Karo

- Self-denomination

- I´târap

- Where they are How many

- RO 414 (Siasi/Sesai, 2020)

- Linguistic family

- Ramarama

The Arara Karo live in two villages, Iterap and Paygap, both located in the southern part of the Lourdes Stream Indigenous Land, in Rondônia. Two-thirds of the Arara live in the first village, the rest in the second. The Gavião Indians, their traditional enemies, live on the same Indigenous Land. The Arara were contacted at the end of the 1940s, when hundreds of them died from contagious diseases and the survivors went to live in the rubber camps of the region. This resulted in the Arara becoming totally involved in the non-indigenous way of life, but their shamans are still recognized by all the Indians of the neighboring regions as being very powerful.poderosos.

Name

The Arara Indians are also known as Arara Tupi, Arara of Rondônia, or simply Karo (which means, in their language, “arara”[macaw]), terms which have been utilized to differentiate them from the other Arara groups of Brazil: Arara do Acre (Shawanawá), Arara do Aripuanã (Arara do Beiradão), Arara do Pará (Ukarãgmã).

In referring to themselves, the Arara call themselves I'târap, “all of us”, a word which is formed by joining the personal pronoun of the first person plural inclusive I'tâ “we”, followed by the word that has the meaning of “collective” tap (which is pronounced rap) “all”.

Language

The Arara speak the Karo language, which before was known as Arara, and which came to be called by this author Karo after 1987, so that it could be differentiated from the other Arara languages spoken by groups of the same name in Brazil.

The Karo language belongs to the Ramarama family, of the Tupi linguistic trunk (Rodrigues, 1964), and for a long time it was thought that there were other sister languages belonging to the same family: Ntogapíd (or Itogapúk), Ramarama, Uruku, Urumi and Ytangá.

Recently, however, a work by Gabas (2000) demonstrated that all of these supposed languages are, in fact, one and the same language, which received different names from different ethnologists who gathered word-lists from speakers in different periods (Curt Nimuendaju, in 1925 and 1955; Marechal Rondon, in 1948; Claude Lévi-Strauss, in 1950; Horta Barbosa, in 1945; and Harald Schultz, in 1955). Thus, the Karo language is the only language of the Ramarama family, just as other languages of the Tupi trunk are also the only representatives in their respective families: Aweti, Puruborá and Sateré-Mawé.

Socio-linguistic situation

The Arara Indians live in two distinct villages, Iterap and Paygap. In both, practically all the Indians speak their own language, and Portuguese is learned as a second language and used only as a contact language. Several Arara who were raised by families of colonists only speak the Portuguese language, but they understand perfectly well Karo. The conversations these Indians have with the community and amongst their families are conducted bilingually.

The children of the two villages are taught to speak Karo from the beginning, and although Portuguese may be learnt at a later time, one can already perceive a gradual use of Portuguese terms, mainly by the younger generations, of Portuguese terms, generally for relations of kinship(father, mother, uncle, aunt, cousin m./f.).

Several Arara also speak or understand the Gavião language, spoken by the neighboring Gavião Indians, thanks to situations of marriage among members of the two ethnic groups. The multilingualism is these cases is not looked on in a negative way, despite the fact the Arara and the Gavião are traditional enemies.

Interesting aspects of the language

The Karo language has several aspects which are of interest to scholars of non-European languages, among which I shall mention three:

The first is the occurrence of a system of classifiers, through which a classifier can occur with a substantive referring (basically) to the form in which this substantive occurs in the world (real or imaginary). A practical example is the word for “eye” that in Karo is icagá 'a', in which the first word means “eye” and the second means “round object”. The system of classifiers in Karo has ten different items, referring to different aspects of objects.

Another interesting aspect of the language is the occurrence of a system of ideophones, words generally with a very specific verb meaning and which are used to give more “expression” to stories and conversations. An example of an ideophone in Karo is the word oturum, which means “to go down to the ground making a very loud noise”, or ngârâgn, which means “turn your head around”. Ideophones in Karo are an open class, that is, they can be formed from the imagination and creativity of the speaker, hence there is a very large number of them.

