Pankaru

- Self-denomination

- Where they are How many

- Linguistic family

Like many other groups in the Northeastern region of Brazil, the Pankaru had their indigenous identity recognized by the state, as well as the ratification of their lands only in the beginning of the 1990s. Their historical trajectory has been marked by a series of land conflicts with land-jumpers and squatters, which have still not been totally settled. Besides a history of marginalization and oppression by the non-indigenous society, the Pankaru share in common with the other so-called “emergent” indigenous groups, the ritual secret of the "Toré", a mark of cultural identity and resistance.

Name

Before being called Pankaru, the Indians of the village of Vargem Alegre, located in Agrovila (an organized farm settlement) 19 (created by the National Institute of Colonization and Agrarian Reform), in the Bahian municipality of Serra do Ramalho, were known as Pankararu-Salambaia. At the end of 1980, they decided to change their name to differentiate themselves from the Pankararu who lived on the Pernambuco side of the Valley of the Lower-Middle São Francisco (in Petrolândia, Itacaratu). According to the chief Alfredo José da Silva Pankaru, the change was necessary because the government agencies confused the two communities. Thus, the improvements requested by the community of Agrovila 19 were often sent on to the Pankararu of Pernambuco, a group which has been recognized for a long time by the regional authorities.

Language

Like all indigenous groups of the Northeast, with the exception of the Fulni-ô, the Pankaru presently only speak Portuguese. Only the aged patriarch Apolônio Kinane spoke the language of the Pankararu, but he didn't teach it to his children. Nevertheless, according to the chief Alfredo José da Silva Pankaru, during the toré, "praticed in the woods", several words of the ancestral language are pronounced, mixed in with the chants.

Location

The small Pankaru community consists of a group of 14 families which are divided between the Agrovila 19 and the village of Vargem Alegre, recently transferred from the "center" to the "mouth" of the forest of Serra do Ramalho, approximately 2 kilometers distant from the farming setttlement. The municipality of Serra do Ramalho, separated from Bom Jesus da Lapa in 1989, is located in the western part of Bahia, in a semi-arid region on the left side of the São Francisco River, a region which in the past was known as Beyond São Francisco.

The seat of the municipality of Serra do Ramalho lies 845 kilometers from Salvador and 40 kilometers from Bom Jesus da Lapa. The Agrovila 19, where the Vargem Alegre village is located, is 22 kilometers from the municipal seat (Agrovila 9) and about 30 kilometers from the São Francisco River.

Before the creation and implementation of the Serra do Ramalho Colonization Project (for which the INCRA created the Agrovilas, farming settlements), the region was practically entirely covered by a complex, virgin forest (brush forest, patches of stunted vegetation, and hydrophyllous vegetation), with a large swathe formed by timber of good quality such as the ipê, cedar, the aroeira, the baraúna etc. The land was fertile for cultivation and with pastures for cattle. Besides the perennial rivers - São Francisco, Carinhanha, Formoso and Corrente -, intermittent creeks and streams flowed on the mountain slopes.

In the past, the region was seen by the backland population as a kind of oasis, to which a great many of those afflicted by the constant droughts that assailed the Northeast fled, above all those coming from the Serra Geral and the Chapada Diamantina, considered less arid, and covered by dense forests and rich in animal species.

Besides the nearly 14 families of Serra do Ramalho, five Pankaru families live in Jandira, municipality of Greater São Paulo; one family lives in Goiás; seven families in Muquém do São Francisco -Bahia, a municipality which is also located on the left side of the São Francisco River.

Population

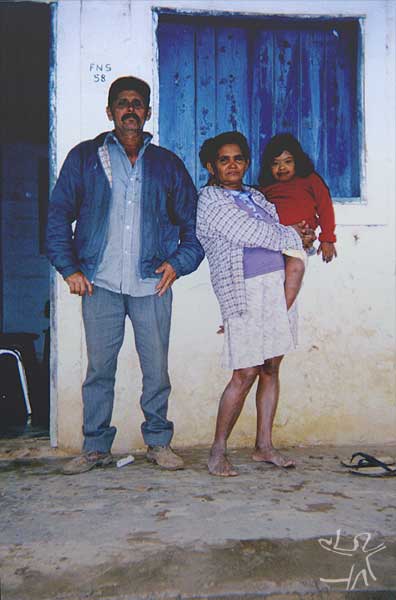

The Pankaru community is not very numerous. It is estimated that, on the Serra do Ramalho, there are 14 famílias, or approximately 87 people. Serra do Ramalho has one of the lowest HDIs (Human Development Index) of Bahian municipalities, with very high birth and death rates.

