Puyanawa

- Self-denomination

- Where they are How many

- Linguistic family

Like many peoples of Acre, the Puyanawa suffered heavily from the boom in rubber and caucho extraction in the region at the start of the 20th century. Since the first contacts with non-Indians, many have died in direct confrontations or from diseases contracted during the colonization process. The survivors were forced to work in the rubber extraction areas – the seringais – and quickly found their way of life decimated due to the methods used by the ‘rubber barons’ to keep the Indians working under their yoke. The Puyanawa were expelled from the lands, missionized and education in schools that banned any expression of any trace of their culture.

It was only with the beginning of the process of demarcating their territory that Puyanawa culture was once again valued by the Indians themselves, who have worked hard to recuperate their native language, a difficulty task given the small number of speakers left.

Language

The Puyanawa language belongs to the Pano linguistic family.

The first person among the Puyanawa to realize the need to maintain the group’s language was Railda Manaitá, who, even without outside support or pedagogical material tried to persuade the rest of the population of this need through language lessons. For the lessons she created an alphabet based on Portuguese and compiled a list of words and phrases in Puyanawa.

The Puyanawa language is called Ûdikuî by its speakers, ‘true language.’ The number of active speakers at the time of the field survey (July 1990) was twelve among a total population of 385. It should be noted that the children, those who could perpetuate the language, are monolingual in Portuguese, which is leading to a process of linguistic obsolescence and the potential extinction of this invaluable cultural heritage.

[Aldir Santos de Paula, 1992]

Threatened language

The Puyanawa language began to disappear around 1910 when the Indians were abducted and enslaved at the orders of Colonel Mâncio Agostinho Rodrigues Lima to work in rubber extraction and perform other services on his farm estate. The first measure taken by the rubber bosses was to prohibit use of the indigenous language and create a school for everyone to learn Portuguese. Anyone speaking Puyanawa was heavily punished.

Over the last few decades, almost all the speakers of the language have died, people who were children at the time of contact. After being enslaved, the Indians grew ashamed of their language, which was almost forgotten.

In 2009, only three of the approximately 500 Puyanawa Indians spoke Puyanawa: Railda Manaitá, 79, the only person fluent in the language; her brother, Luiz Manaitá, 85; and the former village leader Mario Puyanawa, 65.

Despite the efforts to revive the language, the results are still limited: none of the students is able to maintain a dialogue in Puyanawa.

[Luiza Bandeira/Folha de São Paulo, 2009]

Further reading

See the reports on threatened indigenous languages in Brazil:

Língua proibida revive no Acre (Folha Online) Os três últimos falantes da língua poianaua (Folha Online)

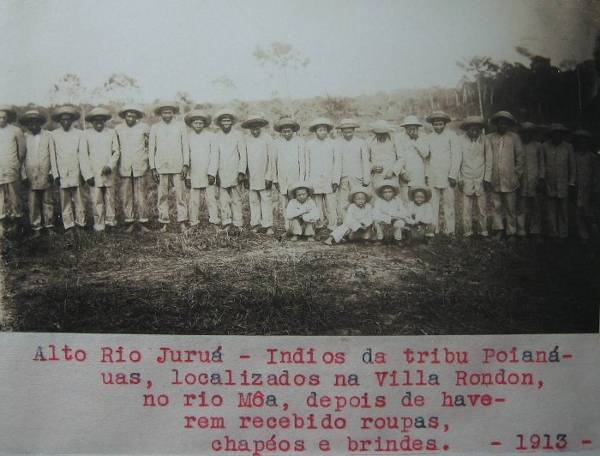

Population

The information available on the Puyanawa population indicates that there were between 200 and 300 Indians in the region in 1908. One indigenous informant stated that in 1913, the era of the first contacts with non-Indians, there were around 200 people at the Barão do Rio Branco rubber extraction area (seringal), while a second source says that 208 Puyanawa were catechized in 1913. However, this population was reduced to 115 individuals during the same year died due to conflicts and a measles epidemic caused by the rapid advance of rubber tapping activities (see Contact History). Data from 1920 to 1927 indicate a population of 125 people at the Barão rubber extraction area too.

