Apurinã

- Self-denomination

- Popukare

- Where they are How many

- AM, MT, RO 10228 (Siasi/Sesai, 2020)

- Linguistic family

- Aruak-maipure

Scattered over sites close to the banks of the Purus, the Apurinã possess a rich cosmological and ritual universe. Their history has been heavily affected by the violence of the two rubber cycles in the Amazon region. Today they are fighting for their rights. Some of their lands have still not been officially recognised and are constantly invaded by loggers.

Name and language

Some argue that Apurinã – or in its older form, Ipuriná – is a word from the Jamamadi language. The group’s self-identification is popũkare. Some old texts refer to the word kãkite as the self-identifier. Kãkite signifies “people” but, according to some Apurinã, kãkite simply means “people” in the sense of the human species (“I saw people”, just as “I saw monkeys” or “I saw jaguar”), rather than in the sense of an individual community or ethnic group.

The Apurinã language is a member of the Purus branch of the Maipure-Aruak family (Facundes, 1994). The nearest related language is that of the Manchineri, or Piro, who inhabit the upper Purus in Brazil and, in Peru, mainly the lower Urubamba valley. Some Apurinã argue that they can also understand a little of the Kaxarari language as the result, according to their mythology, of their joint departure from the sacred land.

Location and population

The Apurinã inhabit 27 Indigenous Lands, at differing stages of the official recognition process; twenty have been fully demarcated and registered, three have been declared to be for their sole use, and four are in the identification study phase. The total area of those Indigenous Lands fully demarcated is 1,819,502 hectares; of these two are shared with the Paumari of Lago Paricá and the Paumari of Lago Marahã and one with the Torá, in the TI of the same name.

The area inhabited by the Apurinã in the 19th century was the middle Purus – from the Sepatini or Paciá rivers to the Iaco. However the Apurinã are traditionally a migratory people and their territory extends nowadays from the lower Purus as far as Rondônia. There are Apurinã areas in the municipalities of Boca do Acre, Pauini, Lábrea, Tapauá, Manacapuru, Beruri, Manaquiri, Manicoré (in the Torá Indigenous land), all in the state of Amazonas, as well as Apurinã living in various Brazilian cities and a village within the Roosevelt Indigenous Land, belonging to the Cinta-Larga indians, to whom a number of Apurinã are married.

The first naturalists, travellers and missionaries who ascended the Purus in the second half of the 19th century reported that the Apurinã, although living some distance back from the river, would come to its banks to fish and collect turtles. As non-indians began arriving, many Apurinã retreated to the upper parts of tributary streams while others, working in the rubber estates, also lived in isolated locations.

The different environments of the Purus have greatly influenced the way of life of the Apurinã. The difference between “terra firme” and “vargem”, or areas free from and susceptible to flooding, is critical. Areas of more “central” occupation, in other words further upstream, are always terra firme. The areas along the main riverbank can be either terra firme or vargem given that the river does not always flood onto both banks.

There are four Apurinã communities in the municipality of Boca do Acre; three along the BR-317 road (the communities of Km 124 and Km 137, both within the BR-317 Indigenous Land, and the community of Km 45 in the Boca do Acre Indigenous Land) and the Camicuã community in the TI of the same name located close to the town of Boca do Acre.

According to Leôncio, head of the community of Km 124, the three communities now located alongside the road were founded by three survivors of a measles epidemic which wiped out the original maloca (communal residence) in the region. Leôncio’s mother, Kamapã, was one of the survivors and the current village of Km 124 is named after her. Maen, another survivor, gave her name to the village of her descendents at Km 137.

It is difficult to estimate the overall number of Apurinã, or even to consider them together, as they are so dispersed. According to Funasa (National Health Foundation), there were 4,057 individuals in November 2003. In 1996 in the Pauini region alone there were 1,114 inhabitants of the demarcated Terras Indígenas (UNI health report) and around 280 people in areas awaiting recognition (TIs Garaperi/Santa Vitória/Lago da Vitória/Capira, Baixo Seruini, Baixo Tumiã, Sãkoã/Santa Vitória and Mamoriá).

