Huni Kuin (Kaxinawá)

- Self-denomination

- Huni Kuin

- Where they are How many

- AC 11729 (Siasi/Sesai, 2020)

- Peru 2419 (INEI, 2007)

- Linguistic family

- Pano

“The shaman gives and takes life. To become a shaman, you go alone into the forest and wrap your entire body in embira. You lie down at a path intersection with your arms and legs outstretched. First come the night butterflies, the husu, who completely cover your body. Next comes the yuxin who eats the husu until reaching your head. Then you grab him tightly. He transforms into a murmuru palm, which is covered in spines. If you’re strong enough and don’t let go, the murmuru transforms into a snake, which wraps around your body. If you keep hold, he transforms into a jaguar. You continue holding him. And this continues until finally you’re left holding nothing. You’ve won the ordeal and you can speak: you explain that you want to receive muka and he gives it to you”. [Siã Osair Sales]]

Identification

The Kaxinawá belong to the Pano linguistic family that inhabits the tropical forest of eastern Peru, from the Andean foothills to the border with Brazil, and western Brazil in the states of Acre and southern Amazonas, covering the areas of the Upper Juruá and Purus and the Javari Valley, respectively.

The Pano groups designated as nawa form a subgroup of this family due to the close proximity of their languages and cultures and to their geographical proximity over a long period of time. Each group calls itself huni kuin, ‘true humans’, or people with known customs. One of the characteristics distinguishing the huni kuin from other humans is the name transmission system. This system exists among the Kaxinawá and the Sharanawa, Mastanawa, Yaminawa and other nawa.

The first reports from travellers in the region contain a confusing mix of indigenous group names that persists even today. This stems from the fact that the names do not reflect a consensus between namer and named. The Pano namer calls (almost) all the others nawa, and himself and his kin huni kuin. Thus the Kulina were called pisinawa (‘those who stink’) by the Kaxinawá, while the Paranawa called the Kaxinawá themselves pisinawa. The name Kaxinawá itself seems to have originated from an insult. Kaxi means bat, or cannibal, but may also mean people who walk about at night.

Today the Kaxinawá call all these related groups ‘Yaminawa’; both those who maintain regular contact with the whites, and the Pano groups who live in the headwaters of the Upper Juruá and Purus rivers and remain hidden in the recesses of the forest, avoiding ‘peaceful’ contact with national society.

Location

The Kaxinawá live on the Brazilian-Peruvian border in Western Amazonia. The Kaxinawá villages in Peru are located on the Purus and Curanja rivers. The villages in Brazil (in the state of Acre) are spread along the Tarauacá, Jordão, Breu, Muru, Envira, Humaitá and Purus rivers.

I conducted fieldwork in the Cana Recreio, Moema and Nova Aliança villages on the Purus river, near to the border with Peru. The Peruvian and Brazilian Kaxinawá were separated at the beginning of the 20th century when a group that had been gathered at a seringal (rubber extraction area) on the Envira river relocated to the headwaters of the Purus river, in Peruvian territory, after a revolt against the rubber boss (McCallum, 1989a: 57-58; Aquino, 1977; Montag, 1998). The groups coming from Peru converged with the Brazilian Kaxinawá through marriage, though even today differences in the lifestyle of the two groups can be observed.

Some Kaxinawá groups migrated from the Envira river, where they had been engaged in rubber extraction work, to the Purus. Most of these Envira Kaxinawá settled in Fronteira village and in various nearby settlements. Over the last two decades, the migratory movement has continued with other Kaxinawá arriving from Peru and from the Envira and Jordão rivers settling in villages along the Purus.

In the Alto Purus Indigenous Territory, the Kaxinawá also live alongside their traditional neighbours, the Kulina, for whom this reserve was originally created.

History

The first travellers’ reports in the Upper Juruá region to speak of the Kaxinawá identify the Muru, Humaitá and principally the Iboiçu rivers – three affluents of the Envira (itself an affluent of the Juruá) – as the ‘original’ habitat of the Kaxinawá prior to the arrival of the rubber-tappers. While the Kaxinawá occupied the right shore of these rivers, the left shore was occupied by the Kulina (McCallum, 1989; Tocantins, 1979). As early as the 18th century, colonizers were apparently organizing slave raiding expeditions in the region, though no record of these initial violent encounters is available. These first incursions were undoubtedly sporadic and short-term.

At the end of the 19th century – from 1890 onwards – a wave of invasions by Peruvian caucheiros (caucho rubber extractors) began and lasted for about twenty years. Extracting caucho rubber requires the trees to be cut down, meaning that the region was quickly exhausted. Rubber, Hevea brasiliensis, is harvested by cutting the tree periodically to preserve it. As a result, the Brazilian rubber-tappers stayed in the region much longer, despite the ups and downs of the rubber commodity market.

During this period of violent contact, the local indigenous groups were attacked by the explorers, who among other things brought new diseases. In 1913 the Juruá region had 40,000 migrants (most of them coming from the northeastern state of Ceará), and the Purus 60,000. The violence was organized. The job of the mateiros was not only to clear the rubber trails, they were also employed to clear the area of ‘wild’ Indians. The Kaxinawá response was to attack and raid the intruders, though some groups allowed themselves to be ‘tamed’ by the rubber bosses. This happened to the Kaxinawá group from Iboiçu, who agreed to work for Felizardo Cerqueira in exchange for industrial goods. Felizardo moved them from the Iboiçu river to the upper Envira and from there, in 1919, to the Tarauacá, where they were used in the massacre of the Papavó (McCallum, 1989). In 1924 they reached the Jordão river, where they still live today long after the death of the rubber boss. Older Kaxinawá people from this river are still branded with the initials FC (Felizardo Cerqueira), the name of their former boss.

Until 1946, the Peruvian Kaxinawá remained deep in the forest, far from the rivers navigated by traders. They preferred independence and isolation to dependence, though the latter provided ready access to guns and metal tools. They obtained some items through the Yaminawa, but it seems that in the mid 1940s they decided that they needed more and sent a team of six men to the Taraya river to negotiate directly.

As time passed, the Kaxinawá took the decision to enter into contact ‘civilization’, a decision with profound consequences, one now questioned by the Kaxinawá themselves.

Contact may be inevitable over the long-term. In the short-term, however, it depends on the initiative of the group, which had chosen an opposite strategy in the previous generation. Even today there are some ethnic groups in the region, speaking Pano and Arawak languages, who avoid any kind of contact with non-indigenous society.

In 1946, when a Brazilian trader visited the huni kuin, they knew what they wanted from him: industrialized goods, metal axes, shotguns, etc. The trader took timber and caucho rubber in exchange, but also took young people to work for him, something that had not been foreseen (Kensinger, 1975: 10-11).

Then in 1951, the German travellers Schultz and Chiara arrived: “In all we encountered eight villages, with populations varying between twenty and 120 inhabitants. We calculated the total number of Kaxinawá individuals to be between 450 and 500” (Schultz, 1955). As a result of this visit, from 75 to 80% of the adult population died in a measles epidemic. The Kaxinawá, however, identified the team’s filming of them as the cause behind the spate of deaths: according to Deshayes and Keifenheim (1982), the Kaxinawá, who tried to find an explanation for the tragedy at that time, believed that the film shrunk the person’s image and thus, with his or her yuxin yuda diminished, the person died.

The survivors fled to the Envira and Jordão rivers in Brazil where their kin were working hard for the rubber bosses. But by the following dry season, most of the refugees had decided to return to the Curanja, where there was no rubber nor bosses.

Balta, the largest Kaxinawá community in Peru, was originally created by the SIL (Summer Institute of Linguistics). Following the arrival of the missionaries, an airstrip was built to enable the transportation of goods from Pucallpa and a radio transceiver installed to provide contact with the SIL base in Yarinacocha. At the start of the 1970s, Balta had attracted so many Kaxinawá that their number reached 800 people.

The second largest Kaxinawá village in Peru, Conta, was built on the Purus river close to Puerto Esperanza, in 1968, by Kaxinawá coming from the Envira. In 1985 Conta had surpassed Balta in number of inhabitants, essentially thanks to the migration of Kaxinawá from Balta and Santarém, a village further upriver to Balta, who had left the Curanja river in search of new routes to obtain the products that thus far had been provided by the missionaries.

Conta had commercial ties with Puerto Esperanza, a small port built close to a military border post. Some Kaxinawá from Conta have engaged in military service at this port, a radical and in some cases traumatic experience.

The two Kaxinawá villages where I conducted my fieldwork, Cana Recreio and Moema, on the upper Purus, represent the convergence of the Peruvian and the Brazilian Kaxinawá traditions that developed over the previous century. The former, which maintained its autonomy for longer and has seen its village life interrupted for less time, is considered more ‘traditional’ (culturally more indigenous), despite being influenced by missionaries and contact with the Peruvian military. The latter lived for years in more disperse form and became familiarized with rubber-tapper culture by working for the rubber bosses over the space of two generations, although today it is engaged in a profound process of recovering its ‘traditions’.

The life histories of Kaxinawá people from Cana Recreio and Moema tell of the long journey between the Envira and Jordão rivers in Brazil and the Upper Purus and the Curanja in Peru until coming to a halt at Cana Recreio, on the Brazilian side of the Purus.

