "people", "person". "Ye’kuana", in turn, can be translated as "canoe people" or even "people of the branch in the river".

Population and location

The Ye´kuana population in Brazil in the year 2000 was around 430 people, divided amongst three communities located on the banks of the Auaris and Uraricoera rivers, in the northwest of the state of Roraima, on the border with Venezuela. Most of this ethnic group lives in Venezuelan territory, where its population is upwards of 4,800 people (Rodriguez and Sarmiento, 2000).

The Ye’kuana community of Auaris is the largest in Brazil, with around 330 people (in the year 2000). Besides Auaris, there is a small community on the upper Auaris River known as Pedra Branca, about ten hours away by boat and trail, and a third community on the Uraricoera River, known as Waikas. The last mentioned has been in existence since the 1980s and had about 80 people in 2003. In contrast with Auaris, this is a region which is abundant in fish and game.

According to researchers who have worked in the area, the Ye’kuana are supposed to have settled on Brazilian lands more than a century ago. But the traditional leaders of Auaris say that the Ye’kuana often visited the region long before they decided to build their houses and settle there. It was a hunting area and a region which they passed through to get to the Uraricoera River, to its islands, and later to the Rio Branco, and then to Boa Vista, the capitol of Roraima.

The mythological map of the Ye’kuana, published in the 1970s by De Civrieux, demonstrates that places such as the Island of Maracá (on the Uraricoera River) are part of the topographical landmarks of the mythology of these people. The Auaris region is an area of difficult access due to the rapids and waterfalls, and is about 450 kilometers away from the capitol of Roraima.

Today, the Ye’kuana and the Sanuma (Yanomami subgroup) live in the Auaris region. These two ethnic groups are part of a social network which includes different communities located on both sides of the border. In Brazil, the region of the Auaris River and a good part of the region of the Uraricoera River were demarcated in the 1990s, as Yanomami Indian Land (a total of 9,664,975 hectares, located in the states of Roraima and Amazonas). The three Ye’kuana communities are included in this area.

History of contact

In their oral history, the Ye’kuana remember their brutal contacts with the Spaniards during the 18th Century. In the beginning they were allies, then they were obliged to work on the construction of military forts in their territory and were coerced into converting to Catholicism when Capuchin and Franciscan missionaries arrived in the region on the order of the Crown. Besides refusing to convert, the Ye’kuana organized a rebellion against the Spaniards in 1776.

By the beginning of the 20th Century, another invasion deeply marked the history of contact with the Ye´kuana, this time by the exploiters of rubber. The Ye’kuana in Brazil still have memories of these experiences, as well as the dispute for territory which this group went through in the past, above all with the Sanumá. According to the anthropologist Alcida Ramos:

"One can still hear from the mature [Maiongong] men stories which they in turn heard from their ancestors about the imprisonment of whole villages for slave labor, the long lines of chained-up Maiongong who were taken to the rubber camps, stories of the times when the extractivist industries were mounted on the backs of the enslaved Indians. The Maiongong lost a good part of their population, they learned Portuguese and Spanish, they acquired rifles and recovered their pride as great housebuilders and canoemakers and as great merchants. When the Sanuma appeared, the Maiongong lands were nearly empty as a result of epidemic diseases and slavery... The rifles acquired from the Whites at the cost of much historical suffering, then served for the Maiongong to dissuade the Sanuma from making war and force them to live in peaceful existence... They acquired from the Maiongong the practice of planting and processing bitter manioc and of using canoes. Also they acquired dogs, pots, machetes, axes and beads long before they had continuous contact with the Whites" (Ramos, 1996:132-133).

Contact with the missions

The arrival of missionaries among the Ye’kuana in Auaris took place in the beginning of the 1960s. By that time, the Ye’kuana in Venezuela had already been through the experience of conversion and living together with Catholic and Protestant missionaries. At the beginning of the 1950s, the Protestant New Tribes Mission (NTM) began its work in the Federal State of Amazonas, in Venezuela. It supposedly obtained verbal permission from the government of Venezuela to develop its work, exploring the Orinoco and Manapiare rivers. Besides the NTM, Catholic missionaries also began their work in the states of southern Venezuela (Bolívar and the Federal Territory of Amazonas). The state gave its support to these missions, given that it considered the south of Venezuela to be an empty space which had to be occupied (Arvello-Jimenez 1991).

One of the consequences of the missionary work among the Ye’kuana in Venezuela, whether Salesian or Protestant, was the concentration of the population around the missions, which in some cases produced settlements with more than 400 people. Besides, obviously, the establishment of health services, schools, new professions, non-traditional agriculture, participation in the regional markets, among other things.

