Gavião Parkatêjê

- Self-denomination

- Parkatejê

- Where they are How many

- PA 646 (Siasi/Sesai, 2014)

- Linguistic family

- Jê

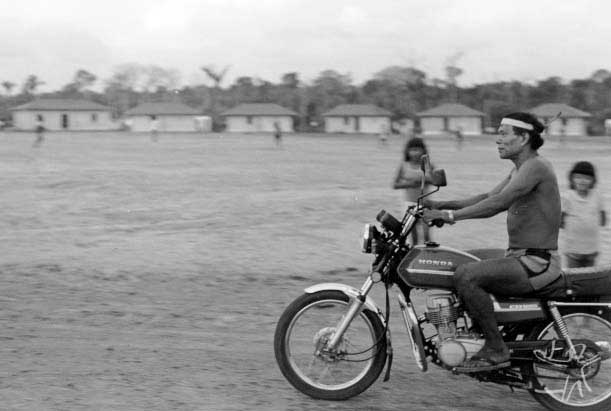

After a traumatic phase of ‘pacification’ taking place in the 1970s, in which more than 70% of the population was lost, the Gavião survived the population crisis and reconstructed their way of life. The conception of Kaikoturé village, built in 1984, translates the Parkatêjê’s project for the future: reproducing the traditional circular layout of Timbira villages, it possesses brick houses linked to water, electricity and drainage systems.

Name

The name ‘Gavião’ (‘Hawk’) was attributed to various Timbira groups by 19th century travellers impressed by their bellicose character. Among those so called, Curt Nimuendajú qualified those who lived in the Tocantins river basin as ‘western,’ ‘of the west’ or ‘of the forest’, so as to distinguish them from the Pukôbjê and Krinkatí of the upper Pindaré in Maranhão State, peoples also known by the same designation.

In the first half of the 20th century, the ‘Western Gavião’ were distributed in three local groupings, named by themselves in accordance with the position they occupied in the Tocantins basin. One of these was called Parkatêjê (where par means foot, down-river; katê means owner; and jê means people), ‘the down-river people.’ Another grouping was called Kyikatêjê (where kyi means head), ‘the up-river people:’ due to warfare between the two groups at the start of the 20th century, the latter took refuge up-river of the Tocantins, in Maranhão State; as a result, the Kyikatêjê are also designated as the ‘Maranhão group’ (to avoid confusion with the Pukôbjê and Krinkatí). The third grouping, which became known as the ‘Mountain group’ due to their self-designation Akrãtikatêjê (where akrãti means mountain), occupied the headwaters of the Capim river.

Although today they are all reunited, the distinction between the three groupings remains marked. A self-designation common to all does exist, though, as the signpost at the entry to the new village indicates: the ‘Comunidade Indígena Parkatêjê’ (‘Parkatêjê Indigenous Community’), a name actually created by the Gavião as an expression of the autonomy gained by them in 1976, and an indication of the new developments taking place in their interethnic relationships.

Language

The Gavião speak a dialect of the Eastern Timbira language, belonging to the Gê family.

From 1981 onwards, the use of Portuguese spread in an intense form with the regular functioning of the Funai Post school and with the intensification of relations with various segments of Brazilian national society – a change occurring precisely at a day-to-day level, including among children and adolescents.

On the other hand, the resumption of long-term ceremonial cycles accentuated the use of the original language on ritual occasions: during songs, speeches, etc.

Location

The Gavião live in the Mãe Maria Indigenous Territory, located in the municipality of Bom Jesus do Tocantins in the south-east of Pará State. Situated within a terra firme zone of tropical rainforest, it is bordered by the Flecheiras and Jacundá creeks, affluents of the right bank of the middle Tocantins river.

The Mãe Maria stream, whose source lies within the indigenous territory, supplied the name for the Post set up by the SPI in 1964 by the side of a narrow track that, three years later, became one of the first state highways in the region: the PA-70 (as it became known locally, although it has been the PA-332 since 1982). This highway was the first link between the municipality of Marabá and the Belém-Brasília road before construction of the Transamazonian highway. In 1967 it traversed the immense Brazil nut tree forest making up the Gavião territory along its entire length – about 22 km running north-south.

In 1977, the south-western limit of the Indigenous Territory was affected by the construction of another highway, the PA-150, which sets out from Morada Nova – km 12 of the PA-70 – in the direction of Castanhal, a municipality close to Belém. The construction of these two highways accelerated the effective disordered occupation of this section of eastern Amazonia, encouraging the systematic invasion of Gavião land both by settlers and by infrastructural works for the state projects under development in the region.

Later, the indigenous territory was cut still further by Eletronorte’s power transmission line, originating at the Tucuruí Hydroelectric Plant, and by the Carajás Railway in 1982. Some 40 km from the city of Marabá, the region’s main urban nucleus, and only 30 km from the settlement of São Félix, the Gavião live in Kaikoturé village – one of the names of the leader of the group, Krohokrenhum – which was inaugurated in July 1984. It is situated about one kilometre from the PA-70 highway.

