Karajá do Norte

- Self-denomination

- Karajá do Norte

- Where they are How many

- TO 287 (Siasi/Sesai, 2014)

- Linguistic family

- Karajá

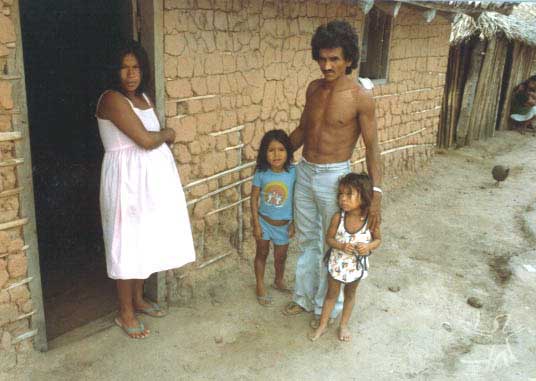

The Karajá do Norte, better known as Xambioá, live in two villages on the right bank of the Araguaia River. They speak the same language of the Bananal Island Karajá and Javaé (only portuguese), but maintain a lot less contact with them than with the neighboring non-Indian population. Due to a sharp population decline and to frequent unions with regionals, the Karajá do Norte have gone through important cultural changes. However, there seems to exist a consensus among them as to the need to implement projects and initiatives designed at rescuing the more traditional aspects of their culture and affirming their ethnic identity.

Name

Currently they are known as Karajá do Norte (Northern Karajá). Among the other groups that speak the Karajá language they are known as ixybiowa or else iraru mahãdu ("the bunch from downriver"), as opposed to the others, called ibòò mahãdu ("the bunch from upriver"), referring to their location along the Araguaia River.

The Karajá do Norte were, and still are, known as Xambioá in ethnological literature. They are called just "Karajá" by the regional population; but in the 19th Century they were often called "Xambioá", and occasionally "Karajá do Norte", by travelers and missionaries, and, more recently, by SPI and Funai staff members.

The Karajá do Norte themselves almost never use the word Xambioá when they refer to themselves. "Xambioá" comes from ixybiowa ("people's friend"), which was the name of a village that existed at the mouth of the Xambioá River, upstream from the present Indigenous Post, on the Araguaia. It is possible to speculate that the name was used for all its inhabitants and, later, to the entire Karajá do Norte population. Today the word is more commonly used for designating the region of the present-day town of Xambioá.

The self-denomination Karajá do Norte, and the abandonment of the term Xambioá, indicates their desire to identify themselves primarily with their macro-ethnic group, with a cultural matrix common to all Karajá peoples.

Language

The Karajá do Norte speak xambioá, a dialect of the karajá tongue, which belongs to the Macro-Jê branch. The language's two other dialects, javaé and karajá proper, also designate the other groups that speak karajá as well.

Location

The Karajá do Norte traditionally live on the Lower Araguaia, specifically in the vicinity of the stretch where the river has rapids. The two current villages, Xambioá and Kurehe, both located in the municipality of Araguaína, in the State of Tocantins, are built on the right bank of the Araguaia, 6 kilometers away from one another. They are 100 kilometers upriver from the town of Xambioá, 150 kilometers by dirt road and paved highway from Araguaína, and 70 kilometers from Santa Fé do Araguaia, which are the most important urban centers for the Karajá do Norte.

In 1888 the Karajá do Norte lived on four large villages between the Pau d'Arco rapids (close to the present-day town with the same name) and the "big falls of São Miguel". Their hunting expeditions, however, took them to the vicinity of São Vicente do Araguaia (present-day Araguatins), from where they were expelled by colonization. The area they occupied in the beginning of the 20th Century stretched from 7° 30' South to 5° 50' South, that is, more than 240 kilometers along the Araguaia River.

Around 1920/30, the Karajá do Norte population was spread around some eight villages. In addition to them, other places are mentioned by different sources, but it is unknown whether they were traditional areas of villages or were being used because of the interest in having contact with newcomers. Such is the case, for instance, of the small villages that were established for a while near the 'garimpo' (mining field) Pedra Pedra, in the place called Karabitxana. After the great reduction in their population, the remaining Karajá do Norte were scattered in places distant from each other, such as Araguanã and the village at the mouth of the Cabiriru River.