The long history of contacts with the Pankaru, as well as the reduced number of families of the community, have stimulated interethnic relations, including with members of the non-indigenous society. After the establishment of the Serra do Ramalho Colonization Project and the recognition of the indigenous community, the network of contacts of the Pankaru was considerably widened and, beyond the "Pankararu brothers", they maintained strict ties with the Kiriri of Passagem (inhabitants of Muquém do São Francisco, in Bahia), with the Tuxá (municipality of Ibotirama, in Bahia) and with the Atikum (Pernambuco). The descendants of the shaman Apolônio looked for ideal partners for love and marriage among the members of these groups.

History of contact

To reconstruct the first contacts of the present-day Pankaru with members of the non-indigenous society is an extremely difficult task, above all since it is not even known to which linguistic trunk they were affiliated. Since they are a recently differentiated ethnic group, there are no ethnographic studies on the Pankaru, and historical documents dealing with aspects of the history of the group are unknown. It is probable that the family of the ex-shaman Apolônio Kinane consists of survivors of the indigenous settlements administered by the successive religious missions established in the Valley of the Lower and Middle, between the 17th and 18th centuries. The occupation of the region of the Serra do Ramalho was connected with the expansion of the bandeirantes (slave-hunting expeditions). The bandeirantes undertook violent hunting of the Indians in the region and from there they went in the direction of Minas Gerais for the so-called War of the Emboabas. The area was connected with extensive cattle production and mining activities.

Today, the regional population is predominantly mixed, with an outstanding number of "caboclos" and survivors of quilombolas (runaway slave camps). But oral history also indicates the presence of indigenous peoples, as the testimony gathered by Father João Evangelista de Souza (n/d, 52-53) attests: "Here there were also many Indians; on the mountain, even today, there are many indigenous writings; we have found pans, pots, plates, pipes, all sorts of cooked clay, buried in these forests. The Indians used to live here, then they disappeared to the top of the mountain. I saw a pot all marked with fingernail indentations, very beautiful: it was one of their villages; we find writings and drawings on the rocks of the caverns. There, around Morro Redondo, there is a cave with a door that is closed with a wall of clay; it's full of writings on this door; no-one ever has been able to break it to see. There must be a lot of things of the Indians hidden inside there. The Indians lived here and, later, they disappeared outside. In the middle of the street, Olímpio, when he went to make a house, he found an earthen pot, full of human bones: the Indians buried their dead this way: they separated all the joints and lumped them all in a pot. These coffins and bones can still be found buried around here, one only has to look for them".

Although the publications of Father João Evangelista de Souza highlight the vestiges of indigenous presence in the region of Serra do Ramalho and Carinhanha, they do not confirm the presence of the Pankaru in the locale. It is difficult to specify the indigenous groups who used to live in the area that today covers the municipality of Serra do Ramalho. Everything indicates that they were of the Macro-Jê trunk and, undoubtedly, were exterminated and/or put to flight as cattle-ranching expanded throughout the Valley of the São Francisco River.

Life Story of the Pankaru leader

It is not an easy task either to reconstitute the process of ethnogenesis - of ethnic differentiation - of the Pankaru or their recent history. The representation of the contemporary history of the Pankaru is marked by discontinuities, elaborations and reelaborations undertaken by the pajé Apolônio and his family, seeking to meet the interests and the needs of the group.

As the Pankaru see it, the constant moves of this patriarch marked their resistance and struggle for territorialization, forging family and group identity. Thus, the ethnogenesis of the Pankaru community is strongly connected with the saga of the recently deceased patriarch and pajé Apolônio.