A third interesting aspect in Karo is the existence of a system of evidential words, which serve to identify the source or trustworthiness of the information told by the speakers of the language. For example, if an Arara pronounced the word to'wa after a phrase, he means that what is being narrated derives from word-of-mouth, that is, he was not testimony to, nor is he supposing the fact, he is only retransmitting the information. The language uses ten different types of evidential words.

Location

Traditionally, the Arara have always inhabited the area where they live today, the Lourdes Stream Indigenous Land, in the state of Rondônia, which they share with the Gavião Indians, their traditional enemies.

The area has approximately 190,000 square kilometers, having been homologated in 1986, and is currently registered in the Federal Judiciary. Of this total land area, about 1/3 “belongs” to the Arara, the rest being set aside for the Gavião.

The closest city to the two Arara villages is Ji-Paraná, about 70 kilometers away by highway (during the dry season) or about three hours by boat going down the Machado River and entering the Prainha Stream (during the rainy season), to get to the village of Iterap. Access to the village of Paygap is easier since it is near the town of Nova Colina. By road, the village is about 50 kilometers away from Ji-Paraná.

Population

In 1987, when the author of this entry began his research with the Arara, there was only one village, which had been recently-established, and where about 100 Indians lived.

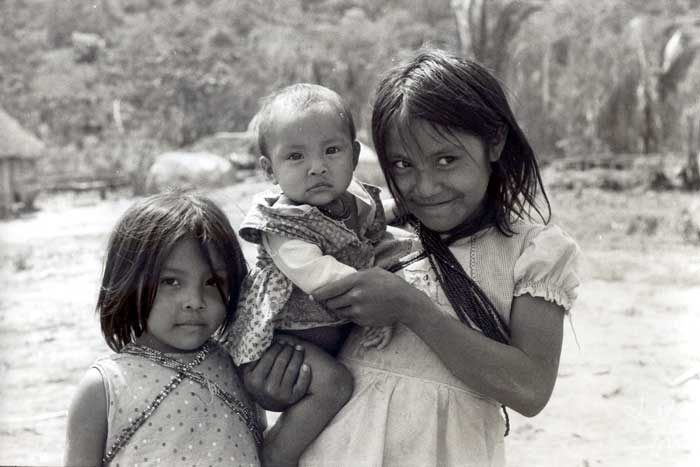

Presently, the population of the two Arara villages is estimated to be around 170 Indians, of whom 2/3 live in the village of Iterap and the rest in the village of Paygap.

There are infrequent marriages of Arara (both men and women) with Gavião Indians, and even rarer still, marriages of Arara with Zoró Indians, who live in the neighboring area. There are few marriages of Arara with non-Indians. From the linguistic point of view, the children of interethnic marriages learn the languages of both parents (Arara and Gavião, or Arara and Zoró), and later Portuguese, as a contact language.

Contact history

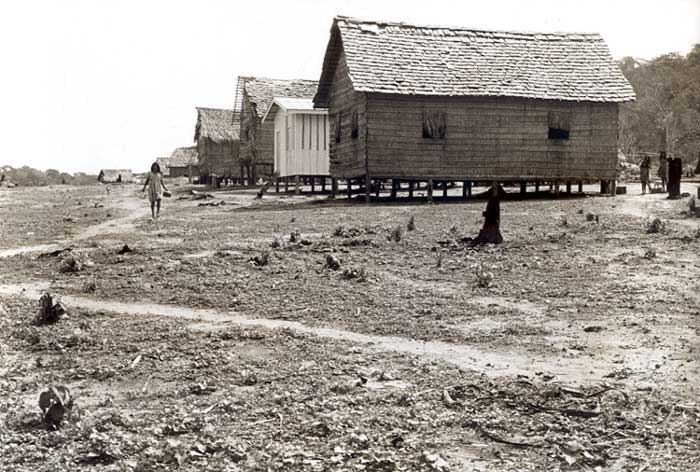

Despite maintaining some kind of contact with the surrounding population since the 1920s, the Arara were contacted by the old Indian Protection Service (SPI) only at the end of the 1940s. Contact was disastrous for the Arara communities. Hundreds of Indians died from diseases brought by non-Indians (mainly pneumonia, flu and measles), and the few who survived went to work in the rubber camps of the region, together with the non-Indian population.

