Wapishana

- Self-denomination

- Where they are How many

- RR 11309 (Siasi/Sesai, 2020)

- Guiana 6000 (Forte, 1990)

- Venezuela 37 (XIV Censo Nacional de Poblacion y Viviendas, 2011)

- Linguistic family

- Aruak

As well as the valley of the Uraricoera river, the Wapishana have traditionally occupied the valley of the Tacutu along with the Macuxi, who also inhabited the upland region further to the east of Roraima. Currently the Wapishana population totals around 13,000 people, living in the interfluvial region between the Branco and Rupununi rivers on the frontier between Brazil and Guyana. They comprise the largest population of Arawak speakers in northern Amazonia.

Direct contact

Visite the '''Conselho Indigena de Roraima - CIR (Indigenous Council of Roraima)''' website

Names

The area today forming the Wapishana territory – distributed between the Branco river valley in Brazil and the Rupununi valley in Guyana) – was primarily occupied until the 1930s and 40s by a number of groups, including the Vapidiana-Verdadeiro, Karapivi, Paravilhana, Tipikeari, Atoradi (also written Aturaiú or Atorai), Amariba, Mapidian (Mapidiana, Maopityan) and Taruma (Farabee 1918; Herrmann 1946).

According to Herrmann (1946), based on the accounts of the Benedictine missionary M. Wirth, the Vapidiana-Verdadeiro inhabited the area around the Urocaima ridge, between the Parimé and Surumu rivers; the Karapivi lived on the Surumu, Cotingo and Xumina rivers; the Paravilhana, on the Amajari river; the Tipikeari, between the Uraricoera, Mocajaí and Cauamé rivers; and the Atoradi, the Lua ridge. The Amariba, Mapidiana and Taruma, all ethnonyms recorded by Farabee, were mainly located in the Rupununi river valley.

In the colonial reports, these ethnonyms are given to distinct peoples or ‘nations.’ Farabee claims that historically the Wapishana expanded eastwards and in the process incorporated these linguistically and culturally proximate groups who were verging on extinction due to the epidemics spread by contact with the whites.

This hypothesis is supported by later authors such as Butt-Colson (1962) and Migliazza (1980). However, there is no documental corroboration of a Wapishana expansion eastwards, centred on the valley of the Uraricoera river, nor even of an outbreak of epidemics decimating these populations between the end of the 19th century and the first decades of the 20th century, as Farabee suggests.

A more plausible hypothesis is put forward by Janette Forte and Laureen Pierre (1990), who argue that at the same time as these ethnonyms – which identified various dialect subgroups – fell into disuse, the ethnonym Wapishana expanded to include all the subgroups. Indeed, even today slight variations in dialect are observable. This proposition is more in line with the image projected by the Wapishana themselves, who today identify dialectical variation as the only distinguishing feature between the inhabitants of the Uraricoera river valley and those of the Tacutu/Rupununi.

Language

The Wapishana language is classified as a member of the Arawak linguistic family (Rodrigues 1986). The term Arawak is more generally used to refer to the Arawakan or Lokono languages spoken in Venezuela, Guyana, Suriname, French Guiana and in some of the Antilles islands. Another term used to designate the Arawak family is Maipuran.

The desire to retain the maternal language is especially significant for the Wapishana living on the outskirts of urban centres on the Brazilian side. As Franchetto’s sociolinguistic survey (1988) emphasizes, use of the native language by the Wapishana is defined by two distinct realities.

Those inhabiting areas close to the urban centres live in a bilingual environment composed of Portuguese and Wapishana with a growing dominance of Portuguese, especially among the younger generations. In contrast, those living in malocas further away from the cities and who maintain constant contact with kin in Guyana remain almost completely monolinguistic in the Wapishana language.

According to Migliazza (1980), more than 80% of the Wapishana can speak the national language with which they are in contact, Portuguese in Brazil or English in Guyana, and 30% of them can also speak Makuxi or Taurepang, both members of the Carib language family.

In fact, because of the ease with which one can cross the border between the two countries, it is common to find people who speak Portuguese and English, as well as the maternal language. On the other hand, there are older people living in remote malocas who speak only their own language. During Migliazza’s period of research (1985), the number of Wapishana speakers was around 60% of the population. More recent data from the Insikiran Indigenous Training Centre (2003) indicates that this percentage had fallen to just 40%.

Location

The grassland (or farming) region includes the area from the Branco river to the Rupununi river, a watershed region between the Amazon and Essequibo river basins. A similar configuration, surrounded by forest and mountains, forms part of the crystalline rock formations of the Guiana shield, which border the lower Amazonian plateau at altitudes ranging from 700 to 3300 metres above sea level. To the north and west, the grasslands are ended abruptly by the Pacaraima mountain range; to the east and south, there is a more gradual transition to the Amazonian forest as the vegetation becomes denser and the mountains lower.

In Brazilian territory, in the northeastern portion of Roraima, the Wapishana villages are predominantly located in the Serra da Lua (Moon Ridge) region between the Branco river and one of its affluents, the Tacutu. On the lower Uraricoera river, another affluent of the Branco, most of the villages contain a mixed population of Wapishana and Makuxi. Mixed villages – Wapishana and Makuxi or Wapishana and Taurepang – are also found on the Surumu and Amajari rivers.

The continuous tract of Wapishana territory in Brazil was violently sliced up during official demarcation of their lands at the end of the 1980s. This produced various small indigenous areas in which the Wapishana were confined to lands usually surrounded by cattle ranches. Currently there are 21 such small Indigenous Territories, 15 of which are shared with the Makuxi. In addition, part of the population inhabits the São Marcos IT together with the Taurepang and Makuxi, and the Raposa Serra do Sol along with the Pemon (Makuxi and Taurepang) and the Kapon (Ingarikó and Patamona).

