Iranxe Manoki

- Self-denomination

- Manoki

- Where they are How many

- MT 413 (Siasi/Sesai, 2020)

- Linguistic family

- Iranxe

Manoki is the name by which the Indians who are more commonly known as Irantxe call themselves; their language bears no similarity with other language families. Their history, however, is not very different from most other Indians in Brazil: they were practically decimated as a result of massacres and diseases from their contact with the whites. In the mid-20th Century, most of the survivors saw no other alternative but to live in a Jesuit mission, which was responsible for the profound socio-cultural destructuration of the group. In 1968, the Manoki received land from the federal government outside the area of their historical occupation, and the environmental characteristics of which made their traditional use of resources unviable. The fate of the Myky, a Manoki group which remained isolated from the national society until 1971, differed little from that of the Manoki. Since then, they have suffered equally from the consequences of the landholding speculation which has affected the area surrounding their territory. Presently, both groups are making claims to increase their lands.

Location

The Manoki are located on two Indigenous Lands in the western part of the State of Mato Grosso, both lands being part of the municipality of Brasnorte: the Manoki Indigenous Land, in the region of the Cravari River, and the Myky Indigenous Land, on the banks of the Papagaio River. The first has six villages: Paredão, Recanto do Alípio, Perdiz, Asa Branca, Treze de Maio or Village of Maurício and the largest of all, Cravari.

Since its creation by a Presidential decree in 1968, when it was ratified with an area of 46,790 hectares, the limits of the Irantxe (Manoki) Indigenous Land have been questioned. In 1971, when news of the existence of an isolated group (see "the case of the Myky")were published, the Manoki took the decision to claim new limits for their lands which would include these "isolated" groups. With the support of the Jesuits, the territory was partially enlarged in 1977. But these new limits were only ratified in 1990 and, shortly afterwards, were disputed by the Indians. Finally, in 1991, they sought the help of the anthropologist Darci Luiz Pivetta in Cuiabá to re-examine their historical territory. It was confirmed that the location of the present Manoki Indigenous Land corresponds to an area of low forest traditionally occupied by the Pareci, ecologically quite distinct from the original habitat of the Manoki, which is the forested areas between the Cravari River and the Sangue River.

The region in which the Manoki Indigenous Land is inserted has come to be occupied since the 1980s by large agricultural enterprises specializing in mechanized agriculture (production of soybeans, rice, corn, and sugarcane, using great quantities of industrial and defensive agricultural fertilizers) and cattle-raising activities with between 50 to 100 thousand head of cattle. The result has been increasing deforestation, pollution of the water sources, impoverishment of the regional flora and fauna and restrictions on the movements of the Manoki outside their demarcated area. These predatory activities in the area surrounding the Indigenous Land has negative repercussions also on the area inside the Indigenous Land, which has become poorer yet in natural resources than the areas around it.

Approved by the Funai in 2002, the proposal for enlargement of the Manoki Indigenous Land corresponds to an area of 206,455 hectares, contiguous with the eastern side of the present demarcated area. These are lands which are better preserved and which include the headwaters of the 13 de Maio River, as well as the principal tributaries of the São Benedito River. In the past, this region was populated by numerous Manoki villages, and thus contains places known by the Indians and in which their ancestors are buried.

On the other hand, a good part of their historical territory (the right bank of the Cravari River up to the confluence with the Sangue River and the left bank of the 13 de Maio River) remained outside the delimited area, and is already quite changed by settlements and ranches, without even minimal environmental conditions for the physical and cultural subsistence of the Indians.

The Myky Indigenous Land - inhabited by this Manoki group who were contacted in 1971 - has a surface area of 50 thousand hectares. Demarcation was done in 1978 and it was ratified in 1987, excluding many areas which the Myky recognize as theirs. Consequently, the traditional use of the natural resources has become limited and soon they will also begin the process of enlargement of their lands.