Population

From 1975 onwards, twenty-five years after the ‘pacification’ phase during which they lost 70% of their population, the Gavião began to exhibit a clear trend towards demographic growth. The process of recuperation involved solutions such as the re-integration of Gavião men and women who had been raised among whites or other indigenous peoples, marriage with women from the regional non-Indian population, the search for wives among the Pukôbjê, and the incorporation of families or individuals from non-Timbira indigenous ethnic groups and even non-Indians, in a conscious policy of restoring the size of the population.

In 1985, the Gavião population numbered 176 people; however, also living in the Kaikoturé village were another 16 Guarani, a Ka’apor man, a Tembé man and 17 Kupên (‘civilized people’). The group was primarily made up of children and youths (from 0 to 20 years old), who made up more than 60% of the total. In global terms, a pronounced imbalance between the sexes could be observed in favour of the men, though this was beginning to be corrected by a higher birth rate among female infants.

The Gavião Parkatêjê overcame the population crisis and today present a population of 338 individuals, including many children and youths (Jane Beltrão 1998).

History of contact

Based on 19th century travellers’ reports, Nimuendajú gives the precise location of the Gavião as the headwaters of the Jacundá and Moju rivers, where indeed they maintained their large villages until the 1960s. The contacts and relations established by the Gavião Indians in this area with the expanding frontiers of Brazilian society passed through distinct phases, corresponding to the exploration of economic resources on the Tocantins river. The first phase was made up of fleeting and peaceful visual contacts between Indians and whites when the pioneers used the shores of the river as resting places. This lasted until the end of the 19th century, during which period there was no need nor motivation to penetrate deeper into the forest.

At the start of the 20th century, forest extractavism (rubber, copaíba oil and finally Brazil nuts) modified the socio-economic infrastructure of the middle Tocantins and the Burgo do ltacaiúnas, which eventually became the town of Marabá. The regional population’s concern to neutralize the Gavião dates in particular from the start of Brazil nut exploration – around 1920 – when the forests on the right shore of the Tocantins river were penetrated in order to locate Brazil nut trees.

Gavião oral traditions refer to this period, marked by the intensification of relations with ‘civilized folk,’ the kupên. According to Krohokrenhum’s account, the Gavião started to ‘accustom’ themselves to the presence of the whites in their territory. The relations at first seemed to be friendly as they obtained industrialized goods from the kupên, such as machetes and axes. Soon, though, violent episodes occurred, with deaths on both sides, especially after the killing of one of the indigenous chiefs by Brazil nut harvesters on the lower Tauri river. The Gavião retaliated and killed three harvesters, in addition to burning down their huts (Folha do Norte 25-03-38). Thus, a cycle of revenge killings marked the intensification of relations with non-Indians.

The conflicts between the Gavião and the Brazil nut harvesters escalated in scale as the product assumed more importance in the regional economy. These armed confrontations took place along a 180 km stretch on the right shore of the Tocantins river, including lands in the contemporary municipalities of Tucuruí, Itupiranga, Marabá and São João do Araguaia. During this period of the 1930s and 1940s, the Gavião were accused of practising ‘great acts of savagery,’ and in Marabá, the region’s main commercial centre, local politicians, merchants and Brazil nut plantation owners organized expeditions to exterminate the Gavião.

It was only in 1937 that the SPI set up a Post on the Ipixuna river with the aim of ‘attracting’ the Gavião. Almost immediately, various Indians started to visit the Post in order to receive tools and other ‘gifts’. But on one of these visits, “they found the Post lacking tools and above all manioc flour, upon which they showed their discontent and killed one of the workers with a number of arrow shots. They ceased frequenting the Post, having established peaceful contacts at other points on the Tocantins, including at a place called Ambauá, near to Tucuruí" (Arnaud 1975: 37).

In 1945, the SPI changed location and set up a post in Ambauá, resuming its attraction work. The different local groupings into which the Gavião were then divided varied in the way they visited the area: some included violent incursions, which were widely reported in the national press in alarmist fashion between 1948 and 1951 (such as, for example, the material published in the Estado do Pará on 29-01-48 and in the Cruzeiro of 31-03-51; see Arnaud 1984: 12-13).

“The belligerent ethos of the Gavião, however, also regulated norms of territorial expansion of the various groups within the same system of social relations. Not infrequently, internal conflicts were motivated by thefts of products from swiddens, accusations of sorcery or the abduction of women” (Arnaud 1984). It was in this context at the start of the 20th century that the splits occurred which generated the three local groupings of the Gavião previously mentioned.

The start of the 1950s was marked by the decisive rupture of a traditional order: the operation of the system of social organization was fatally weakened by the break up of common territories, the arrival of new diseases and consequent depopulation. The complete absence of conditions for resistance by the local groupings into which the Gavião had segmented made ‘surrender’ their only chance for survival, seeking contact with the kupên – the ‘civilized folk’ or the ‘Christians.’

Following the death of the old Gavião chief – called ‘Indiuma’ by the regional population – who had rejected any contact with the kupên throughout his life, Krohokrenhum’s leadership during this period over the few members of the Cocal group, a Parkatêjê village, began to take hold. His career as a leader and singer is related to his personal courage and that of his followers in approaching the non-Indians.

