Guató

- Self-denomination

- Where they are How many

- MS, MT 419 (Siasi/Sesai, 2014)

- Linguistic family

- Guató

The Guató, considered the Pantanal people par excellence, occupied practically the entire south-western region of what is now Mato Grosso, extending into the state of Mato Grosso do Sul and Bolivia. They were found on the islands and along the shores of the Paraguai river, from the area surrounding Cáceres to the Caracará region, passing through the Gaíba and Uberaba lakes and, to the east, the shores of the São Lourenço river. Within this vast territory, their presence was recorded by travellers and chroniclers since the 16th century.

Between the 1940s and 50s the expulsion of the Guató from their traditional territories became much more intense. Cattle from nearby ranches invaded the indigenous swiddens and fur traders hindered the Guató occupation of Ínsua Island and the surrounding area. Cornered, they migrated to other parts of the Pantanal or moved to the outskirts of towns like Corumbá, Ladário, Aquidauana, Poconé and Cáceres. Few families remained on Ínsua Island. From the 1950s onwards, the Guató were considered extinct by the official indigenist body and were therefore excluded from any assistance policies. It was only in 1976 that missionaries identified Guató Indians living on the periphery of Corumbá. Gradually the group began to reorganize and fight for their ethnic recognition. Today they are the last surviving canoeists from the many indigenous peoples who once occupied the Pantanal lowlands.

Language

Until the 1960s, the Guató language remained classified as an isolated language. In 1970, the linguist Aryon D. Rodrigues published the text Línguas ameríndias proposing for the first time its inclusion in the large and highly hypothetical Macro-Ge linguistic trunk. Years later, the linguist Adair P. Palácio concluded and divulged new studies referring to the thesis put forward by Rodrigues, who himself returned to the topic in Línguas Brasileiras (1986). Before these works, however, the language had been recorded by various chroniclers and ethnographers. Max Schmidt (1942) made the most in-depth record prior to Palácio’s doctoral thesis (1984).

Despite its affiliation to the Macro-Ge trunk, the Guató language does not belong, at least according to the available literature, to any linguistic family pertaining to the trunk, including the Ge family. This situation undoubtedly derives from the absence of more comprehensive studies on the kinship of indigenous languages in Brazil. Nonetheless, taking into account the proposals made by Montserrat (1994), the Guató language can alternatively be considered a linguistic family with a single member, belonging to the Macro-Ge trunk, as shown in the diagram below:

Macro-Ge Trunk >> Guató Family >> Guató Language But while today the Guató family possesses just a sole member, in the past it may well have had other representatives. This assessment takes into account the existence of many indigenous peoples in the Pantanal region prior to colonization. Palácio (1987) provides a useful overview of the Guató language:

“A tonal language (in other words, the high or low tone of a vowel changes the meaning of the words), predominantly agglutinative in terms of word formation, presenting elements of ergativity (the subject markers on the transitive and intransitive verbs are different) and a VSO word order (predominantly verb-subject-object). A quinary (base-5) number system used to the number 20 and a decimal system for higher numbers is one of the features distinguishing it from the majority of Brazilian indigenous languages” (Palácio 1987:75).

Today, the Guató language is practically extinct. Until the start of 2008 there were 5 speakers at the Corumbá settlement, but following the death of Francolina, over 100 years of age, the number fell to four. Another lone speaker of Guató lives in the São Lourenço/Cuiabá region. Despite this sad situation, today attempts are being made to revive the language and encourage its use in the indigenous school.

Name

The word guató is found written for the first time in the Commentaries of the Spaniard Alvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca, written in the first half of the 16th century. From that time on, the word guató was recorded in various forms in the primary textual sources: “guataes, guatás, guathós, guatos, guatòs, goatos, guattos and guatues” (Oliveira 1996).

In 1901, Schmidt recorded the word maguaato, used to denominate a species of moorhen, written by him in a form similar to the ethnic autonym. Because of this, Susnik (1978) claimed that the term guató corresponded to maguaato. Today there are question marks concerning this association since the name that appears in the modern versions of the Commentaries does not seem to have been a self-identification, but a Guarani appellation, just like the other ethnic names of non-Guarani peoples recorded there.

It may well be, for example, that guató is a derivation of guatá, a verb that in Guarani signifies walk, wander, travel and traverse, annotated in this form at the start of the Iberian conquest in order to indicate a canoe people with a high degree of spatial mobility. Over the years, guatá ended up being pronounced and written as guató, incorporated as an ethnic name and autonym in a sociolinguistic context marked by intense interethnic contacts.

Location

The Guató territory, limited exclusively to the Pantanal region, remained relatively unaltered until the mid 19th century when the process of occupying the region of the upper Paraguai river, especially after the Paraguayan War (1864-1870), with the presence of former soldiers, military personnel and farmers. The historiography on the Guató leaves no doubt concerning the extensive area that they once occupied, where the Indians were dispersed into small nuclear families.

In the first half of the 20th century, Monoyer (1905) and Schmidt (1942) attempted to delimit the area occupied by the Guató with greater precision. During 1900, 1901 and 1902, Monoyer, a Frenchman with a knowledge of ethnography, was in Mato Grosso and observed the Guató on the Paraguai and São Lourenço rivers in a marshy area bordering the rivers. In 1901, Schmidt (1942) undertook his first ethnological expedition to the Guató, contacting various families who inhabited the Morraria dos Dourados, the Serra do Amolar, the Canal D. Pedro II (Ínsua Island) and the Gaíba and Uberaba lakes. He also obtained information on the existence of a number of Guató on the Caracará river, a branch of the Paraguai river. Finally he observed that the Guató territory covered a total area of 72,600 square kilometres.

Years later, in 1910, Schmidt made his second expedition to the Guató area. His main objective was to study the Guató who lived on the Caracará river and their respective landfills. In 1928, Schmidt undertook his third and final ethnological expedition to the Guató. He contacted some families who lived on the shores of the Paraguai river from the Descalvado to below the Gaíba lake on the Alegre river, an arm of the Cuiabá river, and on the Canal D. Pedro II (Ínsua Island).

It is notable that most of the accounts, ethnographic descriptions and ethnological studies produced during the 19th century until the first half of the 20th century identify the Guató as the only group to occupy the area between latitudes 16º 30’ to 19º 00’ south and longitudes 56º 30’ to 58º 00’ west.

Hence the area of Guató occupation is situated entirely within the Pantanal region, mostly in Brazilian territory in Mato Grosso and Mato Grosso do Sul, with another portion in Bolivian territory. From this area we can highlight the following expanses of land occupied by this people: the main course of the Paraguai river, the Paraguai-Mirim river, the Alegre, the Caracará region, the São Lourenço river, part of the Cuiabá river, Canal D. Pedro II, Uberaba and Gaíba lakes, Morraria dos Dourados, Serra do Amolar and Ínsua Island. Other large lakes, such as Mandioré, Vermelha and Cáceres, must have also been occupied by the group. These expanses have yet to be investigated by researchers (Oliveira 1996).