It also needs to be borne in mind that there are many references to Apurinã living outside the recognised indigenous lands, in towns along the Purus (Pauini, Lábrea, Tapauá) or in regional cities such as Rio Branco and Manaus. Many have migrated further afield, to Rondônia or even Rio de Janeiro and Minas Gerais.

History of contact

Systematic contacts between the Apurinã and non-indians started as a result of rubber collecting. The valley of the Purus began to be explored during the eighteenth century by itinerant traders in search of the so-called “drogas do sertão” (backland products): cocoa, copaiba balsam, turtle fat and rubber. Some of these explorers took up residence and processing plants began to be established on the lower Purus. In the 1850s and 1860s a number of expedition were sent to explore and map the river. According to the reports, by this time some Apurinã were already working for non-indians.

The Purus was occupied because of rubber. Exploitation started in the 1870s and by 1880 the Purus was occupied by non-indians throughout its length. Rubber collection declined after 1910 when Asian production, against which Brazilian production could not compete, began. With no market, the rubber estates were abandoned by the owners. The seringueiros (rubber tappers) and indians remained surviving through subsistence agriculture (which had been largely forbidden on the rubber estates) and marketing other products such as Brazil nuts.

Rubber enjoyed a new boom during the Second World War. The Allies needed rubber and the Asian plantations had fallen to the Axis. Fifty thousand north-easterners, called soldados da borracha (rubber troops), were shipped to the Amazon to work as seringueiros. The rubber estates were subsequently subsidised by the government; the removal of these subsidies provoked another collapse.

The Apurinã had differing types of contact with the rubber estates: whole groups were exterminated; some sold produce to the estates; others worked as seringueiros; some became involved right at the start; others had their first contact only during the period of the soldados da borracha. Apurinã stories tell of massacres, torture, the experience of slavery, of personal relations, of compadrio, of battles and wars over land. With the collapse of the rubber economy, no other substitute product achieved the same importance and no other system of production with similar weight was established in the region.

The SPI (Serviço de Proteção aos Índios) maintained a post on the Seruini river, a tributary of the Purus, in the present-day municipalities of Pauini and Lábrea. The Marienê post was founded in 1913, following conflicts in which around forty Apurinã and seven rubber tappers were killed, according to contemporary news reports. The high period of the post, an establishment with production objectives, occurred during the 1920s and the early 1930s. The post subsequently entered a period of decline and there were many accusations of corruption. At the beginning of the 1940s the post was closed down. Its location is the current Marienê village in the TI Seruini-Marienê.

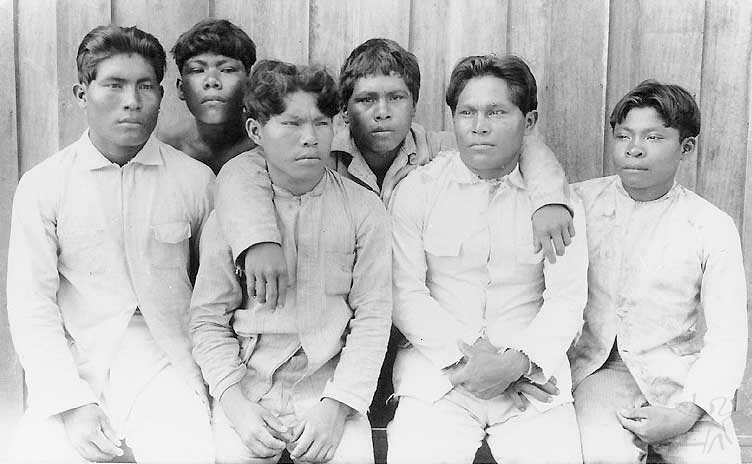

The Marienê post brought many Apurinã together in the same place. According to SPI ideology, its role was to bring the Apurinã to “civilization” and turn them into “useful workers” for the country. Nowadays the Posto Marienê is remembered by many Apurinã as a town where everything was organized, according to several informants. The negative side is also remembered: the corruption of the SPI agent, who retained the food supplies destined for the post and the clothes that the Apurinã were permitted to wear only when being photographed.