To learn more about the long process of demarcating the Raposa Serra do Sol Indigenous Territory, see ISA’s special report.

In Guyana, the Wapishana villages are located between the Tacutu, Rupununi, and Kwitaro rivers, bordering the Makuxi territory in the Kanuku mountains to the north, and extending as far as the Wai-Wai territory to the south.

Population

In 1997 the Wapishana population was estimated to be between 10,000 and 11,000 people. In Brazil, around 3,000 to 4,000 are estimated to live in villages with a further thousand people in towns and farms. According to Funasa’s data for 2008, the Wapishana population totals around 7,000 individuals. For Guyana, the most recent estimate is about 6,000 people (Forte 1990).

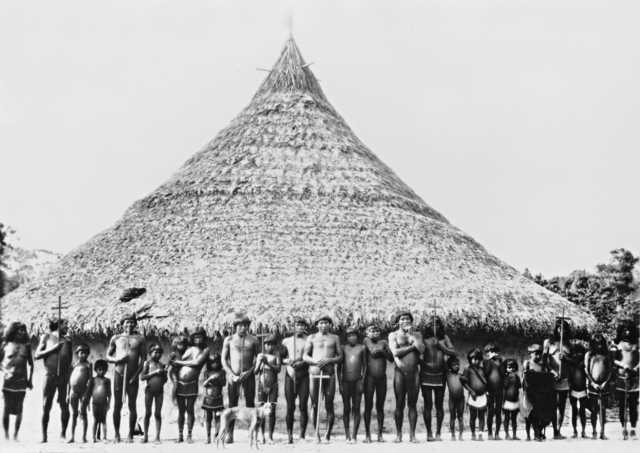

Diverging from the general ethnographic model for the Guianas (Rivière 1984), the Wapishana village pattern typically presents considerable stability – villages such as Malacacheta and Canauanim were mentioned by the traveller Henri Coudreau, who visited them in the 1880s, occupying their current locations. They also exhibit a high demographic density: the Wapishana villages in Brazil contain an average population of 150 inhabitants, while the figures are even higher for the villages in Guyana, which average around 500 inhabitants (Forte 1990).

History of contact

Inhabitants of a frontier region formed by colonial partition, the indigenous peoples of the grasslands and uplands of the middle and upper Branco river – including among them, the Wapishana – experienced a double process of colonization from the mid 18th century onwards. Arriving from the Amazonian valley, the Portuguese initially attacked the indigenous population occupying the Branco river in slave raiding expeditions. Later, towards the end of the century, village settlements were established there.

The Dutch, for their part, reached the region via an extensive network involving the exchange of manufactured goods for Indian slaves. After the transfer of Guyana to the British in the aftermath of the Napoleonic wars, the interior of the colony remained untouched for a long time: colonial administration was only implemented at the end of the 19th century, while occupation was only consolidated in the 20th century.

During the 19th century, the British colony, centred on the production of sugar along the coastal region, invested heavily in the importation of indigenous labour to replace African slave labour. Thus farming in the grasslands of the Rupununi river, based on indigenous manual labour, began at a small scale in the 1890s, reaching commercial levels only in the 1930s.

The same applied to the Branco river valley where, despite the initial phase of enslavement and village settlement in the 18th century, contact intensified with land occupation for farming, beginning with the arrival of non-military colonists in the second half of the 19th century. It was this civil colonization, which established the region’s agriculture-based economy, that inaugurated the plundering of indigenous territories.

The occupation of the region’s lands was accompanied by measures for incorporating the indigenous population into the lowest classes of the regional non-indigenous society forming at the time.

According to the chronicler Lobo D’Almada (1861 [1787]), the Paravilhano, Aturahi and Amaribá were located between the headwaters of the Tacutu river and the Rupununi. The Wapishana, for their part, occupied the green highlands of the Mau river as far as the upland areas on the Parimé.

The report by the traveller R. H. Schomburgk (1903 [1836-9]), who explored the region between the 1830s and 40s, provides important clues concerning the trajectories followed by the peoples living on the Branco river in the early 19th century. His report tells us that during these first decades the peoples inhabiting the western area of the river were relocating to areas even further west, heading towards the Orinoco river basin, with various ethnic groups becoming absorbed by others, which perhaps explains the disappearance of some ethnonyms in later sources.

To the east of the valley, Schomburgk also observed a process of territorial relocation: the Wapishana and other peoples inhabiting the area between the Lua and Carumá ridges, such as the Atorai and Amariba, had migrated to the far east.

He also claimed, wrongly as it happens, that the Paraviana had migrated towards the Amazon. This mention of a supposed migration of the Paraviana is important, though, since it verifies their disappearance around this period of the 19th century, despite being cited as one of the most populous groups on the Branco river in the 18th century (Ribeiro de Sampaio 1872 [1777]).

We can surmise that, brutally affected by the slavery and village resettlements undertaken by the Portuguese in the 18th century, the remaining Paraviana were absorbed into the Wapishana fairly early on. This process seems to have occurred gradually throughout the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century among the peoples who Schomburgk then considered to be ‘related’ to the Wapishana – namely the Atorai and Amariba – as well as the Tapicari and Parauana, since in the 1930s the linguist and Benedictine missionary M. Wirth would classify all these peoples as dialectic groups of the Wapishana.

The sequence of epidemics affecting the region since the colonial period undoubtedly contributed to its depopulation. For example, a smallpox epidemic, begun in the Negro river area in the 1880s, was probably spread to the Branco river by Indians fleeing from the large numbers of people in quarantine. Another epidemic, this time a large flu outbreak, raged through Guyana at the end of the 1920s, affecting the Atorai and Wapishana populations in particular.

