Galibi Marworno

- Self-denomination

- Where they are How many

- AP 2822 (Siasi/Sesai, 2020)

- Linguistic family

- Creoulo

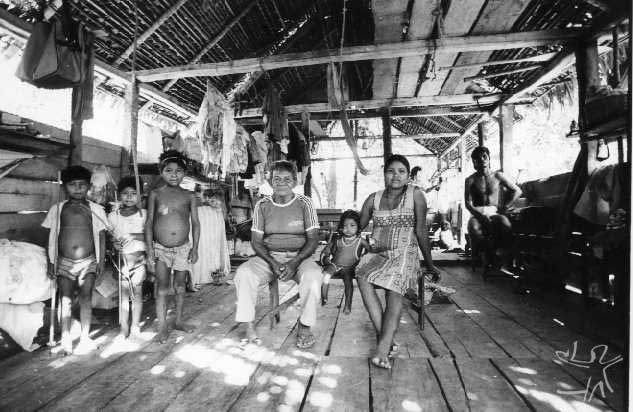

The Galibi-Marworno, inhabitants of the vast savannahs and flooded plains of northern Amapá – a country of white birds and dark alligators – call themselves a “mixed and united” people.

Their food is simple and healthy: fish, manioc cereal and tucupi (a seasoning prepared of pepper and manioc juice). In their festivals, there must be caxiri, the wine of the Indians, of the shamans and the karuãna spirits. The Great Festival is for Holy Mary, the axis-mundi is the Turé pole, the Great Snake their favorite story, but the real hero is Iaicaicani.

Name

Galibi-Marworno is a very recent self-designation, which has become fixed mainly in the last decade. In some contexts, it has come to substitute the term "Galibi of the Uaçá" or, simply, "of the Uaçá", "Uaçauara [= from the Uaçá]" or "mun Uaçá" ("people of the Uaçá", in patois, the creole language widely used in the region). Those who use this name as a self-designation belong to a people who derive from ethnically diverse populations: Aruã, Maraon, Karipuna (speakers of língua geral, derived from Tupi), "Galibi" (speakers of língua geral, derived from Galibi) and even non-Indians.

Galibi, the first term comprising the self-designation, results from the application of this name to the entire population of the Uaçá River by the Border Inspection Commission and the Indian Protection Service. The Galibi-Marworno do not identify themselves, nor recognize kinship with, the Galibi population of the coast of Guiana (who actually call themselves Kaliña) who have a small number of families living in the vicinity of the Uaçá River: a group that migrated from French Guiana in the 1950s and settled on the Brazilian banks of the lower Oiapoque River.

Marworno, the second term of the self-designation, has more to do with the active presence of assistance agencies and reflects a more recent movement over the last three decades. The terms Maruane or Maruanu refer to one of the ancestral ethnic groups of the present population and began to be used by the neighboring Palikur and Karipuna in order to represent their difference from the Galibi-Kaliña families.

In the ethnopolitical movement involving assemblies and which resulted in the creation of the Association of the Indigenous Peoples of the Oiapoque (APIO), this differentiation became more crystallized by the use of the composite term Galibi-Marworno. It is still a self-designation used in specific contexts, in which the goal is to demarcate ethnic boundaries in situations where such categorical identity definitions make sense: in the population lists of FUNAI, in political assemblies, in regional political elections, etc. However, in more localized and daily contexts, where identity boundaries are not so precise, the terms "from the Uaçá" or "Uaçauara" continue to be used.

Language

Actually the Galibi-Marworno population uses as its maternal language a variation of the creole spoken in French Guiana. This dialect is used as a língua franca by the indigenous peoples of the Lower Oiapoque, who recognize phonetic differences between the dialect spoken by the Karipuna and the dialect spoken by the Galibi-Marworno. This “indigenous” creole is distinct from the “Black” creole of French Guiana both in terms of its phonetic and lexical aspects which still have not been sufficiently studied. The creole dialect came to predominate among the Galibi-Marworno to the detriment of the various languages spoken by their ancestors. Nimuendaju, who was on the Uaçá River in 1925, recorded more than 100 words in the Galibi language, a dozen in the Aruã language and only two words in Maraon.

French creole has remained the maternal language despite the efforts of the SPI to prevent its use, since it implied Galibi-Marworno use of French habits, which was not looked upon favorably by the Brazilian state in a boundary area which was only definitively annexed to Brazilian territory in 1900. The school built in the Uaçá region in 1934 prohibited the use of creole by the students, reinforcing this prohibition with the use of the palm-slapper (an instrument of punishment).

The study of this variant of French creole began in the 1980s, among the Karipuna and Galibi-Marworno, by Francisca Picanço Montejo, linguist of the Indigenist Missionary Council, who had technical assistance from the linguists Ruth Montserrat (UFRJ) and Márcio Silva (then at UNICAMP). An orthography of Karipuna and Galibi-Marworno was produced and its grammar systematized. According to this orthography, the dialect is designated by the word "kheuol". The language is being studied by other researchers among the Karipuna.

Location

The greater part of the Galibi-Marworno population lives in the Uaça Indigenous Area (AI), which has been homologated and officially registered, consisting of 470,164 hectares, in the municipality of Oiapoque, in the northern part of the state of Amapá. The Uaçá River, the major reference point for these people, flows into the same estuary as the Oiapoque River, which demarcates the border between Brazil and French Guiana. Several Galibi-Marworno families reside in the Juminã Indigenous Area, which has 41,601 hectares, near the Juminã stream, which flows into the Oiapoque River. The Juminã Indigenous Area is located between the Uaçá and Galibi indigenous areas, and also has as its northern boundaries the Uaçá and Oiapoque rivers.

