Waiwai

- Self-denomination

- Where they are How many

- Linguistic family

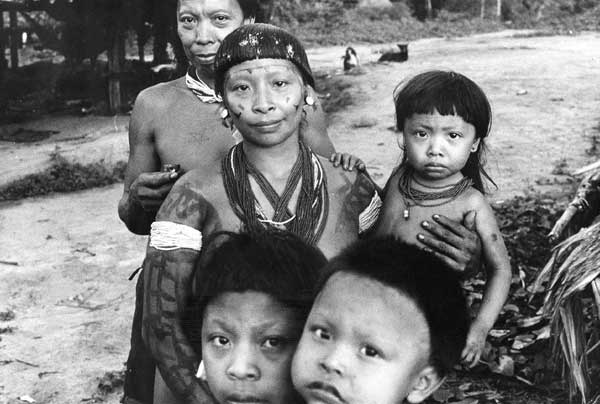

The indians that call themselves and are known as Waiwai are to be found scattered over large parts of the region of the Guianas. In the main they are members of the Karib language family. The group was constituted through historical processes of exchange and networks of relationships in the region. Within these networks they have traditionally been recognized as specialists in the supply of sophisticated manioc graters, talking parrots and hunting dogs. They are famous to today as great travellers for their expeditions in search of the ‘unseen peoples’ (enîhnî komo).

Names and co-residents

According to the ethnographic bibliography of the region of the Guianas, and in a similar way to various other Amerindian collective names, Waiwai ethnogenesis is made up of a set of relationships that includes conceptions about those communities that call themselves Waiwai and the conceptions of these communities about themselves and others. The term ‘Waiwai’ is used here in the sense attributed to it by those indians who identify themselves and are currently identified by the term; in other words, the term is understood not to correspond to a single substantive ethnic unit existing as such, but rather as a coinage that fulfils both political and intellectual purposes.

Many indians currently living in Waiwai communities identify themselves and are identified by others by less encompassing names, as in the cases of the Hixkaryana, Mawayana, Karapayana, Katuena e Xerew (or Xerewyana, whereby ‘yana’ is the collective designation), amongst others. It was (and continues to be) the famous expeditions of the Waiwai in search of the ‘unseen peoples’ (enîhni komo) that enabled (and continue to enable) widespread exchanges with other peoples as part of a wide regional network. It is as a result of this network that there occurred (and continue to occur) numerous marriages and invitations to whole families to move to live in the Waiwai communities, as happened in the cases of the indians referred to above.

After 1950, when the Waiwai allowed the presence of the Unenvangelized Field Mission, currently operating in conjunction with the MEVA (Missão Evangélica da Amazônia), these expeditions could count on both the material support (availability of outboard motors and even the occasional use of the mission plane) and immaterial support (a discourse of evangelical salvation) of this mission. One of the results of permanent contact with the mission, and over time with other non-indian actors such as Funai and Funasa, as well as sporadic contacts with researchers and the riverbank population amongst others, was that these used the term ‘Waiwai’ to describe not just the Karib language predominantly spoken by these indians but also as a way of referring to the collectivity as a whole. They would thus speak of the ‘Waiwai’ (or ‘Wai-Wai’) communities of such and such a place.

Language

A The Waiwai language, a member of the Karib language family, constitutes the main language used by the inhabitants of the Waiwai communities. Until recently other languages were also spoken in these communities, by the kinship groups of other indians who had intermarried with the Waiwai or who had migrated en masse to reside with the Waiwai during the phase of centralization in large villages in the period 1950 to 1980.

In addition to this dominant language, which all learned, in 1980 there were still kinship groups speaking other Karib languages (Katuena, Hixkaryana, Xerew, Karapayana) or those of the Arawak language family (Mawayana, Wapixana). There were also individuals whose mother tongue had become extinct or that was almost forgotten (Parukoto, Taruma, Cikyana), as well as others from neighbouring peoples speaking other languages (Makuxi, Tiriyó, Atroari) who had come to live with their Waiwai spouses. Nowadays the majority of young people born in the Waiwai communities speak only this dominant language.

In the 1990s some Waiwai communities who had become too large to support their population as a result of the scarcity of resources, for example the community of Mapuera, began a process of decentralization. Since then many of the peoples who had been living among the Waiwai have begun returning to their areas of origin and have founded new villages, where their own language is now dominant. This is the case of the Hixkaryana, Karapayana, Katuena and Xerew. The Mawayana, reduced to half a dozen survivors still are able to speak their mother tongue, continue to live among the Waiwai and the Tiriyó.

Such processes of centralization and decentralization help to explain why the Waiwai language has become the regional lingua franca. It is the principal language spoken in the regional General Assemblies that began to be organized after 2003.

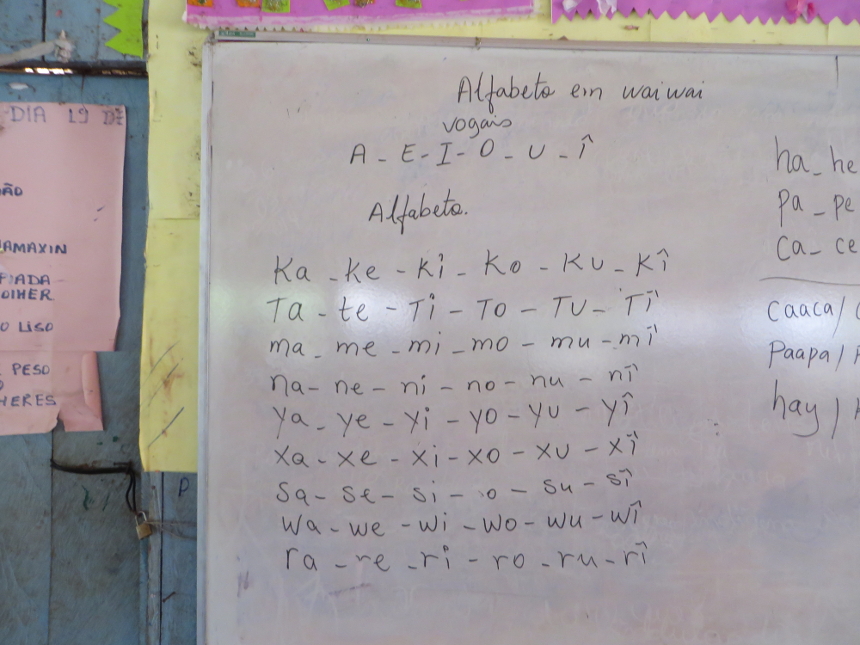

Mission and writing

Following their arrival in 1949, the Hawkins brothers, North American missionary linguists from the Unevangelized Fields Mission (UFM), learned Waiwai, published articles analysing its structure, and developed a spelling system for teaching the Waiwai (and the other peoples who had joined these) to read and write. Robert Hawkins prepared language lessons for other missionaries and translated the Bible into Waiwai [see the article Current relations with non-indians]. Until the mid-1980s, missionary teachers taught written Waiwai (and a little Portuguese) to children in the schools and trained the most interested students to be monitors. There is currently only one missionary who still teaches (in Mapuera), although some of the monitors she trained are now teaching in their own communities. In other communities, the teachers are Makuxi or neo-Brazilians, speaking and teaching only Portuguese; while in yet others, the children are not taught any written language at all, for lack of schools.