In Brazilian territory, the permanent arrival of the missionaries took place at the end of the 1950s beginning of the ‘60s, through the MEVA (Evangelical Mission of Amazônia) in the region of the upper Auaris River. As in other parts of the Brazilian Amazon, the Brazilian Air Force and the Brazilian Army served as intermediaries with the Indians in the clearing of a landing strip in Auaris and the entry of the missionaries.

According to the Ye’kuana, the interest of the missionaries was centered primarily on the Sanumá. So, the Ye´kuana decided not to live on the mission, but at a place relatively close by, approximately 15 minutes by canoe downriver or 20 minutes walk away. The Ye´kuana opted to not be transformed into «crentes»[believers], particularly because of the changes in behavior that conversion would imply: not drinking, not smoking tobacco, having only one spouse. They told the missionaries that their kin on the Venezuelan side had become crentes and had become weak as a result.

In 1980, a married couple of Canadian missionaries came to Auaris for their first experience among the Ye’kuana. But they only stayed two years, according to the Ye’kuana, due to conflicts with the «keepers of the tradition» – men who know the story of Watunna, the story of the first beings, of their deeds, their places, their songs, men who know the fate of the Ye’kuana –, who denied the version that «those who did not convert are descendants of Satan, they will burn with him, when the world ends, they will burn together». At that time, there were discussions among Ye´kuana leaders. The unconverted said that if the Watunna did not speak about the crentes, then they must be descendants of Fanhuro, that is, those who came to destroy the Ye’kuana. To celebrate their victory over the crentes, the Ye’kuana organized a festival that lasted three days, with much Yaddadi [fermented beverage] and tobacco. According to them, the Canadian couple supposedly witnessed the festival, did not like it, and decided to abandon the mission.

In the 1980s, the Army also set up a small base in Auaris, which was supposed to prepare the way for the establishment of a larger base, which would have an infra-structure to support, by the 1990s, the Fifth Special Border Platoon. A hydroelectric dam was built, the landing strip was widened and asphalted and installations to accommodate the military and their families were built.

Evangelization no, School yes

After the missionary couple who had the first experience of missionizing among the Ye’kuana community had left, the Indians claimed that they didn’t want religion, but they wanted a school, having been influenced by their kin who saw that there had been a proliferation of schools in indigenous communities in Venezuela.

In 1983, another missionary visited the community. She had experience with other indigenous populations and with teaching literacy. The missionary coordinator of MEVA at that time was supposed to have warned the chief Néri: «you don’t want our religion, the new missionary is a teacher, as you wished, but she is going to tell our stories in school, will you accept that?». Néri was supposed to have answered: «she can tell your stories, we will tell ours». So it was, the teacher came back the next year and worked with the Ye’kuana for 17 years.

With the arrival of the new missionary whose objective was to teach literacy to the adults and children, a process was set in motion which, in Venezuela, had already taken place: their settling in one place, the re-organization of tasks, which included time in school for the young people and children. Once again, they moved their houses, still close to the landing strip, but on the other side of the river. For them, crossing the river was not a problem, given that all the families had one or more canoes. With the founding of the school, finally they would have a person who would work exclusively with their community, besides being able to integrate that person into a project which was apparently much more Ye’kuana than of the Mission , that is, a school for the Ye’kuana.

Spatial mobility and socio-economic networks

The incursions by way of the rivers to the ranches along the Uraricoera River and Boa Vista meant that the Ye’kuana were much sought after as builders of canoes in the region. Besides this activity, work on the ranches involved making airstrips, bridges, clearing the areas of forest for planting, among other improvements. The trips they made to Boa Vista were for the purpose of buying clothes, salt, ammunition, pots, beads and other industrialized goods. In any case, the geographical position of the Ye’kuana limited the intense traffic between that community and other peoples or urban centers. The spatial distance seems to have served as a “filter" for this contact, which was both feared and desired.

It is worth noting that, through their mobility, they acquired industrialized goods directly, thus escaping from the norm which is demonstrated by so many other examples in Amazônia, in which such transactions are part of a system which produces dependence and exploitation by means of the so-called river merchants.

Contact with other ethnic groups in the east of the state of Roraima – including, besides canoes, exchanges with the Macuxi, Wapishana, Ingarikó, Taurepang and Wai-Wai - , they became known also for another Ye’kuana specialty, but this time, a female specialty: manioc scrapers – also through these exchanges, they became informed about numerous opportunities and experiences which were different from theirs, such as in religion, schools, indigenous political organizations, conflicts and, later, new opportunities for paid work. Although they maintained relations with other indigenous groups, especially relations of commerce, the Ye’kuana did not participate in political organizations or mobilizations in a systematic way, remaining distant from the process of political mobilization of those organizations.