Population

According to the Oiapoque Regional Delegacy of FUNAI (National Indian Foundation), censuses from April 1998 show that the large village of Kumarumã, located on the mid-Uaçá River, had a population of 1,506 people. The village of Tukai, near the headwaters of the Uaçá River, and near the FUNAI Vigilance Post built on kilometer 92 of state highway BR-156 has 34 inhabitants. In the village of Laranjal (also called Uahá), located near the Juminã stream, there are 88 people. Besides these three villages, one can also add the 89 dwellers of Flecha village, located on the Urukauá River, who came from the Uaçá. By living near this river, which is a place of Palikur villages, these families are considered to be "Palikur" in the FUNAI censuses, although they have the same ancestry as the Galibi-Marworno.

Contact history

The history of the Galibi-Marwono population may be summarized as the trajectories of distinct populations, migrants from ancient missions, fugitives from captivity, who created local networks of sociability coincidentally with, or based on previous experiences in broader networks of interethnic contact.

At the beginning of colonization, the region could be described as “open” to all the vicissitudes of history. For example, the Maraon are mentioned in reports from the XVIth Century as inhabitants of the Uaçá region. The Aruã migrated to the region from the Guianas, in the XVIIth Century, fleeing from Portuguese incursions in the region of the lower Amazon, but they were enslaved by the French. In the first half of the XVIIIth Century, the Maraon and the Aruã were settled in Jesuit missions on the coast of French Guiana, together with the Galibi. With the expulsion of the Jesuits from Guiana between 1765-68, a Portuguese offensive invaded the ancient territories of missions, villages, and colonial settlements, emprisoning the indigenous population and deporting the Indians to the Amazon. The deported Aruã returned the next century and settled on the upper Uaçá. Many of the present-day Galibi-Marworno remember slave-hunters and their stories speak of merchants passing through their territory.

After Marechal Rondon’s visit to the area in the 1920s, the Brazilian state decided to consolidate its boundary with French Guiana and put the indigenous populations of the Uaçá under its control. It is from that time on that, in the words of one Galibi-Marworno, the “union” of the people of the Uaçá began under the same administration, a very present and active state and military apparatus, especially in the place called Encruzo, founded especially to implement control over the Indians of the region. On the other hand, even though it was for strategic reasons, the SPI “brought together” the Indians under their control, reinforcing indigenous identity of the peoples of the region, through its presence and activities. The SPI, which maintained an active presence in the region from 1945 to 1967, removed intruders and “foreign elements” from the area, such as merchants, creoles, French and English who had settled on the banks of the rivers in order to exploit their natural resources , such as gold and good quality timber, which are abundant in the region. According to one informant, these foreign elements entered with the connivance of certain chiefs. The Indians worked for them but got nothing in return.

During this time the SPI introduced specific norms among the Indians, such as the prohibition of alcohol and regulamentation of marriages between Indians and non-Indians. New concepts related to work and commerce, controlled by the Indian agency, were introduced. Among the Galibi-Marwono and the Karipuna, the school — an institution of major importance and impact — was responsible for grouping the population into larger villages, for the use of the Portuguese language and to instil respect for national emblems, such as the National Hymn and the raising of the banner. The school served as a justification for the agglutination of almost all Galibi-Marworno families in the village of Kumarumã. During this time, also, a military ranch was established on the Suraimon, upper Uaçá, for the purpose of raising buffaloes for the military at Clevelândia do Norte.

Between the end of the 1960s until the end of the 80s, both FUNAI and CIMI worked in the region of the Uaçá, and to a certain extent they succeeded in reverting the previous situation. The demarcation of lands, the organization of regional political assemblies and the project for differentiated education were given priority, thus promoting consciousness of a new self-esteem among the Indians of the Uaçá. Notable features included the emphasis given to culture and indigenous rights, as well as the incentive to using the kheoul language, stimulating the Indians to openly consider it as their maternal language. For five years, from 1990 to 1995, CIMI promoted a pedagogical course for the formation of indigenous teachers. FUNAI dismantled the buffalo ranch set up by the military on the Uaçá, and the installations at Encruzo were also partially dismantled; only the Indian post and the place for punishment and temporary exile for law-breakers, who were submitted to hard labor, were kept. It is worth noting that this custom of punishment is ancient in the region and precedes the SPI. The Galibi-Marworno recall powerful and feared chiefs who executed such punishments. The SPI, however, conferred on this institution the legitimacy of the state. This penal function of Encruzo was abolished by the Assembly of Indigenous Peoples of the Uaçá in January, 1996.

Subsistence and commercial activities

The subsistence activities of the Galibi-Marwono vary according to the annual seasons: dry and rainy, the first between July and November and the second between December and June. According to the time of the year, or depending on the most immediate needs, the activities take place on the upper part of the river (in the forests which are the sources of game and timber, or in the rivers of the region which are abundant in fish) or on the middle and lower courses (“open” spaces of the savannahs, used principally for planting, on the raised grounds in the midst of flooded lands), as well as for fishing.