History of occupation and contact

The historical territory of the Manoki people, according to their oral memory and historical records, covered the area between the left bank of the Sangue River and the right bank of the Cravari River, the Membeca stream to the south and the junction of the Cravari and Sangue rivers to the north. Marechal Rondon, in his "Lectures" (1910), refers to the Irantxe and locates their territory in this same area; as do other authors (mentioned in the item "note on the sources"). In his research in 1992, Pivetta, with the help of the older Manoki reconstructed a list of 27 old villages, estimating a population of more than a thousand people in the beginning of the 20th Century.

The following map situates the old locations of the Manoki villages as remembered by the older Indians, or that were recorded in the diaries of the Jesuits and in notes by the telegraph line expeditions of Rondon, as well as the trails that connected them and the natural resources that traditionally were most utilized.

The trails were the product of the visits that the Manoki made between villages, a result and condition of the relationships between the inhabitants of various locations within their territory; they were trails for hunting and fishing, for gathering food and materials for daily use in the villages. These trails were the evidence of the pattern of territorial occupation and use of its natural resources, and even served as guides for the penetration of rubber-gathering in their society, as the report of João Salustiano Lyra, referring to the exploration of the Cravari River valley in 1907, confirms:

"The primitive trails of the Indians, connecting the sources of the headwaters, whether in the same direction or in opposite directions, were the trails that guided the pioneers of civilization in these deserts and presently constitute real rubber-gathering trails" (p.8)... "We had penetrated up to that point sufficiently to the North, still being able to follow in this direction along the Indians' trails, which connect the various headwaters on the left bank of the Cavary River. It's true that the exploration of this river has until now been limited to its left bank, for the entire right bank is still occupied by the Irantxe Indians, who were always opposed to any invasion" (Public. N.7, annex 3, of the Rondon Commission).

According to reports of the older Indians, the direction the Manoki took in their movement was guided by nearness to the Membeca stream and the Sangue River going towards the 13 de Maio River. One of the alleged reasons for their migrations was the attacks of the Tapayuna and, in several cases, the Rikbaktsa. But the involvement of the Manoki with the national society is intimately connected to the process of regional occupation, deeply shaped by rubber-gathering expansion fronts, by the actions of the State and Jesuit presence.

The region north of the present State of Mato Grosso, outside the short-lived mining activities on the upper Arinos in the 18th Century (Arruda, 1992), was only affected again by expansion fronts during the rubber boom of the second half of the 19th Century. But, until the beginning of the 20th Century, nothing was known about the Manoki and their region was still practically untouched. But then, in 1907 government interest in defense of the national frontiers opened another penetration front with the construction of the telegraph line, the goal of which was to facilitate communication between Cuiabá, Santo Antonio do Madeira (present-day Porto Velho), Acre and Manaus and the rest of the country.

The Strategic Telegraph line from Mato Grosso to Amazonas, which was built under the direction of the then Coronel Cândido Mariano Rondon, in 1907 had already cut through the territory of the Pareci, beyond the city of Diamantino, following the rubber camps that were beginning to dot the region. The works of the telegraph line were accompanied in 1910 by the creation of the Indian Protection Service (or Serviço de Proteção aos Índios e Localização de Trabalhadores Nacionais (SPI). The objective of the SPI was to facilitate the attraction and pacification of hostile Indians, their gradual acculturation and integration into the national society through agricultural colonies, where they would be settled together with non-Indian peoples of the interior as manual laborers. It is in this regional context that the relations of the Manoki with the national society began.