If, by the 1970s, contact with the capitol was already made on a regular basis, it was only in the 1980s that several children of these Ye’kuana travelers came to the city, not only to work but also to study. These young people went on to live together with traditional families of the city. These networks were built as private relations and, for that reason, they weren’t extended to everyone. In this way, the children of those travelers went on to live with the families of the “network of contacts” of their parents in the capitol city.

These students were trained to work as laboratory microscopists, which was consistent with the opportunities that indigenous health assistance offered in the 1980s and ‘90s. Following the careers of these first Ye’kuana microscopists, we see that the search for professional training in the health area was the opportunity for which they had gone through public schools in the city of Boa Vista. The first microscopists went through the course for technical training with the Dutch organization “Medicine with no Frontiers", which works in the eastern region of the state of Roraima. After taking the test administered by the Ministry of Health, through the National Health Foundation, the two first Ye’kuana microscopists were hired by the French organization “Medicine of the World", and later by the Funasa, working in regions of the Yanomami Indigenous Land: Homoxi, Parafuri, Ericó, Auaris and Paapiu.

The gold rush

In the beginning of the 1980s, the village of Olomai was founded by the family of a Ye’kuana man married to a Sanuma woman. The married couple and their children moved downriver, and the Mission of Auaris accompanied the group, building a support base for the missionaries, which since then has become the new Mission post. Thus, houses and a new strip were built. This region eventually turned into a region that was disputed by the prospectors, and the Ye´kuana and Sanumá witnessed and lived up close to the drama of violence of prospecting on their lands (Ramos, 1990).

In the same period, other Ye’kuana extracted gold in another place, mainly in the region of Waikás, where several families moved to in the second half of the 1980s. They also witnessed the terror of the social relations marked by violence on the mining site. In many reports, they speak with perplexity of the carelessness with which bodies of the dead were thrown into the river. The violence in these relations made them seek work only amongst other Ye’kuana, whether privately or for outsiders, their allies.

Thus, facing their fear and seeking to find support in their “network of allies”, they could accumulate goods such as outboard motors, energy generators, machines for scraping manioc, clothes, radios, ammunition, weapons, sewing machines, among other things. They could even buy houses in the outskirts of the center of Boa Vista. Today, most of the men who were involved in some way with the prospecting site have other priorities: several are microscopists, others are teachers, others students, others are specialists in traditional songs, thus assuming ever more responsibilities with the community.

Village and society

The following description of the Ye´kuana village is taken from the text by the anthropologist Nelly Arvello-Jimenez (1983), who researched among the group in Venezuela:

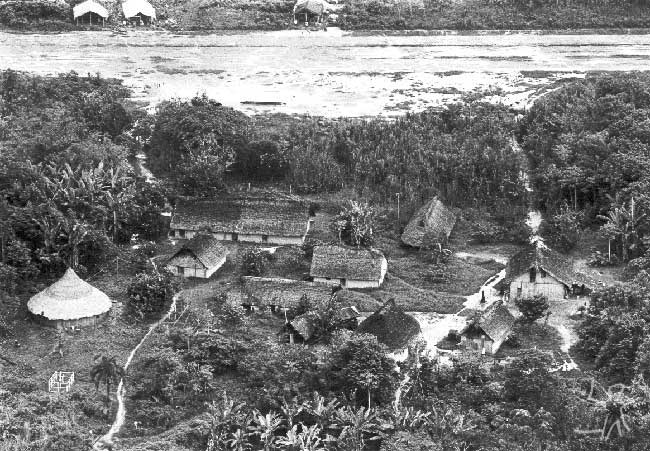

A clearing in the middle of the forest indicates the presence of a village. This area is made up by zones arranged in concentric circles, with the communal house – or maloca - at the center, which has a rounded base and cone-shaped roof. It has the capacity to provide shelter for about 60 people, and it is also divided into internal circular sections: a) annaca: where the communal meals are made, visits are received and festivals held; at night, it becomes a sleeping-room for the single young men; b) äsa: a space around the annaca divided into compartments the dividing walls of which do not reach the ceiling; each compartment shelters an extended family.

Surrounding the house there is a space called jöroro, used as a meeting place for the women and which can also be used for festivals, as an alternative to the annaca. Following the spatial organization of the village, there are the work houses, there being one per extended family. These are small houses, rectangular, with no walls, and with a roof of two slopes. There the women scrape manioc, cook, sew and make scrapers, and the men work on artwork, fix their hunting and fishing tools, etc.