Today three Guató nucleuses exist, one of them in Mato Grosso do Sul (Uberaba village, Ínsua Island) and two in Mato Grosso, in the municipalities of Barão de Melgaço and Poconé. The latter include the Baía dos Guató Indigenous Territory (Aterradinho do Bananal and Aterro São Benedito villages) bordering the Perigara and Cuiabá rivers. The third nucleus in Mato Grosso is located close to Cáceres; however, anthropological studies are needed to identify the Guató population resident there and to delimit the territory occupied by them.

Population

The Guató population residing in Mato Grosso do Sul and Mato Grosso in 2008 was 175 and 195, respectively (Funasa 2008).

Despite the various encounters between travellers and chroniclers and the Guató population, the figures recorded on these expeditions always related to just a part of the indigenous population. This resulted from the dispersion of the group throughout the Pantanal region. Prior to the Paraguayan War, Florence, in 1825, calculated the total Guató population in the upper Paraguai region at around 300 people, though he had no access to the population on the Gaíba lake, which, according to reports from nearby residents, was fairly numerous and may have reached 2,000 people.

In 1848, The Director-General of the Indians of the Province of Mato Grosso, Joaquim Alves Ferreira, in a report sent to the Ministry of Imperial Affairs, recorded 500 Guató along the entire upper Paraguai, including Gaíba and Uberaba lakes, the São Lourenço river region and the Paraguai-Mirim river as far as the Descalvado.

In the period after the War, Koslowsky, who remained for three weeks at the Guató nucleus on the upper Paraguai in 1894, encountered 29 Indians in the region. Schmidt, meanwhile, recorded 46 Guató residing on Ínsua Island, also known as Bela Vista do Norte. The probable cause of the collapse in the indigenous population was the Paraguayan War itself, which hit them directly and indirectly. As well as the epidemics that spread through the areas affected by the conflict, especially smallpox, the period saw the start of the more intense phase of non-indigenous occupation of the upper Paraguai, which also collaborated in the expulsion of Indians from their traditional territories and the dispersion of the Guató groups existing in the area.

The table below illustrates the demographic situation of the Guató over the last two centuries.

| Year | Region | Population | Source |

| 1809 | Lake to west of the Paraguai river at 19º 12’ south | 30 | Azara |

| 1825/ 1829 | Upper Paraguai | 300 | Florece |

| 1847 | Paraguai river from mouth of the Uberaba and along the São Lourenço from the mouth of the Cuiabá | 400 | Leverger |

| 1848 | Upper Paraguai, Ínsua, Paraguai-Mirim and São Lourenço | 500 | Ferreira |

| 1894 | Upper Paraguai | 29 | Koslowsky |

| 1901 | Ínsua Island | 46 | Schmidt |

| 1978 | Corumbá, Ínsua Island | 220 | Cruvinel |

| 1984 | Corumbá, Ínsua Island, Bolivia, São Lourenço, Pirigara, Vermelho, Miranda and Campo Grande rivers | 383 | Cardoso |

| 1995 | Ínsua Island, Corumbá, Cáceres, farms and villages from the Pantanal region | 700 | FUNAI/PCBAP |

| 2000 | São Lourenço/Perigara and Cuiabá rivers* | 72 | José da Silva |

| 2008 | Mato Grosso do Sul | 175 | Fusana |

| 2008 | Mato Grosso | 195 | Funasa |

- Not including the Guató living in Poconé and Cuiabá (MT), recorded by Paula & Costa (2000).

Contact history

The first known reference in the literature is by Alvar Nuñes Cabeza de Vaca (1984), who cites the Guató Indians in passages from his Commentaries, on an expedition made to the Mar de Xaraés in the 16th century. Other authors, such as Guzman and Hervas y Azara, cited the Guató in their writings during the same century.

In 1633, the Guató are mentioned among the nations of ‘infidel Indians’ to be subjected to the preaching of the priests of the Company of Jesus. In El Paraguay Catolico, Father Sánchez Labrador (1910) relates that some Mbayá-Guaikuru had told him, in 1767, about the Guató, Indians who cultivated maize, pumpkin, potatoes and cotton in small swiddens planted on ‘landfills’ – terrains artificially raised with shells and sand to prevent inundation during floods.

Felix de Azara (1962) narrated his encounter with some Guató, inhabitants of a lake on the western shore of the Paraguai river. De Azara and other travellers, like Domingo Martinez de Irala (1998), left important historical records about these Indians.

The best images we have of the Guató from the 19th century were produced by Hercules Florence (1948). An assistant draughtsman on the Langsdorff Expedition, he identified the Guató living on the shores of the Paraguai and São Lourenço rivers. Twenty years later, in 1845, another Frenchman, the naturalist Castelnau (1949), visited the same region and complemented the observations made by Florence.

In a document dated 1848 and entitled ‘News of the Indians of Matto Grosso,’ published in the Album Graphico de Matto Grosso (1914), Joaquim Alves Ferreira located the Guató on the Paraguai and São Lourenço rivers and on Gaíba and Uberaba lakes.

The Germans Von Martius and Karl von den Steinen also refer to the Guató in works published in 1867 and 1872, respectively. In 1876 Couto Magalhães, president of the Province of Mato Grosso during the Paraguayan War, recorded the collaboration of the Guató with the Brazilian Army. In 1889, Julio Koslowsky lived for three weeks among the Guató of the upper Paraguai, publishing the results of this expedition in 1896 in the Revista de Museo de la Plata. In 1900, Henry Bolland led a land survey expedition to the regions of the upper Paraguai and its lakes and bays, contributing decisively to the geographic knowledge of the Guató territory.

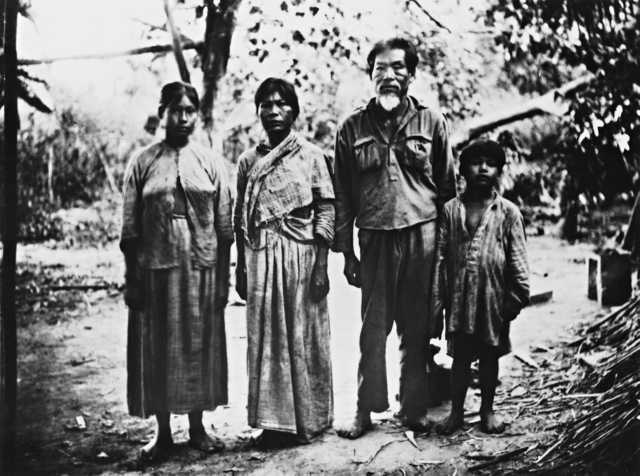

The most complete ethnographic expedition undertaken on the Guató dates from the start of the 20th century. Over the course of three voyages (1901, 1910 and 1928), the German Max Schmidt studied the history and customs of this ethnic group and compiled a vocabulary of the Guató language.

