Jamamadi

- Self-denomination

- Where they are How many

- Linguistic family

The Jamamadi are among the little known indigenous peoples of the region of the Juruá and Purús rivers who survived the two rubber booms in the mid-19th Century. In the 1960s, it was predicted that they would disappear as a differentiated group, but from that time on, the Jamamadi have succeeded in recovering, both in demographic and in cultural terms. This entry presents the scattered information that we have available about this group.

Name

There are controversies with regard to the self-denomination and cultural identity of the Jamamadi. There are authors who say that there aren’t any linguistic and cultural differences between the Jamamadi, Kanamanti and Jarawara, while others affirm that the Jamamadi are divided into three subgroups: Kanamanti, Jarawara and Banawa-Yafi.

The question of self-denomination remains open. The Jamamadi of the Jarawara/Jamamadi/Kanamanti Indigenous Land are recognized by this name in contacts with non-Indians or with members of other ethnic groups, but the anthropologist Lúcia Helena Rangel argues that the term jamamadi was attributed to these people probably by the Paumari Indians and means “people of the forest". The American ethnologist Steere, at the beginning of the 20th Century, also explained the term through its origin from the Paumari. According to him, jiwã-mãgi means "wild (or) savage man". In the Paumari language, jama means "forest" and makhari, "man".

The missionary Rick Reece is the only author who has affirmed that the common self-denomination of the Jamamadi and Banawá-Yafi was kitiya. Rangel, however, has called attention to the fact that various groups of the Arawá language family, such as the Jamamadi, Kulina and Deni, share in common principles of social organization into small units which are, ideally, endogamic and politically autonomous. These units are designated by the suffixes -deni or -madiha. Among the Jamamadi, the self-denominations of the present-day units would be: Anopideni ("people of the little bird"), Aptorideni ("people of the jaguar"), Havadeni, Iuaseredeni, Makoideni, Sirorideni, Sivakoedeni ("people of the bamboo"), Tamakorideni, Tanodeni ("people of the japu bird"), Zoazoadeni e Zomahimadi. In view of this situation it would not be surprising if future researches revealed that Jamamadi is only an externally imposed term of reference, but accepted by various local groups as a form of identification.

In relation to the Kanamanti, despite the fact that official documents and several anthropological texts recognize them as an indigenous people, Kanamanti is the self-denomination of the Jamamadi groups that used to inhabit the villages of the region of the Saburrum stream and which presently live together with other Jamamadi groups of the Jarawara/Jamamadi/Kanamanti Indigenous Land. The Jarawara call the Kanamanti, Wahati.

Language

The Jamamadi language belongs to the small Arawá family of Western Amazônia. It has been studied in detail by the American missionaries Barbara and Robert Campbell, of the SIL (International Linguistics Society, formerly the Summer Institute of Linguistics), who have done pioneering work since 1963, developing a simple and clear spelling for the language. According to their information, the language most similar to Jamamadi is Jarawara. Most Jamamadi are monolingual, such that few speak Portuguese well.

Location

The present territory of the Jamamadi includes lands in the region of the middle Purus, in the states of Amazonas and Acre; in the regions of the Curiá and Saburrun (Sabuhã) streams, tributaries of the Piranhas River; and on the Mamoriazinho, Capana, Santana and Teruini streams, tributaries of the Purus. The Jamamadi are known for the fact they inhabit the terra firme forests as well as the dense ombrophylous forests of the low plateaus.

The five actual indigenous areas, all homologated, are:

| Indigenous Lands | Municipality | Siza (ha) |

| Caititu | Labrea | 306.062 |

| Camadeni | Pauini | 150.930 |

| Igarapé Capanã | Boca do Acre | 122.556 |

| Inauini/Teuini | Boca do Acre/Pauini | 468.996 |

| Jarawara/Jamamadi/Kanamanti | Labrea/Tapauá | 390.233 |

All of these lands are included in the PPTAL demarcation project (Integrated Project for Protection to the Indigenous Populations and Lands of Legal Amazônia), in the sphere of action of the Pilot Program for the Protection of the Tropical Forests in Brazil (PPG7).

The Jamamadi are the only inhabitants of two Indigenous Lands (the Capana stream and Inauini/Teunini), while in the others space is divided with the Apurinã and Paumari (Caititu), or with the Jarawara (Jarawara/Jamamadi/Kanamanti).

Demography

The information on the present population of the Jamamadi is approximate. A crossing of the data from Funai, the PPTAL and our fieldnotes allows us to present an estimate of 800 individuals (in 2000).

