Canela Apanyekrá

- Self-denomination

- Where they are How many

- Linguistic family

Canela is the name by which two Timbira groups have become known: the Ramkokramekrá and the Apanyekrá. There are significant differences between these neighbouring groups, but both speak the same language and have many of the same cultural patterns. Until the 1940s, the Ramkokamekrá had less contact with the national society and with other indigenous groups than the Apanyekrá. After that, the situation became the reverse. However, both groups have been strongly affected by several contact agencies, especially the Funai, ranchers and missionaries. On the other hand, both groups have sought to recover their autonomy in productive activities and to maintain the vitality of their culture, expressed by a conplex ritual life, shamanic practices and an intricate social organization.

Name

The Canela are composed of five surviving nations of the Eastern Timbira, the largest being the Ramkokamekrá, descendants of the Kapiekran (as they were known until 1820). The name Canela was also utilized by people of the interior for the Apanyekra, and for the Kenkateye, who were massacred and dispersed in 1913. The Kenkateye separated from the Apanyekra around 1860.

The Ramkokamekrá group presently uses the Portuguese name Canela to refer to themselves. Ramkokamekrá means "Indians of the almécega [gum tree] grove". They use the term Me(n)hi(n) to refer to the Eastern Timbira.

Probably the name Canela is a reference to the fact that these Indians are visibly taller - with their long legs -, when compared to the regional population and their neighbors, the Guajajara.

The Apanyekrá call themselves by this name. They are known in the literature only by this name and its orthographic variations, or even by Apanyekrá-Canela. Apanyekrá means "indigenous people of the piranha". Nimuendajú supposed that they were called by this name because they painted their lower jaw red, recalling an image of this carnivorous fish.

Language

The Canela and the Krahô speak the same language of the Gê family, Macro-Gê trunk, with small variations. The Canela understand the Krikati/Pukobyé with ease and, certainly, the Gavião of the Tocantins. These are the principal eastern Timbira languages that have survived. Apinayé (western Timbira) is as different from Canela as Spanish is from Portuguese. A Canela does not understand Xavante (central Gê) or Xokleng (Southern Gê), and has great difficulty in undertanding Xikrin (northern Gê).

Many Canela are able to expresss themselves in Portuguese, even if they don't speak it correctly. The Ramkokamekrá have a greater command of this language than the Apanyekrá. Among them, the men speak better Portuguese than the women, since they have more experience in the cities and in commerce.

In the Canela language, aspects of dualism are explicit, to the extent that almost all verbs possess two basic alternate forms. Besides that, when a person speaks to his own group, he uses an exclusive pronoun in the first person plural, me(n)pa (we-our group); but when he speaks to someone of another group, he uses an inclusive pronoun in the first person plural wa me(n) (we, all of us), as in Portuguese. Pronouns, adjectives, and substantives are not differentiated by gender, as in Portuguese, but a feminine or masculine suffix (-kahãy or -tsu(n)m-re, respectively) can be added to any substantive. There are two forms of pronoun in the second and third persons. The form -ka is used for kin, spouses, informal friends, and the majority of other individuals, including members of other Timbira tribes. The other pronoun, yê, is used to establish social distance and respect with the majority of affines and all formal friends. This last form is also used in the second and third person plural. Of the 30 phonemes in Canela, 17 are vowels, two are semi-vowels, and 11 are consonants. This produces an uncommon number of meaningful vocalic sounds. The language of the Canela does not posses dipththongs, but makes a phonemic distinction between long and short vowels.

Location

The principal Ramkokamekrá village, Escalvado, is known by the people of the interior and of the city of Barra do Corda as Aldeia do Ponto [Village of the Point] and is located around 70 kilometers south-southeast of this city, in the state of Maranhão. The demarcation of the 125,212 hectares of Canela Indigenous Land took place between 1971 and 1983. Today, that Land is ratified and officially registered. Until recently, these lands which consist of cerrado [vegetation typical of the Northeast, savannah-like], galley forests, and small plateaus, were located in the municipality of Barra do Corda, but now are located in the new municipality of Fernando Falcão, which came into being as a result of the growth of the old town of Jenipapo dos Resplandes. The southern limit of the Indigenous Land is in large part delimited by the Alpercatas mountains. The Corda River flows outside the Indigenous Land, about 20 kilometers away, along the northwest border.

With regard to the Apanyekrá, the legal regulation of the Porquinhos Indigenous Land, with a total area of 79,520 hectares located in the municipalities of Fernando Falcão and Grajaú, was done in the beginning of the 1980s. The principal village is located about 80 kilometers southwest of the municipality of Barra do Corda and 45 kilometers to the west of the Ramkokamekrá of Escalvado. It is to the east of the municipality of Grajaú, separated by 75 kilometers of easily passable scrub forest.

While the Ramkokamekrá basically live in areas of scrub forest [cerrado]with small streams, the Apanyekrá area is characterized by this same environment to the east and south but has extensive forests to the north and west. It also has the Corda River, which at some points is eight meters wide. The Apanyekrá area thus has the advantage of having the best soil for swidden agriculture and a greater abundance of fish, as well as game animals in the forest and the cerrado.

Demography

It is estimated that, before contact with the "whites", the Timbira nations lived in groups which totalled between a thousand and 1,500 people. The smaller groups faced problems in defending themselves during seasonal wars (June to August). The larger groups split up probably because of conflicts between leaders. Around 1817, the Kapiekran (ancestors of some Ramkokamekrá) were drastically reduced because of intertribal wars and smallpox. The survivors fled into the mountain valleys, but they returned to their present-day lands during the 1840s, there being no record of their population at that time. Nimuendajú counted around 300 Ramkokamekrá in 1936 and William Crocker, around 412, in 1960. Later censuses have recorded 437 (1970), 508 (1975), 600 (1979) and 836 (1988). In 1998, Funai recorded 1,262 people and, in the year 2000, 1,387. In 2001, Crocker and Pareschi counted 1,337.

As for the Apanyekrá, Nimuendajú estimated a population of 130 individuals in 1929. Crocker counted 205 in 1970, 213 in 1971, and 225 in 1975. A Funai report in the year 2000 gives a total of 458.

History of contact

The Kapiekran, ancestors of the Canela, were indirectly contacted by military forces at the end of the XVIIth Century, but only during the last decade of the XVIIIth Century did there effectively occur any incursions on their population and way of life. Periodic attacks were made by local militia and bandeira expeditions organized to sieze the lands of the Kapiekran, which were used for agriculture and cattle raising along the Itapicuru and Alpercatas rivers, to the northeast and west of Picos. Decimated by these wars, in 1814, the Kapiekran surrendered to the Brazilian forces of the region, in Pastos Bons, in exchange for protection. Their survivors, as well as those from various other Timbira nations, were authorized to settle in the northwestern corner of the ancestral lands of the Kapiekran. At the end of the 1830s, they occupied around 5% of the old gathering areas of the Kapiekran.