Between the end of the 1940s and the start of the 1950s, a gradual process of expelling the Guató from their traditional territories began. Cattle from nearby ranches invaded the Indians’ swiddens and the skin traders undermined the Guató occupation of Ínsua Island and its surrounding area. Cornered, they migrated to other parts of the Pantanal or moved to the outskirts of towns such as Corumbá and Dourados.

The Guató were considered extinct by the SPI (Indian Protection Service) until the beginning of the 1970s when missionaries from the indigenist team of Corumbá, today Mato Grosso do Sul, identified some members of the population living on the periphery of the town. Through them they were able to locate others living in a portion of their traditional territories and still speaking the Guató language day-to-day. Funai then began the process of identifying the Guató, visiting those living on the São Lourenço/Perigara river in Mato Grosso, and counting a total of twenty-two individuals at this location at the time and 243 people overall. Since the very first reports (from Spanish travellers who explored the upper Paraguai) they were cited as a peaceful group and, at the same time, keen to avoid contact with non-Indians.

The first expedition of the Corumbá Indigenist Missionary Team was to the Guató of the Ínsua Island nucleus in October 1977. The second took place months later, headed by the indigenist technical assistant, Jamiro Batista Arantes. The third and most important from the ethnographic viewpoint up until then was led by Funai anthropologist Noraldino Vieira Cruvinel and lasted ten days (March 1978).

Deterritorialization and reterritorialization of the Guató

Intensification of contacts

At the beginning of the first contacts between Indians and Europeans in the Pantanal, which occurred in the first half of the 16th century, the Guató were already established in the region. Documental analysis enables us to ascertain that along with the Guató there were other canoeiros or canoe peoples in the region, following the example of those who became known in the regional historiography and ethnological literature as Guaxarapo and Payaguá. However, many of these groups, canoe peoples or not, gradually ceased to be mentioned in the historical documentation produced from the second half of the 18th century. This is the case of the Xaray contacted by the Spanish and São Paulo explorers in the first half of the 16th century and the first half of the 18th century respectively.

Since the contacts between Indians and the Spanish were relatively infrequent in the 16th century, at least in the Pantanal region, documentation is fairly scarce.

It was only after the second half of the 16th century, when the Conquistadors’ search for precious metals in the region waned, that contacts with the indigenous peoples became more intense and the latter became the target of encomiendas, that is, the capture of Indians as slave labour in Spanish America.

The existing documentation on the 17th century primarily corresponds to the textual sources produced by priests from the Company of Jesus who worked in missions established to convert the indigenous peoples of the Pantanal. In these sources we find very few references to the Guató.

At the beginning of the 18th century, when bandeirante explorers reached the northern portion of the upper Paraguai basin where the Pantanal is located, discovering gold in the valleys of the Coxipó and Cuiabá rivers, the Guató began to be cited in more documents, this time not Hispanic-American but Luso-Brazilian.

The arrival of the explorers from São Paulo meant that interethnic contacts became more intense. With them came diseases such as smallpox, chickenpox and measles. These diseases were responsible for the diminution of the Guató population and that of other groups inhabiting the region. These new contacts not only initiated a process of depopulation caused by foreign pathogenic agents, but also a gradual process of deterritorialization of the group. But even so the Guató managed to resist the various epidemics and also the attacks of the bandeirantes and even those of enemy indigenous groups.

One of the forms of resistance involved retaining their own social organization, based on nuclear, polygamous families that maintain relations of kinship, alliance and reciprocity. Many of these families comprised kingroups that migrated to less accessible parts of their immense territory, thereby avoiding more long-lasting contacts with non-Indians, especially the violent clashes with the São Paulo explorers.

The expansion of economic frontiers and the plundering of Guató lands

In the 19th century, their territory began to be overrun and occupied by non-Indians, principally to enable expansion of the cattle ranching that was spreading through the region. The government bodies proclaimed the existence of large demographic vacuums in the Pantanal, ignoring the presence of indigenous peoples, in the attempt to attract more farmers to invade the upper Paraguai basin.

At that time, the lands occupied by the Guató had become very attractive for cattle ranching, especially those formed by large native areas of savannah. In these plains, the indigenous landfills probably became the places chosen to build farmhouses and cattle enclosures, for example.

When the war between Paraguay and the Triple Alliance took place between 1864 and 1870, the former south of Mato Grosso, today roughly corresponding to the state of Mato Grosso do Sul, was one of the regions most affected. This region was the first to be invaded by the Paraguayans at the end of 1864. During this episode, various ethnic groups such as the Guató began to have intense contact with Brazilian soldiers, in some cases even fighting and acting as scouts. Following this conflict, the group suffered a new demographic collapse due to the spread of smallpox. This depopulation made it easier to conclude the plundering of indigenous territories to transform them into cattle ranches.

After the end of the war, a new wave of occupation by non-Indians affected the region. This new wave of colonization involved both Brazilian and Paraguayan soldiers who decided to stay rather than return home. Many farmers who had fled from the invading troops also returned to the region. In general, the most important economic activity was cattle farming. The end result was that the Guató once again found their lands being plundered by non-Indians.

Ínsua Island, the last refuge?

The solution found by many indigenous families was to look for refuge in areas that the cattle ranchers would find difficult to access. One of these areas was Ínsua Island, otherwise known as Bela Vista. Other families remained in their territories, resisting in various ways, including working on cattle ranches with the aim, too, of continuing to maintain traditional links with their territory.

However, on the threshold of the 20th century, Ínsua Island also became the target of invasions by new farmers, who let their cattle roam loose to destroy the swiddens planted by indigenous families, as well as many of the natural resources available in the region. At this time, the spatial mobility of the Guató seems to have been reduced, since they no longer possessed an immense territory in which to wander and live according to their uses, customs and traditions. Additionally farming slowly seems to have become the group’s most important economic activity, although activities linked to gathering, hunting and fishing were also very important in terms of family subsistence.

Years later came the prohibition by the Brazilian government of hunting and fishing in the Pantanal, controlled by the now defunct INAMB. This monitoring very often confused the Guató with coureiros – that is, clandestine animal hunters and fur traders. As a result, many Indians ended up imprisoned and punished as criminals since the inspectors were ignorant of the fact that animals such as the cayman and capybara were part of the group’s traditional diet and, in most cases, were not killed for commercial reasons.

On Ínsua Island, many Guató who refused to work for the farmers were threatened with death and expelled from the area. Many were forced to migrate to the towns in search of a better life, being later declared extinct. In addition, towns like Corumbá ended up exerting a certain allure for families that were being expelled from their territories.

Desterritorialization

After 1957, the Guató were declared officially extinct and were ignored by government bodies. Many families went to live on the outskirts of towns like Corumbá, Ladário, Aquidauana, Poconé and Cáceres. Few families remained living on Ínsua Island.

