Matipu

- Self-denomination

- Where they are How many

- MT 189 (Siasi/Sesai, 2020)

- Linguistic family

- Karib

The Matipu inhabit the southern portion of the Xingu Indigenous Park, forming part of the network of intervillage exchanges and ceremonies that connect the ten peoples of the Upper Xingu cultural complex. Among these, the group is more narrowly identified with the other Carib groups – Kalapalo, Kuikuro and Nahukuá – with whom they are closely linked through inter-marriages and trade. This entry describes some of the specific characteristics of the Matipu. General information on the life and worldview common to the Upper Xingu can be found in the entry on the Xingu Indigenous Park.

Impressions of the Matipu

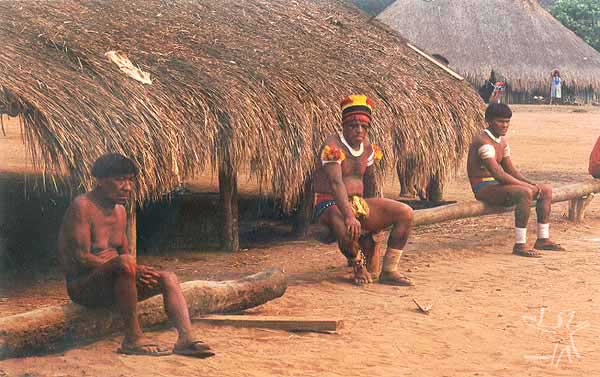

What first strikes a visitor to the Matipu is their loud laugh, open or solemn; the early morning cries of the men at the front doorway of their houses; the way women look on indulgently at their misbehaving infants; the boldness of the children, their freedom and responsibility in the domestic tasks, and the thousands of games they invent with leaves, wood, water and the animals they love to imitate. Also notable is the adaptations people make of the few grimy caraíba (white people’s) clothes in their possession, and the zeal for their extremely fine adornments, such as the shell necklaces – so carefully looked after that they always seem new.

The Matipu way of being is also seen in the seriousness with which they prepare the ceremonies marking the person’s identity – such as the Iponhe ritual for piercing the ears of adolescents descending from chiefs – along with the pleasure found in singing, dancing and making adornments. This involvement often robs many hours from the tasks of agriculture and fishing, so much so that the women complain about the time men spend in their hammocks tuning their instruments while they grate manioc for the daily consumption of ‘beiju’ (unleavened manioc bread).

Location

The Matipu inhabit a village close to the mouth of the Kulisevo and Buriti rivers, next to a lake. In 2002, a new village called Jagamü was built, also in the region of the Kurisevo river, following a political split in the traditional village, meaning there are now two Matipu villages.

Diet and medicinal plants

The Matipu basically life off fishing and horticulture. In contrast to the bigger villages, most of the residents have no access to industrialized foods from the city. Hence they basically consume fish and bitter manioc in the form of porridge or bread. The most commonly eaten fish are, in order, peacock bass, barracuda, piranha, o piau, penteado, pike characin, red-tailed catfish and sporadically matrinxã. Sometimes they hunt for turtles and their eggs, or birds such as curassows and guans, as well as monkeys. As a condiment people use homi, a small hot pepper for seasoning fish, and agahe, an ‘Indian salt’ made from an aquatic plant.

As remedies, the Matipu use knamissuá plants to heal cuts (grated, pounded and placed on the wound). Titirrerré is used for diarrhoea (cooked and ingested). Uhite, meanwhile, a plant that grows on the shores of the lake, is considered the 'Indian viagra': “used for men to be healthy.” They also possess remedies made from roots such as husago, which is used to strengthen the skin immediately after scarification. There are also a series of herbs and emetics given to adolescents during reclusion to ‘become strong.’ We can also note the combination of native remedies with the drugs employed by non-indigenous medicine.

Material culture

One of the great specialities of local craftwork is the river snail shell necklace, whose rectangular, male version is made exclusively by men. The round format – used as a necklace by women and as a belt by men – may be manufactured by both sexes.