The forced recruitment of indigenous workers on the Branco river continued unabated throughout the 19th century, focused during the first decades on the groups living along the Negro river. This demand increased exponentially with the exploration of caucho rubber and balata gum on the lower Branco river from the 1850s onwards.

At the end of the 1880s, the French traveller Henri Coudreau (1887) provided a vivid description of a regional economy that depended entirely on the indigenous workforce. Use of native labour persisted within the farming economy installed in the area in the final decades of the century.

Between the end of the 19th century and the start of the 20th, non-military colonization of the grasslands of the Branco and Rupununi rivers (the latter by now under British control) led to the occupation of the Wapishana territory, along with their systematic recruitment as a workforce on the Brazilian and British farms. Devastating in its effects, the land occupation hemmed in villages and provoked the mass exodus of the population, especially from the Brazilian area to the British colony. A reverse flow took place more recently in the 1970s.

The occupation of Wapishana territory during the first decade of the 20th century also coincided with the start of the work of the Indian Protection Service (SPI) and, much more intensively, of Benedictine missionaries. Even though the Wapishana villages were located far from the Benedictine missionary centre on the Surumu river, they were subject to continual mission visits, as well as school education run by Benedictine nuns in the villages closest to the urban centre of Boa Vista and, finally, the systematic recruitment of children for education in the boarding school run by missionaries on the Surumu river. A similar system was implemented in neighbouring Guyana where the conversion of the Wapishana was begun by Jesuit priests during the same period.

Recent situation

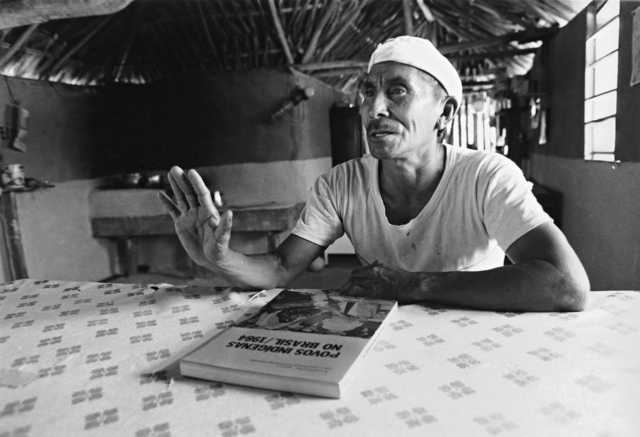

The Wapishana villages are still affected by labour recruitment both for domestic work and for work on the farms that cut across their territory. From the 1970s to the start of the 1990s, labour exploitation was mainly faced by the Wapishana populations living in Guyana who, politically persecuted by the Forbes Burnham regime, were forced to accept lower wages and poorer working conditions than those found in Brazil.

The villages are still subject to intense harassment by political parties during election campaigns. Targeted by the same corrupt practices found elsewhere in Brazil in relation to low-income populations, votes are either bought by individual candidates in the region on a one-to-one basis through the distribution of much-desired tins of oil or sardines, or through presents to the village as a whole when the party controls the government machine. Since the 1994 election campaign, almost all the Wapishana villages, from Uraricoera to Tacutu, started to boast not only tractors, but also satellite TV dishes opportunely donated by the Roraima state government.

In addition, there is the school system. Indigenous schooling was begun in Roraima by Catholic missionaries in the first decade of the 20th century. However, this religious schooling had little impact on the Wapishana villages since among few of today’s older adults were taught during this period. Systematic schooling effectively took hold from the military dictatorship inwards when schools were implanted in the villages. At the end of the 1990s, all the villages had primary schools; secondary education was provided at the Malacacheta village and in the city of Boa Vista.

The village and its relations

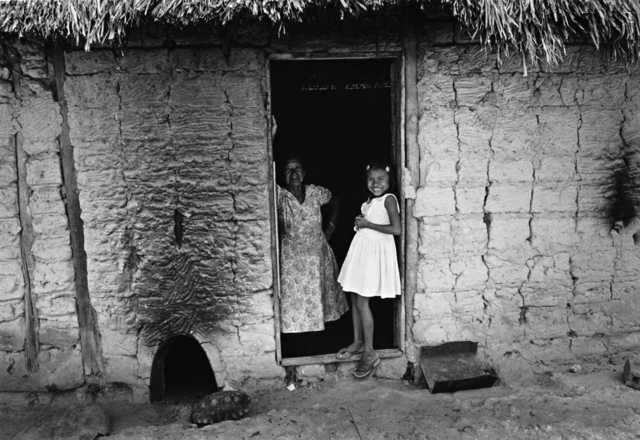

Scattered across the grassland, the Wapishana houses at first sight appear randomly distributed. They are in fact linked to one another by narrow trails, imperceptible to the untrained eye, secondary to the broad path leading to the patio of the religious centre and the school and from there heading out of the area. Seen from closer up, these faint trails, almost lost among the remoter houses, become denser between the closer houses and indicate the local sociological groupings, namely the kingroups.

Whenever possible, married daughters prefer to build their house close to the maternal house. They raise their children alongside their own mother, sharing the domestic work and food. The paths linking their houses therefore reflect everyday exchanges: the meat that, hunted by her husband, the daughter conscientiously offers to her mother and sisters; help during labour and sicknesses; the path to the swiddens taken by all the women together in the morning; afternoons spent spinning cotton or grating manioc while the children play in the grandmother's yard. Although the distribution of caxiri, a drink made from manioc, involves a larger number of kingroups, it does necessarily involve the entire village; ‘sweet’ caxiri – weakly fermented with a low alcohol content and intended for quotidian consumption – is produced and shared within this intimate circuit formed by a mother and her daughters.

Productive activities

The Wapishana obtain the resources needed for survival mostly from agriculture, which is conducted using the traditional slash-and-burn technique. Normally the families possess their own swiddens, though they may also work collectively in the swiddens of other families.