The decisive contacts with the Cocal group took place in 1956, through an expedition organized by the Dominican Fra Gil Gomes Leitão and by a lieutenant from the reserve army in the service of the SPI. With few resources, they procured an encounter with the Gavião in order to prevent the punitive expeditions organized with the support of local politicians from attaining their objective: extermination of the Indians so as to enable the exploration of the Brazil nut trees on which they had fixed their sights.

After this contact, many people from the Cocal group went to the town of ltupiranga, where they stayed for about four months, making their living by performing small tasks for the local population – filling pots of water, collecting firewood or providing public displays of their archery skills – in exchange for clothing and food. The outcome was an even more drastic depopulation when they later returned to the village and spread epidemics of influenza and measles.

Fascinated by the town, the group had abandoned their old village to take refuge in a location lacking any systematic assistance from the SPI: their means of subsistence were precarious and the lands were already occupied by the regional population. According to a manuscript by Fra José, a Dominican who visited the Gavião, the area had been acquired by a deputy from Belém.

They opened small swiddens and began to adopt personal names in Portuguese, which – like the use of clothing – made up part of a specific system of communication and interaction with the kupên who supplied them with industrialized goods. The SPI agents encouraged the Indians to collect Brazil nuts in exchange for knives, ammunition and food items. The forest of Brazil nut trees where they had located – leased by a ‘Seu Benedito’ who ‘allowed’ them to settle there, thereby becoming a ‘friend’ of the Gavião – started to be exploited individually by them according to Da Matta (1967: 115). The produce was sold in Itupiranga and the transportation sponsored by a functionary from the municipality’s local council who came to work as an SPI agent among the group. The Gavião were thus initiated into the mechanics of buying and selling during this period at the onset of the 1960s.

In contrast to the Cocal group, the ‘Mountain group’ went to settle at the end of the 1960s at the site known as Ambauá, where an SPI Post (and pastures) had already existed since the beginning of the 1940s. The systematic contacts with the inhabitants of Tucuruí, situated half an hour by motor boat from the Post headquarters, led to the Gavião ceasing to be seen as ‘plunderers’ and starting to supply the local market with animal game, fish and Brazil nuts. For the town dwellers they had become ‘believers.’ Indeed, from 1964, members of the New Tribes Mission of Brazil had installed themselves on the ‘Mountain.’

Concentration in Mãe Maria

In 1943 a tract of land had been conceded to the Gavião Indians by decree of the then Federal Governor of Pará State. According to Cotrim, during this period the Gavião used to disembark on a beach on the Tocantins river in front of the Mãe Maria Brazil nut forest and fraternize with the administrator. The latter deduced that the Indians must inhabit the headwaters of the Mãe Maria creek and undertook to claim this land for them, an area located between the Flecheiras and Jacundá rivers, one league from the shore of the Tocantins, a zone where he (as administrator) harvested Brazil nuts (Soares 1983).

This area came to be leased to third parties by the SPI from 1947 onwards for a sum considered ‘derisory,’ but in 1965 the SPI began to receive proposals for new leases at extremely high prices. With the opening of the PA-70 in 1964 the area stirred much interest and dozens of settlers moved into the indigenous area. Observing that the SPI functionaries were unable to contain the area’s occupation, Antonio Cotrim decided to convince 28 Gavião people in Itupiranga to move to live there.

The expectations of the SPI agents for “inaugurating the economic life” of the Post were linked to the efficiency of the Gavião’s action in dispelling the Brazil nut harvesters who had settled there. The stereotypes then prevalent concerning the Gavião were utilized and reinforced in the expeditions which concentrated on a particular section of the road, between the Flecheiras and Jacundá rivers, with precise objectives.

At the end of the 1960s, the penetration by settlers and land dealers, facilitated by the opening of the PA-70 highway and the rapid advance of cattle ranching, ended up confining under considerable pressure the group that had taken refuge in the Maranhão, in a place that became known as Igarapé dos Frades, in Saranzal, close to Imperatriz (Arnaud 1975: 72-76). Towards the end of 1968, the area where the ‘Mountain group’ was found – close to the PA-70, but 150 km from Mãe Maria – was interdicted by decree (nº 63.515 of 31-10-68), a measure that failed to be respected by the pioneer population. The Gavião reacted violently, leading to deaths on both sides, which provoked widespread panic throughout the region (0 Estado de S. Paulo 30-05-72).

In order to create definitive contact with the group, a section stretching several kilometres along the PA-70 was interdicted by the Army, Funai, the Pará State Government and the Federal Police. In this way, the Attraction Front, headed by Cotrim and aided during the final stage of attraction by interpreters from the Mountain group, established contacts before the end of 1968. Faced with the potential ‘massacre’ to which the group was exposed in this locality, Funai negotiated their transfer to Mãe Maria. Exploiting a sum of money supposedly covering the expenses of resettling the group, the area was handed over to an regional company specialized in land claims. Today, this area, known as ‘Cinelândia,’ is crossed by the Carajás railway and is occupied by around 15,000 families of settlers in countless small communities.