A large part of the inhabitants of these villages was grouped together by SPI in the 1940s in the vicinity of a place called Água Fria, name of a left bank tributary of the Araguaia River, just to the North of the limits of the current Indigenous Land, where an Indigenous Post was going to be established for the group. To that first, failed attempt by SPI there followed another, this time at the Cabiriru village (Kabiriry, which means "road of the bacaba palm tree"), located on at the mouth of the Cabiriru River, on the Southern limit of the present-day Indigenous Land, which failed too. Still in the 1940s, the SPI Post and the Karajá population that lived in it were transferred to the place where they are now, between the Matinha River and the Paca creek. The following step was the definitive reunion of the inhabitants of the remaining villages and of the families that lived with the regional population along the river. There they remained together until the summer of 1985, when just over half of its population decided to move to Kurehe hawa, six kilometers from the Xambioá Indigenous Post. By 1987, it looked like the Karajá do Norte would remain divided into two groups, with equivalent number of inhabitants, at the same time that a slight population growth, that continues today, was taking place.

The Xambioá Indigenous Land, with 3,326.35 hectares, reserved and physically demarcated since 1979, holds the entire Karajá do Norte population. Homologued in 1997, it is registered in Araguaína's Cartório de Registro de Imóveis.

The Xambioá Indigenous Land, however, represents only a fragment of the territory traditionally used by the Karajá do Norte in their activities of fishing, hunting and gathering food and materials. Its small size causes the Indians to be regarded, surprisingly, as 'invaders' by the alleged owners of areas they continue to use as they always used in the past even though they no longer belong to them. Today, for fishing the Karajá do Norte use lagoons and other water holes rich in fish that are located outside their lands. They also gather food outside their limits. The materials needed for their arts and crafts have to be bought from the regional population that now occupy their traditional territory.

Population

The present Karajá do Norte population is 185 people, according to an October 1997 survey carried out by Funai's Health Department of the Araguaína Regional Administration.

This population live in two villages: 95 people in Xambioá and 90 in Kurehe. It is composed primarily by Karajá do Norte, in addition to a few regionals, most of who joined the group in the 1950s. There are also a few Mbya-Guarani who married into the Karajá do Norte in the 1980s, the remnants of a few dozen Guarani Indians who also lived in the area at that time.

The size of the present-day population does not reflect what it had been up to the end of the 19th Century, when the Karajá do Norte numbered some 1,350 individuals. Since that time the group went through an extremely violent process of population loss, which reduced it to just 40 people in 1959, only between 3% and 4% of what it had been five or six decades earlier.

The increase in the total population of the two villages, from 135 in 1987 to 185 in 1997, even in spite of the removal of most of the Mbya Guarani from the area, indicates that the Karajá do Norte population is slowly beginning to recover, and points to a growing tendency of members to look for partners within the group, suggesting at what might be the end of the period of unions with regionals.

Currently, given the large number of young people under 15 and thanks to regular health assistance, it is possible to forecast the continued growth of the group, albeit in a slow rhythm.

History of contact with other indigenous groups

The Karajá do Norte have had historical relations with several Kayapó groups (Xikrin, Metuktire and the extinct Irã-amrãire from Pau d'Arco), Timbira (especially the Apinayé) and Akwen (Xerente, mostly in the 19th Century).

In the 19th Century, these relations were mostly hostile, with the exception of short-living alliances with the Xerente against military garrisons, and were caused by the displacement of the local Indigenous groups due to the arrival of colonists. There are reliable evidences, however, that in past centuries considerable social exchange had taken place, especially with the kayapó groups, among them the Xikrin - who still practice rituals learned from the Karajá do Norte - and the Metuktire, who maintain many objects of their material culture, in particular basketry and feather items, also 'imported' from the Karajá do Norte. According to anthropologist Terence Turner, the Metuktire refer to the Karajá do Norte as a sort of 'mother culture', which indicates the depth of the contacts between those Indigenous groups.

Still in the 19th Century, the Karajá do Norte maintained mostly hostile relations with the Tapirapé, a Tupi-Guarani-speaking group, when this people moved past marginal areas of the Araguaia River in its movement southward.

History of contact with Brazilian society

It is probable that the Karajá do Norte have been attacked by slave-hunting expeditions from São Paulo in the colonial period, but they were not their preferential target. Thus they managed to reach the 19th Century relatively preserved and were considered the most numerous among the karajá groups. Their contacts with 'whites' were limited to traffickers, missionaries and adventurers who reached the Lower Araguaia coming from Pará.

During the Fernando Delgado administration (1809-20), a Karajá do Norte delegation went to the seat of the Captaincy of Goiás to ask to be 'aldeados' (put in villages). The governor, however, ignored them, because at the time the governmental 'aldeamentos' were completely abandoned in Goiás.

Perhaps the reason for sending emissaries was more a wish to find a way to accommodate life alongside the colonists and military garrisons that were installing themselves on the Lower Araguaia then a true desire to be transferred to real 'aldeamentos', which, by the way, they must have been familiar with through the other karajá groups that already lived in them. Be it as it may, the efforts made by the Karajá do Norte to establish normal relations with Brazilian society were not taken into account at the time.

