Katukina do Rio Biá

- Self-denomination

- Where they are How many

- AM 2004 (Siasi/Sesai, 2020)

- Linguistic family

- Katukina

The Katukina of the Biá River call themselves the Tükuna, a term similar to the Kanamari autonym, meaning 'people.' The two peoples speak variations of the same language and share innumerable cultural aspects, though the Katukina possess their own distinct myths, rituals and forms of social organization. Consequently, they have also had their own way of dealing with the challenges that the last 150 years have brought their way.

Location

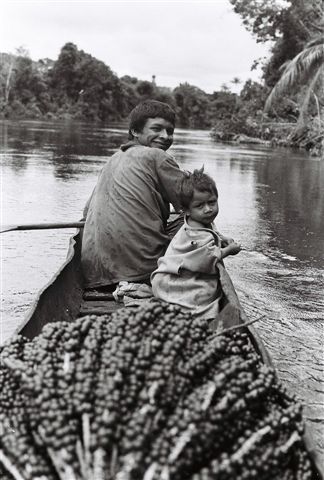

The Katukina live on the Biá river, an affluent of the Jutaí river in the state of Amazonas. The Jutaí is situated between the Juruá and Jandiatuba rivers, both affluents of the right shore of the Upper Solimões (Amazon). They number approximately 450 individuals, distributed in six villages from the mouth to the headwaters of the Biá river and its main affluent. Until a little over ten years ago, the villages were composed of a single oblong maloca called hak manya or hak nyanin (literally, ‘large house’). Today the villages are composed of houses built in the regional style on stilts and basically shelter a nuclear family (father, mother and children).

The Rio Biá Indigenous Territory covers 1,185,792 ha and was approved in 1998. The demarcation has not prevented invasions in the Ipixuna area in the far east of the territory, principally by residents of the nearby town of Carauari. River dwellers and other indigenous peoples such as the Tikuna also request permission from the Katukina to enter the IT, especially in the summer to fish. But the main place where the Katukina interact with other populations is no longer the Biá but the towns they visit to buy and sell products and to receive wages (for work as healthcare agents and teachers). This change of perspective has brought a greater knowledge of the world of the whites and a slow integration into the sociopolitical setting of the Upper Amazon, particularly the indigenous organizations.

History

Ethnonyms such as Katukina, Kanamari and Kulina have been used to designate very different peoples at various times and places over colonial history. This can be traced to the way in which the first white settlers of the Juruá classified indigenous peoples as ‘tame’ or ‘rebellious,’ the names Kanamari/Katukina/Kulina being associated with the former and Kaxinawa with the latter. Looking to escape the expeditions organized by Brazilian colonizers to capture and kill the rebellious Indians, many groups adopted the Katukina, Kanamari and Kulina ethnonyms.

The Katukina speak of a time when they lived with the Kanamari on the headwaters of the affluents of the Biá, shifting locations between the latter river and the Mutum. During this period the Katukina were nomads: they planted no manioc and their diet was based on maize and a vine, tyiwi, whose tuberous root contains an edible starch. A conflict between the Kanamari led to them leave the Biá. Linguistic data allows us to date this separation to around two hundred years ago.

The rubber period brought Peruvians and Brazilian rubber tappers to the Biá, but the poor quality latex extracted in the region protected the Katukina from invasion en masse. Throughout the 20th century the Katukina were always more numerous, but had close contact with Brazilians and Peruvians on the Biá, whether living alongside them or travelling in search of paid work. The Katukina tell many stories of when the whites came upriver with empty boats and returned fully laden with Tükuna, probably taken by force to work elsewhere.

Around 1920 the Katukina also interacted with peoples of the Upper Amazon. Kambeba, Cocama and Miranha people journeyed upriver to the Biá and some married with the Katukina. In the mid 1940s a Kanamari group, probably originating from the Mutum river, travelled down the Jutaí and settled on the Biá. They must have been fleeing from the attacks of another group and the white rubber bosses. They did not marry with the Katukina, but there were various exchanges, including of knowledge and shamanic services. Following a conflict that resulted in the death of a Kanamari man, this group moved away and probably formed the population now living on the Japurá, on the left bank of the Amazon. Later a Kulina group (madiha, in the Arawa language) settled on the Biá. Due to their fame for possessing great and powerful shamans, the Kulina are feared by the Katukina. However, after the demarcation of the Indigenous Territory, the Kulina went to settle on the lower course of the Jutaí in an attempt to obtain demarcation of their own land.