The process is as follows: the family owning the swidden requests help from other members of the maloca when needed, for example when clearing the land and harvesting. During this period of collective work, the family receiving the help offers everyone food and their typical drink, caxiri. This process is repeated for all the families who require assistance from the collective group.

Crops include beans, maize and especially manioc. Beans and maize are used in similar ways to non-Indians; beans are part of the daily meal, while maize is consumed in both its natural and processed forms, such as porridge, cake, etc. Manioc, though, is the staple and most traditional food. It is consumed in natural form and in various processed forms, such as bread, flour and tapioca, but above all the tuber is used in the production of special drinks such as pajuaru, saboruá and caxiri, served day-to-day (very often with meals) and during ceremonies.

The Wapishana also depend on hunting and fishing, which are increasingly undertaken with the use of non-indigenous tools, such as hooks, fishing nets and guns. Nonetheless, particularly in the malocas further away from the urban centres, such as Pium, for example, people still use arrows and spears for these activities. Gathering and extractivism of plant products, such as bacaba, burity and assai palm trees and so on, are equally important activities.

Another important activity is farming, particularly collective cattle breeding, which is coordinated by the tuxaua (leader) of each maloca and intended to provide the community as a whole with resources. Sheep and pig breeding by individual nuclear families are also common.

Cosmologies

Cosmogony and the creative force of speech

In the beginning, say the Wapishana, “when the sky was close, everything spoke, it was puri,” magic. Sky and earth where undifferentiated at that time, so too the beings who inhabited them since their all spoke just one language.

The original world was above all mutable and the power to shape it was found in words: “In the past, people spoke and things changed. Everything now is already made.” Effective and creative, words provoked constant transformations, which gave the world the appearance that it still retains today: waterfalls, rivers and mountains that were created in verbal battles between the demiurges.

The past, though, is irremediably lost. The world as we know it today is the inverse of this original plasticity; the world is ready and ‘hard,’ resisting human intervention. This, the Wapishana explain, is because speech lost its productive power – originally a property of all speech. Its magic today is only manifested within ritual discourse.

Today’s world is the result, therefore, of the rupture of a primordial order, a rupture that differentiated time and space and led to the emergence of the different species. This speciation, in turn, was based on an uneven distribution of speech: it was lost by many species, the basic reason for them turning into other species – or, as the Wapishana prefer to say, qualities – making articulate speech an attribute almost exclusive to humanity, distinguishing them from the other beings who populate the world. Thus, from the Wapishana viewpoint, articulate speech is what makes humans human.

Udorona, the vital principle

Udorona is a vital principle found in speech, blood and breathing; proof of this, the Wapishana say, is that when we die we become white and cold.

In contrast to breathing and speech, blood is a transmitted and shared component of the person. For the Wapishana, blood is obtained through transmission: we receive it from our father and mother in equal proportions. It is also shared: an individual’s siblings, parents and children possess the same blood. The limits of consanguinity are defined by this group, limits explicitly referred to as sõtokon, ‘my tips:’ “a tip is like a shoot, born from the same plant.”

Breathing is a personal component of the soul, acquired only when we leave our mother’s womb and breathe in for the first time. To some extent, breathing is associated with the value of speech, an association that becomes clearer in the context of magic: blowing (magic) and speaking are homologous acts, which provoke the same effect of enchantment, since both are aspects of the soul.

Blowing and speaking indicate that the basic attribute of the soul is lightness. The soul – blowing and speech combined in magic – can still restore the creativity of the original speech in humans, its power to transform the world.

Speech, in turn, from the Wapishana viewpoint, is intimately connected to the soul. Its existence in humans singularizes them and prevents them from losing their identity among the things of the world. Another indicator of human life is the hoarse inaudible murmuring of the dead, whose intelligibility is synonymous of death.

Speech is also a key principle of reason. Small children are called madoronan, a term whose literal translation is ‘soul-less,’ because they do not yet speak. For the Wapishana, this also implies that children lack discernment – “children have no judgment” – a fact that excuses their misbehaviour.

Both speech and discernment develop during the process of the individual’s socialization, culminating in their full sociability. Hence, at its peak, the faculty of speaking completes the adult person as someone capable of dialoguing with his or her peers.

The term madoronan also applies to those who are out of control, whether drunk, or consumed with anger or rage, resentment or passion: such people act erratically and avoid speech and dialogue.

Speech is a strictly personal principle: “To form a child, the parents contribute the blood; breath and speech come from the child itself. We teach the child how to speak, but our udorona cannot make the other speak.”

The ability to speak has to be developed socially: children are taught to speak. Although this fact may seem obvious and commonplace to ourselves, it is highly symbolic to the Wapishana given the equivalence they make between speech and the soul: teaching a child to speak is a process of humanization, only attained with full sociability.

In addition to being personal, speech is an accumulative principle that only reaches plenitude in old age when, for the Wapishana, we are more soul than body. This conception includes knowledge, a necessary component of oratory skill; speaking well is the corollary of wisdom, which only exists in direct proportion to the soul.

In sum, for the Wapishana, speech – as a correlate of the soul – is the central value in the definition of the human.

Refined thinkers, the Wapishana do not postulate that the soul inhabits a bodily container, or even that it is located – in an image to which we are accustomed – in a specific part of the body, such as the heart or head. Udorona is the vital principle properly speaking, a force that moves and animates us. Indissociable from the body, udorona is the dynamic principle that confers movement, autonomy and will. Its existence is also visible in the strongest shadows cast by ourselves in the sunlight.

Death

Death involves the complete interruption of breathing, the pulse and speaking. This may occur without being definitive when a person faints, falls into an alcoholic coma or otherwise loses consciousness, all events designated by the same verb, maokan, to die. At death, “the soul leaves,” udorona umakon naa, or, in more eloquent form, umashadan, “somebody fell silent.”

