Anambé

- Self-denomination

- Where they are How many

- PA 182 (Siasi/Sesai, 2020)

- Linguistic family

- Tupi-Guarani

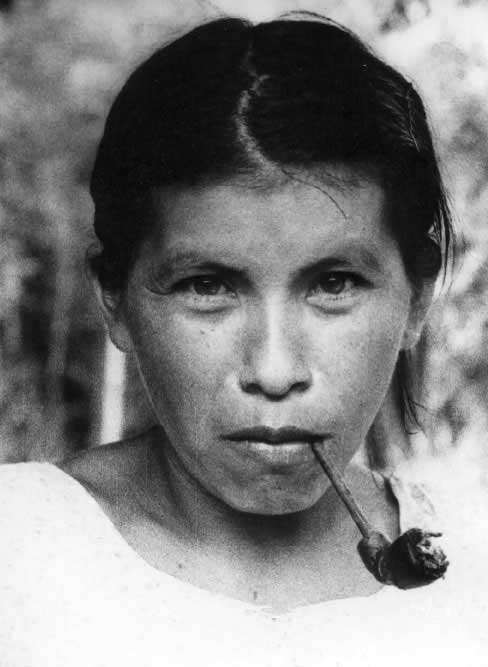

The Anambé live like the sertanejos (inhabitants of the sertão, the backlands) of the region. Their homes are the same as the local inhabitants’, and they buy merchandise in the local commerce. For some generations they have been intermarrying with non-Indians, integrating their partners and their children into village life. They react, however, to any attempt of transfering the group from the Cairari region.

Name and language

The Anambé language belongs to the Tupi-Guarani branch. In the 1980s, every Anambé older than 40-years old was a speaker of the Anambé tongue, and all those between 20 and 30-years old understood it, but used Portuguese correctly.

Population

In 1940 the Anambé numbered 60 individuals. But their population dwindled, due to the fact that many women married regionals and moved away and because of successive epidemics of measles. But from the mid-1960s on the Anambé population started to recover; besides, inter-ethnic marriages began to attract non-Indian spouses to the Indigenous Land.

Surveys carried out in 1983 and 1984 respectively by the Conselho Indigenista Missionário - Missionary Indigenist Council - (Cimi) and the Fundação Nacional do Índio - National Foundation for the Indian - (Funai), the official organ for Indian policy, differ, perhaps due to the great mobility of the population (for example, between April and December of 1982, 12 Anambé families, a total of 30 to 35 people, were transfered to the Alto Rio Guamá Indigenous Land and returned from there to their region of origin). According to the Cimi, there were then 61 people living in the Anambé Indigenous Land, between Indians and non-Indians, and 11 Indians scattered in the vicinity and in towns in the area.

For the Funai, however, there were 20 Anambé in the Indigenous Land (plus 12 non-Indians); in the vicinity there were 4 Anambé married with non-Indians, in addition to 8 members of their families - most probably children of those inter-ethnic unions -, which at the time were about to move into the Indigenous Land; there were also two Anambé women living in Mocajuba, plus the son of an Anambé woman, besides an Anambé man who worked for the Funai in Itaituba, and others scattered along the Cairari and Moju rivers. Neither of these surveys were conclusive about the actual number of Anambé. Data by Funai from 1996 give a total of 118 inhabitants of the Anambé Indigenous Land, without distinguishing Indians and non-Indians.

History of contact

In the past, the Anambé Indians lived West of the Tocantins River, on the headwaters of the Pacajá River, which empties into the Pará River (an arm of the estuary of the Amazon River that runs South of Marajó Island), near Portel. According to a narrative of an Anambé leader taken by researcher Fereira Pena in 1884, they had lived for a long time on the headwaters of the Pacajá, under the orders of a wise warior leader who came from the West.

The whites first came to wedge war against them; then the Jesuits, who were at peace with the Anambé, began to separate wives from husbands and take many of them to Portel, the men to work on the roças (planting fields) and to become oarsmen, the women to wash clothes and cook. That displeased the Anambé very much, leading them to disobbey the chief and to break up from the others. Cannibal Indians then came to make war against them, so they moved to the headwaters of the Cururuí River, a tributary of the Pacajá, where they formed the village of Tauá, from where later they moved to a place where the director of Indians tried to group them into a village manned by whites.