The collective labor in the gardens is organized by the system of “invitation”, the maiuhi, or traditional work parties organized among neighbors for the benefit of one, but each family sells its produce individually in the commercial houses of Oiapoque or sometimes Saint Georges (on the French side of the Oiapoque River) where the price is better but where the sale, by law, should be made directly to the consumer, without intermediaries, which is complicated for the Indians. This being so, they sell their produce, either in the market or on request.

In observance of the norms of environmental preservation, in the 80s, it was decided in Assembly that fish and game meat could not be sold outside the Indigenous Area. Fishing is always subject to periods of restrictions in order to protect spawning, especially of the pirarucu, and the hunting of alligators is prohibited. Their weapons for fishing continue to be the traditional bow and arrow, harpoon, hooks, and short spears that the men make with old pieces of iron beaten and worked in the fire. While there are restrictions on hunting and fishing, there is no plan for the preservation of avifauna. The Indians eat all species of birds and are already aware of the scarcity of several types, supposedly due to the high consumption of this kind of food.

There are several small commercial establishments in Kumarumã, some also functioning as bakeries. The custom today is to drink coffee in the morning with tapioca or bread. Other industrialized foods are also consumed more than in the past, but in general the daily menu consists of fish, manioc cereal and tucupi.

Since the 1930s, the Galibi-Marworno produce surpluses which they commercialize, principally manioc cereal. Often, manioc cereal serves as trade “money” to acquire other food products in the village. By an internal agreement among the Indigenous Peoples of the Oiapoque, they do not sell timber, but they have every right to cut boards for the construction of their houses, canoes, bridges and also public buildings such as the school, infirmary, and festival house. They are excellent canoe makers, and these they sell, generally on request, in Saint Georges but also in Oiapoque and on the Cassiporé.

The manufacture of canoes, as well as the felling of trees, is done collectively through the system of “invitation”, in the free periods between agricultural tasks. Lumber is taken from the region of the headwaters of the Uaçá although it is becoming ever more difficult to get access to suitable lumber and even transportation. For the time being, the Indians have no project or plan for the sustainable use of lumber. They also sell artwork but in insignificant quantities: collars made of seeds, beads, monkey teeth and deer bone; engraved gourds, bows and arrows, altogether comprising an ornamental kit. The tips of these arrows are finely worked, the Indians say that they are of the Banahé, an ancient indigenous people of the region. They sell this artwork especially in Saint Georges to the gendarmes and foreign legion, who are major buyers of these objects.

The transportation of merchandise is done with the boats of the community or those which are the property of several Indians. There is a charge collected on each person and cargo. Generally the boat of the community makes the trip every 15 days going by way of the ocean, going round Mosquito Point and entering the Oiapoque. It’s a long trip not counting the wait due to the tidal waves at the estuary of the Uaçá River.

The village of Kumarumã

The village is located on a large island on the left side of the mid-Uaçá River. The houses are arranged in the form of a half-moon, bordering on a submerged field. The village has grown a great deal in the last few years and is not limited only to the cluster of houses bordering the field, but rather extends into the interior of the island. Presently there are 163 houses occupied by, on the average, six to ten people. The houses are very close to one another and the space available for new constructions is already scarce. A great deal of the forest has already been destroyed and the soil is showing signs of erosion at various points. The spatial distribution of the houses on the island is organized in four “points”. The oldest is the point of the Mango or the Captain. In the middle of the island is located Vila Nova street. Then, Bacaba Point street. The street of the port or post, also called Point of the Group in the past, because of the school, does not include indigenous dwellings. The FUNAI post, the school, the infirmary, teachers’ lodgings, and the CIMI headquarters are located there. A bit closer to the center, there are the church and bell of the community and the Festival House or Great House, imposing in its dimensions, which was totally rebuilt by the community in 1996 and inaugurated on the 5th of August for the festival of Holy Mary. Actually this part of the village is divided into three blocks which represent, in reality, the external institutions and/or agents which maintain a presence in the village.

The FUNAI buildings are poorly conserved. The schools, new buildings and repairs on old buildings have been financed through an agreement between the government of Amapá and the APIO (Indigenous Peoples’ Organization of Amapá). CIMI has only one simple, little house. The community area, with the Church and the House of Festivals, is in the center of town. This area is maintained by the entire community through collective work parties and “work teams" under the guidance of a leader. These leaders, heads of extended families who occupy an area of the village are also responsible for collecting the contributions of each family to pay for fuel, necessary for lighting in the village and, sometimes, other services.

One can speak of an effort to “urbanize” the town of Kumarumã, because of the tracing of the streets and electric lightposts. A large watertower was built and a network of pipes was installed to supply water to the houses, but as yet these are not functioning. There is a tendency for rapid growth, especially in Bacaba Point where the area built extends far beyond the landing field. On the other hand, the whole area of forest between Vila Nova and Mango Point is already totally destroyed and occupied by new dwellings. The availability of potable water, the lack of sewage and disposal of household and pharmaceutical waste are problems that demand urgent solutions. From the social point of view, there is another concern, the impossibility of a newly-married couple to build their house next to their mother/mother-in-law, due to lack of space, thus destructuring the matrilocal residence rule, one of the few traditional institutions still functioning.

To get to the village from the riverbed, canoes use a canal, le canal bax which goes to the FUNAI post. Today two large wooden bridges pass over the fields which are flooded in the winter and muddy in the summer. In the winter, canoes are able to get to the banks of the island where the houses for preparing and storing farinha, or cabé, and the individual docks where the Indians make their canoes are located. In the summer, several families still use improvised bridges made of miriti trunks.