The post-mortem fate of the dead is not particularly elaborated: on the contrary, when questioned on the subject, the Wapishana merely reiterate that “nobody knows where the udorona goes.” Death does not represent the end of the udorona, but the end of its individuated existence; what does not persist at death is the personality. Although some people believe that udorona possesses an existence after the person’s terrestrial life, this is an identity-less existence that induces the gradual estrangement of the dead from the living.

Notably, only shamans have a distinct post-mortem fate: they remain in a tree called Toronai, which exists high above in the sky or on the top of the highest and most inaccessible mountains, where the shamans marry again and may have children.

Once the udorona leaves the body, death produces two other aspects that, though different, are both euphemistically called porawaru, the wind. Udikini, in contrast to the vital force constituted by udorona, is the weakest shadow that we cast in the sun. The term udikini applies to portraits and television images; like the latter, udikini are no more than a pale shadow that occasionally appears to the living: “you recognize it, but it is no longer alive, it has already died.” Innocuous to the living, an udikini merely produces noises in spots that it once frequented. Sometimes it hides in whirlpools but it can usually be perceived in the house in which it lived since it tries to stay close to its former terrestrial belongings.

It may be suggested that an udikini, defined by the Wapishana as a shadow, is the memory that the dead person carried of his or her belongings during life, but also, conversely, the memory of the dead person evoked by the objects that were once his or hers. This memory gradually wanes as the objects acquire new uses and owners: in about six months, the Wapishana say, the udikini disappears.

The living also try to rid themselves of the memory of someone’s face and history: this comprises the ma'chai, a term that refers both to the corpse and to its spectre. “Udorona,” the Wapishana say, “nobody knows where it goes; what comes back is the ma'chai.”

Ma’chai, the corpse and spectre released by the latter, is an extremely dangerous, indeed lethal, being that possesses the terrible power of making everything putrefy. The pain of mourning and the memory of the dead make the living vulnerable to ma’chai attacks. To avoid the latter, forgetting is imperative. Nobody sees it, nobody hears it, nobody recognizes it. The erasure of its memory is the prerequisite for the continuation of life. As the Wapishana explain, resorting as ever to the plant world for comparison: “look at cotton, nobody remembers the plant from which it was plucked.” Collectively, released from their individual form, the dead become the ancient ones and, with the temporal distance produced by forgetting, no longer represent a threat to the living.

Funerary practices

Burial and other mourning activities involve the dead person’s kingroup, though there is no clear separation of roles between affines and consanguines; when asked, even unrelated neighbours may collaborate.

These measures are undertaken during the wake. Usually this remains in the small shelter outside the house, wrapped in the dead person’s hammock or completely covered by a sheet.

There are no ostentatious displays of emotion; on the contrary, the lament of the person’s kin is low-pitched and restrained. The village’s other residents may come to ‘spy on the body,’ commenting in low voices about the cause of death. Children, mothers with babies and sick people take no part in the wake.

In the past, the body was buried in the dead person’s own house, which was then abandoned by the kin. This practice has fallen into disuse, though, with the implantation of a cemetery close to the village.

The threat of the ma’chai hovers over the village for the next few days: people avoid being alone and small lanterns are left burning all night: light and human company directly oppose the dark solitude of a grave.

Children must be protected since they are more vulnerable than adults to the proximity of the ma’chai: watching burials, following funeral processions or even stepping accidentally on the tracks left by coffins causes their bellies to swell and provokes dysentery, signalling a process of decomposition analogous to the rotting of the corpse.

Consanguines are most at risk of being captured by the ma’chai. Various cases exist of people dying immediately after the death of parents, children or spouses. However, more than victims, consanguines are themselves vectors of contagion since people in mourning are deemed to enter a state of dipshan, ‘state of putrefaction.’ The corpse’s putrefaction affects them too: “it’s a mystery, why we haven’t died yet despite being rotten already.”

Close kin must bathe with a mixture of aromatic herbs, fishing poisons and dry manioc leaves, which, like the process of purifying the house, neutralizes the dipshan odour that they carry, cutting their connections with the ma’chai. As the most prominent symbol of mourning, the bathing may cease after around a month when all that is left of the corpse is bones, which exhale nothing and are not therefore dangerous.

Shamanism

The term for shaman is marinao, while his songs are called marinaokanu. These shamanic songs are also described as upurz karawaru, which the Wapishana translate as “the marinao’s cord.” The shaman chants these songs accompanied by a rhythm beaten with a sheaf of ingá or pau-tipiti leaves, enabling him to ‘ascend,’ that is, leave the body and allow other beings – especially dead shamans – to manifest themselves through his own body while his soul – udorona – visits the invisible inhabitants of the mountains and other locations. The marinao’s vital principle remains linked to his body through this song-cord, meaning that shamans at war will try to cut the cord of their adversaries.

A marinao without a repertoire of upurz karawaru – or a cord, in other words – is called chanaminuru, a ‘bad’ shaman, who uses the rainbow to ascend. During a shamanic session, the upurz karawaru songs are interspersed with dialogues established between the beings manifested through the shaman and his assistants. Very often these beings express themselves in foreign languages, imbuing shamanic discourse with a degree of esotericism.

The fundamental point of a shaman's initiation involves the incorporation of a particular category of magic plant – wapananinao – through ingestion via the nostrils and mouth. These plants that possess the gift of song. Marinaokanu are, therefore, chants of wapananinao plants that the shaman keeps within himself and that are already mixed with his own nature.

In a curing session, the song is directed towards the sick person’s soul, as well as the entity responsible for capturing it and causing the sickness, and intended to persuade the soul to return to the body. The songs do not describe the battle for the soul: they are themselves part of the battle.