Then followed about a hundred years of relative peace and limited contact with people of the interior, until, in 1938, the Indian Protection Service (SPI) sent an agent to live with his family near the Ramkokamekrá village. This relationship caused rapid cultural change. Nimuendajú's fieldwork for his great study on the Canela, The Eastern Timbira, was undertaken, fortunately, before this process began, during six visits between 1929 and 1936.

The SPI obtruded in such a way on the indigenous authorities that the age-class leadership, essential for guaranteeing annual labor in family gardens, ceased to function. This weakening of leadership contributed significantly to the loss of self-sufficiency in agricultural production, even to the present day.

Cultural traditions also did not escape unharmed as a result of contact. In 1951, an important Ramkokamekrá chief, Hàk-too-kot, a great specialist and promoter of Canela traditions, died. At the same time, the teaching of writing began. In the 1970s, the incipient health assistance provided by Funai increased the Indians' confidence in pharmaceutical treatments, which proved to be favorable to population growth. Then, missionaries from the Wycliffe Bible Translators translated the New Testament to the Canela language and thus began preaching new values among the Ramkokamekrá.

The millenarian movement which occured among the Ramkokamekrá in 1963 also contributed to their disbelief in ancient traditions. The failure of the movement only exacerbated this disbelief, besides forcing them to be transferred temporarily to a Guajajara area near Barra do Corda, in order to escape the vengeance of the ranchers. This forced change to an adverse ecological zone exposed them to distinct types of agriculture and hunting, as well as to living together with the Guajajara, a Tupian group, and with the Brazilian urban culture.

The bridge built over the Alpercatas River in 1956 made it possible for relatively cheap commercial goods to be introduced among the Ramkokamekrá. Such merchandise was another important factor in their change of values, stimulating a greater investment in agricultural labor directed at obtaining these goods and favoring individual material wealth. In the 1990s, a project designed to help the Ramkokamekrá get through the period of hunger which preceded the harvest stimulated the clearing of large community gardens and convinced them that, by working together, they could increase their production. This, in turn, would be sold in the city in exchange for industrialized goods, their new cultural focus.

The first mention of the Apanyekrá goes back to the end of the first decade of the 19th Century, when they are mentioned by the military officer Francisco de Paula Ribeiro. It seems that they inhabited the mountainous area to the west of the Kapiekran, located far to the north of the trails through the river valleys utilized by the Brazilian colonists (through the Itapicuru and lower Alpercatas, and through the Parnaíba and Balsas river valleys). They thus suffered fewer attacks by hired gunmen, since they were less exposed than the Kapiekran, who inhabited the more level lands to the east and south along the Itapicuru and lower Alpercatas. At the beginning of the 1830s, the fertile lands of the headwaters of the Corda River and surrounding areas were occupied by a cattle-raising family. Thus the Apanyekrá came to live with the Brazilian inlanders who lived immediately to the south, which did not happen with the Ramkokamekrá.

The Apanyekrá have stories which probably date to the 19th Century, which tell of a time when they were subject to the strong control of a local rancher. He employed them on his ranch and in household chores. His gunmen slept with their women. The rancher would provide cattle for the festivals, in which everyone danced in the style of the backlands (embraced).

Around 1950, the SPI began to pay na inlander to live with the Apanyekrá and set up a post there. In contrast with the employees of the Ramkokamekrá post at that time, the head of the Apanyekrá post was more respectful and discrete in relation to the Indians, and protected them from the ranchers. The Apanyekrá continued to move their village periodically to different places on their lands, taking with them the "elementary post" and the head of the post. I found their village in the area of Águas Claras in 1958, Porquinhos in 1960, Rancharia in 1966 and 1971, and in another place in the area of Porquinhos in 1974 and 1975. They have not moved from Porquinhos since then, staying near the new post of the Funai and the building with school and infirmary, both built in brick and tile at the beginning of the 1970s.

In 1963, when the ranchers attacked the Ramkokamekrá, who were then engaged in a messianic movement, they also threatened to take the lands of the Apanyekrá. The threats continued and some peripheral lands were occupied by a rancher, who took the military engineering garrison at Barra do Corda to clear a landing strip in the area of Porquinhos around 1965, in order to protect the Indians.

The Apanyekrá were more isolated than the Ramkokamekrá not only because they were more distant from Barra do Corda, but also because the forests along the Corda River cover almost continuously the area between the city and Porquinhos, making the construction of a road directly between the two difficult. The road from Barra do Corda to the Ramkokamekrá, by contrast, crosses through only areas of brush and scrub forests and needed only a bridge, which was built in 1971. Around 1978, trucks which went from Barra do Corda to Porquinhos had to go first south to the Ramkokamekrá village of Escalvado/Ponto, in such a way as to cross the scrub forest near the headwaters of various waterways of the area over newly-constructed bridges in order to reach Porquinhos.

Political organization

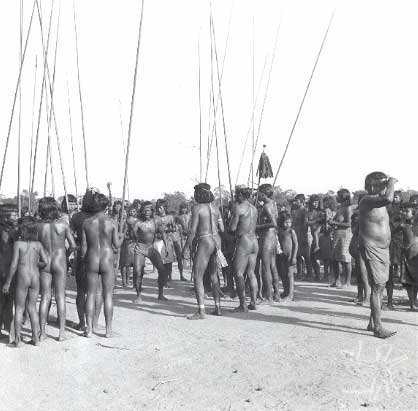

None of the systems of moieties and cerimonial societies existing among the Canela are exogamic, although this cannot be stated with certainty in relation to the Canela of the XVIIIth Century. The age classes - of lifelong affiliation - are formed and initiated through four cerimonies. Each age class consists of men born in periods of about every ten years. Consecutive age classes sit on opposite sides of the plaza, east or west.

Thus, age classes of men around 10, 30, 50, and 70 years of age sit on one side; while men around 20, 40, and 60 years of age sit on the other side. Nearly all activities are undertaken by these moieties, or by opposed age classes, competing amongst themselves: cerimonial or daily dances and chants, flat races or log races, as well as the clearing of gardens, collective hubts for cerimonies, clearing of roads or trails along the dividing line of the Indigenous Land. Every 20 years (tem years among the Apanyekrá), the western class - whose members are approximately 50 years of age - tradkitionally moves to the center of the plaza, being the eldest, the pro-khãm-mã (mikhá for the Apanyekrá). The eastern class, in turn - whose members have just turned 50 - join them, thus forming the council of the elders. The men of the eastern half give counsel, but they do not govern.

The council of the elders used to select the chief, who would normally govern for the rest of his life. Today, he is kept in the position for six months to two years. The chief is in charge of external relations and assumes the greater part of internal initiatives. The council of the elders generally supports him, but it can exercise subtle opposition and block or alter unpopular decisions. The special function of the elders is to plan and conduct the lengthy festivals.