The first Waiwai to be trained as teachers by the states of Roraima and Pará are starting to teach the indigenous language in a few communities but, with the exception of religious literature, there is a lack of written material in Waiwai. The majority of the men speak a little Portuguese, learned more during trips to town than in school, some fluently, whilst the majority of the women understand only a little, or none at all. This situation is however slowly changing.

Location and population

The processes of centralization and decentralization were important both for settlement patterns (heavily based around the autonomy of the local groups, as well as the prevailing political situation, involving permanent contact and accommodation with non-indians [see the article Relations with non-indians]) and for the concentration and dispersal of the population at different historical moments in the region spanning Essequibo river in Guyana [see the box: Waiwai in Guyana], the Anauá and Jatapuzinho rivers in Roraima, the Jatapu and Nhamundá rivers in Amazonas, and the Mapuera river in Pará.

The bibliography reveals that over the last fifty years constant contact with non-indians – initially with the North American missionaries of the Unevangelized Fields Mission (UFM) and subsequently with the Missão Evangélica da Amazônia (MEVA), agents of Funai and Funasa, as well sporadic contacts with researchers and riverside populations – began a process of concentration of the communal houses that previously were spread out along both sides of the Serra do Acarai, the frontier between Brazil and Guyana. However the appearance of new settlement patterns promoted by the missionaries, and which resulted in large villages such as Mapuera, did not mean that the autonomy of the local groups ceased to exist or was no longer important, quite the opposite. Evidence suggests that the process of centralization is now being succeeded by a new process of re-dispersal, as shown by the migrations and establishment of new Waiwai communities such as Catual, Soma, Samaúma, to cite just a few of the many examples.

The officially recognized territory consists of the following three Terras Indígenas, covering parts of the states of Amazonas, Pará and Roraima:

- TI Nhamundá-Mapuera (Pará), totalling 1,049,520 hectares and 2,218 pessoas in 2005;

- TI Trombetas/Mapuera (Amazonas/Roraima/Pará), totalling 3,970,420 hectares and 500 people in 2005;

- TI Wai-Wai (Roraima), totalling 405,698 hectares and 196 people in 2005.

The waiwai in Guyana by Stephanie Weparu Alemán, anthropologist, Iowa State University The Waiwai population in Guyana currently occupies two villages in the southern part of the country. The first of these is the village of Masakinyari (‘the place of the Mosquito’), located in the far south on the upper reaches of the Essequibo river.

The number of its inhabitants varies between 130 and 170, depending on the season of the year, extensive inter-village visits and the constantly changing number of Wapixana families. The inhabitants of Masakinyarï keep up close contact with the Waiwai communities in Brazil located on the other side of the Serra de Acaraí. Up to the 1950s there were many small Waiwai villages and villages of other groups along the upper Essequibo. The reason for many of these coming together to form larger villages was the presence of the Unevangelized Fields Mission, responsible for founding the village of Konashenay (‘God loves you here’).

This village grew to the point of having 500 inhabitants before the population broke up again into smaller groups. The current village of Masakinyarï includes members of the village of Sheparyimo (village of the ‘Large Dog’), which existed from the beginning of the 1970s to the mid-1980s, and of the remaining population of the village of Akotopono (village of the ‘Large Old Weapon’), which existed from the 1980s until the creation of the new village of Masakinyarï in 2000. Shortly before the creation of the new village many families, including nearly all the resident Wapixana, moved to a location on the Kuyuwini river near to a place known as the Parabara landing strip.

A trail from this landing strip to the Rupununi savannahs further north enabled better access to the Wapixana and Makuxi villages, as well as to the towns of Lethem and Bon Fim and to the Brazilian city of Boa Vista. This village at Parabara contains approximately 70 inhabitants, half of which are Wapixana. However the village has a Waiwai name, Erepoimo (village of the ‘Great Firer of Pots’), which was the name of a small Waiwai encampment on the upper Essequibo in the 1940s and 1950s. Both villages maintain family ties with members of Waiwai villages in Brazil.

For this reason there is virtually no cultural difference between the villages on both sides of the frontier, apart from their differing relations with the respective Brazilian and Guyanese states. The Guyanese of the coast generally refer to the Waiwai villages in the extreme south of the country as ‘Gunn’s Strip’, in reference to a landing strip located in a small savannah in this region, or as ‘Konashen’ (or ‘Kanashen’), in reference to an old missionary village.

History of contact

The difficulty in determining what are in fact the earliest references to the groups that would later come to constitute the current Waiwai communities resides in the fact that, as is common throughout the indigenous Amazon, the names attributed to different indigenous groups vary greatly over time. One of the earliest pieces of information, although no more than a simple reference, dates from the 17th century (R. Harcourt 1603 [1928]). Another dates from the 18th century (Sanders 1721 in Ijzermann 1911 cited by Bos 1985).

During the 19th century three travellers mentioned the Waiwai. The first was the British geographer Robert Hermann Schomburgk who travelled in British Guiana and the Orinoco river region from 1835 to 1839 and again in 1843. He encountered the Waiwai on both sides of the Brazil-British Guiana border, in two villages to the south of the Mapuera river and one to the north of the Essequibo, separated by the Serra Acaraí and at a distance of two days walk from each other. The traveller judged the population of these thee villages to be 150 people. Schomburgk’s reports contain several remarks that suggest the existence of an extensive trading network among the different groups of the region. Unfortunately direct data on the Waiwai are scarce. Indirectly however, Schomburgk learned from neighbouring groups such as the Mawayana and the Taruma that the Waiwai were renowned in the region for their skill in growing cotton and in hunting, and above all for their hunting dogs and their sought-after manioc graters.

The next traveller, the British geologist Barrington Brown (1876, 1878), encountered the Taruma, Wapixana and Mawayana indians in November 1870 returning from a trading expedition to the Waiwai. Having no contact with non-indians, the Waiwai obtained manufactured goods such as tools, cloth and beads by trading their manioc graters and hunting dogs with these neighbouring groups. From this indirect source, Barrington Brown earned that the Waiwai were found at that time only on the south side of the Acaraí range.