According to the testimony of the chief José Alfredo da Silva Pankaru, the saga of the pajé Apolônio began very early in his life. In the first decade of the 20th Century, as an adolescent, he left Lero - the village where he was born -, located six leagues from Salambaia, a region of rural Pernambuco. After wandering through various municipalities of different states of the Northeast, he made contact with the Pankararu of the village of Brejos dos Padres, municipality of Tacaratu (PE). According to the anthropologist José Augusto Laranjeira Sampaio (1992/3:9), "Already married to D. Maria, an Alagoan woman whom he met in Paraíba, he decided to settle in the vicinity of the indigenous area where he left his family while he went on his journeys. Unquestionably of indigenous origin, they were acepted as 'kin' by the local Indians". A few years later, according to Afredo José Pankaru, he quarreled with the chief and left in the direction of Paulo Afonso - Bahia.

There, Apolônio worked, in the beginning of 1950, on the construction of the Hydroelectric Dam built by the CHESF. Later, he left to work on the Hydroelectric Dam of Correntina-Bahia, as a watchguard. Delighted with the existence of dense woods in the region of Serra do Ramalho, and wanting to set himself up there, he returned immediately to Paulo Afonso to fetch his family. According to his daughter Rosália, the journey from Paulo Afonso to Serra do Ramalho was difficult and lasted several months.

In the Pankaru way of representing the story, Apolônio Kinane went into the forest in search of an indigenous community called Morubeca that he knew existed in the vicinity of the Serra do Ramalho, municipality of Bom Jesus da Lapa-BA, with which he believed he had kinship ties. When they got to the region, the Indians they sought were no longer found on the locale. They had been forced out by land-jumpers, taking to the trails and settling, according to the informant, in the territory of Goiás.

The arrival of the Pankaru at the Serra do Ramalho coincided with the exploitation of minerals in the region. According to the Indians, it was the patriarch Apolônio who discovered minerals on the Serra Solta (florite), at the end of the 1950s, and received as a reward from the municipal prefecture of Bom Jesus da Lapa, Antônio Cordeiro, the area in which he had come to settle.

In the beginning of 1970, the extreme southwest of Bahia became the scene for actions by numerous land-jumpers. A presidential decree, published in 1973, declared the region of the Middle São Francisco a priority region for expropriation. The measure was necessary because of the expropriation not only of the area of the Sobradinho Dam, but also of the area where the dispossessed population would be relocated. In view of the possibility of being indemnified, the land-jumpers became more active in the region, trying to kick out the local population who had no property titles.

The 'uninhabited' lands occupied by the family of the patriarch Apolônio then were claimed by a farmer from Pernambuco, who tormented the indigenous leader and his family, as well as the few squatters who lived in the area. A climate of terror dominated in Serra do Ramalho for, the land-jumper, seeking to throw out the squatters, threatened to tear down and burn everything they had built, and counted on the connivance of the authorities of Bom Jesus da Lapa.

Several years later, the land-jumper "sold the question" (the dispute), that is, he passed the lands on to a rancher in state of Bahia. Connected to the authorities of Bom Jesus da Lapa, the rancher used the military police of Bahia to expel the Indians. After assaulting the home of Kinane's family, they took Apolônio, a son and two sons-in-law prisoners to the police station at Bom Jesus da Lapa. According to Rosália - daughter of the old pajé -, on the way, the prisoners were taken to the headquarters of the rancher and tortured by his henchmen with the complicity of the police.

Faced with such violence, the Indians decided to go to Brasília and ask for FUNAI's help. Their contact with the agency, according to Alfredo José da Silva Pankaru, changed the life perspective of their people. Informed of their rights in relation to the lands of their ancestors, they went back to the region of Serra do Ramalho, with the intention of confronting the land-jumper. Further hostilities were recorded.

Pankaru Land and the Farming Settlements of the INCRA

In the mid-1970s, the Pankaru were taken by surprise by the news that the region of Serra do Ramalho had been selected by the National Institute for Colonization and Agrarian Reform (INCRA) for the Special Colonization Project (PEC), the purpose of which was to settle the families dislocated by the Sobradinho Dam.

Thus, an unknown number of ranches were expropriated and, from then to now, 23 farming settlements were created, occupying an area of a little more than 256 thousand hectares in the municipalities of Serra do Ramalho and Carinhanha.