The conflicts between the Karajá do Norte and local military garrisons, that were to last until the end of the 19th Century, began in 1813. In that year, allied to Akwen groups, probably Xerente, the Indians destroyed the Santa Maria prison.

In the second half of the 19th Century, the attacks of the Karajá do Norte to military garrisons, mostly those of Martírios and Santa Maria, became more frequent. There were also armed clashes in the Xambioás Mission, where once a Capuchin missionary commanded the counter-attack of the local military detachment, which resulted in the death of about 30 Indians.

The attacks carried out by the Karajá do Norte were primarily against the military, with whom the Brazilian presence in the Lower Araguaia was affirmed: prisons, camps, detachments and boats, even armed convoys, were targets of the Indians. On the other hand, the pioneer non-military nuclei, especially because of their (relative) weakness vis a vis the surrounding larger Indigenous population, certainly did not assume an openly hostile behavior towards the Indians.

Between the last years of the 19th Century and the first of the 20th, the Karajá do Norte suffered enormous population losses, mostly due to diseases, but, in a smaller scale, as a consequence of armed clashes with military garrisons as well. So eventually they no longer represented an obstacle to shipping and to the establishment of pioneer civilian nuclei in the Lower Araguaia. Ironically, when that happened the plans for shipping and colonization in the region had been abandoned. The main consequence of the policy of aggression directed towards the Indians is the population void that today exists in the Lower Araguaia, the result of the extinction of their villages. Currently the Karajá do Norte are more than 250 kilometers of river away from the closest Karajá village.

In the first decades of the 20th Century the Karajá do Norte lived in some eight villages, which they occupied basically in the 'winter' (the rainy season, from November to March), during which they dedicated themselves to agricultural activities. The rest of the year they lived on the beaches, exploring the river and maintaining contacts with Southern Karajá groups, which then were scattered and that later formed the villages of Macaúba, Lago Grande and Javaé de Kanoano, as well as with other Indigenous groups (basically Kayapó) and with the regional population.

The small scattered Karajá do Norte family groups were already experiencing, at the time, intense population loss, caused by the violent irruption of diseases imported from the regional population and by the lack of assistance from the SPI and local religious missions.

In the 1940-1950 period, with the objective of founding a Post, an SPI representative visited Kabiriry village. Because the village port was inadequate for docking ships, he convinced its inhabitants to move to where the present-day Xambioá Indigenous Post is. After the Post was installed, an effort was made to group together the inhabitants of the other villages and the families that lived in contact with regionals settled along the river. The objective was to make sedentary this population that was constantly on the move and thus make easier the work of assisting it. Houses were built, large 'roças' (planting fields) were opened and a tile factory was built. But this first Karajá do Norte 'aldeamento', formed by the reunion of the inhabitants of several local groups, did not last long. Because of quarrels and internal dissentions, its inhabitants dispersed.

At that time, the Karajá do Norte were in contact with the 'regatões' (merchants who sail the rivers of the Amazon Region), to whom they sold fresh and salted fish, especially salted filets of pirarucu (a very large freshwater fish common in the region), in addition to skins of various wild animals, particularly large cats and otters. In exchange they got, among other items, 'cachaça' (firewater, a strong sugarcane liquor).

Tensions and conflicts among the Indians, which had so far been avoided thanks to the circulation of individuals and families through different villages, burst open when they were put together and were subjected to daily contact. From a situation of politically autonomous local units, the different Karajá do Norte groups had to adjust to a radically different situation: several of their leaders, along with their family segments, had to accommodate and accept the authority of a 'captain' picked by the SPI. The frequent quarrels and arguments were made worse by the routine consumption of alcohol.

The internal situation of the recently formed village quickly deteriorated, causing the dispersion of its inhabitants, who returned to the places where they lived previously. The dismantling of the Post and the end of the assistance it provided was also a factor for the dispersal.

In the early 1950s, besides returning to the places where they had lived until the beginning of the 1940s, many families started to maintain contact with regionals, after installing themselves close to non-Indian settlements on the river. The first matrimonial unions with members of the regional population took place then, but left no descendants. At the same time, frequent deaths continued to occur, caused by diseases and by the lack of medical care.

In the mid-1950s the SPI made a second attempt. Members of its team visited all the places where the remaining Karajá do Norte lived and convinced them to group together once more.