In 1884 the third traveller, the French geographer Henri Coudreau (1899), encountered the Waiwai on the Mapuera, in the region south of the Acaraí range, while the area to the north was occupied only by the Taruma. Coudreau estimated the population of the ‘Ouayeoue’ (Waiwai) at approximately three to four thousand people in seven villages of 300 inhabitants each. Others consider this number exaggerated (Fock 1963, for example). Like Schomburgk, Coudreau also reports the existence of a broad trade network involving the Waiwai and several other groups in the region. He refers to trade links between the Waiwai and the Wapixana, Atorai and Taruma to the north, to the east with the Pianokoto (Tiriyó), and on the Trombetas-Mapuera rivers with the Mawayana and the Xerew, amongst others. After his death, his widow Olga Coudreau (1900) kept up the expeditions. Unlike her husband, who wrote that the Waiwai and the Mawayana did not possess any European goods, she describes their skill in bartering for prized articles such as beads, mirrors, machetes, combs and axes.

At the end of the 19th century the Waiwai were still in contact with the Taruma indians and had also established peaceful relations with the Tiriyó of the Trombetas-Paru de Oeste region, but were at war with the peoples inhabiting the middle Mapuera, belonging to the Parukoto group (Fock 1963: 5). The area occupied by the Waiwai therefore corresponded to the region of the headwaters of the Mapuera, bounded to the north by the Serra Acaraí. To the south of this territory lived other groups, nowadays integrated into the Waiwai after having gradually migrated northwards, retreating in the face of the extractive frontier in the Trombetas basin. From north to south there were the following peoples: Tutumo, Mawayana, Xerew and Katwena (Yde 1965: 319, map).

As the route of these voyages of reconnaissance generally went from north to south, with travellers setting out from Guiana and not Brazil, the information we have refers only to the indians in the border region. As they were more easily accessible to these disease-bearing expeditions, as well because of the trade links with the Taruma and Wapixana, around 1890 the Waiwai suffered a demographic collapse as a result of the spread of previously unknown diseases. This led to an increase in inter-tribal marriages. Previously there had been frequent marriages between the Waiwai and other peoples, but later, at the turn of the century, the Waiwai intensified this process with the Parukoto indians, mainly the Xerew and the Mawayana, to the south and with the Taruma, to the north (Fock 1963: 267).

In the 20th century

By the beginning of the 20th century the Waiwai were divided between two areas: to the north, on the Acaraí range, and to the east, on the upper Mapuera. The first decade of the century was marked by inter-tribal conflicts which emphasized the separation of the two sub-groups and, at the same time, led to a marked population decline. The conflicts took place between the Waiwai and the Parukoto. By December 1913, when Farabee visited the Waiwai, the wars had ended and the former Parukoto enemies had been integrated into the Waiwai, with the former however making up the greater number (cf. Howard 2001: 234-235).

In 1919, 1922 and 1923 the Jesuit missionary Father Cuthbert Cary-Elwes S.J. visited the Waiwai and also referred to the importance of their trading activities with the Taruma and the Wapixana (cf. Colson and Morton 1982). The Waiwai and the Parukoto, from the north and east, continued to inhabit the mountain region, although the northern group had started to also occupy the upper Essequibo in British Guiana, where they were mentioned by Walter E. Roth in early 1925. Before Roth could set out to meet the Waiwai, as he had planned, the Waiwai went to meet him, as news had spread of a traveller in the region carrying goods such as salt, fish hooks and axes. Trading relations with the Taruma had ceased since, according to Roth, the Taruma in this area were practically extinct and the survivors integrated into the Waiwai (Roth 1929: IX, X).

From approximately 1925 to 1950 a migratory movement of Waiwai towards the upper Essequibo took place. They abandoned the region of the mountains and headwaters in order to live on the banks of larger rivers. The British-Brazilian border commission confirmed this movement in 1935: the majority of the Waiwai were on the Essequibo in British Guiana, whilst the Mapuera was inhabited by other Parukoto groups (Xerew, Mawayana etc.), together with a few Waiwai. In effect the Waiwai and Parukoto shared a language and similar ways of life. The Parukoto, originally from the middle Mapuera, had for example introduced the Waiwai to the use of canoes, typical of Amazonian groups. (Fock 1963: 8-9).

Up to 1950 the situation of the Waiwai did not undergo any significant change, except as regards their territory, as was confirmed by several visitors participating in ethnographic or official missions: in 1938 the Terry-Holden expedition of the American Museum of Natural History (see Aguiar 1942); and in 1947, the Peberdy mission on behalf of the government of British Guiana (Peberdy 1948).

Missionary presence

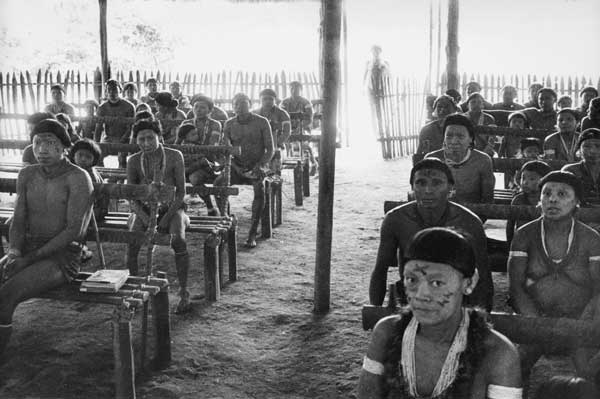

A large scale transformation of the lives of the Waiwai began in early 1950 with the arrival of a ‘missionary front’ on the upper Essequibo: the Unenvangelized Fields Mission (UFM) began attracting to British Guiana the greater part of the Mapuera and Nhamundá populations. The evangelical reporter Homer E. Dowdy tells in his book Christ’s Witchdoctor: From Savage Sorcerer to Jungle Missionary that at the start of this enterprise were the missionaries Neill, Rader and Robert Hawkins, three brothers from Texas whose aim was to establish themselves in indigenous regions not yet evangelized in order, in the name of the mission, to save their souls to Christ by bringing them the Gospel. Prior to making contact with the Waiwai, the two elder brothers, Neill e Rader, had spent ten years among the Macuxi on the banks of the Rio Branco in Brazil.

When in 1948 they decided to contact the Waiwai, the Hawkins could not get authorization from he Brazilian government and therefore decided to travel to British Guiana, where they were also at first refused authorization (Dowdy 1963: 33). It was only the following year, in January 1949, when the government agent responsible was transferred that his successor authorized them to visit the Waiwai on the Essequibo.

The ‘Mission among the Waiwai’ was founded by several missionaries. In 1949 few Waiwai were living on the British side. However in the border region on the Brazilian side the indigenous population was substantial. From the start the interests of the missionaries lay in making incursions into Brazilian territory, by descending the Mapuera and continuing as far as the Nhamundá, and attracting the several hundred indians to the mission inside the territory of the then British colony (Frikel 1970: 29-30). In order to attract the indians the missionaries despatched indigenous messengers to offer sought-after items such as fish hooks, mirrors, knives and beads, as well as to spread the message that ‘the world will end in an enormous conflagration and the mission could show them the way to salvation in a better life’ (Almeida 1981). In the face of these attractions the population of the area increased from 80 people to more than 250 in just three years, forming a conglomeration of groups including the Waiwai, Mouyennas (Mawayena), Xerew, Piskaryenna and Hixkaryana (Yde 1960: 83, and 1965: 1 and 9). This rapid concentration resulted in the formation of a single settlement: Kanashen or Konashenay, a village artificially created by the Mission and whose name embodies the idea that ‘God loves you here’ as a way of enticing the indians to move to live there.