The massacre on the Tapuru stream

The first encounter was tragic. It took place around the year 1900, when rubber-gatherers, led by Domingos Antonio Pinto, organized a massacre of the population of one of the Manoki villages on the Tapuru stream, tributary of the right bank of the Cravari River, as Rondon reported:

"There is nothing to fear from the peaceful and even timid disposition of the Iranche. But despite that, the cruel rubber-gatherer thought it was necessary to expel them from the area around the camp where it was established; and since there existed a village there, he agreed to surround it, with the help of his companions all of whom were armed with rifles. Before daybreak, on restarting the daily drudgery of that pitiful population, the criminal ambush opened fire, gunning down the first people to leave their houses. Those who escaped death, shut themselves up in their huts, in the vain hope of finding shelter there against the fury of their barbarous and unsolicited enemies. These however were already beside themselves at the sight of the blood of their first victims and nothing could stop them from satiating their hunger for massacre. Then, one of them, to better kill the pitiful escapees, decided to climb on top of one of the huts, open a hole in the roof and stick his rifle through it, aiming and shooting at the people who were there, one after another, independent of sex and age. So shocked by such abominable impiousness, the Indians finally found in the excess of their despair the inspiration to react in revolt: an arrow was shot, the first and only one to be shot in this whole bloody drama, but which pierced the glottis of this most cruel shooter, who fell lifeless to the ground. Just the memory of what then happened makes one tremble with indignation and shame. Where is there a soul of a Brazilian who doesn't vibrate together with ours, on knowing that that population, of men, women and children, died burnt, inside their huts which were put to fire" (Rondon, 1946:88-89).

Max Schmidt also makes reference to this cruel massacre (1942:35), which was told to him by the Indians on various occasions. The second recorded contact in history with the Manoki, this time peaceful, took place in 1909 (Rondon Mission, 1916), in the dry season, when a group of them was found walking under the telegraph line, in the area around the Utiariti station, on the right bank of the Papagaio River. They communicated with the Pareci employees of the telegraph line and asked them for tools. At the time, they refused to indicate the location of their houses.

However, in Manoki oral history the first peaceful encounter took place a little before the coming of this group to the telegraph line. Several years after the massacre at the village of Tapuru stream, a Manoki chief who had gone out hunting together with his son, on returning home found four White men in the empty village. The others had fled in fear. This chief received tools from these White men, which stimulated the others of the group to go after those White men until they got to an area near the telegraph station of Utiariti, in 1909.

From that time until 1932, Manoki groups became accustomed to sporadically visiting the Utiariti station, always looking for iron tools and never revealing the exact location of their villages. After 1932, they were not seen again.

Ironically, the telegraph line became obsolete just when it was finished, which coincided with the beginning of radiotelegraphy in 1922. Having been abandoned after the withdrawal of the Rondon Commission, this geographic and ideological space which had been created by the opening of the line came to be occupied by the Jesuits, whose presence was decisive in the process of intermediation between the indigenous peoples of the region and the national society and, especially, in the case of the Manoki.

Expansion fronts and missionary wardship

From the time of the foundation of the Diamantina Prelacy in 1930, with headquarters in the city of Diamantino, the Jesuits had already made incursions to the interior of the State for the purpose of evangelizing the indigenous and rural populations. In 1946, they established the Mission of Utiariti, on the left bank of the Papagaio River, with an area of 8,200 hectares granted to the Diamantina Prelacy by the state government. The Jesuits disputed the evangelization of the Indians with the missionaries of the ISAMU (Inland South American Missionary Union, which had been there since 1937) and with the employees of the SPI on the Tolosa Post, created in 1945 to implement the attraction of the Manoki.

Until then, the Jesuits met with little receptivity from the Indians and even from the employees of the telegraph line, which comprised most of the population of the surrounding areas. However, the phase inaugurated with the move to Utiariti made possible the consolidation and expansion of the Indian mission.

The success of the Missionary Post is directly related to the third rubber boom of Mato Grosso. The Second World War led to an increase in the demand for rubber on the international market, stimulating the migration of thousands of impoverished men from their homes, especially from the Northeast, who invaded the Amazon forest, from the north and the south, reaching places which had never before been explored, such as the equatorial forests of the Papagaio, Sacre, Sangue, Arinos, Juruena, Aripuanã, and Roosevelt river basins.