In April 1989 a third of the population of Cana Recreio founded a new village: Moema. During my stay in the this village there were seven houses.

Fronteira is the third Kaxinawá community in the indigenous area of the Upper Purus. The oldest village on the Brazilian side of the Purus river, it was founded by the rubber-tapper Kaxinawá of the Envira river. The leader of this village, Mário Domingos, moved from the Vista Alegre seringal, on the Envira, to the Triunfo seringal, on the Upper Purus at the start of the 1970s, at the request of the owner of the latter seringal, Chico Raulino.

The Funai post was installed at Fronteira along with an airstrip, today fallen into disuse, a school, a health post, a radio communicating with the Funai regional administration in Rio Branco and a house for the head of the post, which ended up being used by the family of the Kaxinawá leader, Mário.

In 1978 Cimi’s volunteers convinced a group of 32 people in Santa Rosa, on the border with Brazil – who had left Balta the previous year and travelled down the Curanja and Purus rivers – to live at the Funai Post on the border. This group was led by Francisco Lopes da Silva, or Pancho, who two years later founded Canoa Recreio village, an hour and a half downriver from Fronteira.

Development of the village at Fronteira is an ongoing process. Families seem to be more eager to retain their independence from each other than in the Moema and Cana Recreio villages. The houses are spaced slightly further away from each other with around a dozen cattle grazing between the houses, and the families maintain a relatively independent economy. For example, individuals barter with the traders who ply the river and supply market goods in exchange for rubber, cattle hides and chickens. While these transactions are usually controlled in the other Purus villages by the group and its leaders, during my period of research the leader of the Fronteira village showed no intention of controlling these transactions and there was no cooperative responsible for the economy of the community as a whole, as found at Cana Recreio.

A series of tasks are undertaken in conjunction, however: collective fishing trips on lakes or creeks using timbó (blackroot), the clearing of new swiddens, and hunting trips for the large festivals. One problem in terms of holding these festivals is that Fronteira lacks the song leaders needed to ‘pull’ the song.

The absence of older people with adult experience of village life (in Peru) meant that many elements of ritual, language and material culture had been forgotten. Similarly there were no men or women who knew all the katxanawa songs, the fertility rituals and txirin, the children’s initiation ritual. There were no women who knew how to weave or paint kene kuin, the Kaxinawá style of geometric design. Although this situation was a source of distinctiveness and pride for the group – which had a much more extensive knowledge of the ways of Brazilian society than its neighbours and was respected because of its powerful vine drinkers – during my last visit I saw that in Fronteira too (as in Jordão) people were looking to increase ‘the science of the ancient ones’ with the arrival of kin from Peru.

The tendency for village splits is common among the Pano and reflects the democratic base founding the community. Every family father can decide for whatever reason to move to another site and build a new community, if he has the skill to persuade others to follow him. No coercion is involved in such cases; each individual, man or woman, chooses where and with whom they live. The only constraint is affective; nobody likes to live far from their closest kin.

Shamanism

The Kaxinawá claim that the true shamans, the mukaya, those containing within themselves the bitter shamanic substance called muka, have died out, though this has not prevented them from practicing other forms of shamanism, deemed less powerful but equally effective. Only removal of the muka, equivalent to the duri among the Kulina, seems to have been exclusive to the mukaya. Other capacities, such as knowing how to communicate with the yuxin, are possessed by many adults, especially older people.

Consequently, we could say that no shamans exist and – equally – that many exist. A salient feature of Kaxinawá shamanism is the importance of discretion in relation to the person’s potential to cure or cause illnesses. The invisibility and ambiguity of this power is linked to its transitory nature. I suggest, therefore, that the claim that contemporary shamans are not as powerful as those of the past must be interpreted in light of a de-emphasizing of the figure of the shaman. Shamanism is more an event than a crystallized role or institution. This fact also derives from the strict abstinence from meat and women imposed on the mukaya shaman.

Ayahuasca consumption, considered the preserve of the shaman in many Amazonian groups, is a collective practice among the Kaxinawá, practiced by all adult men and adolescent boys who want to see ‘the world of the vine’. The mukaya is one who does not need any substance, nor any outside help to communicate with the invisible side of reality. But all adult men are a little bit shaman to the extent that they learn to control their visions and their interactions with the world of the yuxin.

Two easily observable facts that point in this direction are the frequent and public use of ayahuasca (approximately two or three times per month) and the long solitary treks undertaken by some older people without any intention of hunting or fetching medicinal plants (the usual explanation for such walks). These two activities show an active search to establish an intense contact with yuxinity.

Yuxinity is a category that aptly synthesizes the shamanic cosmovision of the Kaxinawá, a vision that does not consider the spiritual (yuxin) as something supernatural or superhuman, located beyond nature and the human. The spiritual or vital force (yuxin) permeates all the living phenomena on the earth, in the waters and in the skies.

In everyday life we see a side of reality where this universal kinship of living things remains concealed: we see bodies and their immediate utility. In altered states of consciousness, however, humans are faced by another side of reality in which the spirituality inhabiting certain plants and animals reveals itself as yuxin, huni kuin, ‘our people’. Since it is manifested both as a vital force and as souls or spirits with their own will and personality, no term really captures the ephemeral and polyvalent nature of yuxin.

In the Purus region, the Kaxinawá themselves translate yuxin as ‘soul’ when referring to the yuxin who appear in human form at night or in the forest twilight. Use of this word comes from living close to the rubber-tappers, who also see and speak of souls. When speaking of the yuda baka yuxin or the bedu yuxin of the person, spirit is more frequently used: ‘It’s our spirit that sees, isn’t it? And that speaks’. Another translation used by the Kaxinawá is ‘enchanted’.

The activity of the shaman who seeks to learn about and relate with the yuxin is indispensable to the community’s welfare. The ultimate cause of every affliction, sickness or crisis can be traced to the yuxin side of reality in which the shaman, as a mediator between the two sides, is crucial. The shaman engages with the yuxin dimension of the world, with the category I call yuxinity. Places with a higher concentration of yuxin include river banks (where the mawam yuxibu live, identified by the place where they reside), lakes and trees.

The Kaxinawá say that the person is formed by flesh (or body) and yuxin. Animals have a corporal side and a yuxin side, so too plants. Among the animals, some have a strong and dangerous yuxin while others have a negligible yuxin power. The quality of the animal’s yuxin influences the diet and food taboos of human beings. The yuxin of plants are not usually noxious or dangerous. In many food fasts, banana and peanuts, for example, are allowed, even though the yuxin of these plants is regularly cited among the souls that appear in the village at the shaman’s request in order to cure. Amid all this ambiguity, the yuxin may appear as ‘real people’, huni kuin, as well as in the form of specific animals.

Muka: the power of the yuxin and the shaman

The power of the yuxin, revealed by its capacity for transformation, is called muka. Muka is a shamanic quality, sometimes concretized as a substance. Beings with muka have the spiritual power to kill and cure without the use of physical force or poison (‘remedy’: dau). The human being may receive muka from the yuxin, which clears the way for him to become a shaman, ‘pajé’, mukaya. Mukaya means a man with muka, or in Deshayes’s translation ‘pris par l’amer’ (‘caught by the bitter’). The shaman has an active role in the process of accumulating power and spiritual knowledge, but his initiation can only happen at the initiative of the yuxin. If the yuxin fail to choose or ‘capture’ him, his solitary treks in the forest come to nothing. Once caught, though, the apprentice becomes sick to the eyes of humans (‘they turn crazy when women come close’). While the weak point of the yuxin is the body, that of men is their yuxin; ‘yuxinity’ threatens the man’s body and his body, (female) blood, threatens the head of the yuxin.

A man who was caught who wishes to follow the path of a mukaya must submit to strict and prolonged fasts (sama) and find another mukaya to instruct him.

Another feature of Kaxinawá shamanism, expressed in the name mukaya, is the opposition between bitter (muka) and sweet (bata). The Kaxinawá distinguish two types of remedies (dau): sweet remedies (dau bata) are leaves from the forest, certain secretions, some animals and body decorations; the bitter remedies (dau muka) are the invisible powers of the spirits and the mukaya.

The speciality of the huni dauya (a man with sweet remedies, a plant healer) normally does not combine with that of the huni mukaya (shaman). The healer’s learning process is very different to the shaman’s. If he does not use poisonous leaves, the healer does not need to fast and may engage in his normal activities of hunting and married life. His knowledge is acquired through apprenticeship under another specialist and requires a good memory and keen perception.

The first sign that someone has the potential to become a shaman, a developed relationship with the world of the yuxin, is failure in hunting. The shaman develops such a deep familiarity with the animal universe (or with the yuxin of the animals), including being able to converse with them, that he is unable to kill them: “and walking in the forest, an animal speaks to me. When he sees the deer, he calls out ‘hey, my brother-in-law’, and he stopped still. When a peccary came, ‘ah’, he called, ‘ah, my uncle’, and he stopped. Then in our language he says ‘em txai huaí!’ (‘Hey, brother-in-law!’), so he doesn’t eat it” .

Consequently, the shaman doesn't eat meat and not just for affective reasons. The impossibility of eating meat is also linked to the muka and to the change in the senses of smell and taste of the person with matured muka in his heart. The taste and aroma of meat become bitter.