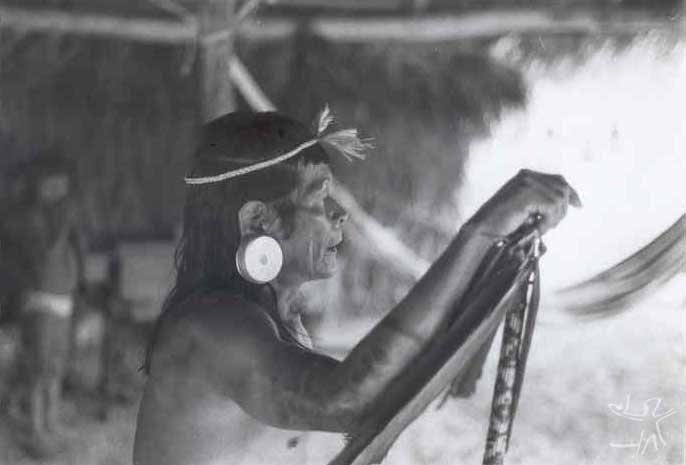

The Canela are famous for the value that they give to internal peace in the group. Words of anger should not be expressed in the central plaza of the village, where the eldest men meet twice a day to settle problems and reaffirm sociability. If internal quarrels of the extended families are not put forth there, they will be discussed and settled in one of the great houses located in the village circle, where the uncles of the complainant and accused act as representatives of their nephews and nieces. Village leaders and most individuals avoid making controversial questions become public. The cylindrical ear ornaments used by the men were seen as instruments to enhance hearing and, consequently, obedience.

Different from the Ramkokamekrá, who had a main chief (except during the split which occured between 1957 and 1963), the Apanyekrá had three chiefs during the 1950s and 60s. One took charge of daily situations with great efficiency, but he couldn't be the main chief because, they said, he was of Kenketeye descent. Less efficient as a coordinator of activities, although with greater prestige, was the director of the rituals, a great leader in songs and maracá dances and a prodigious storyteller. The oldest chief was the principal intermediary with the SPI in Barra do Corda and made monthly journeys there to receive an insignificant salary.

Family life

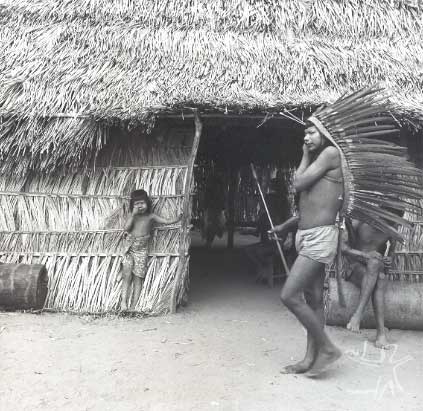

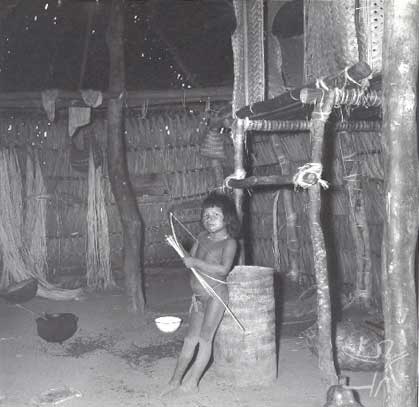

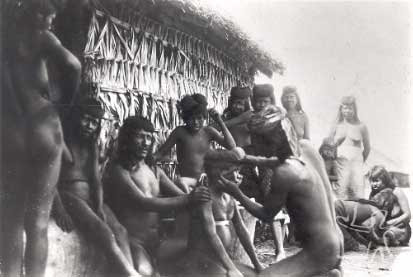

The Canela live in palm thatch or mud houses, in the backlands style, built around a great circular path of approximately 300 meters in diameter, including the small yards behind each house. There is a plaza of about 75 meters in diameter in the center, and, like radii of the circumference, trails lead from the central plaza to each house. Behind most houses, there are located others of the same family, forming a second row and, at times, more distant houses begin a third row. (see photo in the section Location).

A woman - with her sisters, mother, grandmother, and daughters - lives in the village circle in an area defined in relation to the sunrise, and always in the same position in the sucessive locations to which the village is moved. Their cousins, descendants of the same ancestral woman in the female line (parallel cousins), live in adjacent houses along the circle of the village. If they are of the same generation, she treats them as "sisters". This woman calls the mothers of her "sisters", "mother", and the daughters and sons of her "sisters", "daughters" and "sons.". The arc of contiguous houses in which these women live is called a "long house" (ikhre lùù).

A woman's sons and brothers marry out of their "long house" and out of the house where their fathers, their mothers' fathers, and their fathers' fathers are from, in order to avoid incest. The sons and daughters of these men are cousins of the sons and daughters of their sisters, who stay in the house where they were born; more exactly, they are cross-cousins, since their fathers are opposite sex siblings. In this system of relations, a man or a woman calls his father's sister's son (who lives outside his "long house"), "father". In the same way, a man calls his mother's brother's son, "son". A woman calls her mother's brother's son, "nephew", and his sister, "niece". Grandmothers and grandfathers are terminologically equated to father's sisters (aunts) and mother's brothers (uncles), respectively.

Although the Apanyekrá and the Ramkokamekrá had kept up until then the same pattern of kinship terminology, at the end of the 1950s, the Apanyekrá abandoned the use of the term "father" for father's sister's son and for father's sister's daughter's son. In either case, the individuals was called "uncle" or "nephew", according to the new determining principle of relative age. Besides that, Apanyekrá kinship was less determined by "blood" (kaprôô) relations and tended to be more based on convenience or preference.

Kinship is recognized bilaterally, despite the matrilateral emphasis. There are no clans. There is only a certain number of isolated and cerimonial lineages whose function is to transmit the right to perform certain roles.

In the case of the Apanyekrá, various exceptions have been recorded to the pattern of matrilocal residence. By contrast, whatever exceptions occured among the Ramkokamekrá Canela were explained to me as being temporary.

Relations between the sexes

A first marriage occurs when the girl is around 11 to 13 years old and gives up her virginity to the man whom she likes. Nevertheless, she is not definitively married until she becomes pregnant and gives birth to a child. Before 1975, marriage was practically indissoluble, but nowadays, when a man leaves the house, which is frequent, it's called "divorce of the children".

During the seclusion, which lasts some 40 days after birth, the woman calls her "other husbands" to take part in the ritual together with her effective husband. As she could have practiced serial, cerimonial sex with several dozen men during pregnancy, she identifies from one to four of these "other husbands" as those who contributed with a sufficient quantity of semen for the formation of the fetus. These men should observe food and sexual restrictions in such a way as to favor the growth and health of the child. If not, the life of the child is put at risk. Presently, there is no longer identification of these other husbands, but the belief persists. Consequently, in order to guarantee the health of the baby, another principal "husband" is secretly advised about the necessity of observing food and sexual restrictions, without his actual wife knowing anything about his transgressions.