In relation to the birth and death rates, for example, we only have statistics from the communities of the Jarawara/Jamamadi/Kanamanti Indigenous Land. The author of this entry has recorded average annual birth rates of 3.3% for the period from 1996 to 2000. In a census undertaken by the missionary Robert Campbell, of SIL, in the year 2000, individuals in the age brackets from 0 to 19 represent 59.9% of the population.

Interethnic marriages seem to be very rare. There is only information on several marriages with Jarawara and Banawa-Yafi. And there is still no information recorded on Jamamadi individuals who live in urban settings.

History of contact

The traditional territory of the Jamamadi was the region between the Juruá and Purus rivers, with the natural borders of the Mamoriazinho, the Pauini and the right bank of the Xiruã. The British traveller William Chandless located them in the 19th Century on the left side of the Purus, extending nearly 300 miles between the Sepatini and "Hyuacu" rivers. The German ethnologist Paul Ehrenreich also located Jamamadi territory, in the second half of the 19th Century, on the left side of the Purus, from the mouth of the Ituxi to above the Pauini.

The first mention of the Jamamadi in an historical source was made in 1845, by the military officer João Henrique Matos, who makes a reference to "many malocas". At that time, some Jamamadi were already working in manual labor for the merchant Manoel Urbano da Encarnação, who controlled the exploitation of "drogas do sertão" [backland drugs, i.e., spices, herbs, etc] on the middle Purus. The French naturalist Castelnau also saw "Jamaris" in 1847.

In 1852, the expedition of Serafim da Silva Salgado met 400 Jamamadi at the mouth of the Macuiany stream and more than 100 at the mouth of the Euacá stream. Manoel Urbano da Encarnação found two more malocas during his 1861 expedition and described the Jamamadi as neighbors of the Apurinã, being numerous and quite inclined to work in the fields and hunting.

The objective of the missionary efforts of the Italian Franciscans Venâncio Zilocchi and Matteo Canioni, in 1877, was primarily to attract Jamamadi groups to the mission of Imaculada Conceição on the Purus River, situated on the left bank of the Mamoriazinho stream. The friars found eight abandoned malocas, the dwellers of which had fled to the headwaters of the Cainahã River because of the death of two women, caused by an Apurinã. Canioni finally succeeded in attracting 50 Jamamadi, but these did not want to stay in the mission for fear of the Apurinã and because of the lack of food. In a later attempt, the friars initially succeeded in convincing another group whom they met going up the Mamoriazinho, to descend to the mission, but these Jamamadi went back to their maloca after receiving clothes and tools, discouraging the missionaries from continuing their work.

Chandless wrote in 1866 that the Jamamadi lived exclusively on terra firme and the streams, avoiding the Purus, and that they did not have canoes, which could be interpreted as evidence that they had been a people of the terra firme for a long time. The rubber boss Labre, founder of the city of Lábrea, also described them in 1872, as living on the terra firme. According to this author, they were agriculturalists and did not have commerce with other people, being timid and fleeing from contact with the Whites.

Despite their attempts to keep their distance from the Whites, the Jamamadi were not spared from the vicissitudes of the times and several groups were transformed into rubber-gatherers or suppliers of agricultural products, either by their gradual integration into the patron-client system or by using various forms of direct violence.

At the end of the 19th Century, the American ethnologist Joseph Steere encountered Jamamadi groups at the headwaters of the Mamoriazinho, after passing through areas of deserted plantations. In one large abandoned maloca, he learned that, shortly before he arrived, the 130 dwellers had been struck by a measles epidemic introduced by an Indian and which had caused the deaths of nearly 100 Indians.

After his visit to the region in 1904 and 1904, Euclides da Cunha reported that, on the Inauini River, he encountered a camp of Peruvian rubber-gatherers who held 60 Jamamadi in their service. The Jamamadi were held prisoner in a circle formed by men armed with rifles to avoid any attempt at escape. They had been taken prisoner in their maloca many leagues from there and led to therubber camp by all sorts of violent means. Several died on the journey, others upon arriving at the camp.

In the beginning of the 20th Century, the Jamamadi were nearly extinct. The Manauacá Indian Post of the SPI (Indian Protection Service), on the Teunini River, was created to protect the Jamamadi. In the 1930s, about 85 Jamamadi lived on the post, gathering latex and Brazil-nuts. In 1943, the post was transferred to another location, but only 28 Jamamadi stayed there, until the post was closed in 1945.