Some families stayed on the island following the intervention by the Army Ministry in order to install a military base in the area, which occurred at the end of the 1950s. Later the Army filed a lawsuit in the Federal Courts demanding ownership of the island. As the farmer based in the region lacked any document proving his ownership of the area, the Federal Courts granted the Army ownership of the locale. However, as the Porto Índio Detachment only occupied part of the island, the other part was leased to the farmer who continued to the cattle ranching begun by his father-in-law, while a few Guató families remained living in the location.

Meanwhile, the Guató continued in their state of extinction until 1976 when the Salesian nun Ada Gambarotto met, in Corumbá, Dona Josefina, daughter of a Guató woman and non-Indian man. Sister Ada Gambarotto, along with the Indigenist Missionary Council and other entities supporting the indigenous cause, proved the existence of the Guató; they organized excursions and discovered that they were greater in number than imagined. This support group was joined by the linguist Adair Pimentel Barbosa, who not only studied the Guató language, but also worked in defence of the group’s rights.

Hence the group began to reorganize, hold meetings and activities to raise the problems experienced by themselves with organized civil society. The Guató began to fight for their ethnic recognition.

Fight for ethnic recognition and reterritorialization

Funai’s actions towards this objective began in 1977 with the official corroboration of the existence of the Guató. Thereafter, a number of expeditions were organized by the official indigenist body and by the Indigenist Missionary Council, culminating in the recognition of the area as land of traditionally occupied by indigenous people.

This then led to the fight for Ínsua Island, given that the location belonged to the Army and, if it was declared an indigenous area, no non-Indians would be able to reside in the area, not even the Army, which alleged that the area was essential to national security since the island is located on the Bolivia-Brazil border.

This legal dispute between the Army Ministry and Funai went on for years until the two sides eventually reached an agreement. The agreement established that the Army would remain in one part of the island and the Guató in the other.

In this way the Guató managed to get back part of the territory traditionally occupied by themselves. This provided the basis for them to reorganize their culture in the context of a complex process of reterritorialization, which is still under way.

Demarcation of the Guató IT

The ‘rediscovery’ of the Guató marked the start of the fight to recover their traditional territory, especially Ínsua Island, situated between the Gaíba and Uberaba bays. Various trips were made by Funai employees to the region inhabited by the Guató with important reports produced in 1977, 1978 and 1984. The latter comprised the Identification and Occupational Survey needed to delimit the Guató Indigenous Area. The report presented data on the entire Pantanal region, including the population inhabiting the towns and cities of Corumbá, Miranda and Campo Grande, the Bolivian region of Campo de Mayo and various localities situated on the Paraguai, Cuiabá, São Lourenço, Vermelho and Pirigara rivers. Those described in the latter location are the same residents of the area located in the Aterro São Benedito village (São Lourenço/Perigara).

The process of identifying the Guató IT had, however, the explicit interest of uniting on Ínsua Island all the family groups spread across the Pantanal, which was why the land ownership of the other known nucleuses was never studied. In effect, some groups were interested in moving to Ínsua Island, especially those that were living without a village in Corumbá (all of them from there) and that were living in poverty on the outskirts of the town. However the identification reports recognize the traditional existence of three distinct local groups among the Guató: a group living on the shores of the upper Paraguai, another inhabiting the region of the Gaíba and Uberaba lakes, and a third residing on the lower São Lourenço river (Schmidt 1942). Historical information indicates that the relationship between these groups was not always friendly.

The ‘intention to cluster’ on Ínsua Island, though necessary to survival (as in the case of the group from the São Lourenço/Perigara and Cuiabá rivers), must be considered within the limits of the relations of kinship and historical and geographical distancing. Hence although the Guató of the São Lourenço/Perigara and Cuiabá rivers are aware of the existence of other Guató in the Caracará region, they never had much contact with them and claim that they have no intention of leaving the area where they live today. The Guató always occupied an extensive tract of Pantanal lands, encompassing the basins of the Paraguai, São Lourenço and Cuiabá rivers.

Social organization

The Guató families live autonomously isolated from one another. Tasks are distributed within the family: men are responsible for making hunting and fishing equipment, the activities of gathering, fishing and hunting, and also for preparing food; women are responsible for making pots and other clay utensils, paddles the canoes and weaving. Woven items were made by both sexes. Children helped their parents in tasks according to their sex. Social organization was patrilinear while residence of newly-weds was patrilocal. In general the Guató were polygamous and each jaguar killed could give the man the right to a wife – in effect, a rite of passage from adolescence to adulthood.

For the Guató, killing jaguars, especially spotted jaguars or mepago, meant defeating an animal much stronger than the man, demonstrating his courage, the taming of the landscape, obtaining hunt trophies and winning prestige within the group, as well as proving himself capable of defending and working to sustain his future family. Hence in some Guató settlements various feline skulls were found on display in the front section of the houses as trophies exhibited to visitors (Oliveira 2002).

Contact between the different local groups (upper Paraguai, São Lourenço and Ínsua Island) basically involved matrimonial alliances forged during the rainy season – the acuri palm fruit chicha festivals – probably on Ínsua Island, considered the centre of the universe and, therefore, a sacred territory. In this way they strengthened the group’s unity and social identity. Also in terms of social organization, the first non-indigenous travellers to the area, as well as referring to the three local groups cited, highlighted the existence of a chiefdom in each of these three units, founded on a line of brothers led by the eldest.

The Guató are typical representatives of the canoe peoples who settled in the floodland areas of the Pantanal region of Mato Grosso. The strategies of occupying this space are related to cultural and ecological factors important to the group’s subsistence, each family depending on its capacity to obtain independently the resources needed for its survival. On the other hand, the biological diversity characteristic of the Guató areas favours the exploration of a range of flora and fauna through hunting, fishing, gathering and agriculture. On this point it is also worth stressing the importance of the landfills for agriculture and for the group’s ethnic identity.

Oliveira identifies the landfills “as the main material remains of the cultural manifestations that occur in the region's floodland areas. They are material witnesses of a type of survival strategy characteristic of the canoeiro groups that once occupied the Pantanal” (1996:150).

Settlements

According to the Guató themselves, they possess three basic types of settlements, all of them related to ecological areas close to the water courses: ‘landfill’ or marrabóró, ‘river shore’ or modidjécum and ‘hillside’ or macaírapó.

The occupation of these settlements is directly related to three factors culturally and ecologically important to the subsistence of this essentially canoe people: 1) seasonality (dry and rainy periods); 2) form of social organization (autonomous families); 3) high spatial mobility (fluvial).

The marrabóró settlements can be found in gallery forest, open fields, thickets or terraces, as well as along the shores of channels, marshes and rivers. The landfills, marrabóró, are the most important for the families and are mainly occupied in the rainy season (floods).