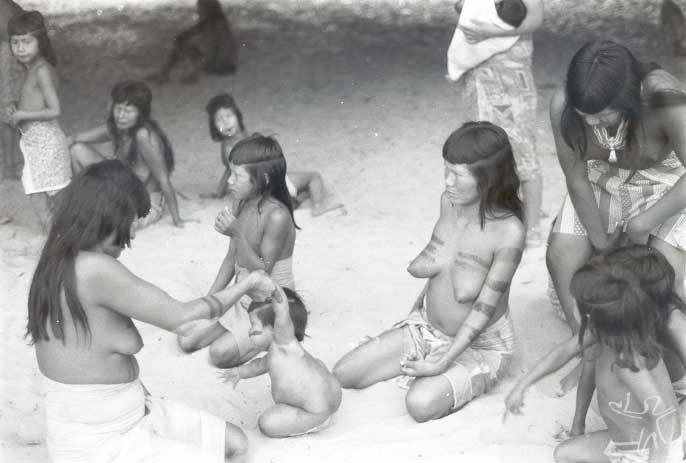

The children are raised in the house of the mother and mother's sisters and all her children. Before more intense contact with Western patterns of sociability, it was common for the woman to leave her children with her mother or one of her sisters while she would be off on a love affair.

In this way, formal friends could have sexual relations. This activity was so widely practiced that it constituted a very common form of recreation. Extra-marital sex was allowed to everyone - except consanguineal relatives, formal friends, and certain affines - during its serial practice, as the innumerable annual festivals required. Thus, depending on the occasion, a group of ten to 80 men could have sex - one at a time - with a group of two to eight women. Among individuals, publicly or privately, to refuse the sexual desire of a man was difficult, for such an attitude was seen as selfish and anti-social, and even mean. Men and women thus had to be generous as much with their bodies as with their few possessions such as baskets, bows, arrows and food.

Kinspeople (such as uncles and nieces, or aunts and nephews) who did not live in the same house, and had no name-ties or prescribed behavior, played and joked when they met. However, very distant kin could break the incest tabu and then treat each other like "spouses". Nevertheless, this uncommon sexual generosity was totally lost in the mid-1980s, as a result of the intensified contact with non-Indians and when industrialized goods came to be more easily acquired and strongly desired. The old times of pleasure were thus lost due to sexual jealousies on the part of the husbands.

In the social sphere, the Canela have five systems of moieties and, exclusively among males, six groups of the central plaza, five ritual associations, two hierarchical orders and five groups of men who are of inter-tribal origins. The women do not have associations, but almost all of the masculine groups have two girls selected as members of these male associations. The women get their own force in relation to the men through the control of their families and extensive kinship networks.

Although the power between the sexes was balanced in favor of the men, the situation of the women grew in strength in the latter half of the XXth Century. Today the women can also be painted on the central plaza like cerimonial chiefs. The power of the men is best considered when orders and initiatives come from the chiefs and the elders. Male power has its basis in the meetings on the plaza and affects all the members of the village. In compensation, the power of the women is demonstrated exclusively within the house, through the control over the distribution of food to all the inhabitants of the village.

Although the power between the sexes was balanced in favor of the men, the situation of the women grew stronger in the latter half of the XXth Century. Today the women can also be painted on the central plaza like cerimonial chiefs. The power of the men is best considered when orders and initiatives come from the chiefs and the elders. Male power has its basis in the meetings on the plaza and affects all the members of the village. For their part, the power of the women is demonstrated exclusively within the house, through the control over the distribution of food to all the inhabitants of the village.

Formal friends and naming

The Canela compare formal friends to godfathers and godmothers or the godparents of a wedding, relationships which are common in the interior. There is a special respect between these men and women, who should be reciprocally served, honored, and protected. For example, if a baby accidentally falls into the fire, its principal formal friend should act out the accident in front of the baby's parents, with the possibility of burning himself in the same way. This dramatic act embarasses the parents in front of the assembled crowd, in such a way that father and mother will try to prevent the accident from happening again with their baby. Formal friends, almost always men, joke amongst each other when they meet. Each one chooses his formal friend in the period of initiation of his age class. In the past they were inseparable. They went to war together, they protected each other mutually, and on occasion they exchanged wives.

In relation to naming, a man gives his set of names to his sister's or classificatory sister's son, while the woman gives hers to her uterine or classificatory brother's daughter. Thus, a brother and sister, uterine or classificatory, name their nephews and nieces of the same sex. During the 70s, there was a greater exchange of names between classificatory opposite sex siblings than between uterine siblings. It makes more sense for classificatory siblings to proceed in this way, since this institution narrows the relations between two people. The uterine siblings already have a strong relationship, thus the exchange of names doesn't serve to reinforce it. An alternative form of conduct open to distant cousins of opposite Sex who call themselves "brothers/sisters" is to have sexual relations, which makes them classificatory spouses, consequently breaking that relation. But if, instead of doing that, they exchange names, they will become almost as close as uterine siblings.

Along with name transmission goes the cerimonial rites and access to roles. Among other Timbira and the northern Gê, name transmission is cerimonially more important, when the name-giver transmits his cerimonial persona to the receiver. Among the Canela, however, name transmission is less evident and significant, both in cerimonial practices and in the daily life of the individual. This happens because the presence of the system of age class moieties is much more notable than the systems constituted by units based on name transmission. There are roles that have nothing to do with name transmission; for example: leaders related to age classes and young girls associated with initiation rites, wè tè girls, visiting intertribal chief, or member of the group of clowns.

The Apanyekrá had more formal friends related to the personal name than the Ramkokamekrá, but they did not have, as the Ramkokamekrá did, the ritual (intêê) to make new formal friends. An Apanyekrá person is buried by his/her affines. Among the Ramkokamekrá, it is the formal friends who do this.

Productive activities

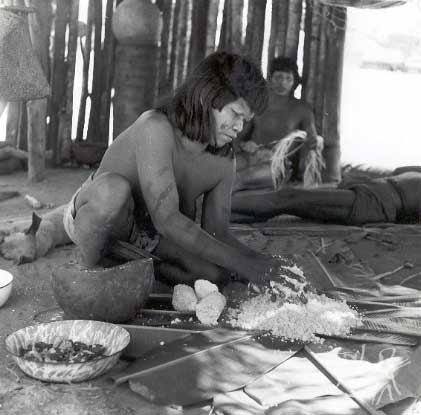

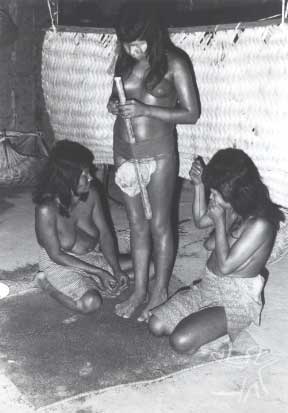

Canela traditional harvests include peanuts, corn, sweet potato, yams, pumpkin, feijão-de-corda (Phaselous sp.), bitter manioc (wayput-re), sweet manioc, cotton, gourds and other produce. The most common products today - manioc, rice and beans - were adopted after contact with the national society, as were bananas, oranges, mangoes, watermelon, pineapple, papaya, tobacco, sugarcane and other items.