The wooden stools are made by men and sculpted with birds, turtles, caymans and other motifs. The men also fabricate headdresses, rattles (with seeds or bells) and necklaces (using terrestrial snails, animal teeth, tree bark and seeds), as well as scrapers, baskets and other items. Canoes are made from single lengths of timber, which gives rise to their name: ‘hollowed tree canoe.’ People say that in the past canoes were made from jatobá (Hymenaea courbaril) bark, but today they mainly use jacaraúba (Calophyllum brasiliense), called katsehü by the Matipu.

Women are responsible for making hammocks – a female craft object par excellence – as well as mats woven with animal designs (turtles, caymans, birds), bracelets and necklaces made from beads and seeds (such as tucum), but primarily industrialized beads. To weave the hammocks they use string made from burity and cotton, both planted in the village itself and spun by the women.

Dance and intervillage rituals

Matipu dance is the expression par excellence of their cosmology and their way of being manifested in a ceremonial context. During rituals, people can dance like a bird, or imitate a fight with other peoples, or please the spirit responsible for a certain illness. In all cases, the mimesis effected by the dance provokes transformations in the person and in society as a whole. Consequently, dancing forms an integral and indispensable part of the education of a Matipu person. (Information on the rituals of the Upper Xingu can be found in the entry on the Xingu Indigenous Park)

The Matipu also display a degree of seriousness in their way of dancing. For them, whether or not they are invited to take part in a ritual in a neighbouring village is an important issue, since this involves power relations and, at the same time, affinity, friendship, seduction and rivalry. For this reason they take a long time producing, training and embellishing the bodies and minds to be displayed in the festivals.

Festival calendar

Matipu festivals follow the criteria of the dry season and the rainy season. The main Upper Xingu intertribal rites take place in the former. The following comprise the group’s principal dry season rituals:

Egitsu (Kwarup in Tupi): a festival that unites all the villages of the Upper Xingu system, held in homage of illustrious dead ancestors.

Hagaka (Jawari in Tupi): a festival said to be of Trumai origin, realized as a form of ‘’othering’ an illustrious dead ancestor through songs, dances and spear games. Arawak and Carib mythology suggest the festival is connected to birds, especially eagles, and to snakes, including flying snakes.

Iponhe: a ‘bird festival,’ according to mythology; the rite also involves piercing the ears of boys who have inherited the prerogatives of the Upper Xingu chiefdom, and is also considered a rite of passage to adult life.

Itão Kuegu (Jamugikumalu in Arawak and Yamuricumã in Tupi): a female festival in which women ritually occupy the space of public power and the village patio, threatening men who fail to fulfil their duties or betray their wives.

The main rainy season rites are:

Duhe: the festival of parrots, but also owls and pacu fish. This may be held between November and April.

Kagutu: this is the Upper Xingu sacred flute complex, a festival that cannot be seen – only heard – by women. It alludes to the theft of an object of power. The rite may be intra-tribal or inter-tribal. The flutes are played inside the Men's House and then around the village, while the women remain shut inside their houses, their backs turned to the source of the sound.

Takuaga: a festival typical to the Xinguano Caribs, although they themselves trace its origin to the Bakairi. In this festival, five men (consanguines) play and dance with five flutes of different sizes and pitches, representing a father, mother, two children and a grandfather. This festival may also be requested from the family of a sick person by the shaman.

Hence, the Matipu invest much of their social life in preparing and taking part in intra and inter-tribal rites, where singing, dancing and myth embody a way of being that is at once shared and a marker of identities.

Sources of information

- GALVÃO, Eduardo. Diários do Xingu (1947-1967). In: GONÇALVES, Marco Antônio Teixeira (Org.). Diários de campo de Eduardo Galvão : Tenetehara, Kaioa e índios do Xingu. Rio de Janeiro : UFRJ, 1996. p. 249-381.

- VERAS, Karim Maria. A dança Matipu : corpos, movimentos e comportamentos no ritual xinguano. Florianópolis : UFSC, 2000. (Dissertação de Mestrado)

- WÜRKER, Estela (Org.). A saúde da nossa comunidade : povos Matipu, Kalapalo e Nahukua - Livro de Ciências-Saúde. São Paulo : ISA, 1999. 38 p.