Impelled by the government policy of gradual occupation of the so-called ‘empty spaces’ of Amazonia, the start of the 1970s saw the initial developments of two large construction projects: the Transamazonian highway and the Tucuruí Hydroelectric Plant, the latter intended to accompany the exploration of minerals in the Serra de Carajás. Funai therefore decided to remove the Mountain group to the Mãe Maria Indigenous Park, where six unmarried boys had arrived in 1971. The following year, construction of the Tucuruí Hydroelectric Plant dam began, precisely in the area conceded to the Gavião in 1945.

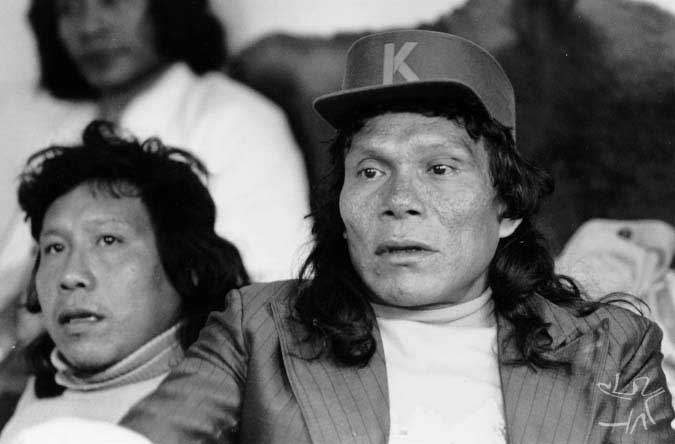

The contact leader

Krohokrenhum was involved in the various phases of contact with the kupên from their outset, having been the principle motivational force behind the exchanges. He took the lead throughout the entire process and at a certain point came to believe that his people were really close to the end. Exercising his leadership in fact amounted to deciding for the whole group: from the transference to Mãe Maria, to the submission to Brazil nut harvesting, to the growing discontentment and definitive rupture of this system of labour.

During this post-contact period, his prestige grew as a leader of the Gavião, who little by little were assembling in a single village. As his peers recognize, Krohokrenhum is a great singer and skilled archer, and has been the main catalyst behind resuming the ceremonial cycles in an intensive fashion from 1976 onwards. He is the paramount mediator in the event of internal conflicts or in the face of external threats; in any situation which could place the group’s harmony at risk. Guardian of the integrity of their territory, still heavily under threat from the intense process of occupation in the Marabá region, Krohokrenhum is well aware that the confrontation with non-Indians is a never-ending struggle.

Krohokrenhum is reluctant to leave the territory of the ‘Parkatêjê Indigenous Community.’ He usually sends emissaries and some people among the Gavião specialize in ‘external affairs’ (commerce, banks, Funai, Brazil nut exporters, etc.) in the neighbouring settlements or in Marabá, Belém and Brasília. Krohokrenhum does occasionally travel, but for a long time now he has insisted that important negotiations concerning the fate of the Gavião and involving representatives of Federal agencies should take place in the village itself.

Back in 1977, he gained notoriety for his resounding refusal of an invitation from the Home Minister, Rangel Reis, to appear in Brasília at the act of signing a bank loan for the Brazil nut harvest. The same style continued in later negotiations with representatives of Eletronorte and CVRD which ended up in large indemnities. Krohokrenhum is fully aware of the reputation the Gavião have acquired in the region and wider Brazil, “the Indians who became rich with indemnity payments.” He is unhappy with most of the versions circulated by the press concerning the changes taking place in the life of the village.

The firmness of his leadership and his prestige as chief of the Gavião is undeniable, despite sporadic crises in his authority. In July of 1985, for example, in a dramatic and unusual gesture, with great repercussions in the village’s life, Krohokrenhum publicly broke his gourd rattle and his bow and ordered destroyed the logs that were to be used in a ‘race,’ after a group of youths – recently arrived from ‘commerce’ – preferred to play football in the village patio instead of taking part in a ritual involving songs and dances. Speaking little with the kupên, but the author of long and frequent discourses on the village patio, Krohokrenhum has been the guiding force behind the Gavião’s wide-ranging forms of resistance.

From Funai's Brazil nuts to Gavião's Brazil nuts

The transference of all the local groups to the Mãe Maria Indigenous Territory allowed Funai to implant the necessary work force for developing an activity that ended up making this post the largest producer of Brazil nuts at the start of the 1970s. The system of economic exploration to which the Gavião were submitted as a labour force of harvesters lasted ten years from 1966 to 1976. During this period, the Gavião recovered in demographic terms as a result of the medical care provided by Funai.

Over the years, the manipulation of the distribution of income from the Brazil nut harvests through the system of paying ‘commissions’ to the leaders by the local Funai agents eventually generated widespread dissatisfaction among the Gavião. At the same time, though, the compulsory nature of the Brazil nut work during six months of the year and the intense physical effort required in order to obtain goods that had now become indispensable, prevented the realization of traditional activities, such as long-term ceremonies.