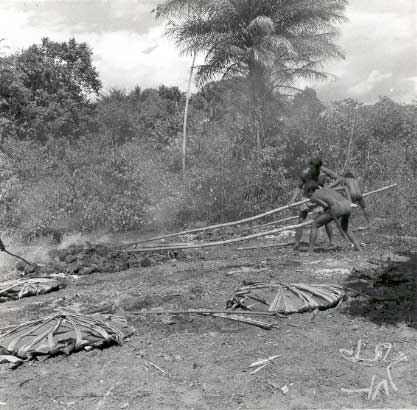

Among the Ramkokamekrá, in the small galley-forests of their lands, riverside gardens used to be cleared with stone axes and burned. These traditional gardens produced less than 25% of the food consumed, while gathering, fishing, and hunting supplied the rest. At the end of the 1830s, the relocation of the Canela in areas which represented about 5% of the lands that they used to occupy forced the Canela to practice more extensively the system of swidden agriculture, following the regional model, in order to obtain greater quantities of food products.

At the end of the 1940s, the economy of both groups became deficient, depending on outside support in order to maintain itself. The Canela came to depend significantly on the food supplies provided by the indigenist agency and to practice the system of "halving" with non-indigenous peoples, working on their lands in order to keep half of the production. In the beginning of the 1990s, however, among the Ramkokamekrá the gardens came to supply sufficient food for their survival, without need of the system of partnership, which they saw as an humiliating experience. They continue, nevertheless, to suffer from na insufficient production during the lean months from September to December. The gardens begin producing in January, and the height of production occurs with the rice harvest in the month of May. Já os Apanyekrá não alcançaram esse retorno à auto-suficiência, entretanto mantiveram mais plantas nativas que os Ramkokamekrá e cultivavam suas roças de modo menos influenciado por métodos sertanejos.

The challenge faced at the moment by the Canela Ramkokamekrá is one of guaranteeing sufficient food production in such a way that the kinds of food available don't come to an end in September. Thus, they wouldn't have to consume the first manioc tubers, after only a year of growth, and hence little developed. With a sufficient production of manioc, they could consume only the tubers cultivated two or three years before. Several families have been trying to produce a surplus which can be commercialized with the non-indigenous people of the interior or in the markets of the cities.

Fortunately, for the time being the riverside forests on the Indigenous Land present a possibility for producing sustenance for the the Ramkokamekrá population which has been expanding for some time, through the practice of swidden agriculture. An additional source of funds is the pensions for retired people from Funrural, which has become a significant form of economic aid ever since the 1980s. Besides that, there are several people who are retired for health reasons, mothers who receive aid, and students with educational fellowships in the village of Escalvado. In addition, in 2001, there were 8 Ramkokamekrá Indians employed by the Funai (the National Indian Foundation), 3 by Funasa (the National Health Foundation) and four indigenous teachers in the municipality.

Traditionally there was a tendency for sisters to make their gardens in the same area, following the pattern of the extended house in the village. However, politically motivated men try to attract male followers to their garden areas. Thus, factions are formed, although the Canela are discrete as far as political rivalries go. The power of potential chiefs emerges, nevertheless, from the "direction" of a garden place.

Presently, there are two large "garden communities" in the Ramkokamekrá group, each with a circle of houses, which house 80% of the population. There are also at least four smaller groupings. Even so, each family has a house in the main village, Escalvado, and it is to the village that they return for the annual festivals. Lately, however, there has been a movement back to the village on the part of the families who have children who regularly attend the school in Escalvado. These families spend more time in the main village, and only go every now and then to their gardens to get vegetables.

Arts

Canela art is best expressed in their musical forms, as well as in their dances accompanied by songs. The daily cycle of the Canela includes three periods of sung dances, which go from 2:30 to 5:30 in the morning, approximately, from five to six in the afternoon and from seven to ten at night, although rarely does the same person complete the entire round of seven hours of recreation. This cycle occurs only when the Canela are assembled and living together in the main village, and not dispersed in the garden villages or involved in partnerships with neighboring dwellers. The Apanyekrá song and dance to the rhythm of the master of the rattle is almost identical, in form and time of day of its performance, to the Ramkokamekrá version. Only the musical style of the songs sounds a bit different to the listener. The Ramkokamekrá songs stress harmonic sequence, while the Apanyekrá songs give greater emphasis to the melodic line.

The men walk around, showing off and jumping in front of a long line of women, all led by a man who sings and dances with a rattle. These days, this dance only takes place during the times of the great festivals.

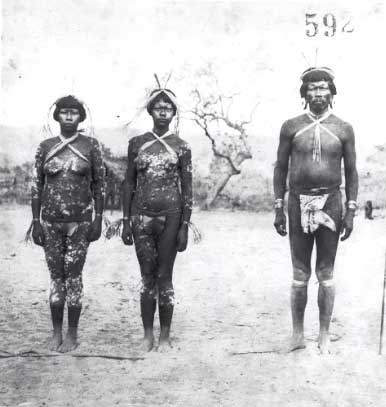

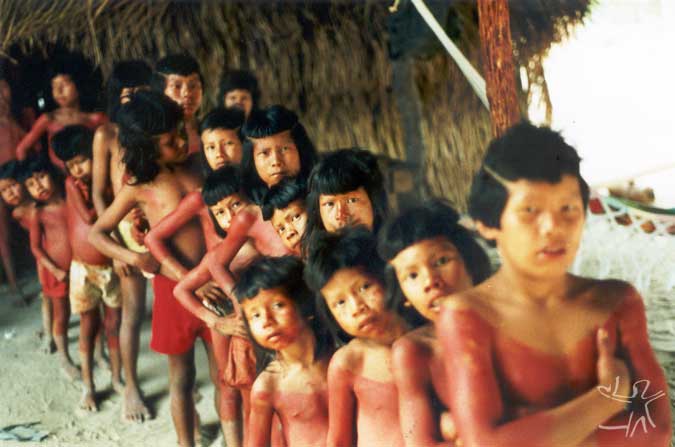

Their visual arts are relatively simple, especially if compared to their "cultural cousins", the Xikrin (a Kayapó subgroup), for whom body painting is well developed and refined. Among the Canela, urucu is applied to the body to the body in familiar situations, of happiness and health. Carbon, when fixed with latex from the "milkwood" and applied in na ordered way to the body is a familiar manifestation; when applied to the skin in a crude and disorderly way it indicates that the individual was recently involved in na extra-maritual relation. The blue-black paint of the jenipapo is used only in a specific cerimonial situation, never on day-to-day occasions.

On the occasion of solemn cerimonies, the Ramkokamekrá group adorn themselves with hawk down (today substituted by domestic duck feathers) glued on the body with the resin of almécega gum and used with red urucum dye in precise patterns. In the case of the Apanyekrá, they add green parakeet feathers. Apanyekrá material artifacts are basically the same as those of the Ramkokamekrá, although the styles are a little different.