Finally, surrounding the work houses there are small gardens – one for each extended family – where they cultivate tobacco, cotton, sugarcane and medicinal plants. These gardens mark the end of the clearing. At distances which can be crossed on foot, one can see other clearings that correspond to gardens.

Different from this traditional pattern described by Arvello-Jimenez, the community of Auaris no longer has this communal house, although a house for meetings and festivals was built in the center of the village.

Marriage and descent

The Ye´kuana, like many indigenous groups of the Amazonian region, believe that every sexual relation contributes to the formation of a child, which is the result of a series of sexual acts. Semen accumulates gradually in the uterus of the woman, and all men who contributed to this process are considered fathers of the children.

Both the mother and the fathers observe a series of pre- and post-natal restrictions. Before birth, most of the restrictions have to be observed by the future mother, while after birth, most taboos apply to the fathers.

The Ye´kuana practice polygyny – that is, a man can have more than one wife –, preference being given to sororal polygyny – in which a man is married to several sisters. The existence of available women in the village poses limits to polygyny, such that the only men who are invariably polygynous are the shamans.

Preferential marriage among the Ye´kuana occurs between cross-cousins (in which Ego marries the mother’s brother’s daughter or father’s sister’s son). Marriages are prohibited between classificatory siblings (children of the same parents or parallel cousins) and next-generation kin. After marriage, the man goes to live in the house of his wife (or in the compartment of the house) and must be subservient to his wife’s father.

The villages are divided into two types of residential units: one which consists of those who share a single compartment in the house and can be considered an “incipient extended family” – generally comprised of father, mother, single sons, single daughters, married daughters and grandchildren – and one which is produced by a set of these compartments, that is, in which all the inhabitants of the roundhouse who can be considered a “mature extended family”.

Political organization

The village consists of a politically autonomous community. The chief of the village is the coordinator of collective activities and representative of the group to the world outside. But he does not have powers to give arbitrary orders, so his actions have to be exemplary and reflect the decisions made collectively in the circle of the elders. His position is different above all because he combines knowledge, technical efficiency, ritual wealth and the organizational capacity to orchestrate social relations.

Within Ye´kuana communities there is a hierarchical organization which is still highly respected, where the elders and especially the chiefs are always consulted in matters of collective decisions. Thus, the circle of the elders has to answer to a consultative counsel the members of which generally are heads of the “extended families” which occupy the apartments of the roundhouse, the chief of the village and families connected to the village, as well as heads of nuclear families or independent composite families.

Subordinate to the circle of the elders, there is the circle of the young men, comprised of married and single young men. Both groups get together at least once a day during the communal meal. The young men and the elders eat in the annaca in separate circles, but there is no strict separation in the composition of these circles during the meals. After eating, they discuss whatever question that may be of interest. Conversations to plan collective work parties are frequent after the morning or evening meals, while the conversations between the chief and his aide generally occur at dawn or before the evening meal.

There are even leaders of commercial trips and hunting expeditions, duties which are not fixed. Finally, ritual specialists have notable political influence and social position : shamans (jöwai) and singers (aremi or a´churi edamo). In any case, those who have the most collective knowledge are the elders and shamans, those who really know by memory the names of people and their journeys on this earth and in other cosmic spaces.

Relations among neighbors

The relation among the Ye’kuana and Sanumá (Yanomami) has been marked by wars, but it was followed by a period of coming together which lasts up to the present day (Ramos 1980; 1990). A period of coming together which has involved exchanges of knowledge and techniques, that have to do above all with food and probably also with medicinal plants, food production, and including peaceful co-existence and even marriage between the two groups.

In Brazil, although there are marriages with Sanumá women, the group continues to follow the ways of their distinct social organization, in which the Ye’kuana men who marry with Sanumá women leave their communities to live in the communities of their wives. The fact that today the Sanumá are a majority around Auaris has not changed the marks of differences. Each group upholds its own festivals, rituals, schools, teachers,, microscopists, and beliefs. Even in the field of traditional knowledge, there are many exchanges which take place, and the specializations of each group are respected, as for example that the Sanumá are better in traditional hunting. The traditional techniques of the Ye’kuana for building houses are also respected by the Sanumá.

There is a certain rivalry and reciprocal admiration between the two groups which occurs in the following way: due to their social organization , the Ye’kuana have succeeded in undertaking community projects and producing large gardens, building large houses, and a support house in Boa Vista, they have been able to gain access to salaried work sooner, or in other words, they “know how to deal with the world of the whites”; while the Sanumá supposedly spend more time in hunting, and on trips, or in other words: “the Whites take care of them”. In short, it is a world full of contradictions, that recalls the past of wars that took place between the two groups in this territory.