Krohokrenhum decided to visit the Belém Delegacy personally so as to resolve the question of the ‘commission’ paid by Funai as remuneration for the Gavião’s work in the Brazil nut harvesting. In a vehement dialogue with the Gavião leader, the then regional delegate claimed that from that point on he would cease to market the Mão Maria Brazil nuts produce, since the Gavião had revealed themselves to be intolerant of the system ‘accepted’ at the other indigenous posts producing Brazil nuts.

In the same year, the anthropologist Iara Ferraz was undertaking preliminary surveys for the implementation of the Emergency Project for the Co-ordination of the Brazil Nut Harvest by the Gavião of Mãe Maria. She debated with the Gavião the concrete possibility of marketing the production directly with exporters without the mediation of Funai.

Despite the initial administrative and political obstructions coming from the Delegacy and the DGPC in Brasilia (delay in the issue of an initial allowance and inadequate supplies), the end of the 1976 harvest represented the conquest of their autonomy for the Gavião. Assuming the role of producers, the Gavião succeeded in reaffirming themselves in terms of the regional population, becoming both admired and respected. At the same time, they re-assumed an attitude of fully affirming an ethnic identity that had been under threat. In order to express the difference in relation to the “time when Funai was boss,” the Gavião assumed the collective and institutionalized self-designation ‘Parkatêjê Indigenous Community,’ while simultaneously undertaking the institution of the ‘canteen’ schema for redistributing merchandise at a larger scale.

The transformations taking place also extended to the definitive rupture with the MNTB agents who had attached themselves to the ‘Maranhão group’ since 1971, as well as the complete modification of relations with Funai workers. In congruence with the model of occupation and expansion occurring in the region, the Gavião were visibly attracted to a series of ‘deals’ – later named ‘community projects’ – which appeared lucrative to them and which would increase the Community’s fund of resources.

Once the emphasis of this enterprise was on direct marketing with exporters, the Gavião started to use the traditional means of market speculation in both Marabá and Belém, a practice common to regional producers. The ‘buying and selling contracts’ for Brazil nut lots were signed by two representatives of the ‘Parkatêjê Indigenous Community.’

The ‘Gavião’s Brazil nuts,’ as distinct from ‘Funai’s Brazil nuts,’ were sold in Belém – the production shipped there in lorries hired by the community – due to a few advantages such as a higher price and correction of the standard-measure. In Marabá, this measure is supplemented by the so-called ‘hectolitre head,’ about 10 litres, in order to compensate the buyer for loss or damage to the product before it reaches their deposits in Belém.

As a consequence, the Gavião established personal and direct relationships with certain sections of Brazilian national society who they had not known until then, groups represented above all by exporters and bank agents. Financial control of the harvest and any other commercial operations was effected in 1876, through cash registers maintained by two members of the ‘Mountain’ group, both Krohokrenhum’s assistants. This work was accompanied by the Gavião chief and aided by the head of the Post. These two representatives signed contracts and administered the bank accounts in name of the ‘Parkatêjê Indigenous Community,’ as indicated on the new cheque books which quickly substituted the old Post printed forms.

Eletronorte and the Companhia Vale do Rio Doce

Social organization

The strengthening of Gavião identity from 1976 onwards was expressed both through the new relations established with whites and through the re-conjoining of the productive cycles with the long term ceremonial cycles. The reconfiguration of Gavião society was also effected through the re-arrangement of the links between the previously separate local groupings, which in turn used to present subdivisions into smaller sections. It was in this context that construction of the large village reuniting all the western Gavião in the Mãe Maria Indigenous Territory took place.

The new village, named Kaikoturé, is made up by 33 houses arranged in a circle (which has a diameter of about 200 metres), the traditional format of Timbira villages re-adopted by the Gavião. A wide path circles the village in front of the houses, while various radial paths lead to the central patio where all ceremonial activities are performed.

The uxorilocal residence pattern – the husband goes to live in the house of his wife who remains in her mother’s house – was abandoned following the depopulation occurring after contact. This practice was later resumed in the old village of Mãe Maria, assembled in residential segments formed by nuclear families interlinked on the maternal side. In general, groups of real or classificatory sisters remain spatially close – living in the same segment – after marrying.

The houses of the new village were built using brick with blue painted walls and with doors and windows painted white. They are covered with clay roofing tiles. All the houses are connected to water, electricity and drainage systems.

Krohokrenhum’s house has two floors. On the ground floor there is a veranda, a hall for important meetings, a TV room (where many people meet at night, mostly youngsters). On the first floor: a veranda, a small room and three bedrooms for Krohokrenhum’s family. At the back of his house there is another brick building with the kitchen and a large veranda where meals are taken. The daily morning meetings involving all the men take place there.

The adoption of the ‘modern’ regional style was the outcome of multiple pressures exerted by hire firms, local sellers of industrialized construction material and tutelary agents, especially after the Gavião had received indemnization from Eletronorte in 1980, when construction of the power line forced them to move. However, the brick buildings, constructed as improvements for the Mãe Maria IP, comprised the ‘model’ for houses ‘good to live in’ for the Funai agents over the following years, as promised to the Gavião from the time when they had begun to be transferred to the latter locality.