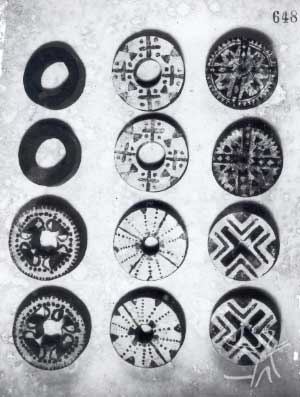

The Canela used to make approximately 150 types of artifacts, most of which are male body ornaments, many being made especially to be used in specific cerimonial roles. The materials used are mainly from the leaves of the buriti and inajá palms, as well as the little tucum palm. The men carefully sculpt the tips of staffs and spears made of brazilwood, which were used in the past for warfare but today are generally decorated with parrot, macaw, and other bird feathers. Various types of gourds were used as utensils; most, however, have been substituted by merchandise from the city. They used to make various kinds of mats and baskets, but they didn't have ceramics. The Canela often practice, with a moderate competitive spirit, a race with heavy logs weighing up to 120 kilos, over distances of up to 10 kilometers. They also have short, flat races and other, longer ones of up to a thousand meters.

Religiosity and Shamanism

According to Canela tradition, the soul would go to a village of souls some place in the west, where it would live in a situation similar to life in a village, with the difference that things were bland and less pleasing. For example, the food was less tasty, the water was lukewarm but not cold, and sex was less pleasurable. After a certain time, the spirits turned into game animals, then smaller animals, and finally, something like a mosquito or a treestump. According to Canela tradition, after death the soul goes to a village of souls some place in the west, where it lives in a situation similar to life in a village, with the difference that things were bland and less pleasing. For example, the food was less tasty, the water was lukewarm but not cold, and sex was less pleasurable. After a certain time, the spirits turned into game animals, then smaller animals, and finally, something like a mosquito or a treestump. Finally, the entity ceased to exist.

Souls that still retain their human form can be contacted by shamans. But if someone has a chance encounter with them, that individual could become seriously ill or even die. The Canela believe that, if they break certain rules, such as going to the forest at night or getting water from the stream after dusk, the souls can get them. In any case, souls bring harm to humans, and only shamans can discover what they have done.

It is believed that, some time ago, powerful shamans had extraordinary supernatural power, essentially that of omniscience - knowledge and prevision of everything. That, however, was only possible with the aid of the souls of recently deceased, most of whom were great shamans when alive. The good shamans would summon a soul which would tell them all that they needed to know. For example, if a woman's newborn died, the shaman is able to say why that happened, which is probably attributed to "bad [heavy]" and consequently polluted food. Several shamans would have seen and told others, who in turn would have reported the fact to the interested shaman. The diagnosis of the shaman is definitive, even though the mother may have another version. His decision is never disputed.

The shamans do not compete for power with the political chiefs. Many chiefs have had some shamanic power, but never as great as that of a good shaman. The shamans cure patients through the extraction of sickness or pollution, and are remunerated only when successful. On rare occasions, women become shamans but, in the 1970s, there were several women shamen and at least two received a place in their mythology.

The shamans cure patients through the extraction of sickness or pollution, and are remunerated only when successful. There are also anti-social shamans, who can cast evil sorcery, which enters the body as sicknesses. Other shamans struggle to remove the sorcery, seeking to send it back. In the past, an anti-social shaman, accused by the village council of homicide by sorcery, was clubbed to death with sticks. The last time that this happened was around 1903.

To undergo food and sexual restrictions is a means for the individual to become strong in character and skill, and so that he can develop, through personal effort, the skills for the principal careers - hunter, runner, or shaman -, but not to dance and sing with the maracá.

The Canela believe that pollution penetrates the body through the ingestion of meat soups and by means of contact with sexual fluids. Such pollutions do not affect a healthy person, however they weaken the powers of a warrior, hunter, runner, or shaman. Nevertheless, if an individual is sick, or weak, as in the case of a baby, common pollutions can make him become sicker, or even kill him. The Canela believe that the blood of the parents, uterine siblings and children of an individual is very similar to one's own. Thus, this nuclear family is so interconnected that the pollution of one of its members can affect the others. If they are already in a more vulnerable situation, these additional pollutions can make the individual sick or kill him. So, when someone of a person's nuclear family becomes sick, he or she has to submit to sexual and dietary restrictions in order to help in the recovery of the sick.

An individual becomes a shaman after receiving the visit of one or several souls, during a serious sickness, when the souls come to cure the dying person. A young man who wishes to become a shaman must undergo an intensive process of dietary and sexual restrictions, in order to prevent the penetration of contaminating elements into his body. He can also ingest certain infusions of herbs that eliminate polluting elements. Souls are attracted by the individual who is free of polluting elements. When they find such a person, they visit him and give him the powers to be a shaman. Generally the powers are specific for curing certain bodily intrusions, like snake bites, but, for the great shamans, such powers can be applied more generally.

In summary, the Canela traditionally possessed various forms - supernatural, natural and human - of strengthening their life conditions. First, the shamans could communicate with souls when they needed information and powers. Second, a source of strength in general derives from the singing of certain songs during specific festivals. Third, a Canela could observe sexual and dietary restrictions in order to keep pollution away from his body and thus, achieve certain capacities. Fourth, it was also possible to snuff certain infusions in order to increase his skills as hunter and improve his health conditions in general.

The Ramkokamekrá believe that the Apanyekrá shamans are more powerful as curers, such that they often seek their cures. In the mid-70s, the universe of the spirits and the dangers of pollutions were given more credit among the Apanyekrá than among the Ramkokamekrá, and the Apanyekrá also observed the restrictions more seriously.

Since 1830, the Canela have taken part in the practices and beliefs of popular Catholicism. Since 1970, the number of Ramkokamekrá who say they are "believers" (protestants) has been growing, in 1993 it reached 25% of the population, but in 2001 this number had diminished to 15%. By contrast, the Apanyekrá have always had less contact with Protestants.

Mythology

In the past the Canela had more than a hundred myths, but today they do not fully believe in them, with the exception of a few who still believe in the myth of Awkhêê. This being had supernatural powers and, at will, transformed into animals or other forms, frightening his uncles who then tried to kill him. Although they believed they had burned him in a great fire, he survived in the form of ash. On returning to human form, whether as Awkhêê or as Dom Pedro II, the Emperor of Brazil, he informed the Canela that they had to choose between their world, represented by the bow and arrow, and the world of the civilized whites, represented by a firearm. The Canela chose the bow and arrow and, as a result, were left in a subordinate position in the world of the whites. Thus, the peoples of the interior had to help the Canela and give them everything for free. In exchange, the Canela owe respect, deference, and obedience to the Whites. That is why today various Canela still expect to receive food and equipments as gifts from Brazilian citizens, foreigners and NGOs, instead of using their own efforts to solve the problems they confront.

Other Canela myths explain the origin of fire and corn: a boy brought fire for his people after having stolen it from the hearth of a female jaguar. Star Woman fell in love with a Canela and so came down to live for awhile among his family members. During this stay, she indicated that corn would grow in the forest and she taught them that that was good to eat. This was the origin of gardens. She then returned to the sky with her mate and both transformed into twin stars, known among us as Castor and Pollux.