Cosmology

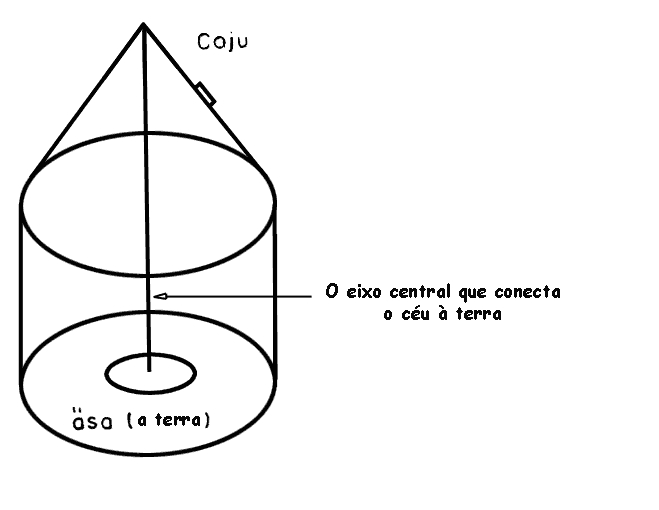

The Ye´kuana conceive of the universe as being comprised of two parallel planes : caju (the sky) and nono (the earth). In nono, the lower plane of the universe, the supernatural was long ago neutral (or at least its manifestations were unknown to the inhabitants of the earth). Then the Sun father let three magical eggs fall down. The first two opened and from them came Wanadi, a mythical culture hero, and his brother. The third did not break open, but was smashed and deformed. Wanadi then threw it into the forest. With this second fall, the egg opened and Cajushawa, full of resentment and hatred, appeared on earth and turned into the negative manifestation of the supernatural. Since then the people of Cajushawa (the demons or odosha) have proliferated over the earth, dominating the invisible reign of the earth. In contrast, Wanadi, the benevolent expression of the supernatural, after having lived on the earth for a time during which he struggled against Cajushawa, left the earth in the hands of people, the Ye´kuana, and it is up to them to fight against the demons.

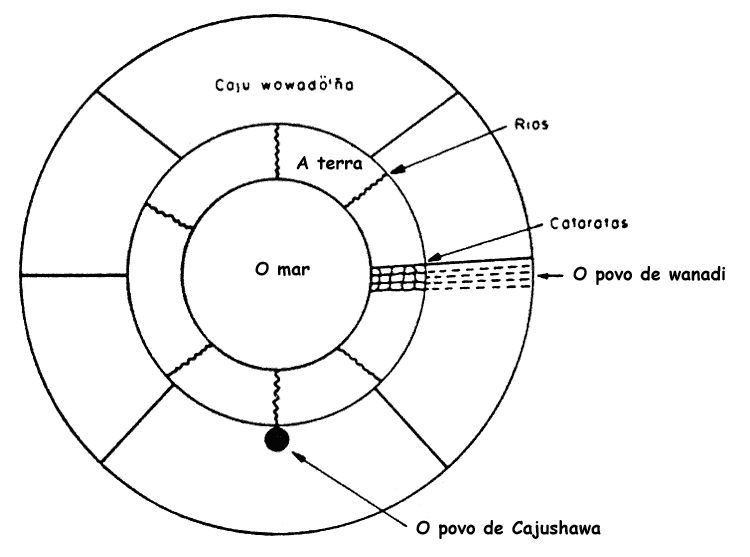

The makeup of the earth has at its center an internal circle of water called dama (the sea), which is surrounded by another circle, nono (the earth properly speaking), which has arteries of water, tuna (the rivers which come from the sea). Surrounding the earth there is another circle from which reclined bolts emerge which are the pillars that hold up the sky. This space is called caju wowaö´ña, or literally « the paws of the sky ». Besides holding up the sky, caju wowadö´ña is the limit of the reign of Cajushawa. The villages to the east it is said belong to caju wowadö dawono (the lower part of caju wowadö). To the east there are innumerable waterfalls very difficult to reach that begin on the earth, run underland in caju wowadö´ña and reappear in the sky in the form of calm water. When Cajushawa pursued Wanadi, he was not able to cross over these waterfalls and had to stay on earth.

Caju (the sky), the upper plane of the universe, is divided into eight layers, which are the reigns of the jöwai. The villages of Wanadi and the Sun are located in an inaccessible place of caju, concentrated in a single place beyond the world in which the visible beings (the Ye´kuana) and the invisible beings (the demons of Cajushawa) unceasingly compete, and the balance between the positive and negative forces is very unstable. Living in this place, Wanadi is completely distant from the problems of the earth.