Currently behind each house – whose internal spatial occupation does not exactly correspond to the divisions constructed for a room, bedrooms, kitchen and bathroom – there is a small shack made from wood or babassu leaves, with only a small part closed by walls, which is very similar to the traditional Timbira house. People spend a large part of the day there: it is a place for cooking and resting, using the inside of the brick house only for sleeping at night. In fact, many of the Gavião, particularly the elders, became unhappy with the way the works were conducted in the village and complained especially about the heat and the noise in the new brick houses.

The non-Indians who have joined the Gavião currently live beside the new village, in a temporary settlement built from babassu palm, planks and asbestos, where all the members of the group stayed for a year (1980), waiting for the end of construction of the new village and while the high tension towers were being built at the site of the old village.

Despite the accentuated demographic imbalance, the process of population recovery allowed the Gavião to re-establish the operation of an age set system that centres precisely on the more numerous male population. This system divides into children, adolescents or ‘bachelors,’ adults ‘married without children’ and adults ‘married with children.’ Each one of these sets is associated with particular levels of participation and prestige.

Despite making little use of their native language in the daily life of the village, the Gavião reverted to putting into practice the naming system and the relations engendered through it, with the performance of the long term ceremonial cycles, as one of the mechanisms involved in the re-affirmation of the group’s ethnic identity.

With the reforms occurring from 1976 onwards, an intense revival of the long term ceremonial cycles took place, until then impeded by the agents of the Post. The naming system thereby regained its importance as a functioning classificatory system, since it is responsible for the recruitment of the integrants of the basic ritual units into which the whole society divides during the ceremonies.

It seems that the mother’s brother or father’s sister, whether real or classificatory, are the preferential transmitters of male and female names respectively. However, due to the emptying of the ideal categories, it is nowadays possible to observe re-configurations in the parents’ choice of those who will give names to their children, above all in response to the expansion of a network of intragroup relations.

Each individual receives two names (or more) of which only one is used. For both men and women, the transmission of names imposes responsibilities on them to act as mentors for those who receive the names, guiding them in the ceremonies, teaching them songs and log racing techniques, as well as myths. Parents may transmit the names of their deceased close kin to their own children. This amounts to a way of preserving the names and the ‘place’ of the dead. Each person tends to call members of the Community – except their closest consanguine relatives – by the same kinship terms used for them by the individual who gave the person his or her name, as well as adopting their formal friends. A child adopts all the ceremonial affiliations of the person who gave him or her their name. In other words, the name giver and receiver are socially identical.

Among formal friends relations are marked above all by avoidance, which also applies between son/daughter-in-law and father/mother-in-law.

Revival of the rituals

Within the re-configuration instigated by the Gavião, returning to ‘playing about’ – as they describe the rituals – meant recuperating institutions and rules essential to the operation of their system of social organization. In 1976, the ‘new maize festival’ – realized from the end of January, exactly at the start of the Brazil nut harvest – was marked with great enthusiasm and euphoria by everyone, above all emphasizing the re-configuration that had been set in motion.

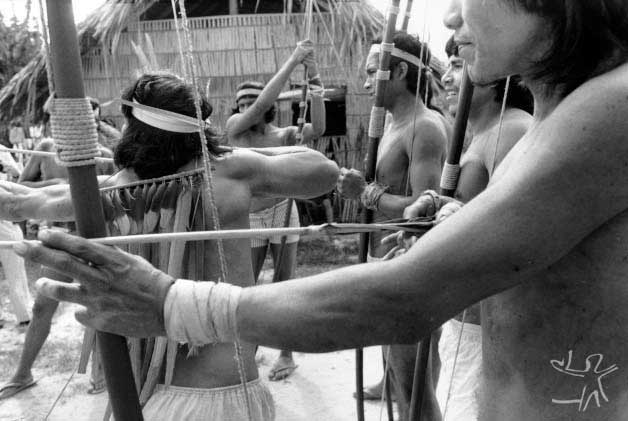

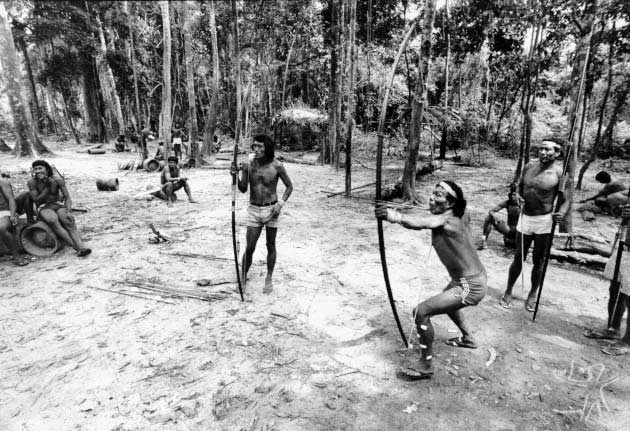

Gavião rituals are directly occupied with the relations between persons and groups through the use of a symbolic schema: the division into moieties. The entire group is segmented according to ceremonial moieties, Pàn (Macaw) and Hàk (Hawk), who dispute the traditional log races and archery contests. Another division into the Fish, Otter and Stingray sections comes into play during the performance of another ceremonial cycle.