At the time 14 unions with non-Indians from the region were celebrated. In 1982 nine regionals (five men and four women) married to Karajá do Norte individuals lived in the region. In 1980, the group was joined by some twenty Guarani-Mbya coming from the State of Mato Grosso do Sul and probably from Paraguay, three of whom married into Karajá do Norte. On the other hand, few unions with Karajá and Javaé took place because of the distance from their villages. It was the incorporation of the regionals and of the Guarani that made population recovery possible for the Karajá do Norte, preventing their physical extinction in the 1960s, when they were reduced to only 40 individuals, due to diseases, alcoholism and internal strife.

Regular medical assistance and the definitive permanence of the Karajá do Norte close to the Post in order to make treatments easier also had positive effects in population recovery, by managing, in the end of the 1960s, to halt the devastating consequences of epidemics among the Indians.

During the 1970s, Funai improved the infra-structure for the Karajá do Norte with the construction of houses for the Post and the training of a few members of the group as bilingual monitors, nurse helpers etc.

After the Karajá do Norte were established in their Indigenous Land, neighboring landowners attempted to invade the area several times; the Indians, on the other hand, got involved in making business deals with timber companies.

In 1985, because of internal political disputes, a dissident group founded Kurehe village, 6 kilometers downriver from the Post.

Social organizations and the environment

Like the other Karajá-speaking groups, the Karajá do Norte establish what would correspond to our seasons according to regime of the river waters: 'the beginning of flooding', 'flooding', the period between the end of the flooding and the beginning of draining, when the level of the water remains constant (behetxi), 'the time of new beaches' (draining) and 'the time of beaches' (dry season).

Their religious manifestations, as well as their forms of social and political organization, are centered on their relationship with the river during the seasons' cycles. Each season presupposes very definite rhythm and social activities. Rainy and dry seasons do not mark just well-differentiated regimes of subsistence, but also the arrival and departure of supernatural beings, expected and received by the karajá-speaking groups along the year, and the movements of reunion and dispersion of the villages, which result in singular social forms for each period.

The manageability of this social and religious system, capable of 'working' successfully both in small camps on beaches and in large villages, differentiate the Karajá do Norte from the Jê groups of Central Brazil, which possess a social morphology that requires large villages in order to fully work.

The karajá-speaking peoples see themselves as belonging to kinsfolk of living (wasy) and dead (wabàdè). The entire karajá territory is closely related to the dead kinsfolk who once occupied it, recognized by the names of their ancestral male leaders. The living kinsfolk which occupies it at present evoke the names of such ancestors to affirm their rights over parts of such territory. The Karajá organize themselves basically in extended families, which are parts of kinsfolk with territorial expression, organized in factions with high potential for parting vis a vis the community in which they live. Their smallest villages can be inhabited by a single extended family, in which in general a father-in-law lives along with his sons-in-law's families; the large ones are inhabited by a group of kinsfolk formed by several extended families. Members of such kinsfolk may usually be scattered around several villages, something that prevents hostilities among them.

In addition to those semi-permanent divisions, the Karajá, Karajá do Norte and Javaé villages experience, once a year, a relative dispersion of their inhabitants during the 'summer' (dry season). Although this phenomenon was more intense until de 1950s and 1960s, it still occurs, at least partially, in the majority of their villages. In order to better explore the resources the river makes available at that time of the year, the population of the large villages split into smaller social units, which can be composed from a single nuclear family to several allied extended families. Spreading themselves into beaches, 'furos' (channels that connect rivers or a river and a lake) and lakes, and going up tributaries of the Araguaia, they explore with great mobility the vegetal and animal species that the season offers. Thus the 'time of beaches' is subdivided into 'the time of the turtle and its eggs, of the tracajá (a type of freshwater turtle) and its eggs', 'the time of the crumatá' (a kind of Amazon fish) and so on.

Religion and annual cycle

The religious system of the karajá-speaking groups, through an elaborate ritual system, manifests itself during the summer in the ijasò anaràky, since it ensures the contact of the community with its faraway ancestors, the ijasò, masters of the sky, the water and the land animals. The acts of the shamans, of the organized community and of the ijasò make possible for the village to get food. Conceptually, the karajá-speaking peoples are nurtured through the renovation of such alliance with their past. The conception that subsistence is ensured, among other things, by a correct religious attitude, marks a traditionalist, commonplace vision regarding the availability of natural resources.

When the rainy season starts and the river waters begin to rise, the Karajá group together in the larger villages along the Araguaia. This is the time for hunting, for the preparation of the land for planting, for corn, for harvesting and for gathering several plant species.