In the period 1977 to 1979, the Funai regional office in Acre carried out the first surveys of the Pauini region. At the end of the 1970s land conflicts were beginning, fuelling a reaction on the part of the indians to land occupations and exploitation. Along the Tacaquiri river in the Pauini region, the Apurinã residents led by João Lopes Brasil (known as Lopinho) opposed the municipality’s plans to open a road through their area. In the years that followed the conflicts grew and the prospect of the road continues to be shadow hanging over the residents of the TI Peneri-Tacaquiri. In 1995 a standoff (empate) led by Lopinho thwarted another attempt by the municipality to open the road. Implicitly or openly, the indians are considered by the non-indigenous residents as responsible for the “backwardness” of Pauini.

The Madeireira Nacional (Manasa) logging company is another source of conflict. Occupying an enormous area that covers part of the TI Tumiã, the mouth of the Seruini river and the TI Guajahã, the presence of this company and pressure it exerts led to the acceleration of the process of demarcating the TI Guajahã.

Another company able to exert pressure was Agro Pastoril Novo Horizonte or Zugmann. Located within the TI Seruini-Marienê, the company was involved in conflicts that led to the killing of José Lopes Apurinã and left a number wounded; some permanently. The firm later appealed against the demarcation although this did not prevent the full registration of the area, as the appeal was rejected.

The process of identification of the area was begun at a period when Apurinã political organization was still at its early stages. The Apurinã are currently demanding those areas which have not yet been recognized, areas where they live, areas they use along the banks of the Purus and its tributaries and even the headwaters, as in the case of Tumiã, which was left out of the area demarcated. The areas of natural grassland, important because this was where the Otsamaneru, the people who left the sacred land together with the Apurinã, had lived, were also only partially included within the limits of the area officially demarcated.

Social and political organization

One of the first things that an Apurinã from the Pauini region will explain about his people is that it is divided into two “nations”: Xoaporuneru and Metumanetu. Membership of one or other of these groups is determined by paternal lineage. Each of these “nations” has its own restrictions on what can and cannot be eaten: the Xoaporuneru are not allowed to eat certain types of tinamou (inambu relógio and inambu macucau), while the Metumanetu are not allowed to eat peccary. Breaking such dietary restrictions will cause health problems and even death, unless there is effective treatment by a shaman (“pajé” or “meẽtu”).

The proper form of marriage is between a Xoaporuneru and a Metumanetu, since marriage within the same “nation” is tantamount to marriage among siblings. In fact this is the term members of the same moiety use to address each other (nutaru, “brother”; nutaro, “sister”), just as Xoaporuneru and Metumanetu will occasionally address each other as nukero (“sister-in-law”) or nemunaparu (“brother-in-law”). An individual’s name indicates which of the “nations” he or she belongs to.

Among the Apurinã in the municipality of Pauini there are regional group names, which can be those of a river or of a kinship group. Thus those from the Peneri are known as Pedro Carlos’ people; those of the Seruini as Jacinto’s people; those of Água Preta as the Doctor’s people. What determines the denomination is always the name of the father. In the Apurinã language there is also identification by people: Kaikuruwakoru (people of the caiman), Yõpuruwakoru (people of the oriole), Wawakoru (people of the parrot), amongst many other examples.

However in the Boca do Acre region, the shaman and chief Leôncio gives other definitions, under which the Apurinã are divided into four sub-groups: Xoaporuneru, Metumanetu, Kowaruneru and Kaikuruwakoru.