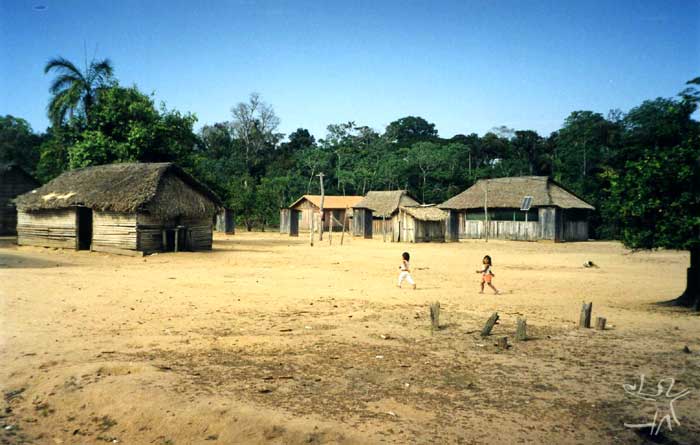

It was only at the end of the 1960s that a Funai employee, supposedly the head of the Lourdes Indigenous Post, Mr. Brígido, was able to regroup the Arara, who then came to live together with the Gavião. After many misunderstandings, in the mid-1980s, the Arara decided to found their own village, near the Prainha stream, about 5 kilometers from where it flows into the Machado River. Soon they got recognition of the village by the Funai, and the Iterap Indigenous Post was then created.

At the beginning of the 1990s there was an internal power dispute among the Arara, and the then chief Pedro Agamenon moved with his family group to another part of the Indigenous Land to establish their own village, presently called Paygap. According to the Funai technicians, there doesn’t exist a sufficient number of inhabitants in the village of Paygap to justify the setting up of another Indigenous Post.

Social and political organization

Due to the fact the Arara have been in contact with the surrounding population for a long time (approximately 60 years), their social and political organization, as well as their traditional cultural practices, have suffered considerable losses or have practically disappeared.

From what it was possible to determine from the elderly, there were traditional festivals (for example, the corn harvest festival), and there was also the seclusion of young people until the time of marriage.

There were two distinct groups of Arara: those who exist today and the so-called "Black Feet", who supposedly spoke a different dialect of Arara. Reports state that, despite their inhabiting nearby regions and maintaining good relations of friendship, there were at times episodes of animosity between the two groups, which resulted in deaths on both sides. Presently, there is no record of the existence of Indians of the “Black foot” group among the Arara.

Several aspects which are still maintained of their social organization are, for example, the fact that the man, on marrying, goes to work for his wife’s father until he decides to let them go (work, for example, in the gardens, hunting, fishing etc.). This practice is even observed among the Arara (men and women) who have married Indians from other ethnic groups, mainly the Gavião.

There are several marriages (not recent) between Indians and non-Indians, but this type of union generally is not looked upon well by the members of the community.

It is not known what was the traditional system of naming the newborn, but the Arara children receive both Arara and Portuguese names (generally names are given by the parents and/or grandparents). The meaning of the Arara name always refers to a physical aspect of the child or to an episode related to its birth (or gestation).

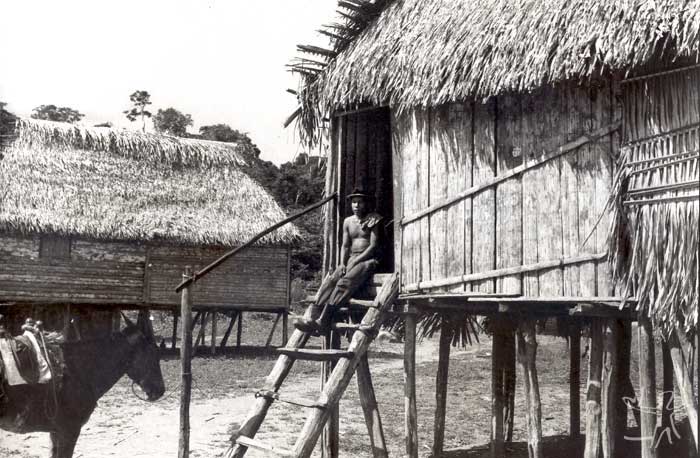

The houses of the villages are not built in the traditional architectural pattern. They are wooden houses (several already are of bricks), with a living room and two or three rooms, and the kitchen is built separately, as an attachment to the house, made of straw and paxiúba palm. It is the coolest place to stay during the day when the heat is intense.