Because of population loss and of the changes occurred in their life conditions in general, the Karajá do Norte have simplified their ceremonial life. They kept, however, the celebrations of male initiation, held annually on April 19, Brazil's Indian Day. In this ceremony, which marks the passage from the stage of 'boy' to that of 'young man', the village is visited by representations of kàralahuni, 'Kayapó warrior spirits' (killed in combat against the Karajá do Norte), who associate themselves with those being initiated as protecting spirits. The kàralahuni are fed by the families of those being initiated, which serve them korotxu, a 'beiju' (tapioca paste) cake stuffed with chunks of fish. Like the other Karajá-speaking groups, the Karajá do Norte emphasize the importance of male initiation by performing it between the peak and the end of the rainy season.

Political life

Extended families, which alone or in coalition live independently during the summer, are the base and the limit of the political system of the karajá-speaking peoples. Their annual reunion in the rainy season causes a considerable increase of the political activities, through the establishment and renewal of a complex system of alliances, in which factions are made and unmade and leaderships are consolidated while others are removed.

Such intense political activity generally results in the formation of new villages by factions that end up finding themselves in disadvantage. The establishment of religious and governmental agencies among the karajá-speaking peoples in the 20th Century opened up a new set of topics to be negotiated among the different extended families grouped in factions. After this happened, the control of Funai's apparatus, of the jobs, of the interface with 'whites' and of the opportunities and advantages offered to the group have become an objective of the parties involved in this political dispute. Thus the formation of the present-day Kurehe village was just one more demonstration of the persistence of traditional politics among the Karajá do Norte, in which the losing factions have to accept a situation of submission or look for another place to live.

Today the main factions of the Karajá do Norte are still linked to the leaders of the extended families who allied among themselves at the time Xambioá village was formed. The link of present-day inhabitants with the 'original' family groups that formed the village seems to remain a strong reference today, as the maintenance of the names of those 1940s and 1950s family leaders as 'surnames' of the present-day Karajá do Norte seems to indicate. Nowadays, 'typical' names are composed by (1) a Portuguese name, followed by (2) a Karajá do Norte name, (3) the family surname (the name of the most important person of the family faction: Txebwaré, Axure etc.) and (4) the 'ethnic' surname (Karajá).

Considering the expected population growth and the permanence of this cyclical mechanism of division, the formation of new Karajá do Norte villages can be forecasted. With more people in their territory, and given the scant resources of their Indigenous Land, a progressive increase in the conflicts between the Indians and neighboring farmers is to be expected.

Insertion into the regional economy

The lack of enough materials in their present area that can be used in the manufacture of crafts, both utilitarian or for sale, forces the Karajá do Norte to get into a costly commerce of raw materials with the regional population. In order to make arrows, for example, they have to buy the 'taquari' (a type of bamboo), sold by the 'touceira' (bush) in Pau d'Arco. They can also get the 'taquari' by means of the system called 'à meia' (half and half), in which half of the arrows produced is given to the person who furnished the bamboo. The 'taquari' can also be obtained on the headwaters of the Matinha River, outside the Indigenous Land. The 'imbé' (a type of fiber), used for tying up the tip of the arrow to the stem, is obtained from the Tapirapé and the Javaé, or else on the headwaters of the Maria River, where it is sold by the meter. The 'mulungu' (coralbead) or olho-de-cabra (goat's eye) - a black seed used in necklaces, bracelets and earrings - can be obtained on the Pará margin of the Araguaia, or is bought by the bag. The straw from the buriti palm - essential for making mats, baskets and roofs of residences - is bought from small farmers in Pau d'Arco and Araguaína, and are paid by the 'molho' (bunch). Also the 'pati' (queenpalm), used for making bows, is gotten on the Pará side of the Araguaia.

In spite of the difficulties for getting the material needed to manufacture their artifacts, the Karajá do Norte sell their production regularly to the regional population. They are mostly objects of practical use, such as 'moringas' (water jugs) and oars, which makes these Indians different from the other karajá-speaking groups, which specialized as producers of 'tourist' arts and crafts.

Although they are familiar with techniques for the elaboration of sophisticated pieces of feathery art and have access to bird feathers, the manufacture of more elaborated pieces is relatively rare among the Karajá do Norte due to the lack of buyers. Instead they prefer to concentrate their production on low cost items such as necklaces, 'testeiras' (a decoration piece that covers the forefront) and rattles.

The Karajá do Norte's involvement with the regional economy is relatively unimportant because of the distance from economically significant centers and the absence of development poles nearby. Jobs tend to be linked to the State secretaries of Health and of Education, to Funai, retirements from Funrural (a government fund for the retirement of rural workers), the sale of fish and arts and crafts and the sporadic sale of their workforce to neighboring 'fazendas', which make it possible for them to buy industrialized products (salt, textiles, sugar, flour, rice, oil, metal items, fishing gear, kerosene).