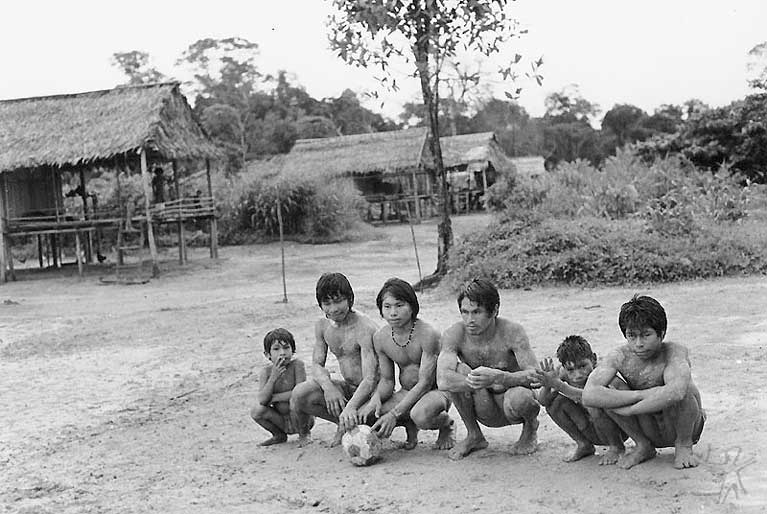

That which the Apurinã nowadays refer to as a “community” varies greatly. Sometimes a community is defined by the existence of a chief (cacique, liderança), a teacher or a health worker. Its spatial form can be very diverse and can include houses built around the same cleared space, a village, a dispersed set of dwellings (colocações), or even any combination of these. The historical evidence suggests that Apurinã dwellings have always been small.

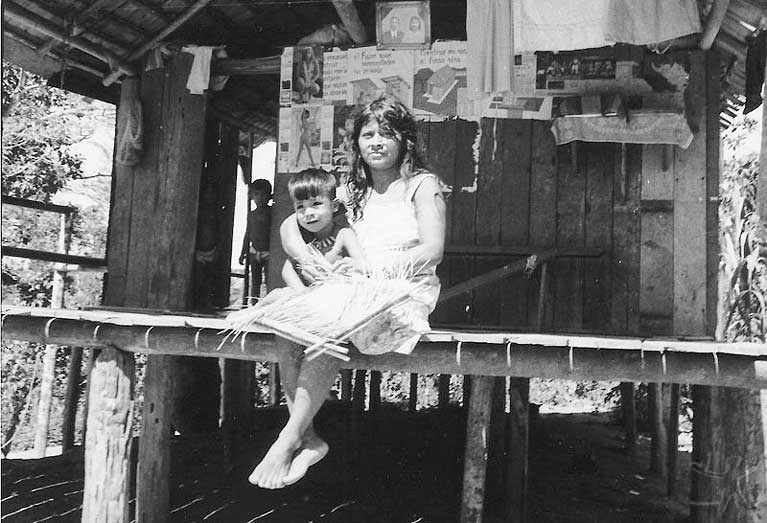

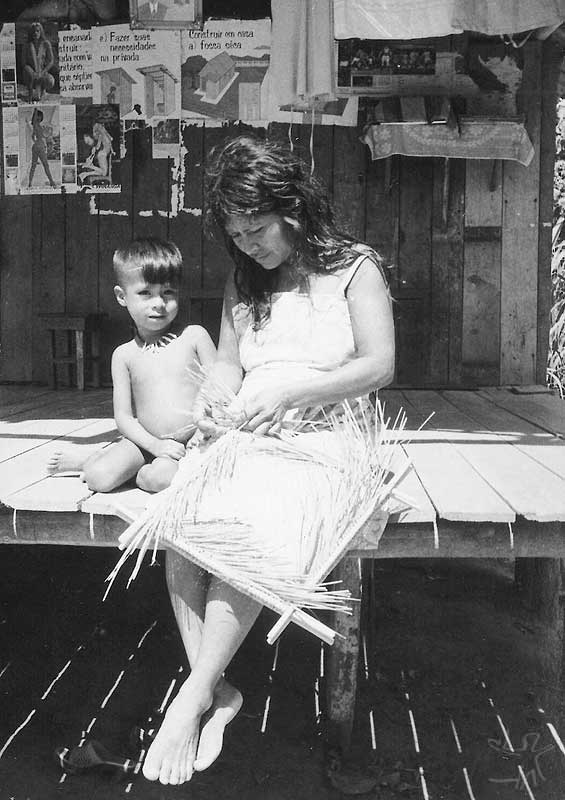

Nowadays the house (barraca, paraka or aiko) follows the same design as that of rubber tappers: tall and raised on wooden stilts embedded in the ground. Generally speaking each house is occupied by a single family.