[Marco Antônio Teixeira Gonçalves, 1991]

According to the Ecological-Economic Zoning (ZEE) Project undertaken by the Acre government in 1999 there were 403 people. The census carried out by FUNASA in 2009 showed a larger population of 529 individuals. In 2010, this number was 540 people.

Location

At the start of the 20th century, the Puyanawa inhabited the headwaters of the affluents of the lower Moa River. After the contact with non-Indians, they were forced to live on lands belonging to a prominent farmer from the region, Colonel Mâncio Agostinho Rodrigues Lima.

The Puyanawa live in two villages, Barão do Rio Branco and Ipiranga, situated in the municipality of Mâncio Lima no Acre. The main access route is the road, usable all year round. The distance between the centre of the Ipiranga rubber settlement and the town of Mâncio Lima is 28 km. The other option for accessing the area is via the Moa River.

[Constant Tastevin, 1924; José Carlos Levinho, 1984]

Contact History

From the last two decades of the 19th century, the indigenous territories rich in caucho and rubber, situated in the region drained by the Juruá and Purus Rivers, were violently invaded by groups of caucho and rubber tappers and their bosses.

In 1888, exploration by non-Indians was begun on the Moa River, an affluent of the Juruá. Four years later, the entire river, including its main branch, the Azul, was populated by non-indigenous explorers. It was during this period, 1893, that the first reports emerged of Pano-speaking Indians living on the Paraná dos Moura and Moa Rivers. Some years later, in 1905, the mayor of Alto Juruá, Gregório Taumaturgo Azevedo, reported the existence of indigenous settlements on the slopes of the Moa.

The rapid advance of rubber tapping activities in the region led to the elimination of a large part of the native population. As their territories became occupied, some groups abandoned their houses and swiddens and sought refuge in the headwaters of the rivers and in still unexplored areas. This can be ascertained from the letter sent by Colonel Mâncio Lima in which he claims that since 1900, when exploration of his properties began, he had been trying to establish contact with the Indians inhabiting the lands between the Paraná dos Moura (or the Viúva) and the Moa river without, though, any success. In a letter sent to the SPI (Indian Protection Service) in 1913, he stated that his intention was to catechize them.

[José Carlos Levinho, 1984]

First Contacts

The first attempt to contact the Puyanawa was in 1901, after the Indians had taken items belonging to rubber tappers in the region. Colonel Mâncio Lima therefore organized an expedition that included three indigenous guides. For eleven days, they trekked through the forest searching for the Indians. They were unable to locate them, although they discovered recent signs of occupation every day. They found thirteen large swiddens and five huts where they left presents.

In 1904, the Indians once again entered the houses of the rubber tappers and took tools, clothing and so on. This time some were located on a path and were unable to flee. They showed the way to the village, but when they arrived, it was already empty. Ten days later, in a new attempt, they arrived to find the village burnt to the ground.

In 1911, Antonio Bastos, an SPI officer, accompanied by Mâncio Lima’s brother, five Indians from the upper Moa, a forest guide and other assistants, tried to locate the Puyanawa. This time they just found large swiddens and empty malocas.

They therefore decided to journey up the Juruá River with the aim of bringing back some Yaminawa to help them attract the Indians, but the trip was unsuccessful. At the end of the same year a new expedition was organized, this time successful, during which they spent a night among the Puyanawa. Afterwards Colonel Mâncio Lima requested government support to catechize the Indians who had been living at the centre of his rubber extraction area for ten years.