Mythology and shamanism

Little is known of the cosmology of the Arara people. Several of the myths which have survived, however, indicate the creation of the White man from a jatobá tree; the myths still show the duality between good and evil in the form of two brothers, one virtuous and the other audacious, who ventured through the forest until the first kills the second. A collection of Arara myths, which are still remembered by the more elderly people, is in preparation and should be published very soon.

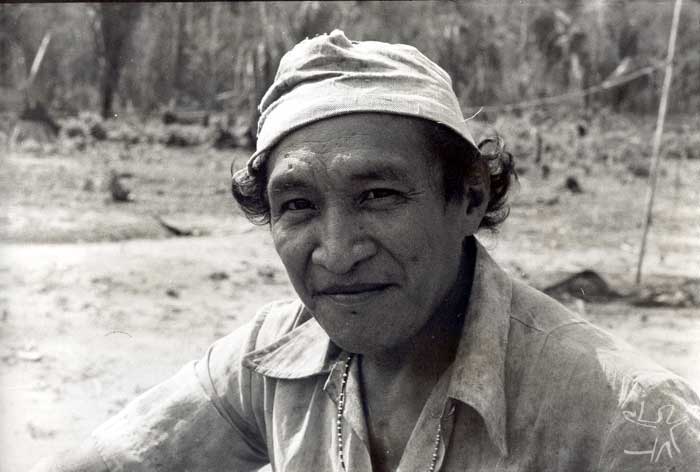

No traditional ritual is currently practiced by the Arara. There are few shamans in the village, all of them very much respected by the community and by members of other ethnic groups, but their functions in the village seem to be limited to counseling in matters relating to the community, and no longer to the activities or practices typical of their status as shaman (curing, ritual dialogues, composition of songs etc.).

Material culture

Traditional Arara art can still be seen through the making of objects, such as various body ornaments (collars with different kinds of seeds, bracelets, headdresses etc.), domestic items (basketry, tucumã and cotton hammocks, brooms, fans etc.), or hunting gear (bows and arrows). The production of clay pots no longer exists, but the women sew their own clothes (from pieces of cloth acquired in the city).

The Arara used to paint themselves with genipap dye (they would make a thin line, from one side of the face to the other), they used to bore a hole in the lower part of the nostrils where they would insert a macaw feather, and they used to use a small plug on the lower lip. Despite the fact they are no longer used, these holes can still be seen on the older Indians.

Periodically, the Indians used timbó plant poison to fish in the streams, during the dry season, and during the rains they fish with hooks or traps. There are a few Indians who still prefer to use more traditional resources for fishing, such as bow and arrow.

Hunting in general is done with shotguns. For hunting birds, principally of larger size, traditional blinds made of straw are still used.

Note on the sources

There is very little (or almost no) anthropological knowledge on the Arara. The only material published containing a small description of the life of the Arara can be found in Lévi-Strauss (1950).

Specifically on Linguistics, work (mostly lists of words) has been done since 1925, beginning with Nimuendaju. Other references are HORTA BARBOSA (1945), HUGO (1959), NIMUENDAJU (1955), RONDON & FARIA (1948), e SCHULTZ (1955).

In-depth linguistic knowledge of the Karo, however, began in 1987, when the author of this entry began his studies of the language. Since then, several articles, chapters in books and books dealing with aspects of the Arara language have been published (see the item “Sources of Information”).

At the moment, a complete grammar of the language and a Karo-Portuguese are in preparation by the author.

Sources of information

- GABAS JÚNIOR, Nilson. Estudo fonológico da língua Karo (Arara de Rondônia). Campinas : Unicamp, 1989. (Dissertação de Mestrado)

- GABAS JÚNIOR, Nilson; ARARA, Rute et al. História dos Arara no tempo do contato com os brancos : May yamat kana'xet peg xawero ma'i kanay 'mam. Belém : MPEG, 2002. 54 p.

- GABAS JÚNIOR, Nilson; ARARA, Sebastião Kara'ya Pew. Cartilha de alfabetização na língua Karo : Ak wen wen 'ya!. Belém : MPEG, 2002. 54 p.