A series of reports and versions abound concerning the so-called ‘conversion’ of the Waiwai. A paradigmatic example is the trajectory of Ewka, a shaman and charismatic leader who became an important reference for both indians and non-indians, as is shown by ethnographic experiences and sources dating from different periods. According to Dowdy, who gives Ewka (and his book) the title of Christ’s Witchdoctor, this was a case of a savage shaman who became a jungle missionary, changing the history of the Waiwai who, together with their leader, exchanged the fear of the kworokyam spirits for faith in Christ.

Dowdy relates the earliest contacts between Ewka and the kworokyam (“the centre of Waiwai spiritual life” – 1963: 23) who appeared to the young shaman in a dream about wild pigs. Under the guidance of the spirit(s) of the wild pig, Ewka was initiated into shamanistic learning and entered into a pact to not eat the meat of this animal in exchange for its wide-ranging help, for example with healing and hunting. When the missionaries arrived Ewka offered to teach them the Waiwai language. During the long hours of language teaching he heard descriptions of the God of the missionaries and his son Jesus. To the eyes of the missionaries, studying the habits and ways of the Waiwai, including their language, in order to catechize them and bring them to the path of God (which they translated as ‘Kaan yesamarî’), the importance to the Waiwai of the exchange of the ekatî (soul) and in particular of the yekatî yewru (the eye of the soul) did not go un-noticed. For this reason they translated the Holy Ghost as ‘Kiriwan Yekatî’, in other words the ‘Good Spirit’ of God. They preached that the indians needed to be in a constant state of exchange with this in order not be punished in Purgatory, but rather to ascend to Heaven. The missionaries felt that, by means of valuable gifts such as outboard motors and red shorts, they could win Ewka over, especially if he could be made to see that Jesus was the good spirit, infinitely greater than the evil spirits represented according to the missionaries by the kworokyam and which they translated as the Devil. On this basis the missionaries proposed to Ewka that he not only kill a wild pig, but that he eat its meat, thereby proving to himself and the others that the spirits had no hold over a person protected by God. This was done and led, according to Dowdy, to the conversion first of Ewka and then of his followers. By 1956 hardly a week went by without a public confession of a new faith in Christ during the weekly meetings and acts of worship instituted in Kanashen every Wednesday, Friday and Sunday.

The relations that the Waiwai developed with the missionaries occurred on various levels and for this reason the process should not be referred to simply as a ‘conversion’ to Christianity, but rather seen within the context of a complex network of relations with external powers important for the acquisition of their own culture. We need to bear in mind that, starting with the earliest travellers, reports refer to the particular interest of the Waiwai in promoting relations with outside groups and to the existence of an extensive trading network involving other groups in the region such as the Wapixana, Tiriyó, Mawayana and Xerew, amongst many others. This was the context in which their special interest in establishing relations with the missionaries occurred, together with their enthusiasm for accepting the missionary proposal to act as indigenous messengers and contact other indigenous groups such as the Xerew of the lower Mapuera in 1954, the Mawayana of the upper Mapuera in 1955-56, the Tiriyó and Wayana in Suriname in 1957, the Kaxuyana of the Cachorro river and the Hixkaryana of the Nhamundá river in 1957-58, two Yanomami groups (Xirixana and Waika) in 1958-59 and 1960-62, various groups in the Tumucumaque area (such as the Tunayana, Wajãpi, Wayana and Kaxuyana) in 1963-65, the Katwena and Cikyana of the Trombetas in 1966-67 and the Waimiri-Atroari of the Alalaú river in 1969-70 (cf. Howard 2001: 285-286). This is something they had been doing before contact with the missionaries and which, after contact, they could undertake with special support, given the material and immaterial tools provided by the mission.

In 1971 the Kanashen mission was expelled by the socialist-leaning government of the newly-independent Guyana. The indians dispersed; only a few families remained in the area. A small part migrated to the Ararparu mission in Suriname, whilst the greater part returned to Brazil. In the same year the indigenous leaders and pastors Kiripaka and Yakuta, the latter the brother of Ewka, organized the move by fifteen families to the Anauá river in the state of Roraima. In 1974 under the leadership of Ewka the remainder returned to the Mapuera, their place of origin. The missionaries expelled from Guyana spilt up and followed the migration of the indians to the Brazilian side. Some went to the Waiwai in Roraima and joined the MEVA missionary organization. In 1976 others set up on the Mapuera as part of the MICEB (Missão Cristã Evangélica do Brasil). During this time contact expeditions in search of other indigenous groups continued to be organized and new places of settlement were founded, as was the case of the expedition in search of the Karapawyana of the Jatapu river in 1974-1980, leading four years later to the founding of the new Waiwai community of Jatapuzinho, a tributary.

Current relations with non-indians

The interest of the Waiwai in establishing relations with different Others is not confined to the indigenous world [see the article History of contact], nor to the non-indigenous world (to which they have been opening up to increasing contact over the last fifty years), nor even to the world of humans [see the article Rituals and transformations]. As regards their current relations with non-indians, these include missionaries (mainly evangelical, but also catholic missionaries at Anauá in the TI Wai Wai), representatives of government agencies (Funai, Funasa and the Ministry of Education), politicians and local authorities, riverbank populations, traders, researchers, ranchers, loggers and squatters. Included amongst these are some that can be judged to represent threats and pressures.