The geography of the universe and the geography of the roundhouse are marked by a great similarity. But, more than that, the roundhouse can be understood as a replica of the cosmos: its parts correspond to each of the significant divisions of the sky and earth. The annaca (or internal circle) corresponds to dama (the sea in the center of the world). The next circle which makes up the earth (nono) corresponds, in the roundhouse to the äsa (the compartments/ sleeping quarters). On the edges of this second circle are the pillars which hold up the roof. The larger beams are called sirichäne, which literally means « support for the stars ». In the Ye’kuana concept of the universe this space corresponds to caju wowadö´nã, or « the paws of the sky ». The cone-shaped ceiling of the roundhouse, in turn, is shaped like the representation of the upper plane of the universe, with the tip being the dwelling-place of Wanadi and his father. In the roundhouse, there is a window in the ceiling that opens to the east, in the direction of Wanadi.

Besides the demons, odosha, there is another form through which the supernatural manifests itself in a negative way. According to the Ye´kuana, the life systems (animal and plant, for example) have invisible equivalents or « owners » in the invisible world. When the Ye´kuana affect the visible manifestations of these beings – in hunting an animal or cutting down a tree, for example – they bring about an imbalance in the invisible world. The invisible forces then react, causing misfortune, sickness or death to the aggressors. To deal with this problem, the Ye’kuana perform rituals prior to using certain products of nature, like forest fruits, game animals, resins (for example, the caraña which is used in body painting) etc. These products are « blown over »[that is, with tobacco smoke and orations] in order to drive away the supernatural force that is found stuck in them.

Shamanism and rituals

Any Ye'kuana can acquire a certain ritual skill to control evil power, even if it is specific. But the ritual system is dominated by specialists who have command over special powers : the jöwai (also known as cadeju), whose principal function is to cure sicknesses. They possess a power which is similar to Wanadi and his brothers, who were the first shamans of the earth. This power is not the same among all shamans, but is stronger in some.

Another group of specialists is the "owners" (edamo) of sacred songs (generally known as a´churi or aremi) and are called a'churi edamo or aremi edamo. Both types of specialists are able to perform rituals for good or evil purposes, since Wanadi and Cajushawa come from the same source.

The rituals celebrated by an a'churi or aremi edamo generally consist of : a) an exorcism, a magical invocation or sacred chants (aremi or a'churi) which vary in size and content; b) appropriate gestures – with the hands or breath – to expel and drive out the malignant forces or demons (odosha) ; c) use of magical amulets (eritrotojo).

The rituals can be classified as “communal", "private" and "individual". The entire community participates in the first type which is led by the a´churi or aremi edamo. They occur rarely and consist of ceremonies connected to events such as the clearing of a garden or the inauguration of a house.

The private rituals are more numerous and the number of participants varies. They include, for example, the celebration of a birth, first menstruation or the first harvest.

Individual rites are even more numerous, and their sole participant is the a'churi or aremi edamo. Examples of these rites are the exorcism that accompanies the blowing over any kind of meat that will be eaten by an individual for the first time; or before consuming forest fruits ; or to neutralize the evil forces that come with great rains or floods; to find a lost person or animal; for the making of canoes, woven cloth or other objects. There are also individual rites that act as preventive or curative magical medicine, or even « black magic » (lethal blowing on the victim).

The "Ye'kuana promise"

Ye'kuana cosmology has a prophetic dimension that is protagonized by the shamans. Besides knowing the past, the shamans can see the future, the “Ye’kuana promise”. And fate is dramatic: “first the shamans will disappear, then the wise men, then the singers, when the last Ye’kuana dies the earth will burn, the Whites will suffer greatly because they will be many, there will be no more water, the rains will cease to fall.” The Ye’kuana will meet Wanadi; but there is no “salvation” for all in the Ye’kuana “promise”. Thus, shamanism is the main reference point for collective destiny, or in other words, the vision of the Ye’kuana fate is related to shamanic practices.

For the elders, the present changes are the result of the changes in the times; according to them, the lack of observance of the taboos, as well as certain food restrictions and use of body painting, work together to produce an increase in sicknesses and weakening of the young people. Even with an apparent dose of pessimism, the present-day problems confirm and give value to the “traditions”, especially for the shamans who foresaw such changes.

Presently, the Ye’kuana do not have shamans in their communities in Brazil, but there are specialist midwives, traditional singers and specialists in magical and medicinal plants. Contact with their shamans in Venezuela takes place both by way of visits and by radiophone. Although they receive permanent health assistance in their communities, various problems still are treated in a traditional way, with songs, blowing, and use of plants, all of which go along with a food diet.