According to the elders, shortly before being contacted the Puyanawa had divided because the number of people had increased. One group remained on the headwaters of the Preto creek, an affluent of the Paraná dos Moura, while the other, headed by the tuxaua Napoleão, moved to the Riozinho, an affluent of the Moa River. Those who stayed on the Preto creek were located by the attraction team led by Antonio Bastos. The Indians recall that they were inside the maloca when they were surprised by shouts in their own language telling them not to run. The two doors of the maloca were surrounded, but the women, frightened, managed to escape with almost all the children. The next day the men went to fetch them in the forest. Sometime later, they were all led to the Bom Jardim creek, an affluent of the Moa, where they cleared two swiddens. They stayed at this site for just a year before being transferred to the Maloca creek on the Barão do Rio Branco farm estate.

In 1913, Colonel Mâncio Lima was informed of the presence of Indians in the region by a rubber extraction area owner from the Riozinho. An expedition was sent, this time including the participation of the Puyanawa. They managed to attract Napoleão’s group, which was also taken to Maloca group.

Describing the ‘pacification’ of the Indians in the Department of Juruá, the mayor Rego Barros stated in his 1914 report that Antonio Bastos “[...] had persuaded more than eight hundred forest natives to establish friendly relations with the rubber tappers, allowing the expansion in the area being explored by the extraction industry. Meanwhile the manager [Mâncio Lima] – whose rubber production was disrupted by indigenous neighbours – after another 12 years of effort and a large expenditure of money, managed to approach them with the help of Antonio Bastos and afterwards locate more than 150 individuals from the Poyanawa tribe on his Barão do Rio Branco farm on the Moa river. Some had a beautiful physique with a number of them much taller than usual among indigenous peoples.”

The Indians remained on the Barão do Rio Branco farm for a short time since they did not adapt to the new location for various reasons, one of which was the forced work, which led to the group fleeing. Just one man was unable to escape since he was on the Bom Jardim creek. He was made to follow the trail left by the group, which had divided into three. Even so, they were located again. During the capture, the tuxaua Napoleão was shot in cold blood by Mâncio Lima’s henchman. After the death of the leader, the group dispersed, crossing the Azul River.

The other two groups were found and taken back to the rubber extraction area. Finally, the dispersed group was located by chance since the Puyanawa had used various tricks to mislead the tracker. After being captured, the men were flogged and led to the Maloca creek. As soon as they arrived, a measles epidemic decimated a large number of Indians. Those who survived were transferred to the Ipiranga rubber settlement.

[José Carlos Levinho, 1984]

The ‘captivity’ period

The period from 1915 to 1950 is named by the Indians as ‘captivity.’ The men were separated from their women and sent to the rubber settlements where they worked during the entire year: in the summer, they tapped rubber on the shores of the Moa River and in the winter, in the rubber extraction ‘centres.’ The women and the older people were responsible for agricultural activities. They planted large swiddens of maize, manioc, rice, sugar cane and beans. They were also forced to undertake long treks through the forest to transport panniers of flour and sugar, and the balls of rubber.

It was only at the end of the 1930s that the women were released from work in the swiddens and allowed to live with the men in the work settlements scattered across the rub rubber extraction area.

This period is still very much alive in the memory of the elder Puyanawa. They lived as the effective slaves of Colonel Mâncio Lima, the owner of the Barão do Rio Branco rubber extraction area. They had no right to anything, not even use of a tiny part of their ancient territory. All their lands had been taken from them. They began to do all the heavy manual work on the Barão seringal and in exchange received food and a few changes of clothing.

Indeed, it was the Puyanawa who developed the Barão seringal, building roads that linked the centre of the rubber extraction area to Vila Japiim and from there to the city of Cruzeiro do Sul. They worked the sugarcane and flour mills, felled the forests for the swiddens, sugar cane plantations and cattle pastures, cleared the rubber paths in the forest and extracted innumerable balls of rubber.

Following the death of Colonel Mâncio Lima in 1950 and the subsequent decline of the Barão do Rio Branco rubber extraction area, the Puyanawa were finally freed from slavery.

It was only after this change that the Puyanawa made the swiddens for their families, something that until then they had been prevented from doing. They continued to produce rubber, despite the crisis in the rubber economy in the region, but they were still forced to pay for the use of the rubber roads to the heirs of the old seringal owner. The payment of the ‘rubber road toll’ meant that the Puyanawa had no right to any part of their ancient territories and thus continued to live on their lands as intruders.