The majority of the houses are built on stilts, rectangular in shape with wooden walls and floorboards. A little stairs provides access to the entrance. Generally, there is one or several internal divisions, separating the main room from the sleeping quarters. The Galibi-Marworno normally sleep on mats made of rush covered by a large mosquito-net, where the married couple and their small children sleep. Today, however, many use hammocks and even beds. Mosquito-nets that are set up during the day indicate the presence of sick people or of a woman who has given birth. The kitchen is a partially open area, behind the house, where there is an earthen oven, sometimes a gas stove. There are tables, but generally they are used to pile things up, while the “table” for meals is put on the ground, when the family comes together to eat grilled or boiled fish with farinha, salt and tucupi. There is never much furniture in the Galibi-Marworno houses, but today, several families have televisions and a parabolic antena, besides a prosdócimo, as the Indians say, or freezer, that allows them to preserve food and to chill water and drinks.

The farinha houses, called “cabê”, are always located near the water-line, serve various nuclear families, and are located especially where the women spend many hours of the day, dehusking, scraping and toasting manioc cereal. In the cabê one can find traditional artifacts such as fine and thick sifters, troughs, carrying-baskets, the beiju-turners, the straw-fans, besides the large ovens.

Many families still live according to the traditional ways: the men, after marriage, live in the house of the parents of their wives for two to three years, sufficient time for the marriage to consolidate, generally with the birth of one or two children. Time, also, for the young married husband to get the material necessary for the construction of a new house. Nowadays, sometimes the youths prefer to build a brick house which totally transforms the traditional style of the village.

The relation between father-in-law and son-in-law is peaceful and one of mutual help. In myths, however, the tensions between affines are explicit, demonstrating a movement to expel affinity from daily life to the mythical plane. Nevertheless the status of father-in-law is weighty. In a society in which an indigenous language is not spoken, a youth extends to his father-in-law’s brothers the term by which he calls his father-in-law: beau-père.

Political relations

Traditional chieftaincy was comprised of the chiefs of the local groups, extended families that occupied the islands of the upper Uaçá. Several of these families had more prestige, however, with more numerous families. These succeeded in bringing together local groups for the festivals of Turé or of Holy Mary, when much caxiri was consumed. In this way a network of sociability was formed on the upper Uaçá. There are chiefs who are remembered today as being authoritarian and feared, who at times promoted alliances which were not always beneficial to the families. At the time of Marechal Rondon’s visit, there were respected chiefs whose descendants are still alive in the Uaçá region today.

In Kumarumã, at the present time, there is a strong community sentiment that pervades the institutions. Decisions are always made collectively. The chief is watched over by the vice-chief and the counsellors of the community, as is the chief of the Post who is an Indian.

When disputes or more serious cases occur, the offender could be punished by a “cleaning”, a mode of punishment introduced by the SPI, to replace the cruel punishment by the "trunk" (in which the Indians were tied to a treetrunk for several days and flogged), and which the Indians of the Uaçá copied from the Blacks of French Güiana. Until 1996, this cleaning was severe, meaning 30 or more days of work, clearing bamboo-thickets on the banks of the Uaçá river, in Encruzo. This type of punishment was abolished during the Assembly of 1996. Today, ‘cleaning’ is done in the village, in the cases of minor offenses. In the case of more serious aggressions, like knife-cuts or even murders, the guilty are expelled from the village, often for good, or handed over to the authorities. Internal legal measures applied to offenders is an area for research which still needs to be done in the region.

To discuss and settle internal questions, the chief, vice-chief and counsellors get together with the community after calling everyone together. Every year an internal assembly is held to discuss political strategies, economic projects and internal questions. The general assemblies which are held every two years, however, cover all topics. For these general assemblies, the Indians invite representatives of the government, the military, the authorities, and people connected to the NGOs, besides Indians from other regions. In 1991 the APIO was founded which represents all of the ethnic groups of the region and which has its own center and administrative structure in Oiapoque, which allows for greater autonomy, bureaucratic agility and the sending and administration of projects and money. From 1994 on, party politics and state policy have been more present in the lives of the Indians who have come to depend more and more on the state of Amapá.

The agreements signed between the APIO and the state government or the municipality of Oiapoque have facilitated various development projects in indigenous areas such as the building of schools and lodging for teachers, repairs on the infirmaries, promoting courses for midwives, besides paying teachers, assistants, lunch-makers, and health agents.

The present mayor of Oiapoque is a Galibi-Marworno Indian who was elected with the backing of the PSB (Partido Socialista Brasileiro, Brazilian Socialist Party), the party of the ex-governor of the state of Amapá, J. A. Capiberibe (re-elected in 1998). The state deputy Janete Capiberibe is also very active, making frequent trips to the area, and supporting the indigenous communities on various occasions. In the elections of 1998, the Indians of the Uaçá, Juminã and Galibi of the Oiapoque reserves voted en masse for Governor Capiberibe. Precisely for that reason, the Indians fear that a change in the government could hurt them, which in fact makes them more dependent on “politics”, even if it’s due to a lack of options.

With all of this political change, the traditional ways of administration have become more complicated and the chiefs say that they are tired and sometimes worn out. But one thing is certain: in moments of crisis, the Indians act together and are firm in their resistance.