The modidjécum settlements are related to gallery forest vegetation. Normally they are occupied in the dry season and may become partially or completely flooded during the rainy season. In some cases they may correspond archaeologically to landfills.

The macaírapó settlements, on the other hand, despite being more protected from floods, and perhaps more suited to cultivation, are normally occupied during the dry season. This is because during the rainy season, when the fields are flooded, the mobility of the Guató increases, enabling them to explore more easily other areas more suited to subsistence activities. Also during this period people fraternize with other families living in more distant locations, revitalizing the bonds that maintain the group’s unity and social identity.

In the historical documents and ethnological literature there are various sources of information that corroborate the existence of seasonal settlements among the Guató. It becomes clear that this canoe people possessed at least two types of settlement related to the seasonality of the environment: 1) on the shores of rivers during the dry season; 2) in other areas protected from the floods during the rainy season.

Rondon (1949) had frequent contact with the Guató between 1900 and 1906 during the works for the ‘Telegraph Line Commission of the State of Mato Grosso.’ He visited a landfill site partially destroyed by flood water, known as ‘Aterradinho do Bananal,’ located on the right shore of the São Lourenço river, two hundred metres inland, which served as the site of a ranch of the Rio Novo Farm. Despite its fairly imprecise location, Rondon explains that the landfill must have been built by the Guató to protect themselves from the floods. Rondon, though, is not the only source for this kind of information. Florence (1948) reports that long before Rondon, on January 8th 1827, the Langsdorff expedition had reached the landfill in question, also simply known as ‘Bananal’ due to the large number of banana trees planted there.

Rondon defines the Guató landfills as: “an artificial mound, where firm land was scarce in the Pantanal, the Guató made landfills, piling up earth taken from the surrounding area on the chosen spot” (1938:259).

Schmidt’s work provides a more detailed account of the Guató settlements, especially on the marrabóró [landfills]. In 1901, Schmidt ascertained that the marrabóró are similar to sambaquis (shell mounds) as they contain a large number of aquatic molluscs. Later the author discovered various landfill sites along the course of the Caracará river and refers to them as ‘resting places,’ that is, temporary settlements, sometimes for just a single night, used during the rainy season when the Guató abandon the sites occupied during the dry season. He explains that the landfills can be recognized easily since they are elliptical in shape and possess a dense vegetation that stands out in the surrounding environment (Schmidt 1912).

The Guató told Schmidt that the Matschubehe or Matsubehe were responsible for constructing the landfills and also for the banana plantations found there. But they were driven out of the region by the Guató themselves.

The Guató mythology suggests that it was the Tchubé who taught them how to build landfills, but that in exchange the Guató taught them how to use canoes in the Pantanal’s marshes. Consequently, not all the landfills occupied recently by the Guató were built by them, since there are some that were constructed and occupied previously by their allies the Tchubé.

The fact is that the Guató explain the landfills as the result of anthropic action, a collective enterprise coordinated by the chief. Each time that a young Guató man married and lacked a landfill site to occupy, the chief would organize the labour force and supervise the work needed to build a new marrabóró. In recent times there were enough landfills for everyone due to the reduction in the population size.

The landfills were built during the dry season by transporting sediments, including shells from aquatic gastropods and bivalves, in carrying baskets from the lower spots to naturally elevated sites, including alluvial deposits. The shells were important since, as well as increasing the volume, they made the land firmer against the action of the flood water. The Guató explain that most of the shells found in the extracts of the landfills comprise construction material or were deposited there by animals.

To improve the protection against the flood waters, they planted acuris or mudjí (Scheelea phalerata), a palm species of great value to the Guató in terms of subsistence. During occupation of the landfills, normally during the rainy season, people deposit their rubbish there, such as broken pot shards and the bones of various animals consumed as food. These areas may also be used to bury the dead.

Each occupied landfill belongs to a determined family and is known by the name of its patriarch: “landfill of Captain Fernandes,” “landfill of João Quirino,” “landfill of Joaquim,” etc. At the death of the patriarch, ownership of the landfill was transferred to his descendents.

More than one family could sometimes occupy the same landfill for a certain time, usually connected by kinship ties. On the other hand, in cases where the landfill was not being occupied for a while due to the seasonal mobility of the families, it could be temporarily occupied by other families, sometimes for a single night of rest during the course of a long voyage. As a result, occupation of the marrabóró seems to have been virtually continuous.

In sum, the three types of Guató settlements – marrabóró, modidjécum and macaírapó – reflect a seasonable adaptation related to the occupation of floodable areas, which in turn implies, among other factors, better exploitation of particular natural resources during distinct periods, dry season and rainy season.

As for the origin of the landfills, the most plausible explanation is that they really were formed by a set of natural and anthropic factors, as the Guató themselves explain. They attest to a form of environmental management related to the group’s subsistence, settlement patterns and demography. They are mainly occupied during the rainy season.

Habitations

In contrast to other groups, the Guató do not possess a house-village, but habitations that can be classified as provisional shelters and permanent houses, which basically serve to shelter families from climatic factors such as rain.

The provisional shelters and permanent houses may have the same structural design, which can be interpreted as that of the Guató traditional house, called movír (Schmidt 1942).

The habitations were described by various travellers and chroniclers, usually in a simplified form, since the first half of the 19th century. Most of them present similar observations, such as: “poorly built cabins” (Macerata 1843); “rough hut” (Castelnau 1949); “small huts from branches, rapidly built when rain threatens” (Beurepaire-Rohan 1869); “small huts in which they sleep sheltered from the weather” (Leverger 1862); small, low huts built from branches, trunks and palm leaves that are “merely enough to shelter them from the sun and rain” (Ferreira 1993); small cabins made from tree branches and palm leaves, solely to protect themselves from the sun and rain (Moure 1862); very rudimentary habitations, a simple wind-break with a roof of palm leaves on four props (Monoyer 1905).

These temporary shelters involve structures improvised using domestic equipment for domestic use and subsistence. It is less elaborate than the traditional house and smaller in size. It serves for a family to spend a night or rest for a few days. When the Guató change location, this type of shelter is taken down.

The duration of the Guató house depends on the type of wood used, sometimes lasting several years. They are built with wood found at the location of the settlement or nearby. The permanent houses last longer and are built from better quality timber more resistant to the action of the weather, such as aroeira. The covering of acuri palm leaves needs to be replaced more frequently along with the bindings made from various types of vine like imbê. The traditional houses that function as temporary shelters may be made from lower quality of timber.

The number of houses at a given settlement site is related to the size of the family. Evidence of these traditional structures can be detected in archaeological excavations. Following contact with non-indigenous society, the Guató also began to build houses from other types of structures such as wattle-and-daub.