These expansion fronts which penetrated the territories of indigenous groups which before had only sporadically and marginally been reached provoked innumerable points of tension and armed conflict with the Indians. The genocidal skirmishes and spreading of lethal diseases, besides resulting in increasing depopulation among the Indians, exacerbated inter-tribal conflicts, including pre-existing ones, as the increasing invasions tended to dislocate groups to the territories of others.

The Manoki houses were then visited in succession by the ISAMU, the Jesuits and SPI employees, who sought to attract and settle them in their respective centers. To get an idea of the degree of competition among the religious missions, it is enough to mention that the Protestant missionaries established themselves around 500 meters away from the Jesuit center in Utiariti, where they founded a school and Church.

One of the consequences of this initial, disorderly and competitive contact was the spreading of epidemics in almost all the houses and even in Utiariti, which caused a large number of deaths. This situation lasted until 1957, when the ISAMU left the place and the SPI officially delegated the indigenous wardship to the Jesuits.

At the same time, the Utiariti Rubber Company, owned by a cattle-rancher of the region, intended to expand its activities to the Cavari River and its tributaries, where the Manoki villages were located. In 1950 this company made a garden near the village and the rubber-gatherers were accused of abusing the women and provoking conflicts. In 1952 the company shed was burnt, which gave rise to the name for the place as Burnt Shed.

In 1949, the Jesuits opened up a mission post among the Manoki, in the village of "Captain Acácio", near the Cravari River, relocating them, in ever greater numbers, principally the children, to Utiariti. The sicknesses of the "civilized" people continued to cause deaths and, in 1950 and 51, the Korean flu struck the village of Captain Acácio, causing the deaths of nearly all of its inhabitants. The survivors sought refuge in Utiariti.

In the following years, attacks by the Tapayuna and Rikbaktsa continued, as did the deaths by diseases. Progressively the survivors were brought to Utiariti and there they stayed, not returning again to their territory.

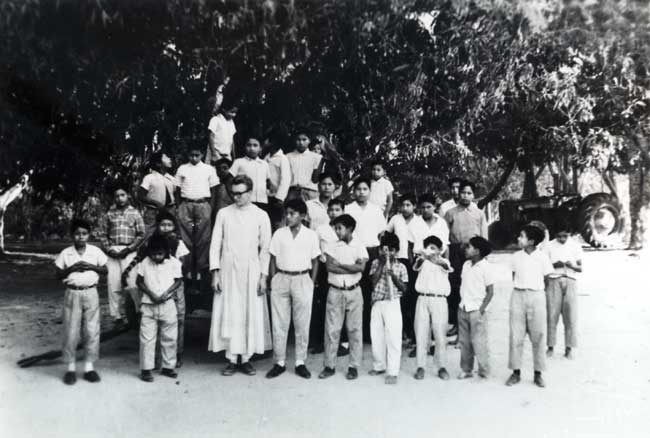

Under the command of the missionaries and through the intensive utilization of indigenous labor, the Mission buildings in Utiariti were enlarged and the Indians were broken up into groups of the same sex and age, supervised by a master (priest or nun, according to sex) in all of their activities. They were prohibited from speaking their own languages and inter-ethnic marriages among the Irantxe, Pareci and Nambikwara were encouraged. In the following years, this practice was extended to other peoples, with the pacification of the Kayabi of the river of the Fish in 1953, the Rikbaktsa of the Sangue, Juruena and Arinos rivers from 1956 to 1962.

Parallel to religious and technical instruction, the missionaries assumed the task of organizing indigenous labor according to the model of capitalist relations. Besides the plantations, there was a sawmill, a woodworking shop, mechanized sewing shops, artwork etc. The workers (men, women and children) who were most qualified, technically and in discipline, were promoted to the posts of chiefs and received salaries, acting as intermediaries in the planning and orders of the missionary or missionary in charge of the service. The reproduction of capitalist labor relations, which prepared the Indians for work in the regional labor market, included the control of the Mission in the commercialization of merchandise and usufruct of monetary results, which, even if they were re-invested in the boarding school, were done in the interests of sustaining and expanding the Mission. In 1956, with the aim of facilitating financial and contractual matters, the Prelacy created a civilian association with the name of the Anchieta Mission (MIA).