The shaman

The shaman is feared for his capacity to cause sickness and death without the need for physical action. He can shoot his muka (which is invisible when shot) into his victim from large distances, or he can persuade some of the yuxin with which he is familiarized to kill a person.

The larger the number of yuxin allied to the mukaya, the greater his power. Indeed, his power to cure resides in his capacity to negotiate as an active agent of the cure (when he goes to fetch the lost spirit of his patient residing among the yuxin) and in the quality and quantity of yuxin that he can convoke for a curing session, where the yuxin (his friends) act as agents of the cure working through (or gathered around) the shaman's body.

Even so, the shamanic voyage still remains a crucial feature of Kaxinawá shamanism. The bedu yuxin travels free of the body in dreams, or when the shaman is in a trance induced by snuff or ayahuasca. These journeys fulfil other objectives besides curing a concrete case of sickness. They are exploratory trips, seeking to understand the world and the ultimate causes of diseases. They explore the paths that the dead person’s bedu yuxin must follow to reach the sky and strengthen relations with the spiritual world for the community’s well-being.

Various types of sickness exist: material (poison) and spiritual (power). Poison-induced sicknesses are caused by the dauya (healer), while illnesses provoked by spiritual power (muka) have an enemy mukaya (shaman) at their source. A third type also exists: diseases caused by the yuxin, which involve the patient’s loss of his bedu yuxin. Diseases caused by the yuxin at the demand of a mukaya also mean a loss: the shaman’s muka may be stolen.

The two types of sickness caused by humans are treated in different ways. Poison provokes a loss of liquids and vital forces (the patient vomits, has diarrhoea and becomes anaemic). In this case, the shaman cures with his force: he inhales a type of snuff prepared especially for curing and blows it over the patient. When the cause is muka, the problem is not loss, but the presence of a negative force that takes the form of a foreign body that acts to destroy the body from the inside. Muka-provoked sicknesses include acute pains in the liver, stomach or heart (three important organs in the Kaxinawá view of the human body). In this phase, a cure is still possible. The shaman sucks the painful area of the body to remove the invading object – the muka which the enemy shaman sent into the patient.

Shamanic thought among the Kaxinawá acts in permanent, omnipresent form. Although public rituals and curing sessions are no longer performed, we need to consider their cosmovision within the wider context of the practices of their neighbours (Yaminawa, Kulina, Kampa), with whom the Kaxinawá have had increasingly close relations since ceasing to be enemies. Exchange between the groups is intense and may act as a stimulus for the Kaxinawá to revive their spiritual powers, stored in the memory of the forest.

For the Kaxinawá, the human person is conceived in three parts: the body or flesh (yuda), the body’s spirit or shadow (yuda baka yuxin) and the spirit of the eye (bedu yuxin). Flesh or any living body transforms into dust when its yuxin aspect is removed.

Shamanic initiation

There are various ways of being initiated into shamanism. Some result from a deliberate search on the apprentice’s part, others occur spontaneously due to the initiative of the yuxin who capture the chosen person unprepared. The presence of muka in the initiate’s heart, a condition sine qua non for any exercise of shamanic power, depends in the last instance on the will of the yuxin.

There are two ways in which the apprentice can increase the likelihood of an encounter with the yuxin so that these beings can plant the embryo of his muka in him: he may augment his dream experiences by sleeping a lot and using remedies (dripping the sap of certain leaves into his eyes or bathing water) in order to dream more and remember the dreams. Alternatively he may walk on a forest path, covering himself with embira or murmuru palm shoots (pani xanku) and aromatic leaves, singing and whistling to summon the yuxin.

The taste of things also provides information on their yuxin quality. Some things only a yuxin or animal will eat: husu, a blood-sucking nocturnal butterfly, is one of their preferred foods, along with mai xena, earthworms. But the idea of eating this fills humans with disgust. A person in a trance, under the effect of the yuxin, eats leaves as though they were food.

Another characteristic related to taste is that humans do not eat anything raw: at most a fruit from the forest, or in the case of children, a ripe banana when they are too hungry to wait for mealtime. It is also rare for someone to drink water. The yuxin, by contrast, typically eat raw things and are especially thirsty for raw blood: all animals and insects that suck blood are yuxin.

On being initiated, the young shaman must follow the paths indicated by smells, sounds and images that lead to contact with the yuxin. To avoid death, he needs to have a strong heart: death results from the collapse of the heart from fear. Collapse during initiation (death or madness) may occur due to the incapacity of the initiate/chosen one/victim to forge the bridge between the two sides of reality.

During the period which begins with the first ‘assault’ of the yuxin and ends when the muka has matured, the initiate shaman will show signs of weakness, yet this liminal phase is necessary to the process of learning from the yuxin. The apprentice is uninterested in social obligations and body processes because his mind is focused on the spiritual world. Most of the time he remains lying in his hammock or wanders randomly in the forest. However, these ‘symptoms’ are not interpreted as a sickness.

Myths

Most of the origin myths linked to a cultural item (fire, weaving, painting designs, pottery, planting etc.) tell how this item, or the art of producing it, was given to humans by an animal. But not just any animal. This animal ‘is an enchanted huni kuin’. Consequently, the yuxin within this animal communicated its qualities to humans. Not by chance, it was the squirrel that taught humans the art of planting (the squirrel has the habit of stocking food for lengthy periods, a practice necessary for planting). The capuchin monkey taught human beings how to copulate. This monkey adopts a face-to-face position during coitus, an exceptionally rare behaviour among animals. To ‘translate’ this animal habit into human behaviour, the yuxin transformed into people from a human perspective. Animals who lived in this form for some time among humans included the midwife rat (xuya), the weaver spider (Baxem pudu) and so on.

Social organization

The division between the sexes is fundamental to Kaxinawá society and marks quotidian life more than any other division into moieties, sections or ages. Generational difference is determined by a basic division in which children and old-aged people are grouped together due to their lower involvement with roles related to the construction of identity in gender terms and are differentiated as a group from men and women engaged in gendered productive activities.

The division of society into ritual and matrimonial moieties and into sections transmitting proper names does not permeate all activities, since most of the latter are undertaken either in the group of women or the group of men. During rituals, however, the division of society into moieties is important, as well as in a few male collective activities, such as swidden clearance.

The child's gender socialization begins very early. From the moment they succeed in walking unaided, they learn the easiest tasks appropriate to their gender. An infant receives his or her name soon after birth, but the time of infancy is needed to slowly link this name to the body of the new bearer. This happens during the first years of life through the repeated use of the name by the parents and later through the child's discovery of the correct use of kinship terms. As the infant learns these terms of reference and vocatives, the parents cease using his or her proper name and call the child only by kin terms.

Rituals

The set of rituals that occurs every three or four years during the xekitian, the green maize season (December and January), is called nixpupimá, Kaxinawá ‘baptism’. Nixpupimá is an initiation rite. From the moment they ‘commemorate’ nixpu for the first time, bakebu (children) become txipax and bedunan, girls and boys. They are differentiated by sex and ready to be initiated into the specific tasks and roles of their gender.

Nixpu is a forest plant whose stalk is struck repeatedly against the teeth, tingeing them a shining black. This effect is aesthetically beautiful to the Kaxinawá. In mythology, the black-beaked isa hana (Green-headed Tanager) is called nixpupiahawendua (‘beautiful because it ate nixpu’). Isa hana is a bird extremely concerned with beauty. Its own plumage is already resplendent: blue with a red tail. Isa hana saw that Bixku txamini had a body covered with scabies so fetid that his wife left him. Ixmi (the king vulture) came to eat him but Bixku defended himself and Ixmi lost many of his white feathers. Then Isa hana arrived and cured Bixku with medicinal plants in exchange for the white feathers that Ixmi had lost. Isa hana used these feathers to make a beautiful headdress to use in the nixpupima rite.

Blackened teeth form part of the make-up for festivals and rituals, along with applying genipap designs to the body and painting the whole body with red annatto paste (maxe), peanut oil (tama xeni) or peach palm oil (bani xeni), mixed with perfume (ininti), a custom that has now become rarer with the use of clothing. Nixpu is considered crucial to dental health: the Kaxinawá say that its sap strengthens and protects the teeth.

Txidin

Txidin takes place annually during xekitian, the green maize season, or after the funeral of somebody important (a chief or shaman). The longing and sadness provoked by the loss can affect the community’s vitality and well-being, and txidin serves to reinforce the belief in life and raise people’s spirits: its aim is to protect the living.

Txidin is characterized by the dewe songs (which tell of the creation of the world), by the dance of the song leader (txana xanen ibu) and his companion/apprentice who dances backwards with shells on his ankles, and by the clothing of the song leader. This is the only occasion when the cushima is used, a long robe covered in keneya (designs), a headdress (maite) of white feathers and red macaw tail feathers, the hawe (an adornment hung over the shoulders), eagle feathers and tails fabricated from the body feathers of various birds (kuxu dani, hana dani etc.) and the tail of the squirrel (kapa hina).

Thus decorated, the song leader represents the Inka and his allies: the eagle (tete), the king vulture (ixmin), and the txana. The Inka is linked to the moiety of the inubakebu (‘children of the jaguar’) and a wide set of symbolic associations surround him: maize, the cold, eternal life, genipap and the sun.