Mythology

The myths recorded among the Galibi-Marworno relate and interpret notable historical facts, always localized in the specific environment of the Uaçá which, in turn, is also in some way submitted to interpretation, such as the rivers and lakes, the mountains, and strange geological formations. One example is the myth of the war between the Galibi and the Palikur, a veritable founding metaphor for the interethnic relations in the region, the setting for which extends from the upper Urucauá to the Maroni River in French Guiana. Several versions of this myth have been recorded among the Palikur of Kumenê, Galibi-Marworno and Palikur of Kumarumã. The last is undoubtedly the richest and most complex. In this version, the confrontation between the two nations, which lasted for decades, ends on the one hand, a relation of affinity between enemies, that is, Palikur maternal uncle/Galibi sister’s son, warrior chiefs of their respective nations and, on the other, the relationship of kinship between beings of this world and of the invisible world, that is, a Galibi, the first of his “nation”, is born from the union of a Palikur woman, of this world, and a karuãna, invisible being, father.

Another example is the myth of the shaman Uruçu, who really existed and lived on Bambu island. They say that this shaman, having been persecuted and captured by slavehunters from Caienne, succeeded in escaping at high sea, by transforming himself into a snake or jaguar at the bottom of the sea, thanks to the help of his karuãna and pakará and maráca which he had taken with him. On returning to the Uaçá, he fled to the upper Tapamuru (tributary of the Uaçá), where he requested that his spirit helpers, the karuãna, interrupt the flow of this river with enormous displacements of earth, in order to remain protected from any further attacks. This river actually has this feature: obstructed in its mid-course, it flows underground in its riverbed.

Another myth of great importance in Galibi-Marwono cosmology is the myth of the Great Snake. The Galibi-Marwono narrate the myth making reference to the Palikur Indians. The interesting feature is that this version, from a people whose social organization shows a matrifocal tendency, inverts that of the Palikur, who have patrilineal descent. The myth makes reference to Tipoca mountain, a very salient elevation in the level countryside of the middle Uaçá River. There one can find seashells and seasnails, probably the remains of a time when there was communication between that mountain and the sea, a fact which is still being investigated geologically.

The narrative recounts that on Tipoca mountain, there used to live in the past many Palikur, in large villages, especially on Caraimura point. The Great Snake lived there with his wife and son on Tipoca point. His "breath" was located at the place called Mamã dji lo and it was through this hole that he threw the rests of his food and also would go out into this world. The Indians liked to bathe in the lake and the Great Snake, who only ate meat, would come out of his hole, go to Caraimura point and kill many Palikur that he saw as monkeys. Human flesh for him was game, he only ate monkeys and thus each day he would kill several Indians. His wife did not like to eat meat; she only ate the seafood that her husband would bring for her. (In the Palikur version, it’s the female snake who is the devourer of people, and the male snake is a vegetarian and healer).

One day, a little Indian boy named Iaicaicani went to the island of Mamã dji lo, with bow and arrows to kill parrots and tucanos, which are very numerous in that place. Suddenly, he fell into a hole. As if in a dream, he found himself in another world. There he came upon a woman who asked him: “what are you doing here?" "I’m lost", he answered. Then the woman said: “I will give you a bath, I am afraid that my husband will kill you". After giving him a bath, she hid him underneath a pot. When the male snake arrived, his wife filled his belly with monkey and cachiri. He had also brought crabs and lobster for his wife. He smelt something different, tasty. Several times his wife denied that there was something different in the house, but she ended up confessing that there was a little Indian boy, and pled with him not to kill him. Fortunately, the snake had already eaten and his belly was full. "Well", Tipoca [ the Great Snake]said, “you will be like my son and will play with little Tipoca".

Iaicaicani succeeded in escaping and returned to his village to tell what was happening. Then, the Palikur asked his help in preparing a trap to kill the snake. Iaicaicani revealed that the snakes rested on top of the rocks at a certain time of the day, and the Indians planned a trap to kill them at that time. Iacaicani asked his kin to kill only the male and not the female. The Indians, however, killed both. Iacaicani and little Tipoca, who had gone for a walk, came back because little Tipoca heard thunder, the voice of his father. He went crazy when he saw what had happened with his parents and went away to live in Marapuwera lake, where another snake of the same name, his paternal uncle, lived. Iacaicani visited his kin and said: "I could have returned to live with you, but you killed the female snake, a sign that you don’t want me to come back". He left and everyone wept a lot. "I am going to Marapuwera, to live with little Tipoca". The story says that he also transformed into a snake and his karuanã can be called by the pajés in curing sessions and at the time of the Turé ritual. Even so, he is considered to be a little hero.

It is evident in this, and in other, myths, that the Galibi-Marwono are aware of the changing conditions of inhabited space. In fact the region is one of the confluence of the Uaçá River basin with the open sea, a region which geologically is in constant redefinition. Such geological changes are themes for mythic narratives, which deal with beings that occupy the same terrain, which is very much specified and marked in mythic events.

Pajé and Turé

From what has been said, one perceives that the contact with the Karuãna, the auxiliary spirits of the pajés and dwellers of the “other world”, are an important aspect of Galibi-Marwono cosmology and characteristic of their shamanism. The Karuãna are not all alike and perform different functions, some are more powerful than others and at the same time that they help, they are also dangerous and need to be controlled. The karuãna kamará, the most resistant warriors, never decend onto the ritual dance ground where the Turé festival is celebrated and do not sit on the benches, but remain watchful, on the top of the ritual pole, for whatever attack or undue intromission of spirits of other shamans, enemies or jealous, ready to send their sorcery.