Until 1968, the Manoki stayed in Utiariti totally immersed in the civilizing conversion scheme of the Mission, except for several families who came to inhabit the village of José Parente and Maria Atolú, near the Cravari, in the same place where today there is the village of Asa Branca.

New Directions for the Missionaries and the Manoki

From the 60s on, regional occupation intensified, especially by cattle-ranching companies, miners, lumber, and colonization projects, made possible by the opening of roads, the principal one being BR 364, connecting Cuiabá to Porto Velho, which was finished in 1968. Conflicts with the indigenous population became frequent, resulting in the extermination of whole villages, a process which accelerated in the '70s and '80s.

The Mission could not remain aloof to these profound changes and in 1966 elaborated a new strategy, proposing the inclusion of lay missionaries (Brazilian and foreigners) in their work with the Indians. They went on to consider that, in order for the Mission to attain its objectives in the new regional context, there was a need for an effort to occupy strategic places for the penetration of the missions. They emphasized the search for and consolidation of contacts and accords with government agencies, labor syndicates, cooperatives and development associations. A gradual de-construction of Utiariti was initiated.

In the same year, an accord between the Anchieta Mission and the Funai put the head of the Mission, Father Edgar Schmidt, in charge of the Delegacy of the Funai in the region, with powers to define and interdict areas for the Indians under his guardianship. Based on the proposals of the MIA, indigenous reserves for the Irantxe, Rikbaktsa and Apiaká-Kayabi were created. Gradually the Indians who were still dispersed in their traditional territory and the "students" of the boarding-school were transferred to these reserves.

These historical changes set off within the Catholic Church a critical review of its historical role and produced a theoretical reflection allied with the Theology of Liberation. In the field of indigenist action, these influences were turned into concrete action with the creation of "Operation Anchieta" (OPAN), founded on February 6, 1969, during the 4th State Meeting of the Marian Directors of the State of Santa Catarina, through the incentive of Father Egídio Schwade, missionary of the MIA.

In the case of the Irantxe, an area outside that of their historical occupation was delimited by Presidential decree in 1968, on the left bank up to the mouth of the Cravari River, with a total area of 46,790 hectares (later ratified with 45,555 hectares) in a region of scrub forest, which was a different environment from that of their traditional way of life. According to the testimony of several Manoki, they didn't have a full understanding of the significance of the demarcation of the area. The priests knew where their traditional territory was, but the Tapayuna were still there and the Manoki were afraid to go back. Besides that, the missionaries did not discuss the matter completely with the group, for only the "captain" was consulted and he only indicated the territory where his village was established. The others accepted going there but, as they say, "at that time, it was all empty, there were no ranchers, there was no highway, there was nothing, we didn't know that it would all be occupied". They hadn't understood that, with that, they were losing their historical territory, where they still would roam and exploit its resources.

While a large part of the Manoki was in Utiariti, two Manoki villages maintained a certain autonomy: that of José Parente, where today there is the village of Asa Branca, and the village of Acácio, reoccupied by several Manoki years after the occurrence of the flu epidemics that decimated almost all its inhabitants. The village of Asa Branca was located outside the historical territory, although its inhabitants continued to wander through this territory to gather, hunt and fish. In the case of the village of Acácio, they avoided establishing settlements and gardens more within their traditional territory in fear of the attacks by the Tapayuna and the Rikbaktsa.

As soon as the Utiariti boarding-school was de-activated, all the Manoki left and went to the village of Asa Branca, of captain José, where the Jesuits set up a school, a pharmacy, a church and where the Sisters of the Immaculate Conception began to work.