The moiety of the duabakebu (‘children of the shining’), on the other hand, is linked to the snake, the colour red, periodicity, putrescence and the moon. However, these are contextualized complementarities, such that the meaning of each element in the pair changes according to the situation.

Txidin forms part of the nixpupimá ritual sequence. The song leader in the nixpupimá dances around the fire lit close to the spot in the house where the recluses lie in their hammocks, circled by screens. He wears the clothing of the Txidin, the Inka, and the songs from the first part of the nixpupimá ritual tell of the visit of men (dua) to the village of the Inka (inu). Capistrano’s young informant told him that the preparations for the festival and Omã (nixpupimá) include embarking on a collective hunt, manufacturing small stools (kenan) and making the tene (the support for the eagle feather ornament), a decoration characteristic of the txidin. Afterwards nixpu and peach palm spines (banin muxa) are collected to perforate the lower lip and the nostrils. The first part of this initiation rite comprises an exhausting race from one side of the village patio to the other all day long, girls holding their mother’s hand and boys holding their father’s. The boys run with eagle feathers on their backs.

Katxanawá

A number of versions of katxanawá, a fertility ritual, exist and each may begin the nixpupimá ‘festival’. Normally katxanawá takes place several times per year. Visually the ritual is marked by the dance of the forest yuxin (covered from head to toe with tagua palm straw with exposed areas of the body painted with annatto) surrounding a hollow stilt palm trunk (tau pustu, katxa). The trunk is cut down and its bark and core removed in the forest by men from the moiety performing the ritual role of invader.

Before the missionary campaign against the use of alcohol, caiçuma – a fermented drink – was stored for six days inside the stilt palm trunk (covered with banana leaves) in order to ferment. The village danced for five days around the katxa and on the sixth day the guests from other villages arrived to consume the fermented brew (muxetan) with the hosts. Only one person told me that the fermentation was accelerated by spit (a custom still in use among the Katukina and Yaminawa).

During the visits, the contents of the katxa were emptied with people dancing and drinking all night. After being emptied, the same katxa was used as a receptacle for vomit: ‘vomiting helps stop us become soft; it’s like nixi pae (vine), which makes us vomit too to clean the stomach and become stronger. You vomit and can the stand more, right? You can then drink more, drink continually”. In the early morning, the katxa is taken back to the forest and destroyed.

The katxa symbolizes the uterus and the hollow trunk in which the first Kaxinawá were created. This female element is decorated with manioc and banana tubes, both male symbols. A group of men, all from the same moiety, begins to dance, emerging from the forest like yuxin and invading the village, singing ‘ho ho, ho ho’. This is the central element of the rite: the invaders from the forest initially get a hostile welcome: the other moiety which did not venture into the forest represents the ‘interior,’ the huni kuin, and grab their weapons to receive the enemies. But soon after approaching the forest yuxin, their weapons are put down and the two groups dance together around the katxa, calling all the cultivated plants by name.

As well as dancing and signing for an abundant harvest with the help of the forest yuxin, the katxanawá involves the ritual exchange of game and fish between the moieties. Thus a true katxanawá is preceded by a collective hunting trip, undertaken by each moiety separately and lasting from ten to fourteen days. One moiety gives hunt produce in the morning, the other returns the prestation at night. The same occurs with the dancing. On the first day, the inubakebu emerge from the forest and the duabakebu welcome them. On the second day the roles are reversed.

The katxanawá involves a complementary relationship between the sexes. Both men and women take part in the ritual – a participation with explicit sexual connotations. After invoking all the different kinds of banana, manioc and maize, the men began to sing insults and ritualized provocations at the women. The women immediately respond in kind and form a dance line with arms outstretched, holding onto the next woman's shoulder, and then run towards the circle of men trying to break it. The women’s songs have another rhythm and a much higher pitch than the men’s songs and they use this to try to make the men sing out of tune. This competitive trading of insults is called kaxin itxaka (insulting the ‘vampire bat’ – a metaphor for the vagina) and hina itxaka (insulting the tail –the penis), a joke that provokes a great deal of hilarity.

Festival of the new fire

This festival was performed with the katxanawá more than once a year and involved extinguishing the old fire and lighting a new fire in ritualized form, preceded by a collective hunt that provided enough smoked meat for several days of festival. The remains of the old fire were thrown away and on the day of lighting the new fire everyone went to bath before dawn. Today this fire has lost its raison d’être. Like their ancestors, the Kaxinawá now make a new fire every day.

Nixpupima

At night, the children are summoned to gather in the leader’s house. Only those children who have lost their milk teeth and gained their adult teeth are ready for initiation. Their hammocks are suspended in a corner of the house and surrounded by screens blocking any view of them.

Their mothers sit next to their children’s hammocks and begin to swing them, singing ‘kawa, kawa’. The children have to remain stretched out and cannot move. Any children who have to leave the hammocks must stare down at their feet. If they look at the sky or trees, a snake or an ant with a bite as strong as a snake may attack them. The children’s parents dance around the fire and sing pakadim, specific chants for their children to ‘become strong and learn swiftly’.

Early morning, the children take medicinal baths to grow and turn into hard workers (dayadau), while the girls receive a special bath to learn designs (kenedau). Both boys and girls also cut their hair at this time.

The children are painted black with genipap after bathing. They also wash their teeth with flat stones and sand to remove any impurities. After washing, the children may drink maize caiçuma (mabex).

A race is also held in the morning. The men take the boys by the hand and run with them from one side of the village patio to the other. When they stop to rest, it is the girls’ turn to run holding hands with the women. This continues throughout the day and the following two days. “Those who fall won't live for very long, those who don't fall will survive”. In the evenings after the race, the men sing the pakadim songs, as on the first night, and the women swing the children’s hammocks, singing ‘kawa, kawa’. The children eat nothing, drinking only mabex.

Between the races, the boys rest on the small stools (kenan) made by their parents for the occasion. The boy’s mother paints the stool with the sap from the leaves and trunk of the txaxuani tree, which exudes a black dye, and with maxepa (wild annatto), which dyes the wood a red colour. Among the motifs used is xunu kene (kapok tree design). The stool is made from the sacupima (air root, bema) of the sumaúma (xunu), a light, white wood. The xunu tree is very tall and considered a powerful entity by the Kaxinawá. It shelters giant yuxin (the nixu, hida yuxin).

The girls do not receive stools, nor do they drink nixi pae (the hallucinogenic ayahuasca drink). Women customarily sit cross-legged on a mat while the men sit on a stool (kenan, tsauti), a turtle shell, an upturned xaxu or, when the man is the oldest of the house or an important visitor, a hammock made for sitting (hisin).

In the evening on the last day of the races, the children receive a plate with nixpu when they lie down in their hammocks. They chew this until their teeth turn black. After this they fast (samake) for five days: they can only drink maize caiçuma. They can eat again when the black has disappeared from their teeth: in other words, when they have left the liminal phase marked by the black colouring.

Dau

The dau category includes white people’s remedies, body adornments and treatments, and phytotherapy. To be attractive and beautiful, the Kaxinawá wash themselves frequently (twice a day), remove all their body hair, paint themselves red with annatto paste mixed with oil (not overdoing the colour, or else they will look like the Kulina, considered ugly) and cover themselves with genipap designs. Nails are cleaned and cut with a fine stone, teeth brushed with sand and stones, and hair and face washed with white clay. To shave, the men spread ashes on their chins and remove the stubble with a shell (a practice I was unable to verify through observation). In the past, women plucked their eyebrows.

Before clothing became widespread, men, women and children wore white cotton bands (huxe) on their wrists, ankles and arms (puxte), necklaces (teuti) made from black beads (meimatsi) and bands of cotton or beads crossed over the chest (mane haxkanti). The men used a fine belt (tinetxi) which held the penis, while women wore cotton skirts (xanpana) painted with perfumed annatto dye. Men and women used adornments in the piercings on their lower lips (cotton, beads or a thin piece of wood: mane keu), ears (pau) and nose (one or various white or blue beads: dexu), as well as a cotton thread between the nose and ears (dedi). In the festivals men also used macaw feathers through their nostrils (demu) and headdresses. The bands, necklaces and belts (or skirts) were also used to suspend various types of dau: aromatic leaves, monkey, jaguar and cayman teeth (the latter is held to protect people from snakes), various types of beads and shells, and pieces of animal hide.

Marriage

After the first menses, the interest of the village’s men in the young woman becomes permissible. The suitors begin to appear and sooner or later she must marry. For the first marriage, the young woman’s parents consider her kinship relations with the young and unmarried men of the community. It is important for the husband to be a close cross-cousin, preferably someone from the same village.

Before marriage the mother consults the daughter and the suitor consults the mother. She then speaks with her husband, then with the suitor’s mother and finally the suitor asks to marry the girl in front of her parents. The step from courting to marriage takes place when the young man leaves his parents’ home and goes to sleep in the house of his parents-in-law. If he already has another wife, the man builds a house for himself close to his father-in-law where he goes to live with his wives.