In the “olden days” there were large dwellings, longhouses, malocas, aiko. Inside these, according to some early reports, families were separated by walls of palm leaf. According to the Apurinã, there was one entrance for men and another for women. Festivities took place within the house. Generally there is a patio (terreiro) and it is always a subject of comment when this is not kept clean. It is good to celebrate “Xingané” on a tidy patio. This cleared area round the house is often swept and the roots and stumps removed when there are celebrations.

A single dwelling can be that of a couple, with their sons, daughters, sons-in-law and daughters-in-law; as well as aged parents, parents’ siblings, in-laws, or single or widowed relatives. A village can also be comprised by the houses of several siblings who have remained together or even by the children of these.

Cosmology and mythology

Who is your God? I don’t know. I only know that his name is Tsora.

Artur Brasil Apurinã, Mũpuraru, Artur the Shaman, speaks thus about Tsora or, in his translation: God, Jesus. Tsora is the creator of all there is on Earth and for this reason is called God. The story of Tsora, the story of the beginning of the world, of the start of everything, always begins in its multiple versions with Mayoroparo, or “after the land caught fire”. Mayoru means vulture and Mayoroparo is a monstrous woman, a hag who devoured the bones of those who disobeyed (who have soft bones) and kept the bones of those who obeyed for manioc and potato cuttings at the beginning of the world.

Tsora is the son of Yakonero. Each night someone came to sleep with Yakonero. Wanting to know who the visitor was, she painted her hands with annatto and wiped them on his back. The following day it was the katokana (the shaman’s snuff pipe) that was seen to be black. Yakonero was thus banished. On the way to her parents’ house, her unborn son asked for various things. Annoyed, she beat her belly. To get his own back he gave her wrong directions to her house and she ended up at the house of the Katsamãũteru. The old woman who lived there hid her on a shelf and gave Yakonero – pregnant and thus wanting to spit – a gourd. She spat into this until it overflowed, thus alerting the men to her presence.

Yakonero bore four sons, on the branch of a cotton bush. Tsora was the smallest and weakest, but the smartest and most powerful. The brothers took their revenge by ambushing and killing, one by one, the killers of their mother.

The origin of everything that exists today can be explained by this story: the origin of the size of the Brazil nut tree, the origin of its sap, of the colour of the coati, the existence of several fish such as the surubim and the caparari, as well as the origin of revenge.

Tsora created people and the different types of people, the different peoples: Apurinã, whites, other indians. He administered several tests to these peoples and the Apurinã always did worse than other indians and than the whites. This is why, say the storytellers, that despite being “the best there is”, the Apurinã are few and divided amongst themselves.

Another extremely important story for explaining the Apurinã today is the Sacred Land and the Otsamaneru. The Apurinã were immortals and lived in a land where nothing got sick, went bad or died. They accompanied the Otsamaneru, travelling between one land of immortality and another. However they became overly enchanted with the things they found in the “mortal lands” lying between the sacred lands, and ended up staying in these.

The Kaxarari are frequently identified as the companions of the Apurinã on this journey. According to some accounts, the three peoples travelled together: Kaxarari, Apurinã and Otsamaneru. The Kaxarari were the first to become enchanted with the fruits of the “mortal lands”; then the Apurinã; whilst the Otsamaneru continued on their journey.

Ritual and shamanism

Apurinã ritual celebrations, generically known as Xingané (in Apurinã, kenuru) range from small nocturnal song sessions to large scale events involving invitations to several villages and offering substantial feasting, manioc wine, bananas, fruit of the patauá palm and fuel for participants’ boat travel. On some occasions these are rituals to pacify the souls of the dead, immediately after their decease or on the anniversaries. In such cases, according to Abdias, the ritual is known as isaĩ.