Productive activities

The Guató traditionally lived from fishing, hunting, gathering and agriculture. As they occupied a large area, they managed to obtain their sustenance within the limits of their own lands. All members of the family fished with canoes throughout the entire year. They used bows and arrows and preferred pacu. Hunting was conducted with bows and arrows, traps, slingshots and spears. A wide variety of animals were hunted, the most appreciated being cayman. Gathering was also highly diversified: we can highlight Pantanal rice or wild rice, a native species gathered during the rainy season. Many fruits were relished, especially acuri, waterlily and sitobá (situpá).

The acuri palm was essential since it was exploited in various ways: they extracted chicha, made utensils and ate the fruit. Today it is primarily used to thatch for the Guató houses.

Although many authors in the historical literature categorically affirm that crop cultivation was of little importance as a subsistence activity among the Guató, little is actually known about the agricultural practices of these Indians, meaning there is insufficient data for claiming that it is less important activity than fishing, hunting and gathering. We know that they grew maize, yam, manioc, pumpkin, banana, sugar cane, cotton and tobacco. Crops may be cultivated at the start of the rainy season, before the families temporarily abandon their more fixed settlements with the arrival of the floods.

In terms of contemporary productive activities, the Guató fish, hunt, gather and practice agriculture, though the latter is still incipient. They use shotguns in hunting, but also use bows and arrows in both hunting and fishing. In Mato Grosso, the small area inhabited by them lacked the wood needed to make these items and even less to make canoes, paddles or poles. During the period when they are not fishing, they collect bait, which are stored in deposits (ditches). Women also collect fish bait and help in crop cultivation. Small hotels hire the Guató to pilot boats on the rivers and lake channels of the region formed by the São Lourenço/Perigara, Cuiabá, São Benedito, Mascate, Três Irmãos and Ichuzinho rivers and to collect bait. The Guató state that things become more difficult outside the fishing season. During this period (November to March), the men tend the swiddens, helped by the women, who also look after the house and children, and make pottery.

During the rainy season and floods the main activity is fishing, while agriculture and bait breeding are pursued in the dry season. There are problems with the environmental police, who prohibit fishing and bait breeding outside the fishing season. During the spawning season, fishing has to be confined to the river banks rather than boats and the daily limit is five kilos per person. Honey is gathered for sale, a popular product with tourists. According to the Guató, the best period for this activity is from October onwards during the floods.

The Guató perception of time and space is intimately related to the dry season (June to November) and rainy season (December to May). The lunar cycle is also tracked with 'good moons' for fishing. Winds are also observed, especially during the hunting season.

During the dry season it is easier to collect bait, while hunting is pursued in both dry and rainy seasons. The latter is good for fishing and also for the collecting the abundant ripe fruit (quince, roncador, guava etc.). Signals left or emitted by animals such as the cayman, capybara and quá (a bird species) are interpreted as changes of climate, wind direction and so on – revealing the intense relationship between the Indians and the surrounding environment. Children are made familiar with canoes from a tender age and are frequently found paddling them on the rivers, lakes and channels.

Material culture

Guató material culture basically comprises equipment needed for subsistence (bows, arrows, slingshots, spears, canoes, paddles and poles, stone artefacts, hunting traps, digging sticks, clubs used in fishing) and domestic and work tools: items made from wood, shells, pottery, leather, basketry and weaving. Some of this material culture is produced today, alebit with difficulties, by the group living in Mato Grosso and by the Guató living in Mato Grosso do Sul.

(Giovani José da Silva)

Canoes

The manum canoe is the Guató’s primary means of transport, especially in the rainy season, so much as that men’s legs are fairly undeveloped and bowed, while their upper bodies are noticeably more muscled from paddling.

Moure (1862) relates that families frequently spent the night in their own canoes, fabricated with a rare perfection and strikingly elegant and rapid. Women are responsible for steering the canoe, sat astern. When the whole family is embarked the edge of the canoe is a few centimetres above the water level, though this does not impede the use of bows and arrows to fish and hunt (Florence 1948).

Manufacturing a canoe involves choosing the appropriate wood, which must be soft, light and buoyant, generally cambará. The prow or eopígagá is conical in shape and the stern or hihe is wider to be used as a seat (Schmidt 1942).

In order to help conserve the canoe against the action of water and insects, it should be periodically removed from the water, raised on a wooden platform and then heated by a fire from below, removing the water that penetrates the wood pores. Impermeabilization was achieved by smoking the canoes, simultaneously lubricating them with animal fat generally taken from the capybara or cayman.

The paddles or macum are normally made from caneleira, also known in the region as ‘loro.’ Koslowsly (1895) mentions that the size of the paddles could vary, with the most commonly used possessing pointed blades measuring 70 centimetres in length and 26.5 centimetres in width. Schmidt (1942) mentions large paddles 2.5 metres in length and children’s paddles some 84 centimetres in length.

The pole or madyuada, for its part, is a long pole used to propel the canoe in shallow waters. This item too is made from caneleira.

Pottery

Guató pottery production ceased more or less between 1960 and 1970, depending on the domestic group and the region occupied, a time when the iron and aluminium pans definitively replaced the traditional clay pots. Today only clay pipes are made by a few men and women on Ínsua Island and the lower São Lourenço, a tradition now abandoned by younger people.

Based on ethnographic data and oral information, we can ascertain that the Guató pots, produced exclusively by mothers and daughters throughout the year, were essentially for domestic use, employed to prepare, store and serve solid and liquid foods.

The dark coloured clay was obtained from the shores of rivers and lakes, usually with the help of a paddle blade or another appropriate artefact, deposited in the canoes and taken to the settlements where it was processed outside the houses: the women removed all the impurities from the clay, principally small plant roots, and added ground and sieved shards, sometimes also ground snail and bivalve shells. The clay was kneaded in hides or cayman skins used like a bowl or on plant fibre mats until it acquired the correct uniformity and consistency. Afterwards rolls of clay were made, placed on top of each other and gradually manipulated with the hands until achieving the desired form and size.

The clay was smoothed internally and externally with the use of a bivalve shell or sometimes with a round pebble; the pot was dried in the shade before being fired. The latter process almost always involved a few pots being place together and covered with firewood; the entry of air was controlled to prevent a fall in temperature through the placement of more wood around the fire and on the pots when necessary. When ready, the pottery acquired an initial red colouring and, after being used to prepare foods over a fire gradually acquires a darker colour between grey and black.

Three basic types of pots were traditionally produced: small pots or mudikô´vaí, saucers/plates or muchá/muchá´tum and water pots or matum/matum´ve.

Wicker work

Among the Guató, wicker work is a male activity. They basically use straw from the acuri palm (Scheelea phalerata): for baskets they usually use a chequered pattern, while twill patterns may be used for mats. They make, primarily for domestic use and comfort, sleeping mats made from acuri, called mádaakúts'i, or from southern cattail (Typha domingensis) called miró, as well as fire fans or tiakanatá. To transport cargo they make carrying baskets or mu(n)dá.