The Karajá do Norte sell small amounts of fish to the 'garimpos' and 'corrutelas' (small clusters built by 'garimpeiros') situated in a 30-kilometer radius, as well as in Araguaína. Nowadays they no longer sell salted pirarucu filets, as they used to until the mid-1960s, when the 'regatões' sailed along that stretch of the Araguaia River.

From April to June, some Karajá do Norte engage in forest clearing in the region's farms. Sporadically some of the men work as peons on neighboring rural establishments for limited amounts of time.

Note on the sources

There are very few published works that deal with the Karajá do Norte. The German ethnologist Paul Max Alexander Ehrenreich visited the group in 1888. The extensive material about this visit, organized into material culture, mythology and mask dances, collected among the Karajá do Norte and the Karajá, was published in Berlin in 1891. In Brazil it was published with the title of Contribuições para a Etnologia do Brasil, with translation by Egon Schaden and published by the Revista do Museu Paulista, new series, volume II, São Paulo, 1948.

The next cultural ethnographic characterization of the group appeared in 1992, with the thesis of the São Paulo anthropologist André Toral about the Karajá-speaking peoples. In it, the history, population and social organization of the Karajá do Norte are studied through bibliography and field studies made in 1982. The work is called Cosmologia e Sociedade Karajá (Karajá Cosmology and Society) and is a Master's Degree thesis presented to the Programa de Pós-Graduação em Antropologia Social do Museu Nacional da Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro (Graduate Studies Program in Social Anthropology of the National Museum of the Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro) in 1992.

Sources of information

- AZAMBUJA, Elizete Beatriz. O índio Karajá no imaginário do povo de Luciara-MT. Campinas : Unicamp, 2000. 144 p. (Dissertação de Mestrado)

- BALDUS, Herbert. Mitologia Karajá e Tereno. In: --------. Ensaios de etnologia brasileira. 2a. ed. São Paulo : Ed. Nacional ; Brasília : INL, 1979. p. 108-59. (Brasiliana, 101)

- --------. A mudança de cultura entre os índios do Brasil. In: --------. Ensaios de etnologia brasileira. 2a. ed. São Paulo : Ed. Nacional ; Brasília : INL, 1979. p. 160-86. (Brasiliana, 101)

- --------. Tribos da bacia do Araguaia e o Serviço de Proteção aos índios. Rev. do Museu Paulista, São Paulo : Museu Paulista, v. 2, n.s., p. 137-68, 1948.

- BONILA JACOBS, Lydie Oiara. Reproduzindo-se no mundo dos brancos : estruturas Karajá em porto Txuiri (Ilha do Bananal, Tocantins). Rio de Janeiro : Museu Nacional, 2000. (Dissertação de Mestrado)

- BRAGA, André Garcia. A demarcação de terras indígenas como processo de reafirmação étnica : o caso dos Karajá de Aruanã. Brasília : UnB/DAN, 2002. (Monografia de Graduação)

- BRESIL : Arts prehistoriques, la conquete portugaise et l'art baroque, cultures indiennes, de l'esclavage a l'ere industrielle. Paris : SFBD Archeologia, 1992. 77 p. (Dossiers d'Archeologie, 169)

- BRIGIDO, Suely Ventura. A poética dos ritmos e dos movimentos caóticos : uma leitura do espaço e do tempo, a partir dos conteúdos estéticos e culturais dos índios Karajá. Rev. da Academia Nacional de Música, Rio de Janeiro : Academia Nacional de Música, n. 11, p. 61-76, 2000.

- BUENO, Marielys Siqueira. Macaúba : uma aldeia Karajá em contato com a civilização. Goiânia : UFGO, 1975. 92 p. (Dissertação de Mestrado)

- CHIARA, Vilma. Les poupées des indiens Karajá. Paris : Université Paris X, 1970. 175 p. (Tese de Doutorado)

- COMASTRI, Elane R. Martin et al. Plano de Manejo : Parque Nacional do Araguaia. Brasília : Ministério da Agricultura/IBDF/FBCN, 1981.

- CONRAD, Rudolf. Weru Wiu : musik der maske weru beim Aruana-Fest der Karaja-Indianes, Brasilien. Bulletin de la Soc. Suisse des Américanistes, Genebra : Soc. Suisse des Américanistes, n. 61, p. 45-61, 1997.

- COSTA, Maria Heloisa Fénelon. A arte e o artista na sociedade Karajá. Brasília : Funai, 1978. 196 p. (Originalmente Tese de Livre Docência na UFRJ, 1968).

- --------. Representações iconográficas do corpo em duas sociedades indígenas : Mehinaku e Karajá. Rev. do Museu de Arqueol. e Etnol., São Paulo : MAE, n. 7, p. 65-9, 1997.