A Xingané begins with a ritual confrontation. The guests arrive from out of the forest armed, painted and decorated. They arrive shouting. The hosts, similarly armed, go to meet them. When they meet the leaders come forward and start arguing, speaking quickly and loudly (this dialogue is called “cutting sanguiré” in Portuguese and katxipuruãta in Apurinã), all the time with their weapons pointed at the others’ chests. Behind are the other members of the group, at the ready, and with their weapons similarly pointed at those involved in the argument. When the voices are lowered, so too are the weapons, and the leaders proceed to take snuff from each other’s hands.

At the start of the argument each declares not to know the other and asks who he is. There then follows the sanguiré, a personal speech that always closes with the confirmation of the speaker’s parents and grandparents. Camilo Manduca Apurinã summarizes it this way:

“When you cut sanguiré you have to recall the name of your father, mother, grandfather. What you wish to say, you have to say at the moment of the sanguiré. Whatever is going on, you have to find it out during the sanguiré”.

A ritual no longer practised, but still considered very important, is that of the Kamatxi. This celebration involves the presence of the Kamatxi, beings that live in the stands of buriti palms and who appear on the occasion of the ritual. Flutes are used and the women have to stay enclosed in a house, forbidden to watch.

Shamanism

The origins of illness and the shaman’s cure are stones. A stone is what enables the shaman to heal and what allows him to cause illness and death. Various reports state that during the initiation of a shaman, the first step is for him to remain for months in the forest, fasting or eating very little, and chewing katsowaru. Sexual relations also have to be avoided. When the shaman is given a stone, he inserts it into his body, as he will insert all the stones he receives or, in the future, extracts from the bodies of the sick.

A shaman heals by using katsoparu, a leaf that is chewed, and awire, snuff. The shaman has his own katsoparu and awire, but the person who asks for the cure is in general responsible for providing these for the occasion. The shaman should chew the katsoparu and take a lot of snuff. Sometimes the healing is carried out in private, in the sick person’s house; but often all are involved, talking and chewing, until the shaman starts the session. He heals by sucking the location of the illness. Often he will show the stone and explain the nature of the illness, how the patient acquired it and what he should do. He explains whether it the result of witchcraft or the action of an animal of the forest. He inserts the stone into his own body and can then recommend remedies and treatments. The remedies are in general plants, but they can also be manufactured medicines from the farmácia.

One of the most common problems shamans are called on to resolve is animals that pull, that carry away children’s souls. There is a set of foods that a father and mother must avoid when their child is still little; until the child is around two years old. The main prohibitions are large fish and game, but also beans, alcohol, coconut, pineapple, katsoparu, and mangoes. These last do not carry away the soul, but harm the health of the child since it will absorb the food through its mother’s milk.

During the night the spirit of the shaman will rescue the soul of the child. This is a dangerous exercise. If the shaman is weak he could, for example, become trapped at the entrance of a fish hole and die. The shaman arrives back with thunder and lightening and at his moment the child starts breathing again.

An Apurinã shaman works through dreams. In these his spirit leaves, visits other places and carries out tasks. Other spirits guide the shaman on these journeys: the animals and the chiefs of the animals (hãwite) with whom he works. Each shaman possesses one or more of his own: the jaguar, snake or mythical mapinguari.

Another common problem, both in children and adults, is being wounded by arrows fired by animal “bowmen” (kĩpuatitirã). These are the “chiefs” (hãwite). A new trail is especially dangerous. Children are bathed with the piprioca plant (kawaky) for protection or with breast milk. Those children with least resistance to the bowmen can die as a consequence of such attacks.

According to Otávio Avelino Chaves (Atokatxu), the chiefs of animal species are themselves shamans, or at least it is as such that they talk to human shamans. One of the roles of a shaman is to overcome and control these beings; for example, causing them to stop ‘haunting’ or snakes to stop biting. What others see as animals, the shaman sees as people and some as family. The shaman protects his community against enemy stones and prevents and cures attacks from animals of the forest.