Parallel to a wide variety of myths about how they believe their ancestors lived, the Canela have a large number of war stories, some of which describe how they struggled against and were defeated by thfe Whites during the first half of the XIXth Century. Other stories tell how their chiefs then led them. Myths and war stories used to be told in the center of the village, to entertain the population at the end of the afternoon and in the early morning hours, but this practice was abandoned by the end of the 1950s. Today, when these stories are told, they make reference to "wild Indians", their ancestors, almost as though they were a different people. The great warriors, as well as the strong leaders, used shamanic powers to put their plans into effect. For example, the warrior Pèp shot arrows against enemies whose eyes he was capable of hitting directly, killing them. In the same way, important chiefs used their limited powers to attain their objectives, whether by exercising those powers, or by the fear of the population that they could do so.

An origin myth recounts that Sun and Moon walked over the land, creating the norms for social life. Sun established the norms favorable to life while Moon modified them to test its imperfections. Sun created ideal men and women while Moon created those with twisted hair, dark skin, and seen as deformed. Sun allowed machetes and axes to work by themselves in the gardens, while Moon made them stop. Consequently, men had to work hard to make their gardens - the origin of work. There are at least a dozen episodes of this myth which recount the beginning of death, floods, forest fires, and why the buriti palms are tall and the moon has its spots, besides other conditions.

Other Canela myths explain the origin of fire and corn: a boy brought fire for his people after having stolen it from the hearth of a female jaguar. Star Woman fell in love with a Canela and so came down to live for awhile among his family members. During this stay, she indicated that corn would grow in the forest and she taught them that that was good to eat. This was the origin of gardens. She then returned to the sky with her mate and both transformed into twin stars, known among us as Castor and Pollux.

Parallel to a wide variety of myths about how they believe their ancestors lived, the Canela have a large number of war stories, some of which describe how they struggled against and were defeated by the Whites during the first half of the XIXth Century. Other stories tell how their chiefs then led them. Myths and war stories used to be told in the center of the village, to entertain the population at the end of the afternoon and in the early morning hours, but this practice was abandoned by the end of the 1950s. Today, when these stories are told, they make reference to "wild Indians", their ancestors, almost as though they were a different people. The great warriors, as well as the strong leaders, used shamanic powers to put their plans into effect. For example, the warrior Pèp shot arrows against enemies whose eyes he was capable of hitting directly, killing them. In the same way, important chiefs used their limited powers to attain their objectives, whether by exercising those powers, or by the fear of the population that they could do so.

Although the origin myths of the Apanyekrá and Ramkokramekrá are very similar, there are some surprising differences. For example, Star Woman returns to the heavens with the Apanyekrá man only after having committed a hostile act of vengenace, pouring the content of a gourd on the plaza, which does not take place in her more friendly departure in the Ramkokamekrá version. For the Apanyekrá, Awkhêê has another name, Plùùkupê, but the order to submit to the civilized people and depend on them, which resulted from the fact of having received the bow and arrow instead of the firearm, is the same. Moreover, the Apanyekrá have a certain number of myths that the Ramkokamekrá do not have and vice-versa.

Rituals

The Canela have a set of ritual cycles based on the extended family, in which matri- and patrilateral kindred participate, although the former predominates. The principal rituals for both sexes happen at birth, puberty and marriage(several stages), the afterbirth restrictions (couvade) and mourning.

The rites of passage for adolescents consist of ear-piercing for the boys and seclusion for the girls, at the time of their first menstruation. Both sexes have post-puberty practices. The naming of babies, shortly after birth, is restricted to the name-givers; the birth of a male was announced by the name-giver.

Another set of ritual cycles occurs during the festivals and is based on the support and participation of almost the whole society. Boys are introduced as lifetime members into the age class through four or five initiation festivals. As the first step to marriage, the majority of the girls enter as associates in the male rituals, in such a way as to receive their maturity belts, which are necessary for being accepted by their affinal kin. This division by age classes trains the boys to become warriors, while sexual practice among the male societies helps the girls to accept and like extra-marital serial sex.

The holding of the Apanyekrá male initiation rites (Khêêtúwayê e Pepyê) has been irregular since the 1970s and, since then, these rituals have been held only twice in order to form an age class, instead of four or five times, as happens among the Ramkokamekrá. In the 1990s, the performance of these rituals among the Ramkokamekrá had also become irregular.

The Apanyekrá ritual that ends the summer (Wè tè) was not being held with regularity, and the ritual that begins the same season (also called Wè tè) seems never to have been practiced by them. The Apanyekrá equivalent (Krokrok) of the Ramkokamekrá ritual of the hawks (Pepkahàk) has been lost, and the ritual of the masks was never acquired by the Apanyekrá.

On the other hand, the rainy season ritual practices of the Red and Black cerimonial moieties were in a way more effective among the Apanyekrá than among the Ramkokamekrá, and the Apanyekrá version of the Laranja and Pàlrà rituals were similar to those of the Ramkokamekrá.

The Apanyekrá ritual of the fish (Tepiakwá) was not held for several years around the 1970s, but it was still very popular among the Ramkokamekrá in the 1990s. Transmission of ritual property (haakhat) through matrilineal descent found in several Ramkokamekrá cerimonies and of the rights to fill certain roles, especially in the ritual of the Fish, was not found among the Apanyekrá.

A notable difference between the two groups exists in the rituals to introduce young boys and adolescents into an age class. Among the Apanyekrá, the adolescents caught leaving their seclusion for conjugal or extra-conjugal encounters were lined up together with their sex partners, and made to kneel face to face on the plaza, in such a way that all publicly lived their shame. The severity of this punishment for the same transgression was not characteristic of the Ramkokamekrá, who did not punish the adolescents who committed this infraction.

Notes on the sources

On the older sources, Francisco de Paula Ribeiro, a Portuguese military officer, whose texts are published in the Revista do Instituto Histórico e Geográfico Brasileiro, provides the richest and most reliable information on the situation of the Canela and other Timbira and the conquest of their lands by the advance of cattle-raisers in the beginning of the XIXth Century.

As for ethnological studies, the first major work is The Eastern Timbira, by Curt Nimuendajú, who visited the Canela six times between 1928 and 1936.

William Crocker began his ethnological research with the Ramkokamekrá Canela in 1957 and has consistently returned to their villages up to the present day, such that his visits total more than 72 months of fieldwork. He has several Canela field assistants, who write or tape daily notes. Besides the first volume of his work The Canela (Eastern Timbira), he has published several articles on different aspects of the life of the Canela. Together with his wife, Jean Crocker, he has published a lighter book, The Canela: Bonding through Kinship, Ritual, and Sex, the purpose of which is to stimulate the interest of university students in ethnological questions.

The analysis of the messianic movement among the Canela in 1963, undertaken by Manuela Carneiro da Cunha, uses as sources the texts published by William Crocker.