In 1970, the Membeca cattle ranch set itself up in the region and began to cut through the Manoki reservation with a road, which was blocked by the FUNAI. This was the first step to a gradual surrounding of the Manoki, who, up to the 1980s still hunted, fished, and gathered outside the demarcated area, thus continuing to occupy their historical territory. Since then, the region has come to be ever more occupied by monoculture land-holders or cattle-raisers.

The case of the Myky

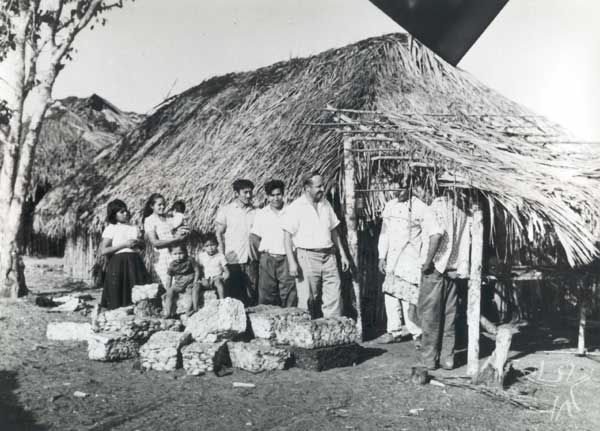

According to the report of Father Tomas de Aquino Lisboa (1979), in flying over the region, members of the Anchieta Mission in 1969 located two villages on the headwaters of the Rico stream, tributary of the Juruema River, indicating the possible existence of "isolated" Irantxe. An initial expedition by land was made by priests and Indians of the village of the Cravari River. But the village was found empty. In the following year, they made another expedition, which likewise failed.

In 1971 another flight over the area was made and another village was located, by a stream 20 kilometers from the old village which was named Hidden because it was in large part covered by the forest. Finally, a new expedition by land by the missionaries and two Manoki - Tapurá and Tupxi - made possible the first encounter with the group, comprised of about 23 people, who identified themselves as Myky (or Mükü, following the spelling of the priest Tomas de Aquino Lisboa, who was present on the occasion) and spoke the same language as the Irantxe.

The encounter was friendly and the visitors were received with roasted yams. The Manoki of the Cravari and the Myky struck up a lively conversation and performed the ritual weeping to celebrate their encounter. The group had been separated from the other Manoki in the beginning of the 20th Century, when they took to flight from the Whites after the massacre of the village of Tapuru stream. Since then, various visits were made with exchanges of presents. They took axes, sickles, hooks and knives, receiving from the Myky foods such as corn beverage, peanut and manioc cakes, as well as nasal decorations and other adornments. One of the Myky girls was offered as a wife to Tapurá, who declared himself widow.

On the second visit, the visitors stayed the night in the village and were shown the sacred flutes yetá (or jetá), prohibited to the women. Tapurá decided to marry and live definitively in the village. Father Tomas de A. Lisboa then took 12 Manoki to the marriage festival of Tapurá (see the item "Rituals"). Since then, the relations between the Manoki of the Cravari and the Myky have been frequent, with various marriages among members of the two groups. The Myky represent a strong cultural reference for the other Manoki, for they still abide by the traditions of the ancestors and practice certain rituals, such as initiation, which had been abandoned.

In 1973, the Anchieta Mission alerted the Funai of the danger of the penetration fronts, which were rapidly getting closer to the Myky area, in which demarcation and cutting of the forest had been done at less than five kilometers from the village. After that, the area was invaded and the demarcation marks destroyed. In 1974, 35 thousand hectares were interdicted by Presidential decree. In 1978 the area was demarcated with a total of 47,094 hectares.

Father Tomas de A. Lisboa went on to live among the Myky in 1976, and, at the end of 1979, Elizabeth Rondon Amarante, nun of the Congregation of the Sacred Heart of Jesus, also went to live among these Indians, who at the time were already confronting land problems, for they were surrounded by ranches, as well as demographic problems, since there were only four families and, due to their kinship system, there were limited possibilities for marriage.