The Time of the festival and the Time for the School

Presently, the main festivals, or those of greater duration, take place in the period of the school holidays, except for Carnaval, which they have already incorporated into their calendar. But other activities, especially the building of houses, can be done independently of the school calendar. Also, several rituals, like the inauguration fo a house or the end of a period of restriction after first menstruation, require the consumption of Yaddadi [fermented beverage] and they don’t always take place outside the school calendar, which causes a certain tension.

In relation to the rite of passage of the girl to adulthood, for example, after the girl’s first menstruation, traditionally the girl stays for a year secluded most of the time weaving cotton in a compartment of her house which is set aside for that purpose. She cooks her own food and goes fishing alone. During this period she doesn’t use ornaments, she cuts her hair very short and reduces to a minimum her body decoration and social contact. The end of her seclusion is marked by a ceremony during which those who went through seclusion paint themselves and put on their beads. All of this goes along with songs and, at the end, the young women drink a lot of traditional drink, and are later taken to their hammocks. From that time on, they can marry, paint themselves and go to parties, among other things.

The period of seclusion overlaps with the school calendar, but in any case, the school has adapted as it can to the Ye’kuana calendar, letting the student who is in seclusion go to classes whenever possible. Besides that, currently the school year begins and ends before the urban calendar, which means that the end of the school year takes place in the middle of November, coinciding with the dry season, which is also the time for clearing the gardens and for building, that is, collective activities. There is greater movement among the families in this period, when they cut their gardens, various families visit their kin in other communities or they simply go off into the forest to hunt.

Renewing the Tanöökö

The main festival of the Ye'kuana is the Tanöökö, but it hasn’t been celebrated in more than 15 years in Brazil. Generally it took place when the men who had gone to Boa Vista over the rivers with their canoes, returned. These days, only the men from Waikás still make the trips by canoes to the ranches near Boa Vista. In Auaris, from the 1990s on, river transport has intensified.

Two of the men who conducted the Tanöökö festival unexpectedly died in the beginning of the ‘90s, one of them because of measles and the other because of a snakebite. No doubt this loss was important for explaining why the festival was no longer held. In any case, the teachers and traditional Ye’kuana leaders intend to show the younger people how the Tanöökö festival was done.

According to the elders, the festival involved the whole community which had to make musical instruments; there are wrestling matches in which one needs to know the rules; part of the community goes off to hunt; and another part prepares the food that will be consumed during the festival along with the game animals.

Productive activities

Despite their insertion over the last few decades into urban centers like Boa Vista and all the modernity which has come to the villages – which includes electrical energy since the year 2000, TV, schools, industrialized medicine, among other things -, the Ye´kuana maintain their food traditions and their ways of producing this food. They are agriculturalists, gatherers and they hunt and fish, they still keep small domestic animals, especially dogs and birds. Their basic diet is fish soup, pepper and manioc bread.

In the Yanomami Indigenous Land, they, like their neighbors, the Sanuma, face game and fish scarcity. By contrast, they have large and bountiful gardens. Together with this production, clearly, there is a whole series of work activities, rituals that still organize time and space in Ye'kuana villages. Salaried professionals actively participate in this social and economic life, not only by contributing financially to their fathers-in-law and to the community, but also directly in community work activities, like the construction of houses or the clearing of new gardens.

They are excellent canoe-makers and navigators. In women’s work, manioc scrapers are highly valued. These products – canoes and manioc-scrapers – are the two main Ye'kuana specialties which are traded with other Carib groups and the Wapichana in Roraima, and there is a high demand for their manioc scrapers in the region. Similarly, there is a great demand from the NGOs and the Funai for Ye’kuana canoes in the health posts, schools and Funai posts in the indigenous area.

Note on the sources

There are many publications on the Ye'kuana in Venezuela. Besides the expeditions by Schomburgk, Koch-Grünberg, Gheerbrant, we have the ethnography by Nelly Arvello-Jimenez (1974) and the works by De Civrieux (1970), De Barandiaran, Daniel and Fuchs, Helmuth who wrote various works in the 1960s; Coppens and Walter in the ‘70s and ‘80s; Guss and David had important works published in the ‘70s, ‘80s and ‘90s. Recently Philippe Descola (EHESS-Paris) has been advising two doctoral theses on the Ye'kuana, one by the author of this entry, on the Ye’kuana in Brazil, and one by Naluá Monterei Rodrigues, in Venezuela. At the moment, the main reference on the group in Brazil is the work of Alcida Ramos.

Sources of information

- ALBERT, Bruce. Developpement et securité nationale : les Yanomami face au projet Calha Norte. Ethnies, Paris : Survival International, n.11/12, p.116-27, 1990.