Jack and Jô Popies, of the Wycliffe Bible Translators spent 22 years (from 1968 to 1990) among the Canela translating the New Testament to the native language.They were well-liked by the population and taught scores of young people to read and write in Canela.

The National Museum of Natural History, of the Smithsonian Institution, in Washington, DC, where William Crocker (now retired) worked, has a vast collection of material on the Canela: many photos, unedited 16 mm and super 8 films from 1970. In 1997, a video film was begun and finished in 1999. The author also has left in the Smithsonian written and spoken diaries in Canela and Portuguese, tape-recordings of songs (also in the US Library of Congress) and myths in Canela.

In Brazilian institutions, there are collections of Canela artifacts in the Museu Goeldi (Belém), in the Museu Nacional (Rio de Janeiro) and in the Museu Paulista (São Paulo).

The author collected less material among the Apanyekrá than among the Ramkokamekrá. He did not make any collection of specific artifacts of the Apanyekrá, although many Apanyekrá items may be found in the collections. No-one has taped Apanyekrá music with high quality equipment as was done among the Ramkokamekrá. Nor have diaries written by the Indians been collected.

The Master's dissertation by Maria Elisa Ladeira, The Exchange of Names and the Exchange of Spouses: A Contribution to the Study of Timbira Kinship, deals more with the Apanyekrá than with the Ramkokamekrá, comparing the first to the Krahô and the Apinajé.

Sources of information

- ADAMS, Kathlen; PRICE JUNIOR, David (Eds.). The demography of small-scale societies : case studies from lowland South America. Bennington : Bennington College, 1994. 86 p. (South American Indian Studies, 4)

- ALHO, Getúlio Geraldo R. Três Casas Indígenas : pesquisa arquitetônica sobre a casa em três grupos - Tukano, Tapirapé e Ramkokamekra. São Carlos : USP, 1985. 91 p. (Dissertação de Mestrado)

- CROCKER, William H. Canela (Central Brazil). In: WILBERT, Johannes (Org.). Encyclopedia of World Cultures. v.7. New York : G. K. Hall & Co., 1994, p.94-8.

- --------. Canela marrigage : factors in change. In: KENSINGER, K. (Org.). Marriage practices in lowland South America. Urbana e Chicago : Univer. of Illinois Press, 1984. p.63-8. (Illinois Studies in Anthropology, 14)

- --------. Canela relationships with ghosts : this worldly or otherworldly empowerment. Lat. Am. Anthropol. Rev., s.l. : s.ed., v. 5, n. 2, p. 71-8, 1993.

- --------. The Canela (Eastern Timbira), I : an ethnographic introduction. Washington : Smithsonian Intitution Press, 1990. 506 p. (Smithsonian Contributions to Anthropology, 33)

- --------. Estórias das épocas de pré e pós-pacificação dos Rankokanmekra e Apaniekra-Canela. Boletim do MPEG: Série Antropologia, Belém : MPEG, n.68, 1978. 30 p.

- --------. Extramarital sexual practices of the Rankokamekra-Canela indians : an analysis of socio-cultural factors. In: LYON, Patricia L. (Org.). Native South Americans : ethnology of the least known continent. Boston : Little, Brown ans Co., 1974. p.184-94.

- --------. A method for deriving themes as applied to Canela indian festival materials. Ann Arbor : Univ. of Wisconsin, 1962. 299 p. (Ph.D. Dissertation)

- --------. O movimento messiânico dos Canelas : uma introdução. In: SCHADEN, Egon (Org.). Leituras de etnologia brasileira. São Paulo : Cia. Editora Nacional, 1974. p.515-28. [Tradução do original em inglês publicado nas Atas do Simpósio sobre a Biota Amazônica, v.2 (Antropologia), p. 69-83, 1967].

- --------. Myths. In: WILBERT, J.; SIMONEAU, K. (Orgs.). Folk literature of the Gê indians. v.2. Los Angeles : Ucla Publications, 1984. p. 17-32; 50-2; 97-106; 195-203; 354-8.

- --------. The non-adaptation of a savanna indian tribe (Canela, Brazil) to forced forest relocation : an analysis of ecological factors. In: SEMINÁRIO DE ESTUDOS BRASILEIROS (1o.: 1971). Anais. v.1. São Paulo : Instituto de Estudos Brasileiros, 1972. p. 213-81.

- --------; CROCKER, Jean (Eds.). The Canela : bonding through kinship, ritual, and sex. Forth Worth : Harcourt Brace College Publishers, 1994. 202 p. (Case Studies in Cultural Anthropology)

- CUNHA, Manuela Carneiro da. Logique du mythe et de l’action : le movement messianic Canela de 1963. L'Homme, Paris : Ecóle des Hautes Études en Sciences Soc., v.13, n.4, p. 5-37, 1973.

- LADEIRA, Maria Elisa. Uma aldeia Timbira. In: NOVAES, Sylvia Caiuby (Org.). Habitações indígenas. São Paulo : Nobel ; Edusp, 1983. p. 11-32.

- --------. A troca de cônjuges : uma contribução ao estudo do parentesco Timbira. São Paulo : USP, 1982. (Disertação de Mestrado)

- --------; AZANHA, Gilberto. Os "Timbira atuais" e a disputa territorial. In: RICARDO, Carlos Alberto (Ed.). Povos Indígenas no Brasil : 1991/1995. São Paulo : Instituto Socioambiental, 1996. p. 637-41.

- NINUENDAJÚ, Curt. The Eastern Timbira. Berkeley : Univer. of California Press, 1946. 357 p. --------. A habitação dos Timbíra. In: SCHADEN, Egon. Leituras de etnologia brasileira. São Paulo : Companhia Editôra Nacional, 1976. p. 44-62.

- OLIVEIRA, Adalberto Luiz Rizzo de. Ramkokamekra-Canela : dominação e resistência de um povo Timbira no Centroeste Maranhense. Campinas : Unicamp, 2002. (Dissertação de Mestrado)

- QUEIROZ, Maria Isaura Pereira de. Organização social e mitologia entre os Timbira de Leste. Rev. do Instituto de Estudos Brasileiros, São Paulo : USP, n.9, p. 101-2, 1970.

- RIBEIRO, Francisco de Paula. Memórias sobre as nações gentias que presentemente habitam o continente do Maranhão. Rev. do Instituto Histórico e Geográfico Brasileiro, Rio de Janeiro : IHGB, v.3, p. 184-97; 297-322; 442-56, 1841.

- VAZ, Leopoldo Gil Dulcio. A corrida entre os índios Canela. In: SILVA, José Eduardo Fernandes de Souza e (Org.). Esporte com identidade cultural : coletânea. Brasília : Indesp, 1996. p. 106-11. (Esportes de Criação Nacional, 2)

- Mending vilay : the Canela indiansof Brazil. Dir.: Stephen Schecter; William Crocker. Vídeo cor, 49 min., 1999.

- CROCKER, William; WATANABE, Barbara. 2002 The Canela : a website. Washington : Smithsonian Instituition’s.