On the morning after the first night, the new couple and their respective parents go to the leader’s house. The leader instructs the bridegroom in the duties of a good husband: he must make a swidden for his wife, plant lots of banana, manioc and maize, be a good hunter, look after their children, and show her affection. The leader tells the bride that she must take good care of her husband, prepare food for him, offer food to his visitors, weave his hammock, wash his clothing, show him affection and look after their children. After this sermon, and after drinking the porridge offered to them by the leader’s wife, the couple returns to the bride’s parents’ house and the bridegroom’s parents return to their own.

Marriage is not celebrated with a festival or other ceremony. From the moment when a man and woman live in the same house, the expectation is for her to become pregnant quickly. The marriage is only considered consummated after the birth of the first child (infertility provides sufficient grounds for separation). The girl ceases to be an adolescent (txipax) and becomes a woman not after marriage but when she becomes a mother.

Art

Kene Kuin, the true design, is an important emblem of Kaxinawá identity. Neighbouring peoples (the Kulina, Yaminawa and Kampa) have no designs comparable to kene kuin. For the Kaxinawá, these designs are a crucial element in the beauty of persons and things.

The body and face are painted with genipap during festivals, when visitors arrive or for the simple pleasure of dressing up. Small children are not painted with designs but are blackened from head to foot with genipap. Boys and girls have just part of their face covered with designs while adults paint their entire face.

Painting with genipap is an exclusively female activity. On days without any festival, they walk around unpainted, but when one of the men from the house brings genipap from the forest, there is always someone eager to mix the paint and invite the others to paint themselves. Young women are the most likely to be seen painted with designs, men less frequently, unless they are acting as hosts.

The kene kuin style contains a variety of named motifs. When a motif has two or more names, this is generally because of the ambiguity between figure and ground typical to the Kaxinawá aesthetic. The same motifs or basic designs used in face painting are found in body painting, pottery and weaving, basketry and stool decorations.

Just as not all bodies are painted, or not some bodies all of the time, not all keneya objects have designs. Cooking vessels are not painted, though the plates for serving food may be. Painting is associated with a new phase in the life of the object or person, a phase in which it is desirable to emphasize the smooth and perfect surface of the body in question. The design calls attention to new visual experiences, which announce crucial life events. The design vanishes with use and is only reapplied during festivals. Hence things with design occupy a special place in Kaxinawá culture, as in other cultures of western Amazonia.

<object height="344" width="425"> <param name="movie" value="http://www.youtube.com/v/JxaP8WFyBqo&color1=0xb1b1b1&color2=0xcfcfcf&hl=en_US&feature=player_embedded&fs=1"/> <param name="allowFullScreen" value="true"/> <param name="allowScriptAccess" value="always"/><embed allowfullscreen="true" allowscriptaccess="always" height="344" src="http://www.youtube.com/v/JxaP8WFyBqo&color1=0xb1b1b1&color2=0xcfcfcf&hl=en_US&feature=player_embedded&fs=1" type="application/x-shockwave-flash" width="425"/></object>

Productive activities

Female work

Kaxinawá cooking is highly diverse. Women make a porridge from large quantities of ripe, sweet banana pulp – mani mutsa; they also prepare manioc, sometimes with the ground up green leaf of the plant or with nawanti or xiwan, forest leaves with a taste similar to chicory, slightly acid, or with toasted and ground peanuts, or simply unadulterated. Women also cook green banana and, if there is any maize, make caiçuma (mabex) from toasted and ground maize, with or without peanuts.

When one of the men from the house returns with game, the women burn the animal’s pelt and butcher it straight away. Some parts are roasted, others boiled. The cooking stock is mixed with various herbs: a kind of coriander, types of saffron and ginger (xawaxuanti, xiada), pepper (yutxi), sometimes annatto(maxe), some unidentified herbs and salt. Fish may be roasted when large but is generally cooked in a broth or minced and roasted in a banana leaf with mushrooms. Another recipe from Kaxinawá cooking is beten, a paste made from maize flour (dudu), sweet manioc or roasted and pulped banana, mixed with the broth and the meat from small game, along with palm heart when available.

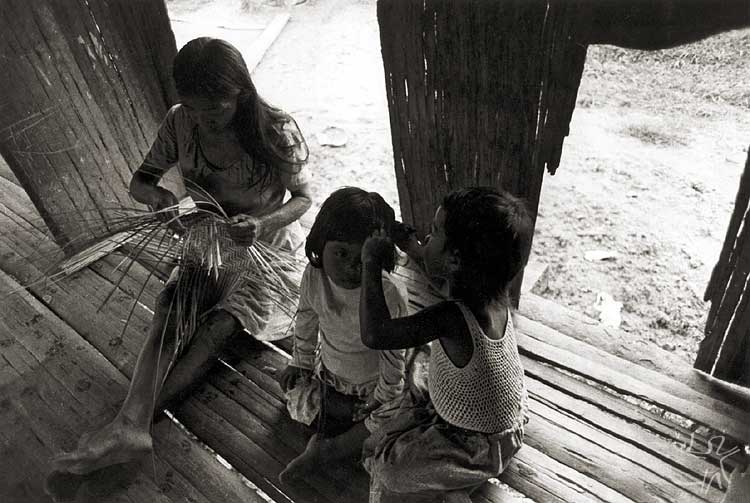

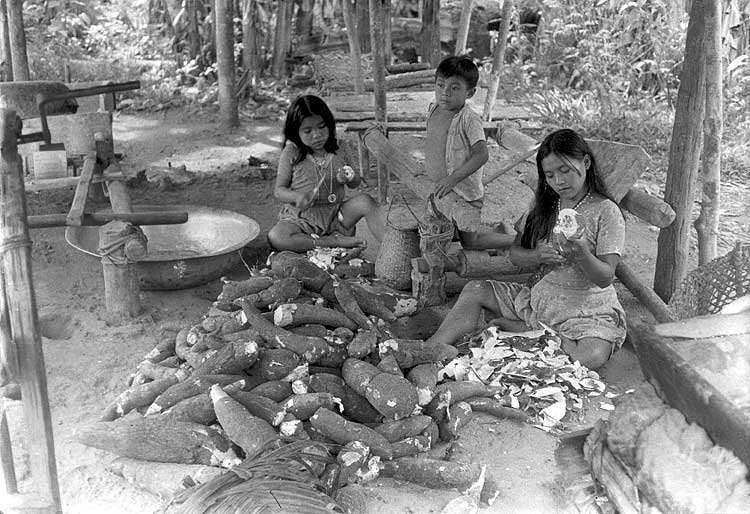

Kaxinawá cookery is laborious and demands several hours work per day. Girls between eight and twelve years old take part in minor culinary tasks such as peeling manioc or tending the fire, while babies have to be left with younger sisters. Another common task for girls of this age is fetching water from the well.

As well as preparing the evening meal during the day, women go daily to the creek with their children, mother and one or two sisters and their own children (boys only up to the age of seven; after this they bathe in the river with the men). The women wash clothes while the children play in the water.

Every two or three days a woman will go with other women with neighbouring swiddens to collect bananas and manioc. They cut down the banana tree with a few blows from a machete and then remove the bunch. To extract manic, they chop down the plant, remove the earth from around the roots with an axe and pull the tubers up by hand, taking care not to snap them in half. After removing the tubers, they cut to 15 cm lengths of the plant stalk and bury them (this type of planting is not called bana, but ‘replanting,’, kaban); the leaves are taken back to the house to use as a condiment. Other vegetables such as potato, yam and other root crops are seasonal and do not form part of the staple diet.

Normally planting is undertaken by men while women harvest the crop. Peanuts, though, are only ever planted by men and women together. Other exceptions to this rule are cotton, annatto and beans, which are planted by women. The planting of peanuts on the beach is turned into a festival. Half of the village goes: children, men and women. After clearing the terrain, the men walking in a straight line place a peanut in each hole. As they work, people sing the peanut pakadin.

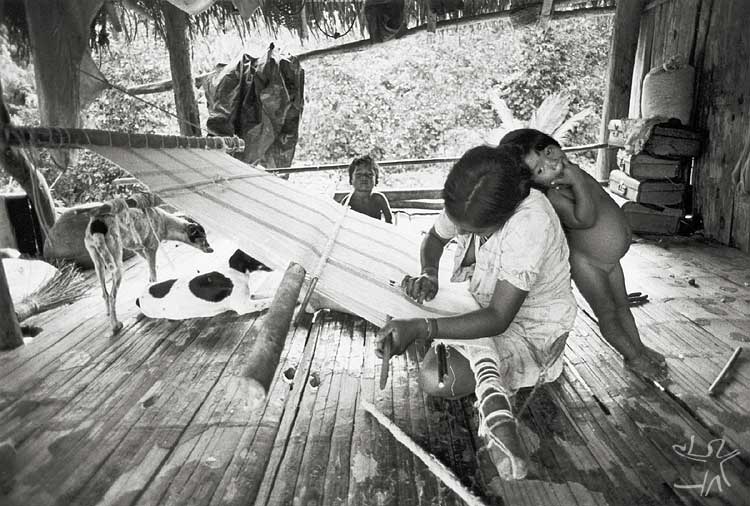

As well as swidden work, washing clothes and cooking, women also work with cotton. I arrived after the cotton had been harvested and observed the processes of drying in the sun, opening, beating, spinning, dyeing and weaving. In these weeks of collective female work, all (or almost all) the village’s women appear at dawn at the house of the women whose cotton is to be spun that day. The cotton will have been prepared previously by each woman individually or with the women from her house. All the cotton from one house is spun in a day. During these weeks of work, other activities depending on the women are almost suspended. The women explained to me that this hectic pace was far from ideal, but was intended for sale, otherwise they would have worked more calmly.