The farming settlements were created to provide shelter for four thousand families, following a plan for rural engineering that needs to be explained. The area was divided up according to regional measures. Thus each family received a lot of 20 hectares (those who received land with irregular terrain got a bit more) and a house in the farming settlement situated closest to the individual's lot. A strip of 70 kilometers on the banks of the São Francisco River was set aside for irrigated cultivation. Besides that, two so-called extractivist reserves were created, to which each colonist had rights to five hectares.

In the building plan, each farming settlement would function as a rural neighbourhood which, besides concentrating the lot-owners, would provide a place for commerce, public and religious service. Among the farming settlements, only Agrovila 9 concentrated all of these services. Later, this farming settlement would become the center of the municipality of Serra do Ramalho, which was separated from Bom Jesus da Lapa.

Firm in their proposal to concede only 20 hectares to each settled family, the INCRA recommended to the FUNAI "the relocation of the Indians or their emancipation so that they may get the right to settlement in accordance with the determinations of the Land Statute" ("Reports of the Pankaru yesterday and today", n/d: 01). The Indians resisted and, after many comings and goings, their rights were recognized. What was left to them was only an area of approximately a thousand hectares, ratified in 1991, and an urban lot of three hectares located in Agrovila 19, where 50 houses reserved for the Indians were built. As the Pankaru resisted being settled in Agrovila 19, several houses for awhile were unoccupied. Thus, landless families from various parts of Bahia attempted to invade them. The Pankaru demanded intervention by the INCRA. However, the agency was incapable of preventing the "colonists" from destroying the houses, and taking shingles and blocks with them. Even today the area is disputed by the Indians and one non-Indian who declares he has property title of a lot.

A short while later, the Indians claimed that the village had become infested with bugs that transmit Chagas disease, which put the survival of the village in risk for which reason they settled in Agrovila 19, being obliged to resort to INCRA in order to obtain new dwellings; several Indians, faced by the negative response to their requests, bought houses from third parties.

Ecological and economic aspects

When they settled in Serra do Ramalho, besides agriculture for their own consumption, the Indians practiced extractivism and hunting in the dense forests that covered the mountain. The patriarch made rapé snuff and "bottles of forest remedies"; the women made crafted products - of fibres and clay. These products were sold in the markets of Taquaril, Bom Jesus da Lapa, Santa Maria da Vitória and even, Brasília, which helped in the survival of the family group.

Today, the small Pankaru community lives off unirrigated agriculture - depending on the rains - practiced in the village of Vargem Alegre, from rural retirement and from the salaries of manual labor on the ranches and in projects of irrigated agriculture installed in the region by the CODEVASF (Development Company of the São Francisco Valley).

Corn, manioc, beans - of two varieties (the "grader" and the "harvester") - as well as cotton are cultivated in small individual lots, the harvests from which barely supply needs in the following two months. Besides agriculture, several members of the community raise a few head of cattle. The lot of 14 heads of cattle acquired through a project financed by the Bank of the Northeast with the intervention of the Funai, was slaughtered or sold by its owners in moments of financial difficulty.

According to the chief Alfredo Pankaru, the community thought of developing a project for raising goats, but it was opposed by the patriarch Apolônio: "The old pajé, my father, doesn't want to have anything to do with goats. He says that goats are a lot of work, that goats go to other peoples'gardens and I don't know what else... He is darned conservative. He doesn't like goats".

After the establishment of the Colonization Project of Serra do Ramalho, with the exception of part of the area of the Vargem Alegre village, the rich and varied vegetation was totally cut down by the colonists of Incra, who in effect expropriated from the Indians supplementary sources of food.

In the last few years, the drought in the region has been constant and the Indians complain of its devastating effects, demanding from the governmental agencies the irrigation that was promised by the Incra when the Special Colonization Project of Serra do Ramalho was established in the area.

Social and political organization

Regarding social organization, there is very little difference between the Pankaru and the regional population. In general, the domestic nuclei are autonomous and cooperate economically amongst themselves. In the same way as most traditional communities, marriages between cousins of different degrees are quite common.