Recent research has shown the importance of the avifauna for the cosmology of this population. The birds are intimately related to the shamans, as individuals. Each shaman has a small bird-shaped bench, on which he sits in order to realize any sort of activity that involves contact with the karuãna. The pajé Iok, for example, has a bench in the form of the red macaw, which belonged to his mother, a recognized shaman in Kumarumã. Before dying she is supposed to have said to her son: "take and keep this bench. When the Indians dance Turé, bring it with you and at that time my karuãna will come to visit you".

The bird-benches are covered by designs, which show a variation on two basic motifs: the kroari and the dãndelo, which are not simply ornamental techniques, but serve to express a vast array of meanings and representations. The two motifs, one diamond-shaped and the other a zigzag, also express a founding metaphor for the groups of the Uaçá, which is grounded in the dichotomy of openness to the outside or closure.

The Turé is considered to be a traditional ritual of the Galibi-Marwono. It was usually celebrated in October/November, time of the dry season and the felling of the gardens. But it is no longer held today. For the Indians, the Turé is something very serious and dangerous and must be celebrated according to well-defined rules in order for it to be an occasion of happiness and not one of tragedy. The Galibi-Marworno do not have a practicing shaman in the village. The shaman Uratê is a Palikur; in the past it was his wife, a Galibi and also a shaman, who directed the ritual. The pajé Aniká, resident in Encruzo, a man who was strong in his dealings with the Karuãna, does not practice anymore due to his conversion to the evangelical religion. Another pajé today lives in Oiapoque and does not visit the village anymore.

The Indians tell the story of two Galibi who took it on themselves to hold a Turé, using the bench of a deceased shaman, but since they had not been initiated, especially to having an adequate relationship with the spirits of supernatural entities, these spirits arrived, confused and dissatisfied onto the sacred space, not receiving the offerings expected, which caused the death of one of the organizers of the Turé several days later. This was the explanation given for not holding the ritual.

The Galibi-Marworno are perplexed by the boldness and frequency with which the Karipuna hold Turés. From all of this one can conclude that this ritual still has a very strong traditional significance present among the population of Kumarumã. The Galibi even declare that the great hat, or plumage, a headdress used in the Turé, is originally theirs and not the Palikurs’ as is supposed.

On the other hand, while they do not openly display the Turé, the adult men get together during the nights of the full moon, in the month of October, in an isolated house in the fields, the home of the pajé Uratê, and sing until dawn, drinking caxiri, in order to be happy with the Karuãna and to thank them for the cures they have granted. On these occasions, the spirits of the dead also descend, such as the wife of Uratê, a pajé herself and who comes to sit on his bench, a very beautiful sculpture of a red macaw, carefully kept by his family for years.

Thus, even without shamans, shamanism is still alive. On the other hand, many adult men practice the potá, or blowing, as a form of cure. While the shamans exercised their activities under the influence of the spirits of the forest and waters, and of other shamans living or dead, the practice of potá is not done through these spirits and does not imply any powers over natural phenomena. The potá cures various types of sicknesses, several of them caused by the nightbird kaiuiurú, which flies backwards with its belly turned up. For this, they use herb baths, blowing, smoke curing and orations in the old language or patois.

Rituals of popular Catholicism

The Catholic religion, which the Galibi-Marworno say they follow, is observed through the rituals connected to the life cycle: baptism, marriage and funerals. The first two are celebrated by the priest when he visits the village. Funeral rites are more traditional. The deceased lies in wake in the house, the whole night, accompanied by songs in patois and much liveliness, as people eat, drink, play and happily converse. Some time after the burial, the same ritual is repeated, for one whole night until dawn.

The calendar of festivals includes the festival of Holy Mary which begins on the 5th of August and ends on the 17th. It is preceded by the charité,[charity, alms] when a procession with musicians and the maître charité visit all the houses of the village to collect a contribution in money or in kind for the festival. Afterwards, the main pole is raised, laden with fruits, in front of the church. Litanies are held at night and processions with the Virgin, in the afternoon. A large number of festeiros [those who sponsor and organize the festival](there were 16 in 1996), make a promise, on the year before the festival is held, to dedicate themselves to the realization of the fest. They and their families prepare the food, buy the drinks, decorate the hall and take care of public orderliness, a necessary task because of excessive drinking. Many people come from other villages, from the Curipi, Urucauá, Oiapoque, Cassiporé, Saint Georges and even Caienne. Employees of FUNAI and other authorities also participate. If it is election time, the candidates take advantage of the occasion to campaign, helping with the expenses which is called a present “of politics". The food is abundant, there is no fish, however, only meat. The dance lasts three days, it being mandatory to remain in the hall the whole night until dawn. Other festivals include São Benedito, at Christmas time, and the Brazilian civil festivals.

Notes on sources

The first sources on the inhabitants of the Uaçá go back to the XVIIth Century. According to the information compiled by the Baron of the Rio Branco, in his diplomatic work "Border Disputes" (Paranhos 1945, VI: 101), the Englishmen Keymis, Tatoon and Harcourt passed through the region of the Watz (Uaçá) and Arcooa/Arracow (Urukauá) rivers and published reports in 1608 and 1613, in which they mention the presence of Charibe, Morrowinne, Wiapocoorie and Yao Indians in that region.