Mythology

Katukina mythology forms part of the regional complex, turning on two culture heroes responsible for creating the world, the Tükuna, other Indians and ‘whites:’ Tamakori and Kirak. In contrast to Madiha mythology and similarly to that of the Kanamari, Tamakori almost always performs the role of the wise brother and Kirak the role of the one who ruins everything. But it is Kirak’s misadventures that create the present world: for example, by crying at the death of his son, he condemned the Tükuna to never again resuscitate after death. He is seen as a child, not physically but in terms of his knowledge: his voice is childlike, forever asking his brother what they are going to do now.

The Katukina version of Tamakori and Kirak’s journey differs from the Kanamari version since it is not directly linked to the creation of the rivers and does not involve a trip downriver. The origin of terrestrial water is recounted in a myth in which Tamakori and Kirak are absent. However, Tamakori and Kirak’s feat appears, as well as the formation of the current world: the sky is produced from a piece of earth pulled out of the ground and carried upwards bit by bit to the sound of the Kohana songs (the main Katukina festival). Tamakori and Kirak also give origin to the different human populations, each people with their own knowledge, such as the cities for the whites and the Kohana and Alao rituals for the Tükuna. The Kohana was sung for the first time by Tamakori, while the Alao is the Kirak ritual. In the journey of these heroes the first woman is created too.

At the end of the myth they separate with Tamakori going to live in the east and Kirak in the west, each one with his own people. They live where the sky meets the earth from where they have no direct influence on the life of the Tükuna. They make their presence felt through the cycles of the sun and moon, commanded by themselves, or during events such as the rainbow. The rain also comes from them, the big rains from the east sent by Tamakori and the more infrequent fine rain from the west by Kirak.

Katukina mythology is not formed solely by the Tamakori cycle. Various other myths exist featuring animals in human form or humans, called pai kidak, the kinship term used for men of the great-grandparents’ generation. The themes of these myths are relations with animals, tree spirits or powerful beings such as adyaba i tyai (a child-eating ogre, literally ‘large-toothed adyaba’) and adyabatiri (owner of hunting power who gave rise to the use of tree frog [Phyllomedusa sp.] poison for propitiatory purposes). For the Katukina, these myths explain how the animals turned into their present form; in other words, they explain the differentiation of species on the basis of a world where animals possess human attributes, allowing interspecific communication.

But Katukina mythology also reflects Katukina history. For example, in the myth of Tokaneri a hero travels through the villages, transforming their inhabitants into animals depending on what they eat. The eaters of fish become giant otters, the eaters of oxi (an oily fruit) become white-lipped peccaries... This transformation is enabled by the use of a book: he simply writes in the book “who eats this will turn into that animal” and it happens. At the end of the myth he dies, swallowed by a gigantic anaconda, before transforming humanity as a whole. Another version of the myth incorporates the story of Pedro Malazarte, a figure widely present in the folklore of the Brazilian northeast, which circulated in the seringais (rubber extraction camps). For the Katukina, Pedro is an Indian who tricks the whites. The adventures are the same, the only difference being at the end when Pedro travels to the sky and meets Adam and Topana. The latter sends him back to earth to check what happened after a flood. There Pedro begins to eat the dead and transforms into a vulture, while Topana descends with the book to recreate humanity and the animals.

Cosmology and shamanism

After organizing the world as it is today, Tamakori and Kirak withdraw and no longer directly influence the day-to-day and ritual life of the Katukina. The world is maintained through the cycles of the sun, created by Kirak, and the moon, created by Tamakori. Topana is incorporated, then, into the central place that he occupies in Christian religions: in the sky, linked to the person’s posthumous fate. However this figure is unstable and his role varies according to the context: he may be an equivalent of Tamakori, or Tamakori may ‘work’ for him, or he may be in another sky, that of the whites, in which case he has no influence on the life and death of the Katukina.