The Guató use tucum (Bactris glaucescens) fibre to weave two items for personal comfort: the mosquito fan or mapara and, in more refined form, using the ‘entretorcido’ technique, the mosquito net or mageetó – which was also described by Silva (1930). Both are indispensable to those living in the region due to the quantity of mosquitoes during certain parts of the year. They also use cotton to make mosquito fans or mapara and a ligature for the wrist or mavaerúta.

(Jorge Eremites de Oliveira).

Rituals

Funerary rites

The Guató generally buried their dead in specific locations protected from the floods, but at some distance from the more fixed settlements used during the dry season.

The dead were buried in long trenches on top of a mat. A person’s death was followed simply by the burial and grieving for the loss. Mourning was restricted to women who cut their hair very short after losing a husband. When a child died, the mother would cut her hair by half its length.

(Jorge Eremites de Oliveira)

Festivals

During the festivals people consumed acuri palm wine, also known as chicha, and performed the cururu: they would form a circle and dance for several hours to the sound of the viola de cocho and the gourd rattle (ganzá). Even today the viola de cocho (in the past a string made from howler monkey intestine was used in the viola) and the rattle (ganzá) accompany and animate the Guató festivals.

(Giovani José da Silva)

Notes on the sources

The most complete ethnographic expedition on the Guató was conducted at the start of the 20th century. The German Max Schmidt during three voyages (1901, 1910 and 1928) studied the history and customs of the group and compiled a vocabulary of the Guató language. In addition, he described in detail the objects making up the material culture of these Indians (pottery, wicker work, ropes and fabrics, adornments, musical instruments, weapons and household utensils). His studies were published in books and specialized journals.

Later, the Pole Estanislao Pryjemski, a taxidermist collaborating with the Museu Nacional in Rio de Janeiro, the Manguinhos Institute and the Butantã Institute, lived among the Guató between the 1930s and 1950s. The records left by this researcher have yet to be properly studied. A section of his memoirs are found in an article by the journalist Mário Ramires, published by the journal MS Cultura (1987).

As yet little anthropological research has been conducted on the Guató. However, there are the works produced by the archaeologist Jorge Eremites de Oliveira (1995; 2002), who researched the settlements and subsistence patterns of the Guató and their material culture and subsequently conduced research on the ancient process of indigenous occupation of the Pantanal lowlands. In 2005, the historian Marilene da Silva Ribeiro completed her MA dissertation at the Federal University of Dourados.

In the area of linguistics we can highlight the doctoral thesis by Rosângela Aparecida Ferreira Lima, ‘Letting the Guató speak: some sociolinguistic aspects’ (2002). The most thorough work on the language is the doctoral thesis by the professor of the Federal University of Pernambuco, Adair Pimentel Palácio, who completed the thesis at Campinas State University in 1984.

As well as these sources, there are at least two ongoing projects: one by the researcher Margareth Araújo e Silva on school education among the Guató (doctorate in Education at the Federal University of Mato Grosso do Sul) and another by Adriana Viana Postigo on the phonology of the Guató language (MA in Literature from UFMS).

The most recent anthropological research on the Guató is by Giovani José da Silva who, between 2000 and 2003, was involved in the process of identifying and delimiting the Baía dos Guató IT, conducted by Funai. Currently the researcher is a consultant for the indigenous state school ‘João Quirino de Carvalho’ – Toghopanãa.

Sources of information

- AZANHA, Gilberto. Relatório Guató. Campo Grande: CTI, 1991.

- AZARA, Felix de. Descripción e historia del Paraguay y del Río de la Plata. In: GAIBROIS, Manuel B. (org.). Viajes por America del Sur. Madri: Aguilar, 1962.

- BEAUREPAIRE-ROHAN, Henrique de. Viagem de Cuyabá ao Rio de Janeiro, pelo Paraguay, Corrientes, Rio Grande do Sul e Santa Catarina, em 1846. Revista trimensal de historia e geographia ou Jornal do Instituto Historico e Geographico Brasileiro. 2ª ed. Rio de Janeiro: João Ignacio da Silva, t. 9, p. 376-397, 1869.

- BRASIL. MINISTÉRIO DA JUSTIÇA. PROCESSO FUNAI/ BSB/ 2928/ 85

- BUENO, Francisco A. Pimenta. Memoria justificativa dos trabalhos de que foi encarregado à Província de Matto Grosso segundo as instrucções do Ministério da Agricultura de 27 de maio de 1879. Rio de Janeiro; Typographia Nacional, 1880.

- CABEZA DE VACA. Alvar N. Naufragios y commentarios. 2. ed. Madri: Raycar, 1984.

- CALDAS, João Augusto. Memoria historica sobre os indigenas da Provincia de Matto-Grosso. Rio de Janeiro: Moraes & Filhos, 1887.

- CARDOSO, Paulo Alves. Área Indígena Guató. Brasília, FUNAI, 1985 (relatório de viagem)

- CASTELNAU, Francis. Expedição às regiões centrais da América do Sul. São Paulo: Nacional, 1949.

- FERREIRA, Joaquim A. Noticia sobre os indios de Matto-Grosso dada em officio de 2 de dezembro de 1848 ao ministro e secretário d'Estado dos Negócios do Imperio, pelo director geral dos indios da então Provincia. O Archivo. Revista destinada à vulgarização de documentos geographicos e historicos do Estado de Matto-Grosso. Cuiabá: [s. n.], a. 3, v. 2, 1905. p. 79-96. Edição fac-similar completa 1904-1906. Várzea Grande: Fundação Júlio Campos, 1993. (Coleção Memórias Históricas, 3).

- FLORENCE, Hercules. Viagem fluvial do Tietê ao Amazonas de 1825 a 1829. São Paulo: Melhoramentos, 1948.

- GUZMÁN, Ruy Díaz de. Anales del descubrimiento, población y conquista del río de la Plata. Assunção: Comuneros, 1980.

- IRALA, Domingo Martinez de. Relação de Domingo Martinez de Irala, sobre os descobrimentos que ia fazendo quando foi navegando Rio Paraguai acima por ordem do Governador Cabeza de Vaca, desde o dia 18 de dezembro de 1542. Cuiabá: IHGMT. Publicações Avulsas nº. 12, 1998.

- JOSÉ DA SILVA, Giovani et al. Os Guató. Aquidauana: CEUA/ UFMS, 1998. 8 p. (Trabalho acadêmico não publicado).

- KOSLOWSKY, Julio. KOSLOWSKY, Julio. Tres semanas entre los indios Guatós. Excursión efectuada en 1894. La Plata: Talleres de Publicaciones del Museo, 1895. 30 p. Separata de la Revista del Museo de La Plata. t. 6.

- LABRADOR, José Sánchez. El Paraguay Catolico. Buenos Aires: Coni Hermanos, 1910.

- LEVERGER, Augusto [Barão de Melgaço]. Roteiro da navegação do rio Paraguay desde a foz do rio Sepotuba até o rio S. Lourenço. Revista trimensal do Instituto Histórico, Geographico e Ethnographico do Brasil. Rio de Janeiro: D. Luiz dos Santos, t. 25, p. 287-352, 1862.