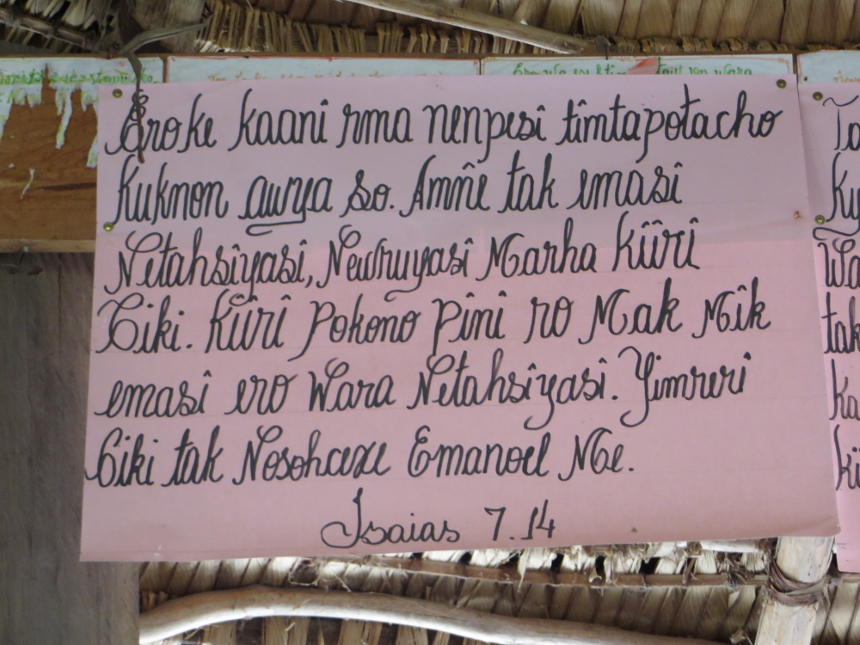

Following their arrival amongst the Waiwai in the 1950s the missionaries introduced literacy teaching as the means to achieve their catechizing aims. They saw this as the best way to disseminate the Bible, which they have translated in its entirety (Old and New Testaments). It was published in 2001 by the Unevangelized Fields Mission (UFM) in collaboration with the Missão Evangélica da Amazônia (MEVA) under the title ‘Kaan Karitan – The Holy Bible in the Uaiuai language’. Its gilded type shines out from the hard black cover of its more than 600 pages (in an initial print run of 4,000 copies).

Without doubt the introduction of the written language was a powerful tool for introducing the Gospel, but is it the case that this means the Waiwai are effectively abandoning traditions of oral transmission of their knowledge, practices and cosmological views? We should bear in mind that it is the Waiwai, along with other indigenous peoples, who are in fact demanding access to literacy training and formal education as a basic condition of their autonomy. This channel of communication enables the Waiwai to reproduce their culture in a format accessible to non-indians: the drafting of projects and other documents where they themselves are the authors.

The experiences of the different Waiwai communities in the three Terras Indígenas varies considerably as regards the existence (or not) of schools in the communities and the professional status of their teachers. In Pará for example the Nucleo de Educação Escolar Indígena has been working since 1997 with the teachers of the village of Mapuera, where sixty percent of the population is of school age. In Roraima this process is more recent, but discussions and collaboration are now taking place between the Waiwai and the CIR (Conselho Indígena de Roraima), and organizations such as OPIR (Organização dos Professores Indígenas de Roraima) and those of Waiwai women, such as OMIR (Organização das Mulheres Indígenas de Roraima).

In respect of Funai and Funasa staff, the experience also varies. In Pará for example, there is a Waiwai who works for Funai with a certain level of stability, whilst transfers of chiefs of post in Roraima are frequent. The majority of health programmes are linked to the joint activities of Funasa and NGOs. Thus in Roraima the CIR operates together with Funasa in the area of health. They jointly organize courses and specialist training for Waiwai health workers in Jatapuzinho and on the Anauá. These are paid salaries to look after the monthly deliveries of medicines and to collect malaria examination slides.

There are a number of programmes and projects carried out among the Waiwai. In addition to the training programmes for indigenous health workers and teachers, there are projects for the collection of forest products (brazil nuts, for example), fish and animal breeding (including cattle), processing and management of products for income generation (handicrafts, for example), territorial monitoring and protection (in some cases in collaboration with other indigenous groups, for example the Waimiri-Atroari) and other activities.

There are also those projects with undesirable impacts, such as the planned Cachoeira Porteira, Carona and Nhamundá hydroelectric plants, as well as the plant already built on the Jatapu at the end of the 1980s and which brought problems for the Waiwai. To mitigate the impacts of this project the government provided the Waiwai of Jatapuzinho with an electricity generator and a monthly allowance of diesel fuel which they collect from the hydroelectric plant. In addition, the municipality of Caroebe also supplies a monthly quota of gasoline (150 to 200 litres) to the community. In Jatapuzinho there are also some elderly indians who receive the basic pension under the federal social security system

Socio-environmental practices and economic activities

The Waiwai annual cycle alternates between the dry season and the rainy season. In the former, food is plentiful and collective life intense. The latter is however characterized by scarcer resources, forcing Waiwai families to disperse to their more isolated swidden gardens.

As a consequence of this cycle, but also of the problems arising with large population densities, gardens are of two types: those situated near to the village and those at a distance. Many families spend a large part of the rainy season at the latter. They also make use of these when resources near to the village are insufficient for to meet needs.

The gardens are prepared (cleared, felled, burned and tidied) from August to September, when the rains cease. Planting occurs between January and March and is a collective task. The main species grown are cotton, pineapple, different varieties of banana, sugarcane, papaya, root vegetables such as yams and different types of potatoes and, above all, bitter manioc. From this, once the toxin is extracted, they make beiju [unleavened bread], farinha [manioc flour] and tapioca [starch] drinks.

As well as slash-and-burn agriculture, subsistence activities are based around hunting, fishing and gathering wild products. The main animals hunted are tapir, deer, wild pig, monkey (spider, howler and capuchin), curassow, trumpeter, agouti, cavy, armadillo, turtle, toucan, macaw etc. Birds are also hunted for their plumage and the feathers used in handicrafts. Since the 1950s Waiwai men have been hunting with shotguns. However when they have no ammunition they continue to use bow and arrow; these are also used for fishing. The fish most commonly caught are: giant trahira, catfish, pacu, piranha, etc. Gathering represents an important dietary supplement in which the following are important: wild cashew, assai, burity, peach palm and nuts, above all brazil nuts. Brazil nuts are collected mainly for sale, as is the case with manioc flour, canoes and handicrafts. The items most commonly purchased with the money from the sale of these products are outboard motors, clothes, fish hooks, fishing line, ammunition, soap, salt and manufactured hammocks.

Handicraft production has increased considerably, especially when the Waiwai wish to acquire manufactured goods. Women make pottery, manioc graters, loincloths, and seed necklaces, amongst other items. The men make baskets, combs, feather adornments, bows and arrows. The greater part of the handicraft production is taken to be sold in Boa Vista, and also in Manaus. In recent years some younger Waiwai have sold handicrafts at the Festa do Boi in Parintins. The Waiwai, especially the younger generation, also earn money or goods by working in riverbank settlements such as Entre Rios or Caroebe.

Kinship and socio-political organization

Waiwai kinship is closely connected to the socio-political organization. This is based on complementarities between the sexes, cooperation among neighbours, the obligations of a son-in-law to his father-in-law, and the acknowledgement of some men as particularly influential.

Clans, lineages, halves, social classes or distinction by economic wealth do not exist. Consanguinity and affinity are defined bilaterally and kinship terminology is based on several criteria including: gender and generational relations, cross versus parallel relations and the relative ages of siblings. From the perspective of an individual adult the following distinctions are made: epeka komo (neighbours comprising siblings and their families), woxin komo (families of one’s spouse’s kin, who constitute affines) and tooto makî (people with whom the subject has no relationship).