The world where the Katukina live is an intermediary level between two skies and the subterranean worlds of which much less is known: there may be one or several of them... The first sky is Kodohdi, which is formed by a piece ripped from ‘our world’ by Tamakori and Kirak. It is there that the dead live, dancing and eating. It is similar to this world, containing animals, fruit and spirits. Above this is sky is Ipina, a sadder place (‘everything made of iron’), the destiny of those bitten by snakes (even if they survive), those who have been killed and the killers themselves. Beneath is the world of the Don Mïn Pönhiki, the ‘fish entrails people.’ This world is similar to that of the Tükuna, but there the water is clear and pure, and predation is limited. There the humans have white skin and hunt very infrequently, preferring to fish, and there are no jaguars or snakes. The passages between this world and that of the Tükuna are generally located around the headwaters of the creeks, called wiri mï, ‘hole of the peccaries.’ These places serve as an escape point for the white-lipped peccaries and other hunted prey. In the lower level there are also other humans, but little is known about this world since there are no accounts of anyone visiting the place, unlike the first sky and the first subterranean world.

The level occupied by the Tükuna can be divided into three macro environments: the ityonin, the forest where humans lives; the subaquatic world, the domain of the water spirits, the hïmanya; and the world inside the earth where the baradyahi spirits live. The interaction between these three environments makes up the daily life of the Katukina. The hunting domain of the humans and spirits is identical, the forest (ityonin), meaning that they are competitors. These spirits have special relations with some animals preyed upon by humans; consequently, greater care is needed when walking through the forest or paddling canoes on the river so as not to awaken their anger. In certain cases these spirits may be considered protectors of some species of animals.

The term used to designate the spirits is owei; however, this term does not just apply to the entities that live on the level occupied by the Tükuna, but also those inhabiting the celestial level. The celestial owei interact differently with the Katukina and are fundamental in the festivals.

The earth 'spirits'

The first type of spirit that can be found on the level inhabited by the Katukina are the baradyahi and hïmanya monsters. These beings do not live on the earth but can be seen hunting in the forest. The baladyahi live in the earth in large villages; they are black and use river banks to climb up to the earth surface. The hïmanyan are an aquatic counterpart of the baradyahi, provoking turbulence in the water. They are described either as giant snakes or as cattle (when they leave the water) but can assume a human appearance (especially to the shaman). Indeed various types of hïmanyan exist and this term designates either all the water spirits or a specific spirit associated with piranhas, which appears in the form of a snake. Other spirits include hïdak, the protector of the turtles, and kotomoknin, protector of the tapirs. The baladyahi were Tükuna, but in reprisal for killing and burning Kilak, Tamakoli took them to the river bank and let them drown in the mud. The hïmanyan live in the water, using the turtle as a seat, the anaconda as a rope and having alligator as their 'grandmother.’

In the forest live the owei of the trees, small spirits linked to some tall trees. They live in the tree in a couple, the male in the tree canopy and the female in the roots. These spirits are normally invisible but anyone spending a night in the forest for any reason can hear and sometimes see them. The Katukina fear these spirits because of their shamanic powers and their capacity to steal souls (wäko tan) to transform them into spirits (especially the hïmanyua and baradyahi). They are attracted by the smell of blood, which signals that a protected animal has been killed, as well as the smell of menstrual blood, which prompts the Katukina to take considerable care when butchering prey or fish (far from water since the current can take the smell to the places inhabited by spirits) and places restrictions on couples during reclusion after births or during menstruation (such as not bathing in the river and avoiding trips into the forest...).