In an inspection trip, Dorval de Magalhães visited indigenous groups on the Duque stream, tributary of the Mamoriá River, where he encountered 22 Indians, of which the women were Jamamadi and the men Apurinã, who were exploited by the merchant Manoel Bezerra de Araújo. Magalhães also recorded the presence of Jamamadi groups on the Piranha River and the Curiá stream.

From the 1940s to 1960s, the Jamamadi, like other peoples of the region, were victims of extermination expeditions, specifically on the Pauini River.

A basic survey of ancient and present settlements in the Jarawara / Jamamadi / Kanamanti Indigenous Land undertaken by the author at the end of 2000, allows us to make a preliminary evaluation of Jamamadi migrations over the last 60 to 80 years. The regions formerly inhabited were the Curiá, Curiazinho and Saburrum streams and, outside the limits of the present Indigenous Land, the Apahá and Aripuanã streams and the Piranha river. Over several decades, the communities moved further and further to the south, but always maintaining their distance from the Purus. In this context, the village of São Francisco, with the SIL mission, has represented since the end of the 1960s a kind of “blockade village" for the migrations due to its great attraction.

A very important historical moment about which the Jamamadi speak a great deal was a series of epidemics that broke out in the middle of the 20th Century and which, as a result of their impacts, seems to have been responsible for several migrations. When Robert and Barbara Campbell arrived in that region in 1963, they found the Jamamadi population of that land reduced to around 80 people, including few children, in desolate conditions. From that time on, this situation could be completely reverted. The present population is around 240 individuals.

As far as present day interethnic relations, it is possible to verify that the Jamamadi continue avoiding contact with the Whites, called jara. Their relations with the Paumari are friendly unlike with the Jarawara, with whom their relations are at times tense.

Economic activities

The annual cycle is marked by the rains, with higher precipitation levels from November to February, and by the water levels, which are generally highest in March and April and lowest from July to October.

The Jamamadi are mainly agriculturalists and terra firme hunters. The two most cultivated plants are manioc and sweet cassava, of which they know at least 17 and 8 varieties, respectively. In the past, the importance of sweet cassava was greater than it is today, such that they used to make beiju from sweet cassava. Presently, manioc flour is the basis of their diet. One type of food which is highly appreciated is “manioc flour bread" (yawa), made from mashed manioc, kept in baskets lined with banana tree leaves and later cooked in a pot.

It is interesting to observe that the Jamamadi do not practice weeding and, instead, they put more time into managing the capoeiras [shrubbery] that are formed whether by the planting of fruit trees, or by the intense hunting of small and medium-sized animals. As gardens are totally overrun by weeds after a year, the Jamamadi have to open up new areas annually, but this does not mean a loss in agricultural importance of the areas after more than a year of succession , because the tubers are usually taken out of the ground up to three years later.

Around the villages one can observe a mosaic of ciliary forests, gardens and shrubbery in various stages of succession, which provide the Jamamadi with a series of cultivated and wild plants, as well as game animals. This is of great importance. In several villages, the large number of forest animals in captivity is remarkable. There are two modes of hunting: (1) "hunting nearby", which is associated with the shrubbery and the surrounding environment of the villages, and (2) "long distance hunting", associated with the seasonal settlements for copaíba extraction.

Fishing is merely a supplementary activity for the Jamamadi. They fish with bow and arrow, hook and line or harpoons, but they also use a plant which they call kona and which is known in the region as tingui. This fish poison is extracted from the root of the kona plant by beating it until it becomes soft. Normally it is used in the dry season, above all on the occasion of festivals and assemblies. In the past, the Jamamadi used fish-spears and traps more often.

The Jamamadi gather forest fruits and honey and prepare various non-alcoholic drinks from the fruits of the açaí, bacaba and pupunha.

The principal products that are commercialized are extractivist and agricultural, besides a bit of artwork. Among the regional extractivist products, presently the Jamamadi commercialize mainly copaíba oil, gathered from the seasonal settlements called centers.

Groups of five to ten men are formed to go to the centers. Each man has his own trail. The sum total of the trails defines the area of exploitation of each center, and the time they stay is determined by the time necessary to fill the gallon containers with oil, which can vary from 15 to 25 days.

In the centers there are no gardens or fruit trees. Thus the men usually take manioc flour produced in the villages and hunt in these locales. Meanwhile, in the villages, during the men’s absence, the women not only make hammocks and baskets, but also fish or, occasionally, hunt small and medium-sized game animals.