Population and villages

Pivetta, in 1992, reconstituted with the help of the older Manoki a list of 27 old villages, estimating a population of more than a thousand people in the beginning of the 20th Century. When the Manoki villages were located for the first time, in 1947, the population was calculated at 258 people, thus representing a reduced number of survivors from the massacres, epidemics and attacks by the Tapayuna and Rikbaktsa. Father João Dornstaudter presented the following demographic census: "in 1948: 90; May, 1951: 70; October, 1952: 55; May, 1953: 59; August, 1953: 54; March, 1956: 54" (Cited by Moura and Silva & Pereira, 1975: 23).

When they were living in Utiariti, there were numerous marriages with people from other ethnic groups under the guardianship of the Mission: the Pareci, Nambiquara and, a little later, with the Kayabi and Rikbaktsa. Even so, the population continued to decrease in number: in 1965 there were 52 and in 1974, 50. From then on, the population resumed its growth but by then in a social environment which was deeply changed by the Jesuit presence and by the large number of marriages with people from other ethnic groups, which meant imposing the use of the Portuguese language as a means of communication. It also forced them to abandon many of their customs due to the lack of an environment in which these could be maintained.

The data from the Mission indicate that in 1979, a total of 136 people were already inhabiting the Irantxe reserve, and in 1982, there were 142. In 1983 (Arruda, 1983) there were 145 individuals, in 11 families of which both spouses were Manoki and in 17 families with one of the spouses belonging to another ethnic group.

According to a document of the Funai in 1987, there were 191 people and three villages. Finally, in the year 2000, according to the data of the OPAN, the Manoki had a population of around 250 people, distributed in six villages: Paredão (60), Recanto do Alípio (12), Perdiz (26), Asa Branca (24), Cravari (119) and Treze de Maio or the Village of Maurício (9).

<col width="114"/> <col width="61"/> <col width="56"/> <col width="52"/>

|

Age |

Gender |

Total (2000) |

|

|

0 - 11 months |

Masc. |

Fem. |

10 |

|

04 |

06 |

||

|

01-05 |

15 |

26 |

41 |

|

06-15 |

31 |

34 |

65 |

|

16-25 |

25 |

23 |

48 |

|

26- 50 |

28 |

23 |

51 |

|

51-60 |

04 |

05 |

9 |

|

60+ |

08 |

04 |

12 |

|

absent |

07 |

07 |

14 |

|

TOTAL |

122 |

107 |

250 |

There is also one Manoki family living outside the village, on the Dondico ranch, since 1998, besides others living in other indigenous areas of the region.

The largest concentration of inhabitants occurs in the village of Cravari, to the side of the São Domingos stream, around two kilometers from its crossing with the Cravari River. In this village there is a soccer field, church, school, infirmary and barracks to keep the truck. In the village of Paredão, the closest to the highway, there is the house of the head of the FUNAI post which is supplied by electricity.

Several houses are made of wood, others of mudwalls, with buriti thatch covering, boards or compressed fiber. Generally there are three rooms, one of them being a kitchen. In 2000, with the support of the OPAN, they built a longhouse in the traditional style, with a buriti thatch covering which extends to the ground, thus also forming the walls, situated in the middle of the village of Cravari. Outside the village, in a place hidden by the vegetation, there is the house of flutes called Yetá, which is only used by the men, and is prohibited to the women and children.

The villages have no fixed form, but the houses are built at a certain distance from each other, in such a way that the dwellers are accustomed to cultivating certain plant species around their houses. All the villages are located near streams and make use of the forest bordering these streams - only in these places is there found some natural fertility - for their gardens.

As for the Myky, since contact, they have never suffered population loss. They were 23 individuals in 1972; 28 in 1982; 33 in 1983; 31 in 1986; in 1997 they were 67. Today there are 76 people.