Young people generally marry between the ages of 16 and 24. The ideal match is considered to be one between real and classificatory cross cousins. The son-in-law takes on a series of duties in relation to his father-in-law: to live nearby, build a house, plant a swidden garden, share food obtained by hunting and fishing. The son-in-law gains his independence only slowly, or when he himself becomes a father-in-law able to demand the same duties. Leaders try to keep both sons and sons-in-law living close to them. Leaders need wives and, should his wife die, the leader is expected to re-marry or to relinquish the role of leader.

Prior to the arrival of the missionaries it was common for the Waiwai to have several husbands or wives during their lifetimes. Usually this involved serial monogamy, although polygamy and polyandry sometimes occurred, although usually only temporarily. Under the influence of the missionaries new institutions were imposed: pre-nuptial celibacy, long term monogamy and the absence of divorce.

Each ‘Waiwai community’ constitutes a unit of political organization. There is no ‘ethnic’, ‘tribal’ or regional organization, despite the fact that relations between the different ‘Waiwai communities’ are complex and important and the fact that associations have been created (for example, AITA TROMA in Mapuera) as a response to new demands arising from the equally complex contact with non-indians.

It would be difficult to envisage a leader of a community who didn’t have a certain level of persuasive skills, since these are needed in order to mobilize followers willing to build a new village, prepare new gardens and undertake the necessary preparations for festivities. Nowadays, following their permanent contact with both other indians of the region and non-indians, the Waiwai term kayaritomo formerly used to designate the leader of a village has been replaced by the regional term tuxawa. It is the tuxawa who is responsible for coordinating relations with non-indians and internally. He does this by nominating work leaders (antomañe komo) and pastors (Kaan mîn yenîñe komo) who together are known as enîñe komo, those who watch over and care for the community.

Social control is never exercised by physical force, but rather by persuasion, the pressure of public opinion and, to a large extent, by gossip. All disagreements are mediated by sophisticated negotiation tools, exemplified by the ritual dialogue known as Oho (which so impressed researchers such as Fock in the 1950s) and by other indirect methods. Fear of witchcraft has always served as a means of control; nowadays the pastors threaten the punishment of God in cases of conduct considered inappropriate. In serious cases a council made up of leaders (tuxawas, work leaders and pastors) hold long sessions with all those involved, in search of a solution. Some disputes may be publicly discussed in the church or the umana, the large ceremonial house where festivities are also celebrated together.a

Rituals and transformations

Prior to the arrival of the missionaries, the two great communal festivities among the Waiwai were the shodewika festivities (where one village would visit another) and the yamo rituals (when fertility spirits invoked by masked dancers would come to live in the village for several months). At these festivities there would always be large quantities of fermented drinks, dancing and games. Following several years of missionary presence and insistence, the Waiwai gradually agreed to exchange fermented drinks for drinks made of the burity palm. This was one of the changes introduced by the charismatic leader Ewka during the time when they lived on the upper Essequibo in Guyana.

Nowadays they continue to celebrate two great festivities which, thanks to the missionaries, have come to be called Kresmus (the Waiwai pronunciation of the English word Christmas) celebrated at the end of the year and, in April, the Festa de Páscoa [Easter Festival], when baptisms commonly take place. As their names and dates suggest, these festivities incorporate certain Christian references, although it is worth noting that the Christmas festival falls exactly in the dry season and the Easter festival coincides with the end of this season and that these are the times when ritual festivities were held prior to the arrival of the missionaries. It is also questionable whether the various actors involved in evangelization really managed to replace Waiwai cosmological views and philosophies. Everything suggests that the logic of substitution does not make sense, but rather the logic of transformation and selection.

One relevant transformation concerns the role of guests at these festivities. This is no longer the case of inhabitants of different villages who visit each other, but of Waiwai hunters returning to their own village after a long hunting trip to obtain food for the festivity. This return is ritually celebrated by two arrivals or entrances. In the first, the hunters appear as ‘visitors’ appropriately adorned with feathers of large and small hawks (yaimo and wikoko) and carrying all the fresh meat on their bodies to the large ceremonial house known as the umana. Here they shoot arrows at animals, mainly birds, made of wood and hung from the roof of the umana for this purpose.

After returning to their canoes the hunters/guests ritually enact a second arrival/entry to the umana playing flutes and now carrying smoked meats in large awci (a type of backpack made of banana leaves). In the umana the hosts, who in this role are called the lords of the juice (yîmîtîn), offer burity juice (you yukun) and beiju to the hunters/guests, receiving in exchange the fresh and smoked meats to be prepared for collective consumption.

During the whole period of the festivities the meals are communal and various acts of worship are organized that involve the singing of hymns, many composed especially for the festival. There are also dancing and a large number of games and jokes, amongst which both old indigenous activities (for example, dances of the animals) and newer activities resulting form contact with indians (for example, football).

Each in their own manner, these dances, games and jokes make up rituals by which the Waiwai accommodate outside forces and resources. This can include, for example: their relations with animals and their powers (in accordance with the different cosmological qualities of these) by means of the dances of the animals; celestial powers by means of feather work; spiritual powers (indigenous and Christian) by means of music and invocations; and, amongst other things, their relations with other indians and with non-indians by means of the ritual for visitors known as pawana.

Shamanism

Currently there is no Waiwai calling himself a shaman. However since shamanism cannot be defined in a reductionist way as the presence of shamans, this does not mean that shamanistic ways of thinking and behaving are no longer present. These manifest themselves, for example, in the form of accusations of sorcery, almost always attributed to Waiwai from other communities or indians from other places. In this way no death is ever considered as a natural event, but is always connected to events of another order. This is similarly the case with the varied experiences and conceptions of dreams. Here is not the place to go deeper into these realms that are confined to closed circles. In this context the Waiwai say that such things are hidden, nobody speaks of them, but everyone knows and that from such acts of sorcery there is no going back, things have to take their course.

Notes on sources

Sources of information on the Waiwai can be divided into several groups: works or reports of historians, travellers or missionaries; linguistic texts; books, theses and articles; and documents and reports of Funai, Funasa and the Ministry of Education. It should be borne in mind that, following the establishment of the mission among the Waiwai, the missionaries took on the role of mediators and translators for a number of researchers and travellers undertaking field work or travel, particular during the stirring 1950s. Amongst the visitors were the archaeologists Betty Meggers and Charles Evans (cf. Evans and Meggers 1955, 1960, 1964, 1979, Meggers 1971), the British botanist Nicholas Guppy (1954, 1958), the Polish traveller Arkady Fiedler (1968) and the Danish anthropologists Niels Fock and Jens Yde taking part in the first ethnographic expedition of the National Museum of Denmark in 1954-55 and the second in 1958. These expeditions resulted in the publication of an important monograph on Waiwai religion and society (Fock 1963) and a wide ranging study of Waiwai material culture (Yde 1965).