- --------; MALHANO, Hamilton Botelho. A habitação indígena brasileira. In: RIBEIRO, Berta (Coord.). Suma Etnológica Brasileira. v. 2, Tecnologia indígena. Petrópolis : Vozes, 1986. p. 27-94.

- DIETSCHY, Hans. Cultura como sistema psico-higiênico. In: SCHADEN, E. (Org.). Leituras de Etnologia Brasileira, São Paulo : Companhia Editora Nacional, 1976. p. 315-22.

- DONAHUE JUNIOR, George R. A contribution to the etnography of the Karaja indians of Central Brazil. Virginia : Univ. Microfilms International, 1982. 348 p. (Tese de Doutorado)

- EHRENREICH, Paul. Contribuições para a etnologia do Brasil. Rev. do Museu Paulista, São Paulo : Museu Paulista, v. 2, n.s., p. 7-135, 1948.

- FONSECA, José Pinto. Da cópia da carta que o alferes José Pinto da Fonseca escreveu ao Exm. General de Goiás, dando-lhe conta do descobrimento de duas nações de índios, dirigida do sítio onde portou. Rev. do Instituto Histórico e Geográfico Brasileiro, Rio de Janeiro : IHGB, v. 8, 1868.

- FORTUNE, David; FORTUNE, Gretchen. Karajá literary acquisition and sociocultural effects on a rapidly changing culture. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, s.l. : s.ed., v. 8, n. 6, 1987.

- FORTUNE, Gretchen, The importance of turtle months in the Karaja world, with a focus on ethnobiology in indigenous literary education. In: POSEY, Darrell A.; OVERAL, William Leslie (Orgs.). Ethnobiology : implications and applications. Proceedings of the First International Congress of Ethnobiology (Belem, 1988). v.1. Belém : MPEG, 1990. p. 89-98.

- FUNDAÇÃO DE AMPARO E DESENVOLVIMENTO DE PESQUISA. Estudos de Impacto Ambiental : Hidrovia Tocantins-Araguaia. v. 1, Texto Principal. Belém : Fadesp, 1999.

- GIANNINI, Isabelle Vidal. Relatório ambiental de identificação e delimitação Terra Indígena Cacique Fontoura. São Paulo : s.ed., 2001. 98 p.

- KRAUSE, Fritz. Nos sertões do Brasil. Rev. do Arquivo Municipal, São Paulo : Arquivo Municipal, v. 66 a v. 91, 1940/1943.

- LEITÃO, Rosani Moreira. Educação e tradição : o significado da educação escolar para o povo Karajá de Santa Isabel do Morro, Ilha do Bananal-TO. Goiânia : UFGO, 1997. 297 p. (Dissertação de Mestrado)

- LIMA FILHO, Manuel Ferreira. Os filhos do Araguaia : reflexões etnográficas sobre o “Hetohoky” Karajá, um rito de iniciação masculina. Brasília : UnB, 1991. (Dissertação de Mestrado). Publicada com o título “Hetohoký : um rito Karajá”. Goiânia : UCG, 1995. 183 p.

- LIPKIND, William. The Carajá. In: STEWARD, J. (Ed.). Handbook of South American Indians. v. 3. Washington : Smithsonian Institution Bureau of American Ethnology, 1948.

- MELO, Juliana Gonçalves de. Um estudo sobre o contato interétnico e seu impacto nas crenças e práticas médicas Karajá. Brasília : UnB, 1999. (Monografia de Graduação)

- OLIVEIRA, Haroldo Cândido. Sobre os dentes Karajá de Santa Isabel. Rev. do Museu Paulista, São Paulo : Museu Paulista, v. 2, n.s., p. 169-74, 1948.

- PAINKOW, Aurielly Queiroz et al. Aldeias da ilha : estudos e registros da realidade social dos indígenas que habitam a Ilha do Bananal. Palmas : Univers. do Tocantins, 2002. 48 p.

- PAULA, Luiz Gouvea de. “Fala direito, Karajá!”. Rev. do Museu Antropológico, Goiânia : UFGO, v. ¾, n. 1, p. 53-64, jan./dez.1999/2000.

- PERET, João Américo. As filhas do sol e a origem do casamento : lenda Karajá. Arquivo de Anat. e Antrop., Rio de Janeiro : Inst. Antrop. Prof. S. Marques, n. 4, p. 457-61, 1980.