It is not just the moieties and other sections that take part in the rituals: it is also possible to note oppositions between kin and affines, between formal friends, between men and women, or between different age sets. Football matches, taking place frequently on the village’s ceremonial patio itself, are always divided between young and mature men.

Some rituals last several months, with opening and closing periods. Linked to all the rites, the log races started to be held with considerable frequency once more: these are basically disputed between two or three groups, corresponding to ceremonial sections. They are held almost daily, with logs of babassu palm or silkcotton tree, painted with annatto dye according to the phase of the ceremonial cycle. On arriving at the patio, the racers are bathed by women, who in generally only take part at the end. Numerous comments are made in a playful tone exalting the performance of the racers throughout the whole day.

In parallel with the log races, the archery games gradually became more intense as a practice accentuating competition in a public and ritualized mode, reaffirming interpersonal alliances. On ceremonial occasions these games consist of competitions held later in the day after the log racing, when everyone sets off to a site in the forest close to the village. Sometimes the game is held in front of the houses, but always in the late afternoon. Pairs are formed in groups (members of different ceremonial sections) that compete in arrow shooting on radiating paths. Boys and women generally stay at the other end to collect the arrows and return them to the participants.

Two modalities of this game exist, following on from each other as the ceremonial cycle unfolds and for which the Parkatêjê use different types of arrow. The first involves shooting downwards, making the arrow hit the front of a small bow stuck in the ground a metre away from the archer so that it then rises and falls about three hundred metres further on. In the other modality, the arrow is shot upwards and its flight extends even further. After falling to the ground, the distance covered by the participants’ arrows each round determines the winner between the partners. Skilled archers, usually mature women and men, are admired within Parkatêjê society and their performance – along with the fastest and most skilled log racers – is a source for acquiring prestige and a motive for long discussions on the patio.

In 1983, the Gavião held an important ritual cycle linked to male initiation: the Pemp, which had been unperformed for about 25 years, precisely the period of time since definitive contact with the kupên. Although this ritual involves the initiation of young warriors, a high degree of enthusiasm and motivation runs through the whole group, especially when moments of role reversal occur, which foreground the performance of women in the log races and archery games.

The young initiates remain in reclusion for some months in a small house walled with babassu thatch and constructed in the rear part of the village circle, behind the house of one of the ceremonial mentors. Here they receive special training based on bravery and honour, guiding principles in the perpetuation of a warrior ethos particular to the contemporary Gê groups. The initiates only leave this house to take part in collective activities such as hunting and gathering or harvesting the swiddens. Always together, the pemp bathe at an exclusive point of the Mãe Maria creek. Elders claim “it is necessary to bathe a lot in order to grow quickly!”

This solemn period of reclusion where sexual relations and the ingestion of certain foods – such as meat and Brazil nuts are prohibited – in effect marks the passage to maturity.

Note on the sources

There are no works exhaustively describing Gavião culture. The ethnologists Roberto DaMatta, Expedito Arnaud and Iara Ferraz concentrated their studies on the relations involved in interethnic contact. The latter ethnologist, as well as producing an M.Phil. dissertation on the leader of the Gavião, acted as advisor to the group in its efforts to assume control of the Brazil nut production and in the understandings reached between them and the large state companies that had cut across their lands with roads and power transmission lines.

Leopoldina de Araújo undertook research on the Timbira language dialect spoken by the Gavião from 1974 onwards, which served as the theme of his M.Phil. dissertation and doctoral thesis. At the request of Krohokrenhum, the Gavião leader, who was concerned to recuperate use of the dialect, he produced a bilingual collection of myths to be employed as didactic material in the village school.

The video by Vincent Carelli, Eu já fui seu irmão (Once I was your brother), depicts a visit made by the Gavião to the Kraô, another Timbira group, and the return visit by the latter. This video was commented upon in an article by the director himself and Dominique Gallois. There are also two videos directed by one of the Gavião, Xontapti Totore Payroroti.

Sources of information

- ALVAREZ, André et al. A construção da aikrepoti : atividade etnopedagófica. Boletim da ABA, Florianópolis : ABA, n. 20, p. 4-5, dez. 1993.

- ARAÚJO, Leopoldina Maria Souza de. Aspectos da língua gavião-jê. Rio de Janeiro : UFRJ, 1989. (Tese de Doutorado)

. La escuela : instrumento de resistencia de los Parkatejê. In: AIZPURO, Pilar G. (Coord.). Educación rural e indígena en Iberoamerica. Mexico : El Colegio de Mexico/CEH ; Madrid : Universidad Nacional de Educación a Distancia, 1996. p. 287-300.

. Estrutura de alguns tipos de frases declarativas-afirmativas do dialeto gavião-jê. Florianópolis : UFSC, 1977. (Dissertação de Mestrado).