There are multiple sources of information on the Waiwai at the end of the 20th and the beginning of the 21st centuries. Some of these will be of long term importance, as is the case of some of the missionary and anthropological sources. Amongst these are: George Mentore, who wrote his doctorate at the University of Sussex on the political economy of the Waiwai village of Shepariymo based on his field work among the Waiwai of Guyana (cf. Mentore 1983-84, 1984, 1987, 1993, 2005); Peter Roe and Peter Siegel who also carried out field work in Shepariymo in 1985 (cf. Roe 1989, 1990 and Siegel 1985, 1987); Catherine Howard who undertook field work from April 1984 to November 1986 in Kaxmi (Roraima) for her doctorate at the University of Chicago on contact expeditions (cf. Howard 1986, 1991, 1993, 1994, 2001); Ruben Caixeta de Queiroz who carried out field work during the first two months of 1991 and the last five months of 1994 on the Mapuera (Pará) for his doctorate at the Université de Paris I et Paris X on the intercultural encounter ‘en anthropologie filmique’, making a number of ethnographic films and serving as the anthropology coordinator for the official identification of the Terra Indígena Trombetas/Mapuera and its limits (cf. Caixeta de Queiroz 1999, 2004); Jorge Manuel Costa e Souza who carried out fieldwork in 1997 on the Jatapuzinho for his masters degree at the Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina on the relationship between the Waiwai and ‘modernity’ (cf. Costa e Souza 1998); Stephanie Weparu Aleman who carried out three to five months field work a year from 1997-2002 for her doctorate at the University of Wisconsin (Aleman 2006); and from the Núcleo de História Indígena e do Indigenismo at the Universidade de São Paulo (NHII/USP), the researchers Carlos Machado Dias Junior who undertook field work from 1997 to 1999 and again from September 2003 to June 2004 in different Waiwai communities in Roraima, Pará and Amazonas (cf. Dias Junior 2000, 2006), as well as my field work carried out, so far, from December 2001 to April 2002 and from December 2002 to January 2003 on the Jatapuzinho (cf. Schuler Zea 2006)

Sources of information

- AGUIAR, Braz Dias de. Trabalhos de comissão brasileira demarcadora de limites – primeira divisão – nas fronteiras de Venezuela e Guianas Britânica e Neerlandesa, 1930-1934. In: Annais do IX Congresso Brasileiro de Geografia, vol. 2. Rio de Janeiro: Conselho Nacional de Geografia.

- ALMEIDA, Maria da Penha de. Relatório de eleição e delimitação das áreas dos Pls Nhamundá e Mapuera (divisa dos Estados do Amazonas e Pará). Brasília : Processo FUNAI 2989/80, 1981.

- BOS, G. “Atorai, Trio, Tunayana, and Waiwai in Early Eighteenth Century Records”. Folk: 5-15, 1985.

- BROWN, Charles Barrington. Camp and Canoe life in British Guiana. London, 1876.

- BROWN, Charles Barrington, e William Lidstone. Fifteen thousand miles on the Amazon and its tributaries with map and wood engravings. London : Stanford, 1878.

- CAIXETA DE QUEIROZ, Ruben. Les Waiwai du Nord de L’amazonie (Brésil) et la rencontre interculturelle: Un Essay d’anthropologie filmique. Paris-Naterra : Université de Paris X, 1998. Tese de doutoramento.

- -------. “A saga de Ewka: Epidemias e evangelização entre os Waiwai”. In: Robert Wright (ed.): Transformando os deuses. Os múltiplos sentidos da conversão entre os povos indígenas no Brasil. Campinas : Editora da Unicamp, 1999.

- -------. Relatório de Identificação e Delimitação: Terra Indígena Trombetas/Mapuera. Brasília : Funai, 2004.

- COLSON, Audrey Butt. “Waiwai: religion and society of an amazonian tribe american (Book review)”. Anthropologist 66: 683-684, 1964.

- -------. “Material culture of the Waiwai (Book review)”. Man 1: 271, 1966.

- ------- & John Morton. “Early missionary work among the Taruma and Waiwai of Southem Guiana – the visits of Fr. Cuthbert Cary-Elwes, S. J. In 1919, 1922 and 1923”. Folk 24: 203-261, 1982.

- COSTA E SOUZA, Jorge Manoel. Os Waiwai de Jatapuzinho. Um irresistível apelo à modernidade. Florianópolis : Dissertação de Mestrado, Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina, 1999.

- COUDREAU, Henry. La France Équinoxiale, vols 1-2 (vol. I: Études sur les Guyanes et l’Amazonie; vol 2: Voyages à travers les Guyanes et l’Amazonie). Paris.

- -------. Voyage au Yamunda (21 janvier 1899 – 27 juin 1899). Paris, A.Lahure, 1899.

- COUDREAU, Olga. Voyage au Trombetas (7 août 1899 – 25 novembre 1899). Paris, A. Lahure, 1900.

- -------. Voyage à la Mapuera (21 avril 1901 – 24 decemvre 1901). Paris, A. Lahure, 1903.

- DIAS JR., Carlos Machado. Próximos e distantes. Estudo de um processo de descentralização e (re)construção de relações sociais na região sudeste da Guiana. São Paulo: Dissertação de Mestrado, USP, 2000.

- -------. Entrelinhas de uma rede. Entre linhas Waiwai. São Paulo: Tese de Doutorado, USP, 2006.

- DERBYSHIRE, Desmond. Textos hixkaryana. Publicações avulsas do Museu Paraense Emilio Goeldi no. 3. Belém: Museu Paraense Emilio Goeldi. 1965.

- -------. Discourse redundancy in Hixkaryana. International journal of american linguistics 43: 176-1 88, 1977.

- -------. Another kind of “Hearsay Particle” in Hixkaryana (Brazil). Notes on Translation 70: 8-13. 1978.

- -------. A diachronic explanation for the origin of OVS in some Carib languages. Work papers of the Summer Institute of Linguistics 3:35-46. University of North Dakota Session : Summer Institute of Linguistics, 1979.

- DOWDY, Homer. Christ’s witchdoctor. London : Hodder & Soughton, 1963.

- -------. Christ’s jungle. Oregon : Vision House, 1995.

- EVANS, Clifford e MEGGERS, Betty. “Life among the Waiwai Indians.” In : National geographic magazine 107, 1955.

- -------. “Archaelogical investigations in British Guiana”. In : Bureau of american ethnology bulletin 177. Washington. D.C. : Smithsonian Institution.

- FARABEE, William Curtis & University of Pennsylvania University Museum. The Central Karibs. Oosterhout : Anthropological publications, 1967.

- FIEDLER, Arkady. Bei Arawak und Waiwai. Ich lebte unter den Indianern Guayanas. Leipzig : Brockhaus, 1968.

- FOCK. Niels. Waiwai religion and society of an Amazonian tribe. Copenhagen : National Museum, 1963.

- -------. Authority – its magico-religious, political and legal agencies – among caribs in northern south america. Sonderdruck aus den Verhandlungen des XXXVIII. Internationalen Amerikanistenkongresses. Stuttgart-München: 12. bis 18. August, 1968.