In 1852, in fact, part of the Anambé came to the left bank of the Tocantins, asked for protection and was placed in a village close to the district of Baião. The others remained on the upper Pacajá. By 1874, after a war against the Indians called "Curumbu", they had been reduced to 46 individuals; the following year, 37 of them died of smallpox. The survivors joined the Anambé who were living on the village by the Tocantins River. The Anambé thus started to live in the vicinity of the city of Baião, on the islands of Santos and Tauá. Until the end of the 19th Century, the Anambé moved back and forth from the Tocantins and the Pacajá, until they eventually crossed to the east bank of the Tocantins and into the basin of the Moju River.

The first records of the presence of the Anambé in the Moju River basin confuse them either with the Turiwara or with the Amanayé. According to what the Amambé told anthropologist Napoleão Figueiredo, upon entering the headwaters of the Moju they met the Gaviões do Oeste Indians, who expelled them, thus forcing them to move towards the Cairari. At first they were the only inhabitants of the upper Cairari, but as of mid-20th Century loggers and gatherers of balata started to come into the area. In the beginning the Anambé did not get involved in timber extraction, instead selling furs, meat of wild animals and flour. In the 1970s, a few Anambé worked as loggers on a daily basis, while others sold wood to a regatão (Amazon merchant who ply the region's rivers selling merchandise and buying local products), who generally worked for the same timber company. But the involvement of the Amambé with logging was intermittent then, and became only occasional in the following decade.

Way of life

The Anambé have lost the majority of their external Indigenous cultural elements, and their way of life is very similar to that of the local, non-Indian inhabitants. Covered with straw or woods chips, theirs are no different from other houses in the area. Except for small baskets, fans, spiral sifters, spindles, pilões (heavy mortars used for pounding corn and other grain), ubás (primitive dugout canoes), bows and arrows, all the equipment the Anambé use in their daily lives is bought. For some four generations there have been inter-ethnic marriages with regionals, with the non-Indian spouses and the offsprings of those unions integrating into life in the village. In the 1980s, an old leader, maybe the only one who still knew the old traditions and chants, held a prestigious position, but the leadership belonged to a younger man who was familiar with urban life, chosen because he was more at ease when dealing with the regionals.

The Anambé told Napoleão Figueiredo that in the 1940s they were taken to Belém and baptized; the godfather of them all was State governor Barata. Beginning in the 1960s, they started to take their children to be baptized in Mocajuba, town to which they go to celebrate its patron saint. The Anambé also have contact with the pentecostal from Vila Erlim, near their village. Their mythology has had both Catholic and Evangelical influences, and the figure of the pajé (shaman) has disappeared a long time ago.

The Anambé no longer sell copal oil and maçaranduba (cow tree) milk as they used to in the 1950s and 1960s. They only cut trees when they need money. They sell regularly the surpluses of their roças (maize, rice, manioc flour), and occasionally meat of wild animals, either to the regatões who visit the village or directly in Mocajuba. In addition to agriculture, other activities help in their subsistence: hunting, carried out in group by the men armed with shotguns, along with the capture of river turtles by women and children, exert extra pressure upon the local fauna, which is already threatened by deforestation by rural enterprises and timber companies; fishing, in which fish hooks, lines, bows and arrows are used, carried out especially in the dry season; and the gathering of fruits and honey.

Sources of information

- ARNAUD, Expedito C.; GALVÃO, Eduardo. Notícias sobre os índios Anambé (Rio Caiari, Pará). Boletim do MPEG: Antropologia, Belém : MPEG, n. 42, 17 p., set. 1969.

- CEDI. Anambé. In: RICARDO, Carlos Alberto. Povos Indígenas no Brasil. v. 8, Sudeste do Pará/Tocantins. São Paulo : Cedi, 1985. p. 150-61.

- FIGUEIREDO, Napoleão; SILVA, Anaíza Vergolino. Projeto Cairari : diário de campo. Belém : UFPA, 1969.

- --------. Projeto Cairari : fototeca. Belém : UFPA, 1969.

- GOMES, Jussara Vieira. Grupos indígenas Amanayé e Anambé do Pará : relatório. Boletim do Museu do Índio, Rio de Janeiro : Museu do Índio, n. 7, 72 p., dez. 1997.