In contrast to the others, the third type of owei found on earth is less feared, the ‘owei soul.’ This is one of the components of the person that separates at the moment of death when various ‘souls’ are released or appear, each one with its own 'post-mortem' destiny:

- wäko tan, the ‘true soul,’ goes to the sky after death where it lives as on earth. Initially it leaves the body and rises directly to the sky. While alive, it is manifested as speech, koni, and in the form of blood (mimï) and the heart (diyahkon). These emanations go to the sky since the dead person “no longer needs them.” This is the soul targeted by spirit attacks.

- owei soul is said to be a residue of the true soul that does not rise to the sky, possibly a kind of shadow or double. It can take the form of a rat and stay close to the villages, watching the relatives of the deceased and making them yearn for the latter. It can provoke light illness, principally diarrhoea, but not deliberately since it has no shamanic power.

- jaguar soul, pïda, is the part of us that likes to eat meat, visible through the ‘great blood.’ This soul will turn into a true jaguar, unless a shaman captures it.

- river dolphin soul, wapikaru, an aquatic counterpart of the jaguar soul, corresponds to the part of us that likes fish; it is visible through the wrist but not in the arms. If not familiarized by the shaman, it turns into a true river dolphin.

- neotropical otter soul, wodyon, corresponds to the wrist and veins in the arms. Like the two preceding souls, it turns into an otter if not tamed by the shaman.

The shaman’s auxiliary spirits

The shaman’s auxiliary spirits who help by spying or communicating with other shamans or in warfare are also called owei. Hence they are neither tamed tree spirits or baladyhi and hïmanyan. They are also considered shamans due to their powers of aggression. The shaman’s auxiliary owei are in fact his ‘pets,’ which involves a process of capturing or taming the various souls of the dead.

Katukina shamanism is very similar to Madiha and Kanamari shamanism, locally called ‘stone’ shamanism since they use pathogenic agents that can take the appearance of a stone, called dyohko in Kanamari and Katukina. This agent is responsible for causing illness and during cures the shaman extracts the dyohko from the bodies of patients to enable their recovery. Becoming a shaman involves learning to control a dyohko placed inside the initiate by another shaman, which allows him to communicate with the world of the spirits and to acquire more dyohko, sucking these from their patients or exchanging them with other shamans. But the difference between shamanism among the Katukina and the Kanamari is that the dyohko are not the only tools used by shamans, since they can also control and even create spirits from parts of animals, such as jaguar hairs, but especially from souls.

With the exception of the ‘true souls,’ all can be tamed by the shaman through specific techniques. To obtain a jaguar-soul, for example, he will have to fight and capture it, which is only possible for a baohi tan (baohi= shaman; tan= true). With the other souls, conversing and negotiating is enough. But this taming or ‘familiarizing’ is only the start of the process involved in converting these souls into the shaman’s auxiliaries. Once the souls are under control inside his belly, the shaman must gradually shape them, placing dyohko inside them. In the case of the jaguar, he does this to make the soul stronger and convert it into a powerful weapon that can be sent to distant places to kill. These are the auxiliary spirits that the shaman sends to spy on an enemy village or to decimate it. As mentioned above, the shaman is called baohi; however, he may also be called owei wara-hi, meaning owei ‘owner-body.’ Indeed the shaman’s power resides in the capacity to obtain auxiliary spirits and not in the collections of dyohko he may acquire.

The celestial spirits

The celestial spirits are very different to those of the lower levels since they are not species but individuals. However, they are also called owei. These spirits have specific names and appearances. For example, Kodomari is described as having a human appearance; large, white with long black hair. They are powerful and feared by the Katukina since they can send potent dyohko.

Nonetheless, they are not human-hunting gods and they descend to earth only during rituals. At each ritual one or two of these gods descend to the villages to see whether the Tükuna are conducting events properly. These gods come to watch over the festivals and consume the different unfermented drinks. They have their own life, though, and may fight until they kill each other. If the Tükuna are doing things incorrectly, they punish them by sending dyohko. This link with the festivals means that they may be named according to the festival in which they are active. Hence, in the pïda festival, the ‘jaguar’ or spirit is called pïda-wara. Here we can observe the same suffixation wara (body-owner) used to name the tree spirits.