If they are strong, shamans will travel to different lands – to beneath the land where they live, to below the river, even to the sky, where Tsora lives. The stronger the shaman, the more places his spirit is able to go to. If this is so in life, so is it also in death. Some say shamans never die, they become enchanted. Thunder is heard at the moment of a shaman’s death. When old shamans died they would give precise instructions about how they should be buried, so that they could later leave their graves. In some cases shamans’ graves stayed tidy. In other cases it is said that they could be found amongst herds of animals, such as peccary. The majority however go to the Sacred Land.

Material culture

The majority of the women make brooms (which are widely sold), as well as carrying and storage baskets. The open weave hammocks, nowadays rare, are woven from enviras (the inner bark of several different tree species).

Pottery artefacts are made from clay mixed with the powder resulting from burning the bark of the caripé tree. Used to prevent the pottery cracking, the bark is burned and then pounded with a mortar and pestle until it becomes a powder that is sieved and mixed in with the clay. The pottery is reddened with breu (the resin of the jatobá tree), which gives a shine to the object in a tone that varies from yellow to red. Sometimes designs are applied with water and salt after firing and before the application of the breu do jatobá.

Snuff boxes made of aruá (snail), sernambi (rubber residues) and small metal rings are also widely used. The katokana or mexikana, tubes for inhaling snuff, are made from animal bones.

Very characteristic of traditional Apurinã culture are the “barks” (aãta), canoes made from the bark of the jutaí tree. Nowadays these are mostly found among communities on upper stream. The jutaí bark is extremely light and offers the manoeuvrability needed on small streams. Their construction involves stripping the bark from the tree in the rainy season, opening it up by heating and inserting the cross-bench with another piece of wood.

Notes on sources

Among the sources of information on the Apurinã, Ehrenreich (1948 [1891]) is important as he describes the early years of contact. In addition there is much information in the reports of nineteenth and early twentieth century travellers and naturalists such as João Martins da Silva Coutinho (1862), William Chandless (1867) and Joseph Beal Steere (1903).

Cláudia Netto do Valle (1986) undertook linguistic research among the Apurinã of Km 45 that also included ethnographic observations. Sidney Facundes (1994) carried out further linguistic studies and proposed an alphabet for the Apurinã language.

Gunter Kroemer (1985) undertook an ethno-historical study of the indians of the Purus river. Marco Antonio Lazarin’s dissertation (1981) considers migration and population dispersal towards Manaus. Ethnographic information, including analysis of social structures, can be found in reports on the land question, such as that of João Dal Poz Neto (1985).

My master’s dissertation (Schiel, 1999) deals with the Posto Marienê of the SPI, drawing on documental sources. The ethno-ecological survey I carried out with Maira Smith for the PPTAL contains information on resource use and material culture, as well as considerations on economic projects and current problems.

My doctoral thesis (Schiel, 2004) is an investigation of the past, the memory and the history of the Apurinã using oral narrative, as well as ethnographic and documental data.

Sources of information

- CUNHA, E. da. “Rio abandonado, o Rio Purus”. Revista do Instituto Histórico e Geográfico Brasileiro. Rio de Janeiro, 68(2), 1907.

- EHRENREICH, Paul. “Viagem nos rios Amazonas e Purus”. Revista do Museu Paulista, vol. XVI: 279 – 312, 1929

- FACUNDES, Sidney da Silva. Morfemas "flutuantes" em Apurinã e a tipologia dos clíticos. Rev. Liames, Campinas : Unicamp, n. 2, p. 63-83, 2002.

- --------. Noun categorization in apurinã (Maipuran, Arawakan). Eugene. : Univ. of Oregon, 1994.

- -------. Hamo Ayõkatsopakataru Iye Popũkaruwakoru Sãkire (Vamos Escrever A Língua dos Apurinã). Belém : Museu Goeldi, 1966.