Txipax (initiated adolescents) take part in this collective activity only after learning the art of spinning at home. ‘If not, the others will laugh.’. Kensinger (an anthropologist who worked among the Kaxinawá in the 1950s and 60s) writes that while learning how to spin, the txipax avoids eating stingray (Kensinger, 1981).

Other female activities include making baskets (txuxan), fans (paiati) and mats (pixin). These baskets are for household use: some are employed to store and serve food, others – larger and more open – to collect cotton, and others still to hold personal items: needles, threads, ear decorations, annatto paste, perfume, etc. The design motifs used on these baskets have the same name as some of the motifs used on hammocks and in facial and body painting.

Not all the baskets, though, are made by women. The kakan used to carry firewood and the kuki used to carry banana and manioc – both large models, suspended from the forehead and carried on the back – are made by men, despite being used by women. The kunpax is a makeshift basket fashioned from leaves at the spot where game was killed by the hunter. Finally, the bunanti is a round box made from wild cane leaves (hewe tawa) by men to store their feathers.

The Kaxinawá draw a fundamental distinction between ‘planted’ and ‘from the forest.’. This distinction also applies to the material from which the basket is made: “men make baskets from wild canes taken from the forest; women only work with planted cane.”. Women’s baskets are for internal use only: “a woman doesn't make the basket for the man to store his feathers, no way. She can’t!” (Antônio).

Some twenty years ago, pottery was still one of women’s routine tasks and part of the girl's learning. Now the clay pots have been replaced by aluminium pans. “Aluminium pans are lighter and don’t break,”, people argue, “but they are expensive and never as large as the pots with which we use to make caiçuma. For festivals these small pans are useless” (Maria D.).

Male work

The main activity learnt by boys is hunting. In 1955 Kensinger (1975: 28) found the Kaxinawá using bows and arrows only. In 1963 everyone was already using rifles, but always with a bow by their side. It was common to see boys from two years onwards practicing with a bow and arrow, made to their size by their father or txai (maternal grandfather). I saw few boys with a bow. But the older men continue to take a bow with them on their treks through the forest and each house has its bows and the three types of arrow. In many cases, the men share a rifle. I saw one case where three men used the same gun, because one of the three had exchanged his rifle for a record player.

When a boy reaches the age of eight or nine, he begins to accompany his father on the hunt. Only after initiation can the bedunan (initiated adolescent) venture out alone or in the company of a brother or brother-in-law. Hunting has more secrets than just a good aim and a good eye. The boy learns to observe the habits of each kind of animal, to recognize their tracks (kene), and to imitate their cries and whistles.

When the boy is learning to hunt a certain type of animal, he ceases to eat it for the period of this specific initiation. The hunter should also avoid eating the meat from inferior parts of the animal: the head is the best, but hunters do not eat the head of an animal they themselves have killed, only the head of prey given to him by his txai. The apprentice avoids eating the first game he kills, or else he could become ‘panema’ (unlucky). He is only considered a true hunter after killing a large animal such as a tapir, deer or peccary. When this happens, he is splattered with the blood of the animal he killed (Kensinger, 1975: 29).

Luck in hunting is crucial to a man’s prestige; however the causes of bad luck are not always clear. Many remedies (dau) and ritualized practices therefore exist to try to attain the status of a marupiara (good hunter). The bow (kanu) is treated with a degree of reverence: ‘Only happy women can touch the bow.’. After killing a large game animal, the hunter usually wipes the bow with its blood, though ‘we don’t do this with rifles.’

Before planting, the terrain is cleared of vegetation and burnt, both activities being undertaken in a group. The swidden clearance is a direct confrontation with the yuxin of the forest, explaining why the process is accompanied by war cries and the men paint themselves with annatto (red is the colour of the forest yuxin). They also inhale snuff to make themselves strong and courageous. While the men set fire to the swidden and yell, their faces painted red, some one hundred metres away the women sing to the yuxin for the latter to give them a strong fire and abundant crops. Afterwards a collective meal is offered with abundant food.

Most of the fishing techniques also belong to the male domain. The Kaxinawá use two types of timbó: the puikama leaf and the sika root. The most frequently used is puikama, a planted bush whose leaves and flowers are gathered by women and ground by men in a mortar used solely for this purpose. This paste is then made into balls (tunku) weighing about one kilo and kept in bags impermeabilize with rubber, or in baskets covered with banana leaves.

This type of fishing is also undertaken by women. When the wives and grandmothers of the house prepare a small expedition with their children, they pound enough to make two or three balls and head off to a small creek. The balls of timbó are diluted (mutsa) in the water and the poison has an almost instantaneous effect on the fish, which, intoxicated, begin to thrash and rise to the surface. Children, women and old men wade through the water with a conical net and strike the water (kuxawe). The bigger fish are caught by hand, which demands a certain amount of agility and skill.

Lake fishing is more risky and only undertaken by groups of men. Here sika is used, a highly poisonous root capable of killing a person. The lake is inhabited by many powerful animals and yuxin: the cayman (kape), anaconda (dunuan), piranha (make), yuxin kudu, a water monster, and kuxuka, the river dolphin, ‘who cries like a person, looks like a person, is a person, yuxin.’

Hook and line fishing was traditionally practiced by the Kaxinawá. Even before contact with non-Indians, hooks were cut from the junction of the ulna and the radius bones of the armadillo, while the fishing line was made from embira fibre.

During earlier periods when the Kaxinawá lived in the upland areas away from the rivers, fishing was a secondary activity compared to hunting. Today, though, fishing is just as important as hunting and equally appreciated. The meat of the cayman (kape) – hunted from a canoe in the river at night (during the new or waning moon, since the full moon, uxe badi: sun-moon, is too bright) with bin (a caucho torch) and, when there are batteries, with nawan bin (torch) – is highly appreciated, as is the soft and oily meat of the stingray.

Wild fruits may be gathered by women or, if chopping down or climbing a tree is necessary, by a man, his wife and some of their children. This applies to gathering assai (pana), patoá (isa), sapota (itxibin), jaci (kuti), aricuri (xebum), bacaba (pedi isan) and palm heart. Other fruits are eaten when found on the path: xena and xakapei, types of wild beans that grow on vines, with a white and sweet pulp containing the seeds. I also ate an orange-coloured fruit (bumpe) and murmuru fruit (panikwa). Other fruits and various kinds of mushrooms are also gathered.

Men usually bring fruits home when they have been unable to kill anything. Cacao is one of the favourites. The seed is discarded, only the sweet white pulp surrounding it is eaten. Men also bring the genipap that women use to make the paint for body designs.

In terms of rubber production, the Kaxinawá produce much less than the rubber-tappers living exclusively from the latex. For the Kaxinawá of the Purus (in contrast to those living on the Jordão and Envira rivers), rubber only provides a small source of income to buy ammunition or salt from time to time, when a river trader visits (which is infrequently). The largest source of income in Cana Recreio and Moema is women’s weaving. The sale of hammocks and small bags in Rio Branco enables the leaders to supply the community’s kitchen.

Notes on the sources

The Kaxinawá are the most well-known Pano group with a copious ethnological and historical literature existing on them. The first writings on the people appeared at the start of the 20th century from the pen of the French priest, Constantin Tastevin (1919, 1920, 1925a, 1925b, 1925c, 1926; Rivet & Tastevin, 1921), who describes the customs of the Kaxinawá who he met during his travels through the Juruá-Purus river basin. Also during the first two decades of the last century, a collection of extremely valuable Kaxinawá narratives and myths was produced by Capistrano de Abreu (1913, 1941, 1969) with an interlinear transcription and translation.

Kenneth Kensinger was the first anthropologist to live with the Kaxinawá, in Peru. Kensinger produced a vast collection of works and articles on virtually all topics relating to Kaxinawá life and society. The generation of anthropologists that succeeded Kensinger continued to develop the questions raised and discussed in his works.

Also in Peru, the Kaxinawá were studied by Keifenheim and Deshayes (1982, 1990, 1992, 1994). Both authors focus on the themes of identity, alterity and the classificatory systems. Marcel D’Ans (1973, 1978, 1983) studied the colour naming and classification system and produced a compendium on mythology.

In Brazil the Kaxinawá were studied by Aquino (1977), Iglesias (1993) and Lindenberg (1996), on the Jordão river, who centre their research on the themes of interethnic relations and education.

The Kaxinawá of the upper Purus river, the same group with which I obtained the data for my own ethnographic research, were studied by McCallum. McCallum’s work focuses on social organization and gender relations. Part of her study of the later involves an analysis of the Katxanawa ritual.

The studies of Kensinger, Deshayes and Keifenheim and McCallum provide the ethnographic and ethnological framework for my own work, which combines what I learnt from their writings and my own field observations, which I looked to direct towards areas of interest that had been underexplored.