Chants

The Wapishana gloss puri as ‘prayer’ or ‘remedy.’ These are chants – formulas – that have power over the tangible and intangible world. They are used to treat illnesses – which invariably result from the aggression of supernatural beings – as well as ensuring success in hunting, fishing, agriculture and almost all other quotidian activities, both male and female.

Puri are also used to cancel the harmful effects of the failure to observe reclusion properly after deaths, births and menstruation, or to make game and fish edible, pacifying their principle, the ‘grandmothers’ of each species. Puri are also used to influence the will of other people, in particular in seduction and vengeance.

In principle, the knowledge and use of puri formulas is accessible to everyone. The size of repertoires varies, however: the most vast are recognized as attributes of specialists, the popazo, ‘healers,’ although their acquisition does not depend on any requirement other than a personal interest in this apprenticeship. Adults generally possess a repertoire, albeit limited, for the domestic treatment of the grandchildren's illnesses.

The puri formula possesses a fixed structure that does not permit variations: a short formula that frequently makes use of parallelism and whose efficacy in theory relies on word-for-word memorization and repetition.

The chants are the language of the beings that originally populated the world when speech has a creative power. Following the rupture of the original order, the Wapishana claim, these beings transformed into puri. Hence their paradox: imprisoned in the chant, the speech of all these beings can only be manifested today through the human voice.

Effected through speech and blowing, chanting is understood as the soul in action. The Wapishana explain: “when we use puri, we blow because it’s calling through the mouth, our wind is blowing, it’s our speech. Udorona is calling, just like god.” This property provides the power to create or change realities.

Access to knowledge

Aona puaitapan amazada – “you don’t know the world” – is the response invariably received by younger people when they try to give their opinion on topics considered serious or, at they very least, beyond their reach. The phrase aptly summarizes how the Wapishana conceive the acquisition of knowledge. Amazada, the world, is a notion that encompasses space and time, lending the phrase a double sense: on one hand, it means someone who has not journeyed through the world enough to know it; on the other, it means someone who has not lived long enough to know it.

Visiting places beyond one's home village is an important part of acquiring knowledge. Unmarried young men typically travel to other villages in Brazil or Guiana, or to work at the farms and mines scattered throughout the Wapishana territory; they frequently bring back a wife and a knowledge of spectacular cures, as well as an impressive repertoire of narratives learnt at night around bonfires.

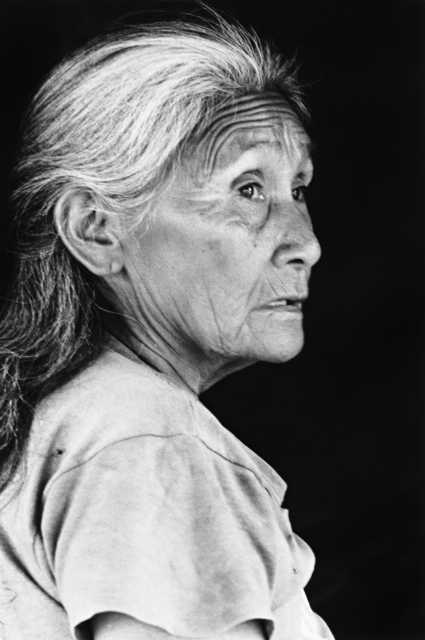

However, for the Wapishana, the access to knowledge and wisdom is primarily associated with time and age: older people are the ones who have inevitably accumulated knowledge through experience.

The association of knowledge with age does not imply that younger people lack repertoires of narratives; on the contrary, prepubescent girls and boys who almost always remain discrete and silent while older people recount stories of the past are later able to repeat them or even add their own variations. But while they may know a particular repertoire, young people do not feel authorized to narrate it since this authority is socially recognized as an attribute of age.

Older people, “those who know histories,” are called kwad pazo, a term that the literate Wapishana translate as historians; in the context of the Catholic church service, the term is also given to the person who interprets the bible reading. Others, also associating the term with writing, use the metaphor of ‘library of the villages’ to refer to these older people, thereby recognizing them as holders of a specialized knowledge.

It is important to note a crucial difference in relation to other Amazonian societies: knowledge among the Wapishana, associated with age, is an open channel accessible in theory to everyone, given that aging is an inescapable process that inexorably affects all of us. Conceiving knowledge as a necessarily accumulative process, the Wapishana deem a full adult capable of being a kwad pazo, which does not mean that everyone is; older people have the potential, but developing it is not the norm.

In sum, the kwad pazo is a wise person and wisdom is an inevitable derivative of life experience. The kwad pazo are sometimes called, or jokingly call themselves, “remains of kotuanao” [the ancient ones], since as well as being narrators, they are also co-participants of a past of which younger people have no direct memory or experience.

For the Wapishana, too much knowledge causes premature aging and for this reason young people should not try to acquire it lest their become grey-haired or, in an extreme case, mad. Premature aging and madness are the motives most frequently alleged by young men for not learning non-colloquial discursive practices.

As a corollary of old age, knowledge increases as physical strength declines, in particular sexual and reproductive activity. For the Wapishana, this is explained by the fact that the acquisition of knowledge, linked to the sphere of the soul, is in inverse ratio to the reproduction of bodies. Among young people, women are more linked to the sphere of the body compared to older people. In the access to knowledge, therefore, the age criterion clearly subsumes that of gender: old age distances men and women from the body in equal measure, making them more soul than body.

Life phases

The Wapishana do not display age groups or rigidly demarcate rites of passage, though, despite not being heavily institutionalized, they obviously identify socially relevant phases in an individual’s life history.

Children are indiscriminately referred to by a single term, koraidaona. In puberty, “when the voice changes,” a young man becomes designated by the term tominaru, an existential state only left at marriage when he then becomes a daionaoara, a term that simultaneously means man and husband. The birth of children consolidates adulthood. However, only when his children marry and he becomes a father-in-law will he effectively achieve a mature age and respectability, while full adulthood comes with the birth of the first grandchildren.