- --------. L'Or cannibale et la chute du ciel : une critique chamanique de l'économie politique de la nature. L'Homme, Paris : École des Hautes Etudes en Sciences Soc., v. 33, n. 126/128, p. 349-78, abr./dez. 1993. Publicado também na Série Antropologia da UnB n. 174, 1995.

- ARVELO-JIMENEZ, Nelly. Indigenismo y el debate sobre desarrollo Amazónico : reflexiones a partir de la experiencia Venezuelana. Brasília : UnB, 1991. 40 p. (Série Antropologia, 106).

- --------. Political relations in a tribal society : a study of the Yekuana of Venezuela. New York : Cornell University, 1971. (Cornell University Dissertation Series, 51).

- --------. Relaciones politicas en una sociedad tribal : estudio de los Ye'cuana, indígenas del Amazonas Venezolano. Quito : Abya-Yala ; Roma : MLAL, 1992. (Colección 500 Años, 51.

- --------; CONN, Keith. The Ye'kuana self-demarcation process. Cultural Survival Quarterly, Cambridge : Cultural Survival, v. 18, n. 4, p. 40-2, 1995.

- CHIAPPINO, Jean; ALES, Catherine (Eds.). Del microscopio a la maraca. Caracas : Ex Libris, 1997. 402 p.

- DE CIVRIEUX, M. Mitologia Makiritare. Caracas : Monte Avila Editores, 1970.

- GEFFRAY, C. Chroniques de la servitude en Amazonie brésilienne. Paris : Khartala, 1995.

- GODELIER, M. Anthropologie sociale et histoire local. Gradhiva, s.l. : s.ed., n.20, p.83-94, 1996.

- GONGORA, Majoi Favero. Ääma ashichaato: replicações, transformações, pessoas e cantos entre os Ye'kwana do rio Auaris. São Paulo : USP, 2017. [Tese de doutorado]. Disponível em: < https://www.academia.edu/31493133/%C3%84%C3%A4ma_ashichaato_replica%C3%A7%C3%B5es_transforma%C3%A7%C3%B5es_pessoas_e_cantos_entre_os_Yekwana_do_rio_Auaris >

- GUSS, David M. Tejer y cantar. Caracas : Monte Avila Eds., 1990.

- --------. To weave and sing : art, symbol, and narrative in the South American Rain Forest. Berkeley : Univ. of California Press, 1989. 288 p.

- JIMENEZ, Simeon; PEROZO, Abel (Eds.). Esperando a Kuyujani : tierras, leyes y autodemarcacion - Encuentro de comunidades Ye'Kuanas del Alto Orinoco. Caracas : Gaia, 1994. 96 p. (Bibl. de Antropol.: La cotidianidad Pluric. de Venezuela, 1)

- PY-DANIEL, Víctor. Oncocercose, uma endemia focal no hemisfério norte da Amazônia. In: BARBOSA, Reinaldo Imbrozio; FERREIRA, Efrem Jorge Gondim; CASTELLON, Eloy Guillermo (Eds.). Homem, ambiente e ecologia no estado de Roraima. Manaus : Inpa, 1997. p. 111-56.

- RAMOS, Alcida Rita. Auaris revisitado. Brasília : UnB, 1991. 72 p. (Série Antropologia, 117)

- --------. Memórias Sanumá : espaço e tempo em uma sociedade Yanomami. São Paulo : Marco Zero ; Brasília : UnB, 1990. 344 p.

- --------. A profecia de um boato. Brasília : UnB, 1995. 22 p. (Série Antropologia, 188)

- --------. Sanumá, Maiongong. In: --------. Hierarquia e simbiose : relações intertribais no Brasil. São Paulo : Hucitec, 1980. p.19-130.

- RODRIGUEZ, Alberto Jimenes; SARMIENTO, Alberto. Usos de la fauna por comunidades Ye’kwana de la cuenca de rio Caura, Guayana Venezuelana. Georgetown : Iokrama International Centre for Rain Forest Conservation and Development, 2000. Texto apresentado no Woorkshop “Critical Issues in the Conservation and Sustainable and Equitable uso of Wildlife in the Guiana Shield.

- SEGALL, Thea et al. Los Ye'kuana : un reportaje fotografico..Caracas : Ministerio de Educacion, 1979. Boletín Indigenista Venezolano, Caracas : Ministerio de Educación, v.18, n.15, p.53-98, jan./jun. 1979.

- SOUZA FILHO, Julieta. A música dos índios Yekuana : flautas e tambores davam boas-vindas a um visitante. Ciência Hoje, Rio de Janeiro : SBPC, v. 18, n. 106, p. 77-9, jan./fev. 1995.