On the first celestial level the souls live like people on earth. They dance (which causes thunder), eat, hunt and grow large swiddens with many enormous fruits. Due to the equality between the world where the true souls go and the terrestrial world, the celestial level is also home to tree spirits, but they do not interfere with life on earth. Most of the earthly swidden cultigens were brought by a celestial being who married a Tükuna woman. At death, the true soul goes directly to this world, but it can return to drink water left above the grave containing its body.

In this journey up to the sky, there is a version in which the souls arrive and are welcomed with festivals; they soon marry and live happily. This fate differs only for those who have been bitten by snakes, who will cross over this level and enter Ipina. This is also the destiny for killers of people and their victims, who arrive first to avenge their death. Once killed with an arrow, the killer falls to earth again and transforms into the mushrooms found on rotten trees. Only a smaller part of the soul returns to Ipina.

But there is also a version in which the souls do not take revenge and become the responsibility of Topana, which occurs outside of Ipina. When the souls arrive in the sky after avoiding a predatory jaguar, they are welcomed by Topana, who subsequently pierces their eyes. As it flows, the liquid from the eye transforms into rain (thunder and rainfall are taken to be a sign that the soul successfully reached the sky, had its eyes pierced and danced). In the case of killers, Topana refuses to pierce their eyes and sends them back in the form of mushrooms. Topana therefore appears as a controlling god of the sky, judging the souls of the recent dead. However, despite being allocated an important position in the sky, the figure of Topana is not present in the main event uniting the living with the celestial world: the rituals.

Rituals

Katukina rituals are key moments of communication with the upper level through the arrival of celestial spirits to supervise the songs and dances performed by the Katukina.

There are six rituals linked to the upper world involving celestial spirits:

- Kiok dyuku ritual: the celestial spirit is called yokdai;

- Barakohana ritual: Marin, very powerful and much feared;

- Kohana ritual: Kodomari, a great shaman, is the owner of obadin, tobacco snuff blown into the nose; he is happy when he has snuff and becomes angry when there is none. He is described as white with long, smooth black hair. The other owei in this festival is Baide, who lives in the sky, descending only to punish people if there is something wrong.

- Pïda (Pïdakidak) ritual: pïda-wara.

- Adyaba ritual (Adyabakidak): Adyaba(kidak)-wara.

- Arao ritual: Arao-wala and Daho. They say that Daho no longer exists since he was devoured by Pïdawara, with only his soul remaining.

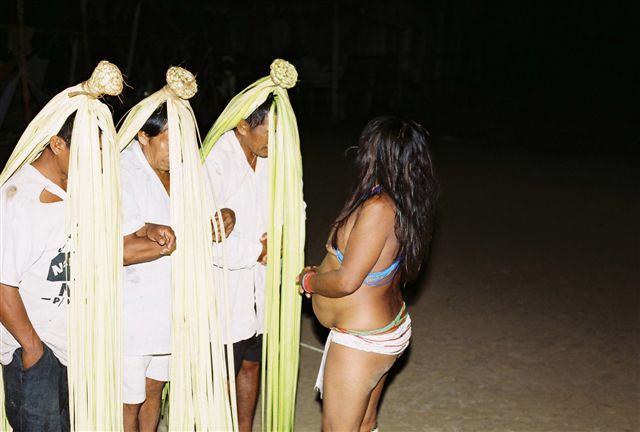

There is another ritual, pïda nyanin, but the Katukina have lost its songs. These rituals always take place at night and comprise a fixed repertoire of songs performed in a set sequence. Preparations begin with the search for food and the produce needed to make the unfermented drinks. Making these drinks is a female task, prepared with swidden products fetched by the women. When products are taken from the forest, this work is undertaken by men: the ‘body-owner’ organizer of the ritual and his near kin.