The same applies to women with the difference that female puberty is distinguished by intermediary phases that more emphatically mark the girl’s entry into sexual and reproductive life: when her breasts begin to grow, the girl is called kadineibi, becoming kashinaru at her first menses; at the height of puberty she is called mawisse, which designates a young and beautiful woman. This is her status until the birth of her children, since mawisse indicates a woman who has never given birth. From then on, women are classified by their children’s marriages and grandchildren, just like men.

Notes on the sources

Ethnographic description of the Wapishana began with Henri Coudreau (1887-1888) in the 1880s, a period in which the French traveller explored the region east of the Branco river, the valleys of the Tacutu and Rupununi rivers, eventually reaching the Trombetas river. He therefore visited the Wapishana and Atorai territories in the Lua uplands and those of their Taruma and Wai-Wai neighbours as far as Pianakoto territory. Seriously ill with a series of fevers, Coudreau stayed at the Malacacheta village for eleven months, acquiring a then unimaginable familiarity with the language and daily life of the Wapishana. Coudreau is therefore responsible for the first detailed description of these Indians and their territory.

In 1918, the American ethnographer William Curtiss Farabee published The Central Arawaks, the result of a one year expedition to the Rupununi district (in what was then British Guiana) under the sponsorship of the University of Pennsylvania Museum. The work, following the standard model of the period, was organized into topics covering the mythology, social organization, material culture and language of the region’s Arawakan peoples, namely the Wapishana, Atoradi and Mapidiana. The monograph was harshly criticized by Walter Roth, then considered one of the most prominent scholars of the colony’s indigenous peoples. Roth, a colonial officer, had dedicated years to collecting ethnographic data on the Guianese peoples.

Later, in the 1940s, the anthropologist Lucila Hermmann (1946) undertook a study of the Wapishana on the Brazilian side: she based her work on data gathered by the Benedictine priest D. Mauro Wirth, who worked as a missionary among the Wapishana during the 1930s. She examined kinship, ritual and the political system, the latter from the viewpoint of the changes introduced by contact.

After Herrmann’s studies came a few brief articles by E. Soares Diniz (1967) and Orlando Sampaio Silva (1980; 1985), based on research from the 1960s and focusing invariably on the relations surrounding contact.

The American anthropologist Nancy Fried carried out field research among the Wapishana in the 1980s. However, the divulgation of her findings seems to have been confined to a single article on Wapishana ethnic identity (1985).

From 1988 to 1994, the anthropologist Nádia Farage conducted documental research and fieldwork among the Wapishana. Her work, focusing on the theme of Wapishana rhetorical practices, resulted in a thesis defended at the University of São Paulo in 1997 and in various articles on the ethics of speech and discursive genres among the Wapishana. The author’s thesis continues to be the most up-to-date ethnographic description of this people.

Among the more recent works are the MA dissertation by Giovana Acácia Tempesta (2004) on reclusion practices among the Wapishana and the Makuxi; the Ph.D. thesis by Carlos Alberto Borges da Silva (2005) on the Rupununi Uprising, which occurred in 1969 in the south of Guyana; and the doctorate by linguist Manuel Gomes dos Santos, which resulted in a Wapishana grammar.

In Guyana, studies were undertaken by T. McCann (1972) and more recently by Janette Forte and Laureen Pierre (1990). McCann’s study, an unpublished report produced for funding agencies, concentrates theoretically and practically on the incorporation of the Wapishana into national society. Carried out a short while after the 1969 Rupununi Uprising in which the Wapishana, supporting local white farmers, revolted against the central government, the study focalizes on what was effectively the government’s priority during this period: the political control of the Wapishana through the imposed sharing of a nationality.

The brief essay by Forte and Pierre (1990), the result of a survey of the sociological situation of the Rupununi district in 1989, follows the outlines indicated above, looking to ascertain the degree of integration of the Wapishana, two decades after the uprising, considered a watershed in the region's interethnic relations.

Sources of information

- ALMEIDA, Tânia Mara Campos de. O levantamento e a vistoria das ocupações de não índios: o caso da Terra Indígena Barata/Livramento (RR). In: GRAMKOW, Márcia Maria (Org.). Demarcando terras indígenas II: experiências e desafios de um projeto de parceria. Brasília: Funai/PPTAL/GTZ, 2002. pp.151-68

- ANDRELLO, Geraldo L. Relatório sobre a Terra Indígena São Marcos: histórico e situação geral. São Paulo: Eletronorte, 1998. 120 p.

- AVILA, Thiago Antônio Machado. Biopirataria e os Wapishana: análise antropológica do patenteamento de conhecimentos indígenas. Brasília: UnB, 2001. (Monografia de Graduação)

- CADETE, M. C. Dicionário Wapichana-Português/Português-Wapichana. São Paulo, Loyola. s/d.

- CENTRO DE INFORMAÇÃO DIOCESE DE RORAIMA. Índios de Roraima: Makuxi, Taurepang, Ingarikó, Wapixana. Boa Vista: Diocese de Roraima, 1989. 106 p.

- CIR; CPI-SP. Parecer sobre o relatório de impacto ambiental da hidroelétrica de Cotingo. São Paulo: CPI, 1994. 37 p.

- ELETRONORTE. Interligação elétrica Venezuela-Brasil: processo de negociação com as comunidades indígenas das TIs São Marcos e Ponta da Serra. s.l.: Eletronorte, 1997. 69 p.

- FARABEE, W. C. “The Central Arawaks”. In: The University Museum Anthropological Publications, vol. IX. Philadelphia, University of Pennsylvania, 1918.