The extraction of copaíba oil is tiring, arduous and time-consuming work, and is hardly worth the effort given that the forms of trade practiced by the river merchants to acquire the oil are scandalous. These merchants generally trade these products for merchandise, since few Jamamadi have concrete ideas about the value of money. Thus, some merchants are able to get profit margins of up to 3,000% or more, according to our calculations.

The practice of cutting down the trunks to extract the oil has reduced the quantity of trees considerably in various parts of the Indigenous Lands. It is for that reason that the Jamamadi of the region of the middle Purus at present do not extract more than sorb, another forest product, since it has become very difficult to find their trees on terra firme.

In any case, although the demographic density of the lands of the Jamamadi may be very low (from 0.03 to 0.1 inhabitants/km², depending on the land), they use their space in an efficient way, because of the system of centers with radiating trails, given that the centers have a very wide spatial distribution.

Social and political organization

The local groups are generally very small. A village with more than 100 inhabitants is uncommon. Descent is traced through the paternal line (patrilineality). As for matrimonial alliances, traditionally preference is given to marriages with cross-cousins (father’s sister’s children and mother’s brother’s children). This basic pattern has been conserved until today, but the exceptions to this rule are multiplying in several communities, perhaps due to missionary influence.

The post-marital residence rule is to live with the wife’s family (uxorilocality), combined with the son-in-law’s obligation to render services to his wife’s father. After the birth of the first child, there is the possibility of opting for a new residence. There still exists a traditional rule according to which the first child is reared by the maternal grandmother, while the children born after are reared by the paternal grandmother.

Marriages are quite stable in general. The divorce rate was already very low before the arrival of the missionaries, but extramarital sexual behavior, which used to be very liberal, has suffered changes.

Personal names continue to be indigenous, but, at the same time, Christian-Portuguese names are used for official records.

Material culture

Jamamadi houses are exactly like those of the riverine population: built on stilts, with wooden floorboards made from paxiúba palm and covered by canaraí thatch. Inside the houses, each family has its own place to sleep. The young single women sleep protected by the family mosquito net, while each of the young men has his own net.

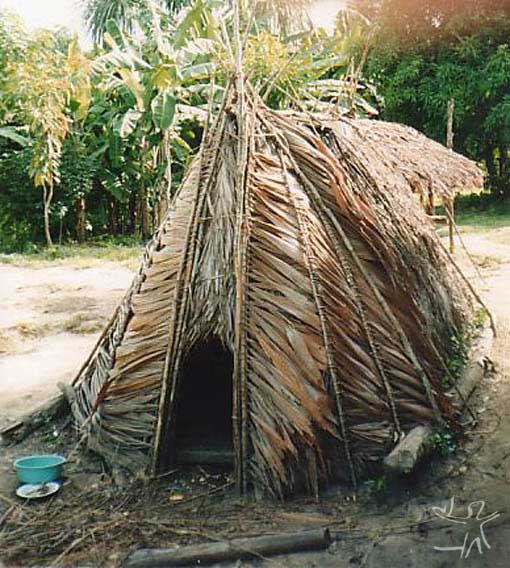

In the past, the dwelling-places were large conical- shaped malocas, and were some of the largest ever seen. According to Steere, they had diameters of up to 40 meters and heights of up to 22 meters. They were subdivided into up to 25 family compartments.

To the side of the houses, small seclusion huts (wawasa) were built, in the form of malocas, for girls after their first menstruation.

The Jamamadi also build small huts or shelters for seasonal migrations or hunting and gathering expeditions.

They sleep in hammocks made of cotton or the bark of young chestnut trees. This bark is beaten, and later washed and dried to take out the fine threads, that are then rolled and twisted by the hand, over the thigh, until they form string which is then rolled into a cylindrical-shaped ball.

Of the objects of domestic use, the old reports mention ceramic utensils without any ornamentation or painting and manioc-squeezers.

The current attire consists of clothes acquired from the Whites or sewn from their cloths. In the past, the men used only a cord to tie up the penis, at times covered by various strings hung from the cord, and the women, cotton aprons.

Current female adornments include: headdresses made of macaw and toucan feathers, glued with resin; various types of collars made of seeds or monkey teeth; bracelets made of riverine shells, tied together with cotton string.

Their boats are small canoes, carved out of a single piece of wood. In the past, they were made of jutaí bark and were about 5 meters long and one meter wide.