- FREITAS, C.P de. On the frontier of british Guiana and Brazil. Timehri 26: 123-145, 1944.

- FRIKEL, Protasio. Zur Linguistisch-Etnologischen Gliederung der Indianerstämme Von Nord-Pará (Brasilien) Und Den Anliegenden Gebieten. Anthropos (Freiburg) 52: 509-631, 1957.

- -------. Os Kaxuyana: notas etnohistóricas. Belém : Museu Paraense Emilio Goeldi (Publicações Avulsas 14), 1970.

- GUPPY, Nicholas. Wai-Wai. Through the forests north of the Amazon. Harmondsworth : Penguin Books, 1961.

- HARCOURT, Robert. A relation of a voyage to Guiana – 1603. London, The Hayklet Society, 1928. 203 p.

- HAWKINS, Neill W. A Fonologia da Língua Uaiuai. Boletim etnografia e tupiguarani: 1-49. 1952.

- -------. A Morfologia do Substantivo na Língua Uaiuai. Publicações avulsas do Museu Nacional, 1962.

- HAWKINS, Robert E. The winning of a Waiwai witchdoctor: from fear to faith. Dallas : Bible Fellowships, Inc., 1956.

- -------. Aprendendo a Falar Uaiuai. Boa Vista : MEVA (Missão Evangélica da Amazônia), 1976.

- -------. Waiwai Translation. The Bible Translator : 164-171. 1962.

- -------. Dicionário Uaiuai-Português. Boa Vista : MEVA (Missão Evangélica da Amazônia), 2001.

- -------. Gramática da Língua Uaiuai : MEVA (Missão Evangélica da Amazônia), s/d.

- HOWARD, Catherine Vaughan. “A domesticação das mercadorias : estratégias Waiwai”. In: ALBERT, Bruce; RAMOS, Alcida Rita (Orgs.). Pacificando o branco : cosmologias do contato no Norte-Amazônico. São Paulo : Unesp, 2002. p. 25-60.

- --------. “Pawana : a farsa dos visitantes entre os Waiwai da Amazônia”. In: VIVEIROS DE CASTRO, Eduardo; CUNHA, Manuela Carneiro da (Orgs.). Amazônia : etnologia e história indígena. São Paulo : USP-NHII ; Fapesp, 1993.

- --------. Wrought identities : the Waiwai expeditions in search of the "unseen tribes" of Northern Amazonia. Chicago : Univers. of Chicago, 2001. (Tese de Doutorado)

- -------. "Fragments of the Heavens: Feathers as Ornaments among the Waiwai. In : Ruben E. Reina and Kenneth M. Kensinger (ed.). The Gift of Birds. Philadelphia : University Museum, University of Pennsylvania, 1991.

- MENTORE, George P. Wai-Wai Labour Relations in the Production of Cassava. Antropologica (Caracas) 59-62: 199-221. 1983-84.

- -------. Shepariymo. The political economy of a Waiwai village. [Ph.D. dissertation, University of Sussex]. 1984.

- -------. Waiwai Women. The Basis of Wealth and Power. Man 22: 511-527, 1987.

- -------. Tempering the Social Self: Body Adornment, Vital Substance, and Knowledge among the Waiwai. Journal of Archeology and Anthropology 9: 22-23. 1993.

- -------. Of Passionate Curves and Desirable Cadences. Themes on Waiwai Social Being. Lincoln and London : University of Nebraska Press, 1995.

- MIGLIAZZA, Ernest C. Grupos lingüísticos do Território Federal de Roraima. Actas do simpósio sobre a biota amazônica (antropologia) (Belém) 2: 153-1 73, 1967.

- -------. “Languages of the Orinoco-Amazon basin current states”. In : Klein, H. E. M und L. R. Stark (eds.). South american indian languages : retrospect and prospect. Austin : University of Texas Press, 1985.

- MORTON, John: Women as Values, signs and power: aspects of the politics of ritual among the Waiwai. Antropologica (Caracas) 59-62: 223-261. 1983-84.

- OGILVIE, John. Creation Myths of the Wapisiana and Taruma, British Guiana. Folklore (London) 5: 64-72. 1940.

- PEBERDY, P.S. Report of a survey on amerindian affairs in the remote interior. Colonial Development and Welfare British Guiana, 1948.

- ROE, Peter Of Rainbow Dragons and the Origins of Designs. The Waiwai Uruperi and the Shipibo Ronin Ehua. Latin American Indian Literatures Journal 5: 1-67. 1989.

- -------. “The language of the plumes: “Implicit mythology” in Shipibo, Cashinahua and Waiwai feather adornments. In: Mary H. Preuss (ed.): Selected papers from the VLL International Symposium On Latin American Indian Literatures. Culver City, Calif.: Labyrinthos (105- 135), 1990.

- ROTH, Walter E. An introductory study of the arts, craft, and customs of the Guiana indians. Smithsonian Institution, 1924.

- -------. Additional studies of the arts, craft, and customs of the Guiana indians, with special reference to those of southern british Guiana. Smithsonian Institution, 1929.

- -------. “Trade and barter among the Guiana indians”. In: Lyons, Patricia J. (ed.). Native South Americans. Boston : Little, Brown & Co., 1974.

- SALZANO, Francisco Mauro et al. The Wai Wai indians of South America: history and genetic. Annals of Human Biology, Londres : s.ed., v. 23, n. 3, p. 189-201, 1996.

- SCHOMBURGK, Richard. Reisen in Britisch-Guiana in Den Jahren 1840-44 Nebst Einer Fauna Und Flora Guiana's Nach Vorlagen Von Johannes Müller, Ehrenberg, Erichson, Klotzsch, Troschel, Cabanis Und Andern. Leipzig: J. J. Weber. 1847.

- -------. “Report of the third expedition into the interior of Guayana, comprising the journey to the sources of the Essequibo to Fort San Joaquim, on the Rio Branco”. Journal of the Royal Geographical Society of London 10 (part 2: 159-267), 1840-41.

- SIEGEL, Peter. Ethnoarchaeological study of a Waiwai village in the Tropical Forest of Southern Guyana. Paper presented at the XI Congreso Internacional de Arqueologia del Caribe, San Juan, Puerto Rico, 1985.

- -------. Small village demographic and architectural organization: an example from the Tropical Lowlands. Paper presented at 52"d Annual Meeting of the Society for American Archaeology, Toronto, 1987.

- UFM (Unenvangelized Field Mission) Kaan karitan: A Bíblia Sagrada na língua Uaiuai. Pennsylvania : UFM International (e Boa Vista: MEVA), 2001.

- VITORINO, Marinalva M. Dicionário bilíngüe Wai-Wai/Português, Português/Wai-Wai. Boa Vista : Missão Evangélica da Amazônia, 1991. 41 p.

- YDE, Jens. Material culture of the Waiwái. Copenhagen : National Museum of Denmark (Ethnographic Series, 10), 1965.