In my master’s dissertation – Uma etnografia da cultura Kaxinawá: entre a Cobra e o Inca, completed in 1991 – I looked to dialogue with the literature on the Kaxinawá and other Pano groups, closely linking my own findings with those of the authors mentioned above. In my doctoral thesis – Caminhos, duplos e corpos. Uma abordagem perspectivista da identidade e alteridade entre os Kaxinawá, presented in 1998 – I sought to construct an ethnography based around the ideas and concepts of the Kaxinawá themselves. Although it uses the literature on the Kaxinawá in particular and on the Pano in general as a reference point, the work was conceived as an ethnography based and built on the material derived from my own research.

Sources of information

- ABREU, J. Capistrano de. Os Caxinauás. Ensaios e Estudos (Crítica e História), s.l. : s.ed., 3ª. Série, p.174-225, 1969 (1911-12, 1ª. Ed. ).

- --------. Rã-txa hu-ni-kui : A língua dos Caxinauás do Rio Ibuaçú. s.l. : s.ed., 1941 (1914, 1ª.Ed.).

- AQUINO, Terri Valle de. Índios Caxinauá : de seringueiro caboclo a peão acreano. Rio Branco : s.ed., 1982. 184 p. Originalmente Dissertação de Mestrado pela UnB de 1977.

- AQUINO, Terri Valle de; IGLESIAS, Marcelo Manuel Piedrafita. Kaxinawa do rio Jordão : história, território, economia e desenvolvimento sustentado. Rio Branco : CPI-AC, 1994. 272 p.

- --------. Zoneamento ecológico-econômico do Acre : terras e populações indígenas. Rio Branco : s.ed., 1999. 179 p.

- BENAVIDES, Margarita. La economia de los Kaxinawá del rio Jordão, Brasil. In: SMITH, Richard Chase; WRAY, Natalia (Eds.). Amazonia : economia indígena y mercado - Los desafios del desarrollo. Quito : Coica ; Lima : Oxfam América, 1995. p. 128-83.

- CALAVIA SAES, Oscar. A variação mítica como reflexão. Rev. de Antropologia, São Paulo : USP, v. 45, n. 1, p. 7-36, jan./jun. 2002.

- CAMARGO, Eliane. Alimentando o corpo : o que dizem os Caxinauá sobre a função nutriz do sexo. Sexta Feira: Antropologia, Artes e Humanidades, São Paulo : Pletora, n. 4, p. 130-7, 1999.

- --------. Les differents traitements de la personne dans la relation actancielle : l’example du Caxinaua. Actances, s.l. : s.ed., n. 8, p. 1-25, 1994.

- --------. Elementos da base nominal em Caxinauá (Pano). Boletim do MPEG: Série Antropologia, Belém : MPEG, v. 13, n. 2, p. 141-65, dez. 1997.

- --------. Enunciação e percepção : a informação mediatizada em Kaxinawá. Bulletin de la Soc. Suisse des Américanistes, Genebra : Soc. Suisse des Américanistes, n. 59-60, p. 181-88, 1995-1996.

- --------. Esboço fonológico do kaxinauá (Pano). Boletim do MPEG, Série Antropologia, Belém : MPEG, v. 9, n. 2, p. 209-28, 1995.

- --------. Gragando o ágrafo : um ponto de vista lingüístico a partir do caxinauá. In: SILVA, Aracy Lopes da; FERREIRA, Mariana Kawall Leal (Orgs.). Antropologia, história e educação : a questão indígena e a escola. São Paulo : Global, 2001. p. 360-96.

- --------. Phonologie, morphologie et syntaxe : étude descriptive de la langue caxinaua (Pano). Paris : Univ. Paris IV, 1991. 448 p. (Tese de Doutorado)

- CUNHA, Manuela Carneiro da; ALMEIDA, Mauro Barbosa de (Orgs.). Enciclopédia da floresta - o Alto Juruá : práticas e conhecimentos das populações. São Paulo : Companhia das Letras, 2002. 736 p.

- D’ANS, Andre-Marcel. Le dit des vrais hommes : mythes, contes, legendes et traditions des indiens Cashinahua. Paris : Gallimard, 1991. 392 p. (L’Aube des Peuples)

- --------; CORTEZ, M. Terminos de colores Cashinahua (Pano). Centro de investigacion de lingüistica aplicada, Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos, Lima, 1973. (Documento de Trabajo, 16)

- DESHAYES, Patrick. La conception de l'Autre chez les Kashinawa. Paris : Université de Paris VII, 1982. (Tese de Doutorado).

- --------. Paroles chassées : chamanisme et chefferie chez les Kashinawa. Journal de la Société des Américanistes, Paris : Société des Américanistes, v. 78, n. 2, p. 95-106, 1992.

- --------; KEIFENHEIM, Barbara. Penser l’autre. Chez les indiens Huni Kuin de l’Amazonie. Paris : L’Harmattan, 1994.

- ERIKSON, Philippe et al. Kirinkobaon kirika (“Gringos’ Books”) : an annotated panoan bibliography. Amerindia, Paris : A.E.A., n. 19, 152 p., supl., 1994.

- --------; CAMARGO, E. Caxinauá, mais guère amazonienne : qui sont-elles? Les devinettes transcrites par Capistrano de Abreu. Journal de la Société des Américanistes, Paris : Société des Américanistes, n. 82, p. 193-208, 1996.

- FUNDAÇÃO DE CULTURA E COMUNICAÇÃO ELIAS MANSOUR; CIMI. Povos do Acre : história indígena da Amazônia Ocidental. Rio Branco : Cimi/FEM, 2002. 58 p.

- GAVAZZI, Renato Antônio (Org.). Geografia Kaxinawá. Rio Branco : Kene Hiwe/CPI-AC, 1994.

- --------. Observações sobre uma sociedade ágrafa em processo de aquisição da língua escrita. Em Aberto, Brasília : INEP, v. 14, n. 63, p. 151-9, jul./set. 1994.

- GRUPIONI, Luis Donisete Benzi. O ponto de vista dos professores indígenas : entrevistas com Joaquim Mana Kaxinawa, Fausto Mandulao Macuxi e Francisca Novantino Pareci. Em Aberto, Brasília : Inep/MEC, v. 20, n. 76, p. 154-76, fev. 2003.

- GUIMARÃES, Daniel W. Bueno. De que se faz um caminho : tradução e leitura de cantos Kaxinawa. Niterói : UFF/PPGLetras, 2002. 290 p. (Dissertação de Mestrado)

- IGLESIAS, Marcelo Manuel Piedrafita. O astro luminoso : associação indígena e mobilização étnica entre os Kaxinawá do rio Jordão. Rio de Janeiro : UFRJ, 1993. 417 p. (Dissertação de Mestrado)

- --------. A indenização dos ocupantes não índios no processo de regularização de terras indígenas : considerações do Estado do Acre. In: GRAMKOW, Márcia Maria (Org.). Demarcando terras indígenas II : experiências e desafios de um projeto de parceria. Brasília : Funai/PPTAL/GTZ, 2002. p. 169-203.

- --------. Territorialidade Kaxinawá no Jordão dos anos 90. In: KASBURG, Carola; GRAMKOW, Márcia Maria (Orgs.). Demarcando terras indígenas : experiências e desafios de um projeto de parceria. Brasília : Funai/PPTAL/GTZ, 1999. p.83-98.

- --------; AQUINO, Terri Valle de. Os Kaxinawá e os brabos : territórios indígenas e deslocamentos populacionais nas fronteiras do Acre com o Peru. Travessia, São Paulo : s.ed., v. 9, n. 24, p. 29-38, jan./abr. 1996.

- JEFFRAY, Christian. La dette imaginaire des récolteurs de caoutchouc. Cahiers des Sciences Humaines, s.l. : s.ed., v. 28, n. 4, p. 705-25, 1991.

- KAXINAWA, Joaquim Maná Paula (Org.). Nuku Minawa, nossa música. Rio Branco : Kene Hiwe Ltda, 1995. 67 p.

- --------; MONTE, Nietta Lindenberg (Orgs.). Shenipabu Miyui : história dos antigos. Rio de Janeiro : Jacobina, 1995.

- KEIFENHEIM, Barbara. Untersuchungen zu den Wechselbeziehungen von Blick und Bild : die Kasinawa-Indianer und Ihre Ornamentik (Ost-Peru). Berlin : Freien Universitat, 1998. 260 p.

- --------. Wege der Sinne : Wahrnehmung und Kunst bei den Kashinawa-Indianern Amazoniens. Frankfurt : Campus, 2000. 280 p.

- KENSINGER, Keneth M. Cashinahua medicine and medicine men”. In: Lyon, P. (Ed.). Native South Americans : Ethnology of the least known continent. Boston : Little, Brown and Co., 1974

- --------. Disposing of the dead in Cashinahua society. Lat. Am. Anthropol. Rev., s.l. : s.ed., v. 5, n. 2, p. 57-60, 1993.

- --------. Feathers make us beautiful : the meaning of Cashinahua feather headdresses. In: REINA, R.; KENSINGER, Kenneth M. The gift of birds : featherworking of native South American peoples. Filadelfia : Pennsylvania University, 1991. p. 40-9.

- --------. Food taboos as markers of age categories in Cashinahua society. Working Papers on South American Indians, v.3, p.157-72, 1981.