As far as political organization, the Pankaru are much like the other indigenous peoples of the Northeast, among whom the leading figures are the chief, or cacique, and the shaman, or pajé. The role of chief, exercised by the cacique, applies to matters that refer to collective interests, but has no importance in the domestic sphere. Thus, he acts as an external representative, exercising the role of coordinator of collective mobilization.

For many years, the patriarch Apolônio accumulated the functions of cacique and pajé. In the mid-1980s, feeling that he had become too "old", he decided to "hand over" the function of chief to an Atikum Indian who lived in the village of Vargem Alegre. Soon after, the Atikum returned to Pernambuco and Isaura, daughter of the pajé, claimed the function of chief. Isaura's claim was questioned by her brother Alfredo. "He said that it had to be a man; that he had the right because he was the oldest son" (interview with Rosália, March, 2003). Alfredo's desire finally predominated and his sister, Isaura, went to live in Goiás, later migrating to Muquém do São Francisco.

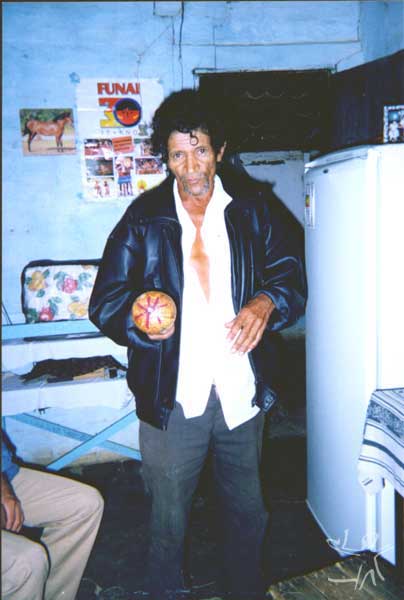

Although it is believed that the fights with the whites caused the weakening of his "science", the old Apolônio, until his death in 2002 was seen and venerated as a pajé. His son Alfredo substituted him in the role of cacique, but he has still not been identified as a new pajé.

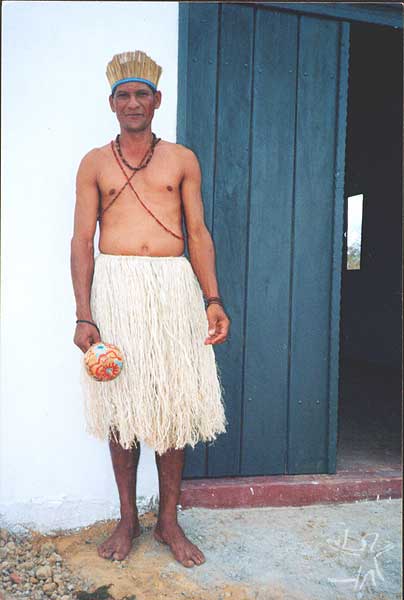

Ritual

The small Pankaru community practices the toré. The ritual has two forms which are differentiated in terms of their function and purpose. One is the "dance of the toré", a ritual which is practised as a demonstration of ethnic differentiation, and is generally presented during days of festival and commemoration, such as the Day of the Indian. Ludic in spirit, the Indians sing and dance, but they do not serve "jurema" - the sacred drink that calls the "enchanted spirits" - nor do they allow the manifestation of any supernatural entity. The other form is the "toré of the enchanted", a ritual in which the Indians demonstrate in full force the content of ethnic differentiation. This ritual is performed in the woods and, besides drinking the "jurema", the Indians receive entities and enchanted spirits. There are various kinds of entities.

The root of the "black jurema" (Pithecolobium diversifolium; Mimosa artemisiana), is only found on the banks of the São Francisco River, it is mixed in an infusion in a "wooden trough". Sometimes, portions of rattlesnake are added to the root. "When we want to do something really well-done, we put a snake inside". The chief Alfredo explains: "Take off the front, take off the back; cut up the animal and put the trunk into a trough to ferment. Leave it in the sun. When it begins to foam, take it out. It's ready". After a week, the drink is ready to be served. "The drink is good, but it is too strong. If the caboclo drinks too much, he'll fall to the ground. The white man doesn't stand it. For the Pankaru, the ritual of the toré serves to clear the mind, to give strength and unite the village. Thus, during the toré practiced in the forests the presence of non-Indians is not permitted. "Secret of the Indian, the White man can't know".