Next the men eat together on the dance clearing. Afterwards they move to the hokanin (‘clear space’), a clearing located outside the village, hidden among the alternative swidden or hunting paths. There the men eat, tell myths and stories, and dress for the festivals, using the ‘skirts’ required by the different rituals. The skirts are made on the day of the dances in the forest, always in the same place. The clearing contains the oman ton kiorikidak (oman= tree, wood; ton= on; kiori= ritual skirts; kidak= old), a type of platform made from a felled tree-trunk placed one metre from the ground, where the skirts are deposited after the festivals. There they are left to rot. This clearing is also used for much of the shamanic initiation process in which the apprentice consumes large quantities of snuff and the shaman inserts dyohko inside him. And finally the celestial spirits sleep under this ‘table’ when they visit the earth.

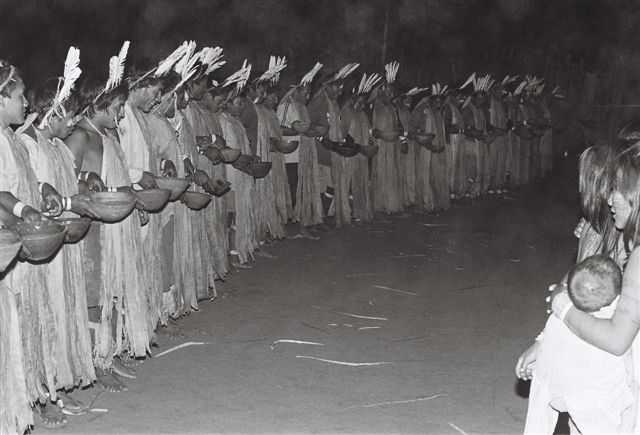

The masks for these festivals, though differing slightly for each ritual, adhere to a general pattern. Only the ‘skirts’ (as they call the festival clothing) of the Kohana ritual vary a bit more. Made from burity leaflets, they cover the entire body from head to toe. In the Barakohana and Adyabahkidak rituals, the skirt is simply a crown of burity leaflet that covers the body in the same manner as the kiori. In Kohana, the skirt is composed from three different parts made from the bark of a tree, matyiridak, and heron feathers. But the principle is the same: the tree bark is cut into strips that are hung from the front and back, covering the body; the feathers, meanwhile, serve to cover the face. At the end of Kohana, the feathers are removed and the two parts made from bark are combined and placed on the head. The result is very similar to a kiori.

The songs and dances begin immediately at sundown. The men who eat on the hokanin put on the skirts and go to the dance clearing, though not all of them will sing the first set of songs. The ‘owner-body’ of the festival takes the lead with all the songs and his close male kin, son-in-law and brother-in-law begin to sing first. Afterwards, close to midnight, all of the men will be able to sing. In the ‘dance clearing’ (a cleared space between or behind the houses), the men line up in their masks, generally with the main singer, ‘body-owner’ of the festival, at one end, who sings first while the others repeat the refrain.

When he begins to sing, his wife places herself in front of him and replies. This lasts a few minutes and then the singer transmits the song to the man immediately next him who assumes the lead of the song. At this moment, his own wife places herself in front of him, next to the main singer's wife, and starts to sing. This continues until all the men taking part have led the song – at least those who know it. During the song the lines of men and women circle around a centre formed by the singer/owner. The participants may also move backwards and forwards slightly, while the women may also strike the ground, rattling the coins on their legs or neck.

Each song lasts from one to twenty minutes according to the moment and the number of men singing. A ritual may have between 45 and 80 songs, each of which relates to an animal or a plant/tree. These songs are short and some words are repeated, giving the impression of a dialogue between the man and woman. No song is repeated in other rituals and each ritual has a set order to be followed.

As daylight approaches, the songs stop and a few ‘games’ may take place: for example, the men may enter the villages with branches laden with fruit instead of leaves and the women have to pick their husbands' fruit.

This is the general pattern of the Katukina rituals, though each has its own particularities. The ‘owner-body’ is always the same for each festival and each village has an owner for each ritual (with the exception of Kohana, the most important, which requires the participation of multiple villages). There transmission is of extreme political importance and generally each political faction within a village has a ritual singer.