FUNAI only undertook its first studies to identify the Poyanawa Indigenous Land in 1977, which was homologated in 2001.

[Terri Valle de Aquino, 1985]

Cultural Aspects

Facial tattoos are common to various Pano-speaking peoples. The priest Tastevin reported at the start of the 20th century that the tattoos among the Puyanawa comprised a line extending from the mouth to the ear lobe with small vertical lines over the main line. There was a blue colour over the tattoo and around the laps. The tattoos were applied to children aged between eight and ten years, generally by elders. In the 1980s, there were still three Puyanawa Indians with facial tattoos.

Other information also recorded in the 1980s relates that during this period only the old people knew how to make baskets, bows and arrows, body adornments, sleeping hammocks and clay pots. The latter objects were manufactured for domestic and religious purposes. In the past there was a container designed to “cook the dead.”

According to Tastevin, the Puyanawa cooked the corpses of the dead for ten to twelve hours, dancing and crying. The leader divided the pieces of flesh of the deceased between the kin and other Indians taking part in the ritual. These recipients incinerated the pieces of flesh and mixed the ashes with caiçuma (a maize drink with peanuts), which were then ingested with the objective of incorporating the qualities of the deceased.

[José Carlos Levinho, 1984; Marco Antônio Teixeira Gonçalves, 1991]

Habitation

José Castelo Branco (1950) described the Puyanawa houses as single floored constructions with the lateral parts of the roof cover reaching to the ground, wall-less, with just one opening the height of a man in front and another at the rear. Built up to 100 metres in length, but fairly narrow, the houses sheltered various families, each with its own fire.

Records from the 1980s indicate that the Puyanawa resided relatively close to one another. The houses were built according to the regional style: two sloping roofs, made from timber or walking palm, and raised on stilts. The houses, which generally contained a couple with their children and a few additional family members, usually have three rooms: the ‘kitchen’ where there is an open fire, the ‘bedroom’ with hammocks or beds, and the ‘living room’ which sometimes has a table and a few stools.

[José Carlos Levinho, 1984]

In 2006, the houses were mostly built with a brick structure and wooden walls, covered with fibreglass roofing tiles with two sloping roofs. The houses in general have two bedrooms, a living room and a kitchen, and almost none of the houses possess verandas. Some houses possess a fenced yard, but the majority do not.

There are no criteria to determine who the owner of a particular area of land is. The residents close off the yard to the ideal size for their family and then tend this space. All houses have electricity. The bathroom is located outside the house and people usually bathe in the Grande River or streams. Each village possesses an artesian pool and a cistern that distributes water to all the houses.

[Fabrício Bianchini/CPI-AC, 2006]

Productive Activities

Puyanawa subsistence is strongly based on agriculture. Each nuclear family owns a swidden, producing mainly for family consumption.

They plant intercropped manioc and maize, as well as Peruvian beans, seven-week white mudubim and arigó, which are also intercropped with manioc. Rice, banana and sugar cane are grown separately. Reflecting the influence of regional society, some coffee bushes are also planted.

Integrated with the regional economy, they sell flour, chickens, eggs and pigs via the region’s commercial system, i.e. to intermediaries of Cruzeiro do Sul or settlements close to the Puyanawa community, acquiring clothing, salt and other produce in exchange.

Still in relation to trade, rubber continues to be a product sold in the region. Fishing, on the other hand, no longer comprises a perennial source of food, nor game, which information suggests has been almost non-existent since the 1970s. In addition, the Puyanawa also practice a number of activities surviving from their ancestral culture intended to maintain their welfare, trekking by foot over a wide and varied area to obtain game, water, wild fruits, raw material to make their very small range of craftwork, clay for pottery, bamboo for arrow shafts and so on.