- FARAGE, Nádia. “Rebellious Memories: The Wapishana in the Rupununi Uprising, Guyana, 1969”. In: WHITEHEAD, N. L. (Ed). Histories and historicities in Amazonia.University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln and London, 2003.

- --------. “Instruções para o presente: os brancos em práticas retóricas Wapishana”. In: ALBERT, Bruce; RAMOS, Alcida Rita (Orgs.). Pacificando o branco: cosmologias do contato no Norte-Amazônico. São Paulo: Unesp, 2002. pp. 507-31.

- --------. “Os múltiplos da alma: um inventário de práticas discursivas wapishana”. In: Revista Itinerários. Araraquara, 1998, n. 12, pp. 111-123.

- --------. “A ética da palavra entre os Wapishana”. In: Rev. Bras. de C. Soc., São Paulo: Anpocs, v. 13, n. 38, out. 1998.

- --------. As flores da fala: práticas retóricas entre os Wapishana. São Paulo: USP, 1997. 298 p. (Tese de Doutorado)

- --------. Funai x Milton de Barros e Epitácio Andrade Lucena (laudo antropológico processo 92.0001641-3). s.l.: MPF, 1994. 78 p.

- -------- & SANTILLI, P. “Estado de sítio. Territórios e identidades no vale do rio Branco”. In: CARNEIRO DA CUNHA, M. (org.) História dos Índios no Brasil São Paulo, Cia. Das Letras/Fapesp, 1992.

- --------. As muralhas dos sertões: os povos indígenas no Rio Branco e a colonização. Campinas: Unicamp, 1986. 469 p. (Dissertação de Mestrado)

- --------. “Os Wapixana nas fontes escritas: histórico de um preconceito”. In: BARBOSA, Reinaldo Imbrózio;

- FERREIRA, Efrem Jorge Gondim; CASTELLON, Eloy Guillermo (Eds.). Homem, ambiente e ecologia no estado de Roraima. Manaus: Inpa, 1997. p. 25-48.

- FORTE, Janette. The material culture of the Wapishana people of the South Rupununi savannahs in 1989. Turkeyen, Georgetown: Amerindian Research Unit/University of Guyana, 1992. 92 p.

- FRANCHETTO, Bruna. Levantamento sócio-lingüístico nas malocas Napoleão (Makuxi) e Taba Lascada (Wapichana). Boa Vista, 1988.

- HERRMANN, L. “Organização social dos Vapidiana do território do rio Branco”. In: Sociologia, 1946, vol. VIII, no. 3: 282-304.

- --------. “Organização social dos Vapidiana do território do rio Branco (continuação)”. In: Sociologia. 1946, vol. VIII, no. 4: 203-215.

- MELO, Maria Auxiliadora de Souza. Metamorfoses do saber Macuxi/Wapichana: memórias e identidade. Manaus: UFAM, 2000. 170 p. (Dissertação de Mestrado)

- MIGLIAZZA, E. C. 1980 Languages of the Orinoco-Amazon basin: current status. Antropologica 53:95-162. Caracas, Fundacion La Salle.

- --------. Languages of the Orinoco–Amazon Region: current status. In: South American Indian Languages restropect and prospect. Ed by Harriet E. Manelis Klein and Louisa R. Stark. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1985.

- PENGLASE, Ben. Brazil: violence against the Macuxi and Wapixana indians in Raposa Serra do Sol and Northern Roraima from 1988 to 1994. New York: Human Rights Watch/Americas, 1994. 30 p.

- REPETTO, Maxim. Roteiro de uma etnografia colaborativa: as organizações indígenas e a construção de uma educação diferenciada em Roraima, Brasil. Brasília: UnB, 2002. 297 p. (Tese de Doutorado)

- RODRIGUES, Aryon Dall’Igna. Línguas indígenas: 500 anos de descobertas e perdas. D.E.L.T.A. 1993, n. 9, 83-103.

- --------. Línguas brasileiras - para o conhecimento das línguas indígenas. São Paulo: Loyola, 1986.

- SANTOS, Manuel Gomes dos. Uma gramática do Wapixana (Aruák) - aspectos da fonologia, morfologia e da sintaxe. Campinas: Universidade Estadual de Campinas, 2006. (Tese de doutorado)

- --------. Os segmentos sonoros e a silaba wapichana: uma perspectiva não-linear. Florianópolis: UFSC, 1995. (Dissertação de Mestrado)

- SILVA, Carlos Alberto Borges da. A Revolta do Rupununi: uma etnografia possível. Campinas: Universidade Estadual de Campinas, 2005. (Tese de doutorado)

- SILVA, Orlando Sampaio. Notas sobre algunos pueblos indígenas de la frontera amazónica de Brasil en otros paises de sudamerica. In: JORNA, P.; MALAVER, L.; OOSTRA, M. (Coords.). Etnohistoria del Amazonas. Quito: Abya-Yala; Roma: MLAL, 1991. p. 117-32. (Colección 500 Años, 36)

- SIMONIAN, Lígia Terezinha Lopes. Direitos e controle territorial em áreas indígenas amazônidas: São Marcos (RR), Urueu-Wau-Wau (RO) e Mãe Maria (PA). In: KASBURG, Carola; GRAMKOW, Márcia Maria (Orgs.). Demarcando terras indígenas: experiências e desafios de um projeto de parceria. Brasília: Funai/PPTAL/GTZ, 1999. pp. 65-82.

- SOUZA, Marcos Alves de. Relatório circunstanciado de identificação e delimitação da Terra Indígena Muriru-RR. Brasília: PNUD/PPTAL/Funai, 1998.

- WIRTH, D. M. “A mitologia dos Vapidiana do Brasil”. In: Sociologia. 1946, vol. VIII, no. 4: 257-268.

- --------. “Lendas dos índios Vapidiana” In Revista do Museu Paulista.São Paulo, 1950, vol.4.