. Fonologia e grafia da língua da comunidade parkatejê (timbira). In: SEKI, Lucy (Org.). Lingüística indígena e educação na América Latina. Campinas : Unicamp, 1993. (Coleção Momento).

. Retenções lexicais no dialeto parkatejê. Moara: Rev. dos Cursos de Pós-Graduação em Letra, Belém : UFPA, n. 4, out. 1995/mar. 1996.

- ARNAUD, Expedito. O comportamento dos índios Gaviões de Oeste face à sociedade nacional. In: --------. O índio e a expansão nacional. Belém : Cejup, 1989. p. 365-426. Publicado originalmente no Boletim do MPEG, Antropologia, Belém, v. 1, n. 1, p. 5-66, jun. 1984.

- BELTRÃO, Jane Felipe. Laudo antropológico : Reserva Indígena Mãe Maria, em Bom Jesus do Tocantins, PA, a propósito da BR-222. Marabá : Procuradoria da República, nov. 1998.

- CAPELLI, Jane de Carlos Santana; KOIFMAN, Sérgio. Avaliação do estado nutricional da comunidade indígena Parkatejê, Bom Jesus do Tocantins, Pará, Brasil. Cadernos de Saúde Pública, Rio de Janeiro : Fiocruz, v. 17, n. 2, p. 433-8, mar./abr. 2001.

- FERRAZ, Iara. De "Gaviões" à "Comunidade Parkatejê " : uma reflexão sobre processos de reorganização social. Rio de Janeiro : Museu Nacional, 1998. 222 p. (Tese de Doutorado)

. Os índios Parkatejê 30 anos depois. In: MARTINS, José de Souza (Org.). O massacre dos inocentes : a criança sem infância no Brasil. São Paulo : Hucitec, 1991. p. 21-35. (Ciências Sociais)

. Lições da Escola Parkatêjê. In: SILVA, Aracy Lopes da; FERREIRA, Mariana Kawall Leal (Orgs.). Antropologia, história e educação : a questão indígena e a escola. São Paulo : Global, 2001. p.275-99.

. Os Parkatejê das matas do Tocantins : a epopéia de um líder Timbira. São Paulo : USP, 1983. 151 p. (Dissertação de Mestrado)

. Résistance Gavião : d'une frontiere l'autre. Ethnies, Paris : Survival International, n. 11/12, p. 81-6, 1990.

; LADEIRA, Maria Elisa. Algumas questões sobre o Convênio CVRD/Funai (Projeto Ferro Carajás) : a política integracionista e a aplicação de recursos. In: ENTRE la resignación y la esperanza : los grandes proyectos de desarrollo y las comunidades indígenas. Assunción : Centro de Estúdios Humanitarios, 1989. p. 83-90.

- GALLOIS, Dominique Tilkin; CARELLI, Vincent. Diálogo entre povos indígenas : a experiência de dois encontros mediados pelo vídeo. Rev. de Antropologia, São Paulo : USP, v. 38, n. 1, p. 205-59, 1995.

- KOIFMAN, Sérgio et al. Câncer cluster among young indian adults living near power transmission lines in Bom Jesus do Tocanins, Pará, Brazil. Cadernos de Saúde Pública, Rio de Janeiro : Fiocruz, v. 14, n. 3, p. 161-72, supl., 1998.

- LARAIA, Roque de Barros; MATTA, Roberto da. Índios e castanheiros : a empresa extrativista e os índios no Médio Tocantins. Rio de Janeiro : Paz e Terra, 1978. 208 p. (Estudos Brasileiros, 35)

- SIMONIAN, Lígia Terezinha Lopes. Direitos e controle territorial em áreas indígenas amazônidas : São Marcos (RR), Urueu-Wau-Wau (RO) e Mãe maria (PA). In: KASBURG, Carola; GRAMKOW, Márcia Maria (Orgs.). Demarcando terras indígenas : experiências e desafios de um projeto de parceria. Brasília : Funai/PPTAL/GTZ, 1999. p. 65-82.

- TAVARES, Edelweiss Fonseca. Perfil metabólico e fatores de risco cardiovascular na comunidade indígena Parkatejê. São Paulo : Unifesp/EPM, 2001. (Tese de Doutorado)

. et al. Relação da homocisteinemia com a sensibilidade à insulina e com fatores de risco cardiovascular em um grupo indígena brasileiro. Arquivos Brasileiros de Endocrinologia e Metabologia, São Paulo : s.ed., v. 46, n. 3, p. 260-8, 2002.

- Eu já fui seu irmão. Dir.: Vincent Carelli. Vídeo Cor, NTSC e Betacam SP, 32 min., 1993. Prod.: CTI-SP

- Kry Rytaiti. Dir.: Xontapti Totore Payroroti. Vídeo Cor, VHS, 6 min., 1993.

- Pemp. Dir.: Vincent Carelli. Vídeo Cor, VHS/NTSC, 27 min.

- To kayrere Kry Ritayti Na. Dir.: Xontapti Totore Payroroti. Vídeo Cor, VHS, 13 min., 1993.