While the ‘political’ owner-body of a ritual is a man, the owner-body of the ritual is, in fact, a couple formed by the singer and his wife. A single man or a single woman cannot take part in rituals and much less organize them. The rituals have a variety of origins, but the first two – the most important, serving as a model for the others, are Kohana and Arao – were given to the Katukina by Tamakori and Kirak respectively. The others are said to come from other peoples, such as Kiok dyuku (traced back to the om dyapa, a Kanamari subgroup), or from a culture hero called Kamo. The ritual songs cover a range of subjects, most of them relating to an animal or tree: in these cases, the animal or tree is said to be the owner-body of the song.

During the performance of the songs and dances, the ritual’s spirits have no direct involvement, aside from eating and drinking, but they watch the ritual and supervise it. Hence the masked men are not personifications of these spirits.

Social organization

In the indigenist and ethnological literature, the Katukina are generally known as the pïda dyapa, a name given by the Kanamari. The Katukina do not recognize this name, though the term dyapa is familiar to them. As among the Kanamari, it is suffixed to an animal name (with the exception of one case involving a tree name) in the form X-dyapa. The Katukina may also use the expression X-pönhiki. The dyapa are no longer active in contemporary Katukina social life: older people say that these segments were endogamic and localized, but Katukina history rendered them completely inoperative in terms of marriage choices and residential locations.

Nonetheless, the Katukina can be divided into three politically differentiated groups: the villages of the lower Biá (the Gato and Boca do Biá villages, which contain just over 200 people), the middle Biá villages (Sororoca, Boca do Ipixuna and Bacuri, containing just under 200 people) and the upper Biá village, extremely isolated from contact with white people. These political divisions are recognized by the Katukina, principally through their respective leaders. This separation into three blocks has a significant ritual repercussion, notably in the case of Kohana, which requires the presence of another village. Kohana is, therefore, performed in blocks with a singer per block rather than per village.

Each village has a chief, called tuxaua regionally and nohman in the Katukina language. The chiefdom is not hereditary, but derives from a choice that takes into account the man’s capacity for leadership and his knowledge of ritual, mythology and the white world.

Marriages ideally involve a couple from the same village or block; marriages between blocks are rare and generally result from a lack of internal possibilities. Katukina youths marry relatively early, in some cases before puberty, though this practice is not approved by everyone. Katukina kinship is globally Dravidian in type with a preference for marriage with cross-cousins; however the latter are unnamed, meaning they are fully on the side of affinity. Hence people say that men marry the daughter of the paternal aunt or maternal uncle (which in a Dravidian system with preference for sister exchange, as in the Katukina case, are husband and wife) rather than a ‘cousin.’

After marrying, the couple normally live in the house of the wife's father until the first child is born when they build their own house (in the villages with regional-style houses). The first child also marks an important step since divorce then becomes impossible. Indeed the couple is the basic unity of social and ritual life among the Katukina. The division of tasks between the sexes is highly important and implies a double leadership: one for the men and the group in general and one for female topics, exercised by the village’s head couple. In the rituals, the couple organizing the event can be considered the owner-body couple (wara). All the participants must be couples since songs cannot be performed without a spouse.

Notes on the sources

No specific ethnological data has been published on the Katukina of the Biá river. The only information available comes from a Funai ethnobotanical report produced by Vitor Py-Daniel and Deborah Lima in 2000 during a visit to the Kanamari of the Juruá and the Katukina of the Biá. The report contains a great deal of ethnobotanical and ethnological information, though it is not always possible to determine when the information relates to the Kanamari, the Katukina or both. The short period of time spent among the Katukina (three weeks) also limited the scope and depth of the work.

There also exists other indirect information in studies conducted among the Kanamari and specific works on the Biá variant of the Katukina language.

Finally, the author of the present text is currently completing doctoral research on the group.

Sources of information

- LIMA, D. & PY-DANIEL, V. Levantamento etnoecológico de áreas Kanamari do Rio Juruá e Katukina do Rio Bia. Brasília : PPTAL/Funai, 2000.

- QUEIXALÓS, F. “Transitividade em Katukina : uma primeira aproximação”. In: Anais do encontro Nacional da Anpoll- lingüística vol 2, pp 1063-1071.