- LIMA, Rosângela Aparecida Ferreira. Dando a palavra aos Guatós: alguns aspectos sociolingüísticos. Universidade Estadual Paulista Júlio de Mesquita Filho, 2002. (Tese de doutorado)

- MACERATA, José Maria de. Relatório de frei José Maria de Macerata ao sr. Zefirino Pimentel Moreira Freire, onde descreve as diversas nações de índios que residem em diversos lugares da Província de Mato Grosso (Cuiabá, 5 de dezembro de 1843). Transcrição de Alfredo Sganzerla. Cuiabá, 1843. 9 p. (não publicado).

- MAGALHÃES, José V. C. de. Ensaio de anthropologia: região e raças selvagens. RIHGB, Rio de Janeiro, 1873, pp. 359 - 508.

- MANGOLIN, Olívio. Povos indígenas no Mato Grosso do Sul: viveremos por mais 500 anos. Campo Grande: CIMI, 1993.

- MARTIUS, Carl F. P. von. Beiträge zur Ethnographie und Sprachenkunde Amerika’s zumal Brasiliens. Erlangen: Druck von Junge & Sohn, 1867.

- MONTSERRAT, R. M. F. “Línguas indígenas no Brasil Conteporâneo”. In: Grupioni, L D. (org.). Índios no Brasil. Brasília, MEC, 1994. pp. 93-104.

- MONOYER, E. Les indiens Guatos du Matto-Grosso. Journal de la Société des Américanistes de Paris, Paris, 1905, pp. 155 - 158.

- MOURE, Amédéé. Les indiens de la Province de Mato-Grosso (Brésil). Paris: E. Thunot et Ce, 1862. 56 p.

- OLIVEIRA, Jorge Eremites de. Os argonautas Guató: aportes para o conhecimento dos assentamentos e da subsistência dos grupos que se estabeleceram nas áreas inundáveis do Pantanal Matogrossense. Porto Alegre: PUC-RGS, 1995. (Dissertação de mestrado)

____________. Guató: argonautas do Pantanal. Porto Alegre: EDIPUCRS, 1996. ____________. Da pré-história à história indígena: (re)pensando a arqueologia e os povos canoeiros do Pantanal. Faculdade de filosofia e Ciências Humanas, PUCRGS, Porto Alegre, 2002 (Tese de doutorado em História/ Arqueologia)

- PALÁCIO, Adair Pimentel. Comunicação apresentada na 11ª Reunião da Associação Brasileira de Antropologia, Recife, 1978.

____________. Guató: a língua dos índios canoeiros do rio Paraguai. Tese (Doutorado em Ciências) - Departamento de Lingüística do Instituto de Estudos da Linguagem, Universidade Estadual de Campinas, 1984. 155 p. ____________. Aspects of the morphology of Guató. In: ELSON, Benjamin F. (Ed.). Language in global perspective. Dallas: Sumer Institute of Linguistic, p. 363-371, 1986. ____________. Guató: uma língua redescoberta. Ciência hoje. v. 5, n. 29, p. 74-75, 1987.

- PAULA, Jorge Luiz de, COSTA, Anna Maria R. F. M. Relatório Guató. Cuiabá: AER/ Funai, 2000.

- RAMIRES, Mário. A volta do Maguató: o frango d’água pantaneiro. MS Cultura, Campo Grande, mar. 1987, pp. 37 – 46.

- RODRIGUES, Aryon Dall’Igna. Línguas brasileiras: para o conhecimento das línguas indígenas. São Paulo: Loyola, 1986.

- RONDON, Frederico. Na Rondônia ocidental. São Paulo: Nacional, 1938.

- RONDON, Cândido Mariano da S. Relatório dos trabalhos realizados de 1900-1906 pela Comissão de Linhas Telegráficas do Estado de Mato-Grosso, apresentadas às autoridades do Ministério da Guerra. Rio de Janeiro: Departamento de Imprensa Nacional, 1949. 333 p.

- SCHMIDT, Max. Die Guató. Verhandlungen der Berliner Anthropologischen Gesellschaft. Sitzung vom 15 Feb. 1902, p. 77-89, 1902.

____________. Hallazgos prehistóricos en Matto-Grosso. Revista de la Sociedad Científica del Paraguay. Asunción: Imprenta Guarani, n. 1, t. 5, p. 27-62, 1940. ______. Nuevos hallazgos de grabados rupestres en Matto Grosso. Revista de la Sociedad Científica del Paraguay. Asunción: Imprenta Guarani, n. 1, t. 5, p. 63-71, 1940. ____________. Estudos de etnologia brasileira. Peripécias de uma viagem entre 1900 e 1901; seus 208 resultados etnológicos. Tradução de Catharina Baratz Cannabrava. São Paulo: Companhia Editora Nacional, 1942. 393 p. (Coleção Brasiliana - Série 5ª, 5). ____________. Resultados de mi tercera expedición a los Guatos efectuada en el año de 1928. Revista de la Sociedad Científica del Paraguay. Asunción: La Comena, t. 5, n. 6, p. 41-75, 1942. ____________. Anotaciones sobre las plantas de cultivo y los metodos de agricultura de los Indígenas sudamericanos. Revista do Museu Paulista. São Paulo: Museu Paulista, Nueva Serie, v. 5, p. 239-252, 1951.

- SILVA, Antonio Carlos Simoens da. Cartas Mattogrossenses (Viagens do Rio de Janeiro a Porto Esperança – Vida agrária e pastoril – Caça e pesca – População indígena do Estado – Cidade de Cuyabá – Industrias extractivas (herva – mate) – Curiosidades e peculiaridades do Estado.). Rio de Janeiro: Imprensa Nacional, 1927.

____________. Une moustiquaire des indiens Guatós (Brésil). Annals of the XXIII International Congress of Americanistes. New York: [s.n.?], Session 23, 1930. 4 p. Separata.

- STEINEN, Karl von den. Entre os aborígenes do Brasil central. São Paulo: Departamento de Cultura, 1940.

- SUSNIK, Branislava. Dimensiones migratorias y pautas culturales de los pueblos del Gran Chaco y de su periferia (enfoque etnológico). Suplemento antropológico. Asunción: Universidad Católica, n. 1-2, v. 7, p. 85-107, 1972.

____________. Etnologia del Chaco Boreal y su periferia (siglos XVI y XVIII). Asunción: Museo Etnográfico “Andrés Barbero”, 1978, 156 p. (Serie Los Aborígenes del Paraguay, n. 1). ____________. Classificación de las poblaciones indígenas del area chaqueña. Manual de etnografía paraguaya. Asunción: Museo Etnográfico “Andrés Barbero”, p. 209-212, 1961.

- WILSON, James. Guato words list. Brasília: SIL, 1959.