- --------. How real people ought to live : the Cashinahua of Eastern Peru. Prospect Heights : Waveland Press, 1995. 307 p.

- --------. Return to the Cashinahua. Quadrille, s.l. : s.ed., v. 25, n. 3, p. 27-9, 1993.

- -------- et al. The Cashinahua of Eastern Peru. s.l. : Haffenreffer Museum of Anthropology, 1975. 238 p. (Studies in Anthropology and Material Culture, 1).

- KERFENHEIM, Barbara. Zur Bedeutung Drogen-induzierter Wahrnehmungen bei den Kashinawa-Indianern Ost-Perus. Anthropos, s.l. : s.ed., v. 94, n. 4/6, p. 501-14, 1999.

- LAGROU, Elsje Maria. Caminhos, duplos e corpos : uma abordagem perspectivista da identidade e alteridade entre os Kaxinawá. São Paulo : USP, 1998. 366 p. (Tese de Doutorado)

- --------. Uma etnografia da cultura kaxinawá : entre o cobra e o Inca. Florianópolis : UFSC, 1991. 228 p. (Dissertação de Mestrado)

- --------. Uma experiência visceral : pesquisa de campo entre os Kaxinawá. In: Grossi, M. (Ed.). Pesquisa de campo e subjetividade. Florianópolis : PPGAS/ UFSC, 1993.

- --------. Hermenêutica e etnografia : uma reflexão sobre o uso da metáfora da textualidade para “ler” e “inscrever” culturas ágrafas. Revista de Antropologia, São Paulo : USP, v.37, p. 35-55, 1995.

- --------. Poder criativo e domesticação produtiva na estética piaroa e kaxinawá. Cadernos de Campo, São Paulo : USP, v. 5, n. 5/6, p. 47-61, 1995/1996.

- --------. Xamanismo e representação entre os Kaxinawá. In: LANGDON, E. J. (Ed.). Xamanismo no Brasi : novas perspectivas. Florianópolis : Ed. UFSC, 1996.

- LEÃO, Luciana Ladeira da Rocha. Kaxinawá. In: GONÇALVES, Marco Antônio Teixeira (Org.). Acre : história e etnologia. Rio de Janeiro : Núcleo de Etnologia Indígena/UFRJ, 1991. p. 201-24.

- MAIA, Dede. Kene : a arte dos Huni Kui. Rio de Janeiro : Dede, 1999. 32 p.

- MANA, Joaquim Paulo de Lima (Org.). Huni kuine miyui. Rio Branco : CPI-AC ; Brasília : MEC, 2002. 72 p.

- MAHER, Terezinha de Jesus Machado. Ser professor sendo índio : questões de lingua(gem) e identidade. Campinas : Unicamp, 1996. p.261 p. (Tese de Doutorado).

- McCALLUM, Cecília. Alteridade e sociabilidade Kaxinawa : perspectivas de uma antropologia da vida diária. Rev. Bras. de Ci. Soc., São Paulo : Anpocs, v. 13, n. 38, out. 1998.

- --------. Aquisição de gênero e habilidades produtivas : o caso Kaxinawá. Estudos Feministas, Rio de Janeiro : UFRJ/IFCS, v. 7, n. 1/2, p. 157-75, 1999.

- --------. The body that knows : from Cashinahua epistemology to a medical anthropology of Lowland South America. Medical Anthropology Quarterly, s.l. : s.ed., v. 10, n. 3, p. 347-72, 1996.

- --------. Comendo com Txai, comendo como Txai : a sexualização de relações étnicas na Amazônia contemporânea. Rev. de Antropologia, São Paulo : USP, v. 40, n. 1, p. 109-47, 1997.

- --------. Gender, Personhood ans social organization amongst the cashinahua of Western Amazonia. Londres : Univ. of London, 1989. 446 p. (Tese de Doutorado)

- --------. Incas e Nawas : produção, transformação e transcendência na história Kaxinawá. In: ALBERT, Bruce; RAMOS, Alcida Rita (Orgs.). Pacificando o branco : cosmologias do contato no Norte-Amazônico. São Paulo : Unesp, 2002. p. 375-404.

- --------. Language, kinship and politics in Amazonia. Man, Londres : Royal Anthr. Inst. of Great Britain Ireland, v.25, n.s., p. 412-33, 1990.

- --------. Morte e pessoa entre os Kaxinawá. Mana, Rio de Janeiro : Museu Nacional, v. 2, n. 2, p. 49-84, out. 1996.

- MONTAG, Richard. Cashinahua folklore : a structural analysis of oral tradition. Arlington : Univ. of Texas, 1992. 171 p. (Masters of Arts in Sociology)

- --------. A tale of pudicho’s people : Cashinahua narrative accounts of European Contact in the 20th Century. New York : University at Albany State University of New York, 1998. (Dissertação).

- MONTE, Nietta Lindenberg. A construção de currículos indígenas nos diários de classe : estudo do caso Kaxinawá/Acre. Niterói : UFF, 1994. 212 p. (Dissertação de Mestrado)

- --------. Escolas da floresta : entre o passado oral e o presente letrado. Rio de Janeiro : Multiletra, 1996. 246 p.

- -------- (Ed.). O jacaré serviu de ponte : Estórias de hoje e de antigamente dos índios do Acre. Rio Branco : CPI-Acre, 1984.

- OLIVEIRA, Maria da Conceição Maia de; DINIZ, Keilah. A escola Kaxi. In: SILVA, Aracy Lopes da. A questão da educação indígena. São Paulo : Brasiliense ; CPI, 1981. p. 30-7.

- RICCIARDI, Mirella. Vanishing Amazon. Londres : Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1991. 240 p.

- RIVET, P.; TASTEVIN, C. Les tribus indiennes des bassins du Purus, du Juruá et des régions limithrophes. La Géographie, s.l. : s.ed., v.35, p. 449-82, 1921.

- SANTOS, Lenize Maria Wanderley. STRs autossômicos e ligados ao cromossomos y em indígenas brasileiros. Ribeirão Preto : FMRP, 2002. 131 p. (Tese de Doutorado)

- SCHULTZ, H.; CHIARA, W. Informações sobre os Índios do Alto Purus. Revista do Museu Paulista, São Paulo : Museu Paulista, n.s., v.9, p. 181-201, 1955.

- SENA, Vera Olinda; MAHER, Tereza; BUENO, Daniel (Orgs.). Histórinhas indígenas da floresta. Rio Branco : CPI-AC, 2001. 84 p.

- SENA, Vera Olinda; MONTE, Nietta Lindenberg. Kene, livro de leitura Kaxinawá. Rio Branco : CPI-AC, 1993. 90 p.

- SILBERLING, Louise; FRANCO, Mariana Pantoja; ANDERSON, Anthony B. Couro vegetal : desenvolvimento de um produto artesanal para o mercado. In: ANDERSON, Anthony; CLAY, Jason (Orgs.). Esverdeando a Amazônia : comunidades e empresas em busca de práticas para negócios sustentáveis. São Paulo : Peirópolis ; Brasília : IIEB, 2002. p. 105-19.

- TASTEVIN, C. Le fleuve Jurua. La Geographie, s.l. : s.ed., v.33, n.1, p.1-22; v.33, n.2, p. 141-8, 1920.

- --------. Le fleuve Muru et ses habitants. Croyances et moeurs Kachinauá. La Géographie, s.l. : s.ed., v.43, p.:403-22; v.44, p.14-35, 1925.

- --------. Le haut-Tarauacá. La Géographie, s.l. : s.ed., v.45, p. 34-54; 158-75, 1926.

- --------. Les Kachinawas mangeurs de cadavres. Annales Apostoliques, s.l. : s.ed., n.4, p.147-53, 1925.

- --------. Necrophagia nos Cachinauas”. O Missionário, s.l. : s.ed., v.5, n.1, p.19-20, 1925.

- --------. Quelques considérations sur les indiens du Juruá. Bulletin de la Societé d'Anthropologie de Paris, Paris : Societé d'Anthropologie, ser.6, n. 10, p.144-54, 1919.

- TURNER, Terence (Ed.). Cosmology, values, and inter-ethnic contact in South America. Bennington : Bennington College, 1993. (South American Indian Studies, 2)

- UNIVERSITY MUSEUM OF ARCHAEOLOGY AND ANTHROPOLOGY. The gift of birds : featherwork of native south american peoples. Filadélfia : Univ. of Pennsylvania, 1991.

- Aldeia Kaxinawa encontra saida na psicultura (Selecao Tropical). Dir.: Renato Barbieri. Video cor, VHS, 1996. Prod.: Carmem Figueiredo; MMA.

- A estrada da autonomia. Dir.: Siã Kaxinawá; Vicente Kubrusly. Vídeo cor, S-VHS/VHS, 15 min., 1992. Prod.: CPI-SP.

- Kaxinawá : the real people. Dir.: Siã Kaxinawá. Vídeo cor, S-VHS, 10 min., 1993. Prod.: Interlab.

- Os povos do Tinton-Rene. Dir.: Sia Kaxinawa. Vídeo Cor, VHS, 25 min., 1992. Prod.: Interlab

- Sous les grands arbres. Dir.: Michel Regnier. Filme cor, 16 mm, 58 min., 1991. Prod.: Jean-Marc Garand; ONF.

VIDEOS