[Sérgio Augusto de Albuquerque Gondim, 2002]

Swidden husbandry

Each village has a common swidden, divided into subareas of which each family working in the swidden owns a set. The soil to be planted is prepared mechanically with the community’s own tractor. In both villages there are also flour mills, some constructed by the government and others constructed previously by the community itself. The work of planting and processing manioc is always done in family groups, or among friends. Work is paid for by exchanging service or paid by sacks of flour or money.

The yards surrounding the houses are now being reforested due to the large number of pigs that were bred free-range in the village.

The areas of swidden are close to the village with a small area of forest before reaching them. The swidden is an extensive area of cleared land. There are also areas of pasture for cattle, fenced together with planted crops. These swidden areas are divided into 100x100m square plots, corresponding to one hectare, and each family possesses a number of areas where they grow manioc to produce flour. Generally, one area is planted, while the other is left fallow.

The land is prepared by burning the undergrowth and then harrowing the soil. Harrowing is done mechanically using the community association’s tractor, acquired through an Amazonian Development Plan (PDA) project. In 2006, each agriculturist paid sixty reais per hour to use the tractor; this money was used to pay for expenditure on diesel, maintenance and paying the tractor driver on a daily basis. Harrowing a plot takes around two hours and the land is prepared at the start of winter when the rains begin. Machines have been used in swiddens in the Poyanawa IL since 1996.

The swidden soil is sandy and many ferns grow in the area (called ‘prumas’ regionally), indicating a high level of soil acidity. The intensive use of harrowing contributes to soil erosion, as well as the practice of burning, which heavily inhibits the development of soil micro and macrolife. All this is reflected in the loss of soil fertility and consequently the fall in productivity. Crops are cultivated without any mixing with manioc. Just one variety of manioc is cultivated, white sweet manioc, chosen because of its adaptation to the region’s soil and climate. Some families also plant other crops in their yards that different from those cultivated in the swidden.

White sweet manioc is planted using seed stems, which are lengths of manioc root cut in approximately 15 cm lengths to provide good nutritional reserves. Harvesting is done with the help of the ox and cart used to transport the manioc to the flour houses. Carts are also used to collect the dry wood used in the ovens of the flour houses. Management of the swidden, harvesting and processing of the manioc are all undertaken by the families themselves or through collective work rallies.

The processing of manioc into flour is the main income generating activity of the Puyanawa community. With the support of the state government, the municipal council of Mâncio Lima and SEBRAE, two flour processing houses were built in the community. SEBRAE implemented a project supporting flour houses in the Mâncio Lima region that culminated in the creation of a flour producers association, of which some Puyanawa form part.

[Fabrício Bianchini/CPI-AC, 2006]

Political Organizations

In the 1980s, the Puyanawa had two chiefs who represented the group in negotiations with non-indigenous society. Here we can highlight the Poyanawa Agroextractivist Association of Barão and Ipiranga (AAPBI), created in 1988 to support the leadership, as well as guarantee the community access to benefits through projects with external funding.

[Sérgio Augusto de Albuquerque Gondim, 2002]

Indigenous Association

The year 1988 saw the emergence of the first indigenous associations in the state of Acre, including the Poyanawa Agroextractivist Association of the Barão and Ipiranga (AAPBI). Two years after its foundation, the Puyanawa demarcated their land with funds obtained by their leaders on a trip to the United Kingdom. The initiative, which was not officially recognized by FUNAI, was fundamental to mobilizing the community, legitimizing the Puyanawa territory in the regard of the regional population and preventing the invasions by hunters that had been occurring until then.

In the 1990s, the AAPBI was involved in various projects generating income for the community. It received financial support to fund part of the flour production sold to large buyers in Cruzeiro do Sul. However, the end of this project coincided with the disintegration of the local cooperative. The Association also administered a project for breeding and selling small livestock and from 1997 to 1999 developed a project centred on the purchase of a tractor and implements with the aim of mechanizing agricultural activities, reusing the areas of secondary growth and avoiding the need to clear areas of native forest.