- -------. The language of the Apurinã people of Brazil (Maipura/Arawak). State University of New York at Buffalo: PhD thesis, 2000.

- FUNDAÇÃO DE CULTURA E COMUNICAÇÃO ELIAS MANSOUR; CIMI. Povos do Acre : história indígena da Amazônia Ocidental. Rio Branco : Cimi/FEM, 2002. 58 p.

- KOCH-GRÜMBERG, T. “Ein Beitrag zur Sprache der Ipuriná-Indianer”. In: Journal de la Societé de Americaniste, N.S., XI, 1919.

- KROEMER, Gunter. Cuxiuara: O Purus dos Indígenas. Ensaio etno-histórico e etnográfico sobre os índios do médio Purus. São Paulo : Edições Loyola. 1985.

- LAZARIN, M. A. A Descida do Rio Purus: uma experiência de contato interétnico. Brasília, 1981 (dissertação de mestrado).

- LIMA da SILVA, Raquel. Natureza, rainha da floresta e indianidade: o caso da igreja do Santo Daime entre os índios Apurinã da aldeia Camicuã. Monografia apresentada ao Departamento de Filosofia e Ciências Sociais, Universidade Federal do Acre, 2002.

- Luciene Cristina Risso 2005. PAISAGEM, CULTURA E DESENVOLVIMENTO SUSTENTÁVEL: Um estudo da Comunidade Indígena Apurinã na Amazônia Brasileira. Tese de Doutorado, Unesp.

- MAHER, Tereza Machado (Org.). Asãgire. Rio Branco : CPI-AC, 1993. 27 p.

- METRAUX, A. “Tribes of the Jurua-Purus Basins”. In Stewart (org.) Handbook of South American Indians, vol. 3, Nova York: Cooper Square Publishers, 1963.

- NIMUENDAJU, Kurt "Vocabularios Makusi, Wapicana, Ipurina e Kapisana”. Journal de la Societé des Americanistes, 44, Paris, 1955.

- NOGUEIRA, Ana Luiza Estellita Lins. Apurinã. In: GONÇALVES, Marco Antônio Teixeira (Org.). Acre : história e etnologia. Rio de Janeiro : Núcleo de Etnologia Indígena/UFRJ, 1991. p. 113-44.

- PEREIRA, Cláudia Netto do Vale. Ponpukare ou nós mesmos : uma investigação sobre o ritmo numa sociedade de tradição oral. Campinas : Unicamp, 1986. (Dissertação de Mestrado)

- POLAK, J.E.R. A grammar and Vocabulary of the Ipurina Language. London : Harrison & Sons, 1894.

- RIVET, P. & TASTEVIN, R. P. “Les langues du Purus, du Jurua e des régions limitrophes”. Anthropos, 14/15: 298-325; 16/17: 298-325, 819-28; 18/19: 104-13, 1919-24.

- -------. “Les Langues Arawak du Purus et du Jurua (groupe Arauá)”. Journal de la Societé de Americanistes, XXX-XXXII, 1938-40.

- SCHIEL, Juliana. Entre patrões e civilizadores : os Apurinã e a política indigenista no meio rio Purus na primeira metade do século XX. Campinas : Unicamp, 2000. (Dissertação de Mestrado)

- -------. Tronco Velho: histórias Apurinã. Unicamp, 2004 (tese de doutorado).

- ------- & SMITH, Maira. Levantamento Etno-Ecológico/Complexo Médio Purus I/Relatório Final. PPTAL/FUNAI: manuscrito, 2001.

- SCHRÖDER, Peter. Levantamento etnoecológico : experiências na região do Médio Purus. In: GRAMKOW, Márcia Maria (Org.). Demarcando terras indígenas II : experiências e desafios de um projeto de parceria. Brasília : Funai/PPTAL/GTZ, 2002. p. 223-39.

- SCHULTZ & CHIARA. “Informações sobre os índios do alto Purus”. In Revista do Museu Paulista, vol. IX: 181-121, 1955.