Among their weapons, the bows are up to two meters in length and are made of palmwood. The part in the middle is thicker than the extremities. The inner surface is flat and the outer, convex. The string is made of palm fibres. The arrows are up to 1.7 meters in length. The shaft of 1.5 meters is made of taquara bamboo. Some small feathers are stuck only on the lower extremity. The tip, from 15 to 18 centimeters in length, is made of pieces of paxiúba. Sometimes, it is sharpened in a triangular form, with cotia or paca [rodent] teeth, and cut with shallow notches. The tip is entirely covered by a layer of poison. Because of the notches, the tip breaks in the wound of the game animal hit. In the past, the Jamamadi also used blowguns.

Religion, mythology and rituals

There are almost no reports on Jamamadi religion and mythology. Rangel, however, dedicated a part of her thesis to theories of Jamamadi shamanism, interpreting it as responsible for the fission of communities. Our knowledge of Jamamadi rituals and festivals is very fragmentary. One of the most important festivals seems to be female initiation, that is, a series of rituals that mark the transition of girls to the status of adult women.

What can easily be observed however, is the esteem that snuff (sina) has in daily life. It is made of green tobacco leaves, which are toasted, dried and pounded inside Brazil-nut burs. A portion of cacau ash is added to the powder. The snuff is consumed on various occasions.

The Jamamadi practice the "ritual of chinã" (this is a Portuguese version of the indigenous term sina, which means snuff), in which all families participate. The owner of the house puts a portion of sina on a green leaf and holds it in the palm of his hand, then it is passed from one person to the next, a hawk legbone being used for inhalation. The orifice of the bone is smoothened with wax to facilitate adapting it to the nostril. After, the inside of the bone is cleaned with a feather.

Note on the sources

The only ethnographic monograph on the Jamamadi is the doctoral thesis by Lúcia Helena Vitalli Rangel, Os Jamamadi e as armadilhas do tempo histórico [The Jamamadi and the traps of historical time], defended in 1994 at the Catholic Pontifical University of São Paulo. Other ethnographic sources include the reports by the explorer William Chandless, the ethnologists Paul Ehrenreich and Joseph Steere, in the beginning of the 20th Century and, more recently, by Gunter Kroemer (of CIMI-Lábrea).

The language of the Jamamadi was studied principally by the missionaries Barbara and Robert Campbell, but there is still much material which awaits publication.

Sources of information

- AYRES, Sandra A. Viagem de supervisão a terras indígenas na Amazônia Legal demarcadas pelo PPTAL : um relato. In: KASBURG, Carola; GRAMKOW, Márcia Maria (Orgs.). Demarcando terras indígenas : experiências e desafios de um projeto de parceria. Brasília : Funai/PPTAL/GTZ, 1999. p.167-96.

- CAMPBELL, Barbara. Hiyama. Porto Velho : Funai/SIL, 1991. 42 p. (Cartilha Jamamadí, 4 e 5). Circulação restrita.

- --------. Jamamadi discourse. Notes on Linguistics, s.l. : s.ed., v.2, 1977.

- --------. Jamamadi noun phrases. In: FORTUNE, David L. (Ed.). Porto Velho work-papers. Brasília : SIL, 1985. p. 130-65.

- --------. Repetition in Jamamadi discourse. In: GRIMES, Joseph E. (Ed.). Sentence initial devices. Dallas : SIL ; Arlington : University of Texas, 1986. p. 171-85 (SIL Publications in Linguistics, 75)

- --------. Repetição no discurso Jamamadi. Lingüística, s.l. : s.ed., v.9, n.1, p. 129-56, 1987.

- --------; CAMPBELL, Robert Lewis (Comps.). Yama abe - Insetos. Porto Velho : SIL, 1993. 49 p. (Cartilha Jamamadí, 6). Circulação restrita.

- CAMPBELL, Robert Lewis. Jamamadi verification suffixes. Notes on Linguistics, sl. : s.ed., v. 2, 1977.

- --------. Marcadores de fonte de informação na língua Jamamadí. Lingüística, s.l. : s.ed., v.7, p. 117-25, 1977.

- --------. Avaliação dentro das citações na língua Jamamadí. Lingüística, s.l. : s.ed., v.9, n.2, p.9-30, 1988.

- --------; CAMPBELL, Barbara. Preliminary observations concerning the rarity of exact repetition in Jamamadi. Notes on Linguistics, sl. : s.ed., v.19, p. 10-20, 1981.

- DERBYSHIRE, Desmond C. Arawakan (Brazil) morphosyntax. Work Papers of the SIL, s.l. : Univ. of North Dakota, v.26, p. 1-81, 1982.