In 1999, the AAPBI signed a service provision contract with the UNDP (United Nations Development Program) and PPTAL (Integrated Project for the Protection of the Indigenous Populations and Lands of Legal Amazonia) for the implementation of the “Subproject for Monitoring and Consolidating the Physical Demarcation of the Poyanawa Indigenous Land.” The project’s aim was to enable the Puyanawa and their Association to monitor the demarcation of their land, undertaken by a topography company hired by FUNAI in the first half of 2000. The Association was also responsible for putting up signs at more vulnerable points of the border paths in order to warn hunters, anglers and loggers that entry into the area is prohibited.

The project enabled the institutional strengthening of the APPBI. Its directorship and the various work teams received courses in accountancy, office administration, use of GPS equipment and record making. To support the work of the AAPBI, both permanent and consumable material items were purchased for the new head office in Ipiranga village, as well as a boat to provide support to the demarcation work and enable surveillance and fiscalization of the indigenous territory. The Association publicized the demarcation through radio programs, newspaper reports and visits to nearby farmers, associations of indigenous peoples and rubber tappers, trade unions and government bodies based in Mâncio Lima and Cruzeiro do Sul. Since demarcation and homologation of the IL, the Puyanawa have demanded more commitment from the relevant government entities to prevent the continuing invasions and illegal occupations.

[Marcelo Piedrafita Iglesias, 2001]

Sources of information

- AQUINO, Terri Valle de. A imemorialidade da área e a situação atual do povo Poianaua. Rio Branco-AC: s.ed., 1985-1 nov.

- BANDEIRA, Luiza. Monólogo Paciente. Folha de São Paul'o, Caderno Mais! 12/07/2009.

- BIANCHINI, Fabrício. Relatório da Segunda Oficina de Etnomapeamento na Terra Indígena Poyanawá. Comissão Pró-Índio do Acre (CPI-AC), Rio Branco, outubro 2006.

- CASTELO BRANCO, José Moreira Brandão. “Caminhos do Acre”. In: Revista do IHGB, vol.196, Rio de Janeiro, Imprensa Nacional, 1950.

- FUNAI. Relatório da Viagem Realizada a Áreas Indígenas. Cruzeiro do Sul-AC, 03/13/1977.

- GONÇALVES, Marco Antônio Teixeira (Org.). Acre: História e Etnologia. Rio de Janeiro: UFRJ, 1991.

- GONDIM, Sérgio Augusto de Albuquerque. “Poyanáwa: sabedoria e resistência”. In: Povos do Acre – História Indígena da Amazônia Ocidental. Ed. Fundação de Cultura e Comunicação Elias Mansour (FEM). Rio Branco, Acre, 2002. Baixe o livro na íntegra:

- IGLESIAS, Marcelo Piedrafita. Assuntos Indígenas. Consultoria contratada pelo Instituto do Meio Ambiente do Acre, da Secretaria de Estado de Ciência, Tecnologia e Meio Ambiente. Rio de Janeiro/Rio Branco, abril-maio 2001.

- LEVINHO, José Carlos. Relatório de reestudo das Áreas Indígenas Poyanawa, Nukini, Jaminawa e Campinas. s.l.: Minter-FUNAI, 1984.

- LIMA, J. F. (KIXI). Entrevista feita no II Encontro de Culturas Indígenas. Rio Branco- AC, 20/04/2001.

- MONTAGNER MELATTI, Delvair. Relatório da Viagem Realizada às Áreas Indígenas do Município do Cruzeiro do Sul. DGPC/Funai (1ª eleição da área indígena Poianáua), 1977.

- PAULA, Aldir Santos de. Poyanáwa, a língua dos índios da aldeia Barão: aspectos fonológicos e morfológicos. Recife, UFPE, 1992. Dissertação de mestrado.

- TASTEVIN, Constant. Les études ethnographiques et linguistiques du P. Tastevin en Amazonie. Journal de la Société des Américanistes, Vol. 16, n. 1, pp. 421 – 425, 1924.