Contemporary aspects

Agrovila 19 is the poorest among all the farming settlements of this old settlement project which turned out to be a total failure. It is also the one that has the least amount of urban equipment. It has no Health Post, no school above fourth grade, nor regular transportation. The water supply is precarious and the neighbouring roads become impassable in the period of the rains (October/November and February/March). In the old village, about six kilometers away from Agrovila 19, living conditions are even more precarious: the houses were of mud walls and there were no schools.

Attending the Indians' claims, which always rejected life in the Agrovila, in 1999, the FUNASA (National Health Foundation) built a set of houses in an area located "at the mouth of the woods". The houses are made of brick and have three rooms. Besides these, a small church and a health post were built. The school which is basically for the first years of basic instruction (grades 1-4) is now in the phase of construction. Nevertheless, the Indians continue living between the new village and Agrovila 19, for the Electric Company of the state of Bahia, despite the countless requests from the Association of Vargem Alegre village, had not yet by 2003 installed electrical energy in the houses.

Notes on the sources

In the year 2000, the author of this entry published a small article in the periodical Travessia, published by the Center for Migratory Studies of the Pastoral of the Migrant, titled "Assentamentos Indígenas no Médio São Francisco: o caso dos Tuxá e Pankaru"[Indigenous Settlements on the Middle São Francisco: the case of the Tuxá and Pankaru], emphasizing the forced removal that victimized the Tuxá community of Rodelas and the removals/territorialization of the Pankaru.

Generally speaking, the reconstruction of various of the contemporary aspects of the Pankaru community could only be done by consulting the journals and the few publications of the National Association for Support to the Indian (ANAÍ)-Bahia. Two publications of the ANAI-BA provided support for this work. The booklet titled "Stories of the pankarú yesterday and today" reconstructs, in a way, aspects of the history of the Pankaru, emphasizing their resistance and conflicts with land-jumpers. The article "Seu Apolônio, the old Pankaru patriarch", by José Augusto Laranjeiras Sampaio, reconstructs the saga of the patriarch, also recording the the process of ethnic differentiation which was put into effect following the struggle with the land-jumpers.

Besides consulting this sparse material, the article was done on the basis of interviews undertaken with members of the Pankaru community(Alfredo José, Rosália, Severino and Ivone) and employees of the Indigenous Post, Josias Adelício Ramos, member of the Tuxá community of Rodelas. The interviews were conducted at different moments: in 1999 and in 2003. On both occasions it was not possible to interview the pajé Apolônio. On the first occasion, he was visiting the Tuxá community of Ibotirama, and days later he went to Brasília. On the second occasion, he had already died.

Sources of information

- ASSOCIAÇÃO NACIONAL DE APOIO AO ÍNDIO. Relatos dos pankaru ontem e hoje. Salvador : Anai, s.d. (folheto)

- ESTRELA, Ely Souza. Assentamentos indígenas no Médio São Francisco : o caso dos Tuxá e Pankaru. Travessia, São Paulo : Centro de Estudos Migratórios, n. 39, jan./abr. 2001.

- SAMPAIO, José Augusto Laranjeiras. Seu Apolônio, o velho patriarca Pankaru. Boletim Anai–BA, Salvador : Anai-BA, n. 9, p.6-7, dez.1992/jan. 1993.

- SOUZA, José Evangelista de. Do São Francisco a Serra do Ramalho. Belo Horizonte : Precisa Editora, 1991.

. De Carinhanha a Serra do Ramalho. Belo Horizonte : Precisa Editora, s.d.

; ALMEIDA, José Carlos D. Comunidades rurais negras : Rio das Rãs – Bahia. Brasília : Arte e Movimento, s.d. (mimeo)

. O mucambo do Rio das Rãs : Um modelo de resistência negra. Brasília : Arte e Movimento, 1994. (mimeo).

- SOUZA, João Evangelista; CERQUEIRA, Paulo Cézar Lisboa. Presença negra no Médio São Francisco. Caderno do CEAS, Salvador : Ceas, n. 106, nov./dez. 1986.