- EHRENREICH, Paul. Beiträge zur Völkerkunde Brasiliens. Veröffentlichungen aus dem Königlichen Museum für Völkerkunde, s.l. : Museum für Völkerkunde, v.2, p. 1-80, 1891.

- --------. Materialien zur Sprachenkunde Brasiliens : vokabulare von Purus-Stämmen. Zeitschrift für Ethnologie, s.l. : s.ed., v.29, p. 59-71, 1897.

- --------. Contribuições para a etnologia do Brasil, parte 2 : sobre alguns povos do Purus. Rev. do Museu Paulista, São Paulo : Museu Paulista, n.s., v.2, p.17-135, 1948 [1891].

- ENCARNAÇÃO, Manoel Urbano da. Carta sobre costumes e crenças dos índios do Purús, dirigida a D. S. Ferreira Penna. Boletim do Museu Paraense de História Natural e Ethnographia, Belém : Museu Paraense de História Natural e Ethnographia, v.3, n.1, p. 94-7, 1900.

- FÉLIX, Rita de Cássia. Relatório de delimitação da Área Indígena Jarawara/ Jamamadi/ Kanamati. Brasília : Funai, 1987. 36 p.

- FUNDAÇÃO DE CULTURA E COMUNICAÇÃO ELIAS MANSOUR; CIMI. Povos do Acre : história indígena da Amazônia Ocidental. Rio Branco : Cimi/FEM, 2002. 58 p.

- ÍNDIOS : isolados em risco e escravidão por dívida. 1995.

- KROEMER, Gunter. Caxiuara : o Purús dos indígenas. Ensaio etno-histórico e etnográfico sobre os índios do Médio Purús. São Paulo : Loyola, 1985. (Missão Aberta, 10)

- METRAUX, Alfred. Tribes of the Jurua-Purus Basins. In: STEWARD, Julian H. (Ed.). Handbook of South American Indians. v.3. Washington : Smithsonian Institution, 1948. p.657-86. (Bureau fo American Ethnology Bulletin, 43)

- NOGUEIRA, Ana Luiza Estellita Lins. Jamamadi. In: GONÇALVES, Marco Antônio Teixeira (Org.). Acre : história e etnologia. Rio de Janeiro : Núcleo de Etnologia Indígena/UFRJ, 1991. p. 183-200.

- PRANCE, Ghillian T. The poisons and narcotics of the Dení, Paumari, Jamamadí and Jarawara indians of the Purus river region. Rev. Brasileira de Botânica, s.l. : s.ed., v.1, p. 71-82, 1978.

- RANGEL, Lúcia Helena Vitalli. Os Jamamadi e as armadilhas do tempo histórico. São Paulo : PUC-SP, 1994. (Tese de Doutorado)

- RIVET, Paul; TASTEVIN, Constant. Les langues du Purús, du Juruá et des régions limitrophes : 1. Le groupe arawak pré-andin. Anthropos, s.l. : s.ed., v. 14/15, p. 857-90, 1919/1920 ; v.16/17, p. 298-325 e 819-28, 1921/1922 ; v.18/19, p. 104-13, 1923/1924.

- --------. Les tribus indiennes des bassins du Purús, du Juruá et des régions limitrophes. La Géographie, s.l. : s.ed., v.35, p. 449-82, 1921.

- --------. Les langues arawak du Purús et du Juruá (groupe arauá). Journal de la Société des Américanistes, Paris : Société des Américanistes, n.s., v.30, p. 71-114 e 235-88, 1938.

- SCHRÖDER, Peter. Levantamento etnoecológico : experiências na região do Médio Purus. In: GRAMKOW, Márcia Maria (Org.). Demarcando terras indígenas II : experiências e desafios de um projeto de parceria. Brasília : Funai/PPTAL/GTZ, 2002. p. 223-39.

- --------; COSTA JÚNIOR, Plácido. Levantamento etnoecológico do complexo Médio Purús II. Fortaleza/Cuiabá : s.ed., s.d.. 246 p. (Relatório para o PPTAL, mimeo)

- STEERE, Joseph Beal. Narrative of a visit to indian tribes of the Purus river, Brazil. Annual Report of the Smithsonian Institution, Washington : Smithsonian Institution, p. 359-93, s.d.

- --------. Tribos do Purus. Sociologia, s.l. : s.ed., v. 9, p. 64-78 e 212-22, 1949.