On the XVIIIth Century, some information on the inhabitants of the Uaçá River basin can be found in the studies by Hurault (1972) and Coudreau (1893). The information in these documents deal principally with the migrations of various ethnic groups, notably the Aruã migration, and the activities of the Jesuits and their intentions to establish missions in the region of the Uaçá. In this regard, the letters of Fathers Fauque and Lombard are primary sources, organized in the "Lettres edifiantes et curieuses (1700-83)". Studies on the documents of this time may be found in the articles by Lombard (1928) and Froidevaux (1901).

In the XIXth Century, the scientific travellers Léprieur and Coudreau passed through the region and their works are two of the rare sources on the inhabitants of the Uaçá basin in this period.

In the 20th Century, sources on the Indians of the Uaçá multiply, among which we find government reports, anthropological and linguistic researches. Included among the reports of government commissions and agencies, there are those of the Border Inspection Commission of the War Ministry, which passed through the region in 1927 led by General Rondon and the report by Luís Thomaz Reis, who also passed through the region as Border Inspector in 1936. J.Malcher utilizes data compiled during the time in which the SPI was present among the Indians, data obtained by him and by the Inspector of the Indians Eurico Fernandes, and organized an entry on the Galibi published in the volume "Índios do Brasil: das cabeceiras do Rio Xingu, dos Rios Araguaya e Oiapoque" [Indians of Brazil: from the headwaters of the Xingu River, the Araguaya and Oiapoque], edited by Rondon. From the 1970s on, Frederico de Oliveira began working among the Galibi of the Uaçá as head of the FUNAI post, accumulating a rich documentary archive on the Indians of the region and the activities of the indigenist agency. This archive was recently organized and restored and is now being used as a source of studies by researchers of the region.

In terms of works of an anthropological nature, Curt Nimuendajú wrote on the "Indians of the Uaçá" in his work on "the Palikur and their neighbors". The anthropological texts that were produced afterwards on the Galibi-Marworno, focused primarily on the activities of governmental agencies. This is the case of the article by Expedito Arnaud (1969) titled "os índios da região do Uaçá e a proteção oficial brasileira" [The Indians of the region of the Uaçá and official Brazilian protection] and the Master’s thesis by Assis (1980) on school education among the Indians of the Uaçá. Arnaud and Assis also wrote articles on shamanism and environmental questions, respectively, in which they deal with the Galibi-Marworno population together with the other indigenous peoples of the Oiapoque.

From the 1990s on, the author of this entry began research among the indigenous peoples of the region. Under her guidance, Edson Martins Jr. gathered data among the Galibi-Marworno, producing scientific reports and a residence map of the village of Kumarumã. Antonella Tassinari has written a doctoral thesis on the Karipuna, in which she presents historical and ethnographic data on the Galibi-Marworno. The biologists Luís Fábio Silveira and Renato Gaban, together with Lux Vidal, wrote an interdisciplinary report on the avifauna in the region of the Uaçá. The author of this entry has produced various articles on cosmology, art, myth and history, in the form of unpublished scientific reports. Field research among the Indigenous Peoples of the Oiapoque, undertaken by Lux Vidal and her advisees, was supported by the FAPESP (Foundation for Research Support of the State of São Paulo) through the Thematic Projects titled: "Anthropology, History and Education" - Mari/USP (Process no. 94/3492-9) and "Indigenous Societies and their Boundaries in the Southeastern Region of the Guianas" - NHII/USP (Process no. 95/0602-0).

Members of CIMI have published several works of a linguistic nature, on the kheuol dialect, focusing on bilingual education. This is the case of the article by Spires (1989) which deals with the experiences of bilingual education among the Karipuna and Galibi and the Kheuol-Portuguese/Portuguese-Kheuol dictionary, organized by Picanço.

Sources of information

- ALMEIDA, Ronaldo Rômulo Machado de. Traduções do fundamentalismo evangélico. São Paulo : USP, 2002. 161 p. (Tese de Doutorado)

- ARNAUD, Expedito C. Os índios da região do Uaçá (Oiapoque) e a proteção oficial brasileira. In: --------. O índio e a expansão nacional. Belém : Cejup, 1989. p. 87-128. Publicado originalmente no Boletim do MPEG, Antropologia, Belém, n.s., n. 40, jul. 1969.

. O sobrenatural e a influência cristã entre os índios do rio Uaçá (Oiapoque, Amapá) : Palikur, Galibi e Karipúna. In: LANGDON, E. Jean Matteson (Org.). Xamanismo no Brasil : novas perspectivas. Florianópolis : Fapeu, 1995. p. 297-331.

. O xamanismo entre os índios da região do Uaçá (Oiapoque, Amapá). Boletim do MPEG: Antropologia, Belém : MPEG, n. 44, n.s., 26 p., jun. 1970.

ASSIS, Eneida Corrêa. Escola indígena, uma "frente ideológica"? Brasília : UnB, 1981. (Dissertação de Mestrado)

. As questões ambientais na fronteira Oiapoque/Guiana Francesa : os Galibi, Karipuna e Paliku. In: SANTOS, Antônio Carlos Magalhães Lourenço (Org.). Sociedades indígenas e transformações ambientais. Belém : UFPA-Numa, 1993. p. 47-60. (Universidade e Meio Ambiente, 6)

- CASTRO, Esther de; VIDAL, Lux Boelitz. O Museu dos Povos Indígenas do Oiapoque : um lugar de produção, conservação e divulgação da cultura. In: SILVA, Aracy Lopes da; FERREIRA, Mariana Kawall Leal (Orgs.). Práticas. pedagógicas na escola indígena. São Paulo : Global, 2001. p. 269-86. (Antropologia e Educação)

- CEDI. Galibi do Uaçá. In: RICARDO, Carlos Alberto; GALLOIS, Dominique T., coords. Povos Indígenas no Brasil. v. 3, Amapá/Norte do Pará. São Paulo : Cedi, 1983. p. 40-61.