- PETESCH, Nathalie. La pirogue de sable modes de représentation et d’organisation d’une société du fleuve : les Karajá de l’Araguaia (Brésil central). Paris : Université Paris X, 1992. (Tese de Doutorado)

- --------. A trilogia Karajá : sua posição intermediária no continuum Jê-Tupi. In: VIVEIROS DE CASTRO, Eduardo; CUNHA, Manuela Carneiro da (Orgs.). Amazônia : etnologia e história indígena. São Paulo : USP-NHII/Fapesp, 1993. p. 365-84. (Estudos)

- PIMENTEL, Maria do Socorro. A educação na revitalização da língua e da cultura Karajá na aldeia de Buridina. Rev. do Museu Antropológico, Goiânia : UFGO, v. ¾, n. 1, p. 65-74, jan./dez. 1999/2000.

- POLECK, Lydia (Org.). Adornos e pintura corporal Karajá. Goiânia : UFGO ; Brasília : Funai, 1994. 47 p. (Textos Indígenas, Série Cultura)

- --------. Textos Karajá. Goiânia : UFGO, 1998. 51 p. (Textos Indígenas, Série Cultura)

- RAMALHO, Jair Pereira. Pesquisas antropológicas nos índios do Brasil : a cefalometria nos Kayapó e Karajá. Rio de Janeiro : Fed. das Escolas Federais Isoladas, 1971. 314 p. (Tese para Concurso Prof. Titular de Anatomia)

- --------; PAPAIS, Regina Maria. Pesquisas antropométricas em brasilíndios : o diâmetro bizigomático e altura morfológica da face nos Karajá - coeficiente de correlação. Arquivos do Instituto Benjamin Baptista, Rio de Janeiro : Instituto Benjamin Baptista, v. 15, p. 453-9, 1972.

- RAMOS, Luciana Maria de Moura. A construção da mulher na sociedade Karajá. Brasília : UnB, 1996. (Monografia de Graduação)

- RIBEIRO, Eduardo Rivail. (ATR) vowel harmony and palatalization in Karaja. Santa Bárbara Papers in Linguistics, Santa Bárbara : UCSB, v. 10, 2000.

- RODRIGUES, Patrícia de Mendonça. O povo do Meio : tempo, cosmo e gênero entre os Javaé da ilha do Bananal. Brasília : UnB, 1993. 438 p. (Dissertação de Mestrado)

- SÁ, Cristina. Observações sobre a habitação em três grupos indígenas brasileiros. In: NOVAES, Sylvia Caiuby (Org.). Habitações indígenas. São Paulo : Nobel ; Edusp, 1983. p. 103-46.

- SANTOS, Rosirene R. dos. A estética Karajá e a ótica ocidental. São Paulo : USP, 2001. (Dissertação de Mestrado)

- SILVA, Maria do Socorro Pimentel da. A função social do mito na revitalização cultural da língua Karajá. São Paulo : PUC, 2001. 242 p. (Tese de Doutorado)

- --------. A situação sociolingüística dos Karajá de Santa Isabel do Morro e Fontoura. Brasília : Funai/Dedoc, 2001. 143 p. Originalmente Dissertação de Mestrado/UFGO.

- SIMÕES, Mário Ferreira. Cerâmica Karajá e outras notas etnográficas. Goiânia : UCG-IGPHA, 1992.

- TAVEIRA, Edna Luisa de Melo. Etnografia da cesta Karaja. São Paulo : USP, 1978. (Dissertação de Mestrado). Publicada com o mesmo título em 1982 pela UFGO.

- TAVENER, Christopher J. The Karajá and the Brazilian frontier. In: GROSS, Daniel R. (Ed.). Peoples and cultures of native South America : an anthropological reader. New York : The American Museum of Natural Story, 1973. p. 433-62.

- TORAL, André Amaral de. Cosmologia e sociedade Karajá. Rio de Janeiro : UFRJ-Museu Nacional, 1992. 414 p. (Dissertação de Mestrado)

- --------. Estudo de Impacto Ambiental - Hidrovia Araguaia-Tocantins : diagnóstico ambiental Karajá. São Paulo : s.ed., 1997. 127 p.

- --------. Laudo pericial antropológico relativo à Ação Ordinária de nº 91.0004263-3 (I-1.363/91) de desapropriação indireta na 4ª Vara da Justiça Federal do Mato Grosso. s.l. : s.ed., 1992. 120 p.

- TSUPAL, Nancy Antunes. Educação indígena bilingue, particularmente entre Karajá e Xavante : alguns aspectos pedagógicos, considerações e sugestões. Brasília : UnB, 1979. 157 p. (Dissertação de Mestrado)

- VIANA, Adriana M. S. A expressão do atributo na língua karajá. Brasília : UnB, 1995. 89 p. (Dissertação de Mestrado)

- Tigrero : the film that was never made. Dir.: Mika Kaurismaki. Filme Cor, 35 mm, 1994.