- COUDREAU, Henri. Chez nos indiens. Paris : Librairie Hachette, 1893.

. La France Equinoxiale. Paris : Challamel Ainé Ed./ Librarie Coloniale, 1887.

- DIAS, Laercio Fidelis. Curso de formação, treinamento e oficina para monitores e professores indígenas da reserva do Uaçá. In: SILVA, Aracy Lopes da; FERREIRA, Mariana Kawall Leal (Orgs.). Práticas. pedagógicas na escola indígena. São Paulo : Global, 2001. p. 360-78. (Antropologia e Educação)

- FRIKEL, Protasio. Os Kaxúyana, notas etno-históricas. Belém : MPEG, 1977. (Publicações Avulsas, 14)

- FROIDEVAUX, Henri. Les lettres edifiantes et la description de la mission de Kourou. Journal de Société des Americanistes, Paris : Société des Americanistes, n. 3, 1901.

- HURAULT, Jian-Marcel. Français et indiens en Guyane, 1604-1972. Paris : Union Générale d’Editions, 1972.

- LEPRIEUR, M. Voyage dans la Guyane Central. Bulletin de la Société de Géographie, Paris : Société de Géographie, v. I, 2a. Sér., p. 201-29, 1834.

- LOMBARD, J. Recherches sur les tribus indiennes qui occupaient le territoire de la Guyane Française vers 1730 après des documents de l’époque. Journal de la Société des Americanistes, Paris : Société des Americanistes, n. 20, n.s., p. 121-55, 1928.

- MALCHER DA GAMA, José. Os Galibi. In: RONDON, Cândido Mariano da Silva. Índios do Brasil : das cabeceiras do rio Xingu, dos rios Araguaia e Oiapoque. v. 2. Rio de Janeiro : CNPI, 1953.

- MUSOLINO, Álvaro Augusto Neves. A estrela do Norte : Reserva Indígena do Uaçá. Campinas : Unicamp, 1999. 242 p. (Dissertação de Mestrado)

- PARANHOS, José Maria Silva. Obras do Barão do Rio Branco : questões de limites. v. III: Guiana Francesa, 1a. Memória e v. IV: Guiana Francesa, 2a. Memória. Rio de Janeiro : Ministério das Relações Exteriores, 1945.

- PICANÇO MONTEJO, Francisca (Org.). O nosso dicionário português-Kreoul/No djisone Kheuol-Portxige, povos Karipuna e Galibi-Marworno. Belém : Mensageiro, 1988. 188 p.

- RIVET, P.; REINBURG, P. Les indiens Marawan. Journal de Société des Americanistes, Paris : Société des Americanistes, v. 13, n.s., p. 103-18, 1921.

- SPIRES, Rebecca. Karipuna e Galibi. In: EMIRI, Loreta; MONSERRAT, Ruth (Orgs.). A conquista da escrita : encontros de educação indígena. São Paulo : Iluminuras/ Opan, 1989. p. 65-75.

- TASSINARI, Antonella Maria Imperatriz. Contribuição à história e à etnografia do Baixo Oiapoque : a composição das famílias e a estruturação das redes de trocas. São Paulo : USP, 1998. (Tese de Doutorado)

. Da civilização à tradição : os projetos de escola entre os índios do Uaçá. In: SILVA, Aracy Lopes da; FERREIRA, Mariana Kawall Leal (Orgs.). Antropologia, história e educação : a questão indígena e a escola. São Paulo : Global, 2001. p.157-95.

. Os povos indígenas do Oiapoque : produção de diferenças em contexto inter-étnico e de políticas públicas. Florianópolis : UFSC, 1999. (Antropologia em Primeira-Mão, 39)

- VIDAL, Lux B. Mito, história e cosmologia : as diferentes versões da guerra dos Palikur contra os Galibi, entre os povos Indígenas da Bacia do Uaçá, Oiapoque, Amapá. Rev. de Antropologia, São Paulo : USP, v. 44, n. 1, p. 117-48, 2001.

. O modelo e a marca, ou o estilo "misturador" : cosmologia, historia e estética entre os povos indígenas do Uaçá. Rev. de Antropologia, São Paulo : USP, v. 42, n. 1/2, p. 29-45, n.esp., 1999.

. O modelo e a marca, ou o estilo dos “misturados”. Cosmologia, história e estética entre os povos indígenas do Uaçá. In: SILVA, Aracy Lopes da; FERREIRA, Mariana Kawall Leal (Orgs.). Antropologia, história e educação : a questão indígena e a escola. São Paulo : Global, 2001. p.196-208.

. Os povos indígenas do Uaça : Karipuna, Palikur e Galibi-Marworno - Uma abordagem cosmológica: o mito da cobra grande em contexto. São Paulo : USP, 1996. 54 p.

; SILVEIRA, Luís Fábio; LIMA, Renato Gaban. A pesquisa sobre a avifauna da bacia do Uaçá : uma abordagem interdisciplinar. In: SILVA, Aracy Lopes da; FERREIRA, Mariana Kawall Leal (Orgs.). Práticas. pedagógicas na escola indígena. São Paulo : Global, 2001. p. 287-59. (Antropologia e Educação)