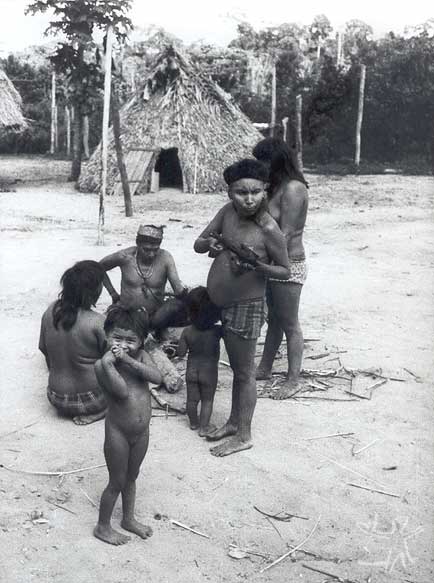

According to Father Tomas de Aquino Lisboa (1983), at the time of contact, the Myky longhouses were made of inajá thatch, with doors at the extremities and no internal divisions. Each nuclear family has its own space delimited by hammocks, gourds, pots, and food baskets, as well as by the suspended platform where meat or smoked fish was kept and the circles of manioc bread. In the straw of the hammock, arrows, knives and other objects were kept. A decade after contact, the longhouses were made in wood and covered by inajá thatch.

Economy and society

The enormous population loss, the expulsion from their own territory, evangelization and the historical process of involvement with the Brazilian society imposed severe restrictions on the reproduction of the Manoki way of life. Traditionally, these Indians' unit of production and consumption is the extended matrilocal family, with male labor being based on the cooperation between in-marrying husbands and their wives' fathers. But today there are also many young couples who make their houses separately, constituting elementary families as units of production and consumption, although they seem to maintain - even though in attenuated form - the obligations of cooperation and sharing characteristics of the relations of in-marrying husbands with their wives' fathers.

Each family is accustomed to making its garden near the village, from a half to two hectares in size, and cultivating bitter manioc, soft corn, sweet potato, yam, potatoes, rib bean, broad bean, arrowroot, urucum, cotton, peanut, and other species. Later they incorporated sweet manioc, sugarcane, hard corn, rice and pigeon pea.

According to the survey done in 2000 by the OPAN, it is calculated that the total amount of lands used by the traditional gardening system on the Manoki Indigenous Land does not surpass 500 hectares, comprised exclusively by forest bordering the streams, which has more fertile soil. However, from 70 to 80% of the soil of the indigenous land presents high acidity and low fertility. In the other 20 to 30 % of the area, the soils are poorer still and inadequate for the type of traditional planting that the Manoki do.

The production of corn, one of their most important traditional cultigens, is negligible due to the deficiencies in the soil. For the seeds not to be lost and to produce at least a little, it is necessary to fertilize the earth and, even so, they are barely able to produce anything in the traditional gardens. Mechanized planting has for several years been tried, but without much positive results, since it requires heavy costs in terms of soil correction, fertilizers and machinery. The traditional and more diversified gardens are being abandoned in favor of monoculture of rice, with poor results on the market, and resulting in the loss of variety, quantity and dietary quality.

Hunting, fishing and gathering have also produced ever poorer results due to the increase in the human occupation of the region and the characteristics of the model of occupation centered on the cutting of the forest covering for monoculture or pastures and on the intensive use of agro-toxins. Rheas, siriemas and partridges have diminished drastically. The gathering of forest fruits (for example, the pequi), is still practiced, principally by the women and children.

The traditional gardens continue to be made, sometimes (ever less often) accompanied by traditional rituals. However, there is an increasing migration of the younger men out of the village to work on ranches in the surrounding area, resulting in a re-organization of the traditional pattern of the division of labor and the composition of production units. Under these circumstances, the gradual and forced abandonment of their agricultural practices also means the impossibility of transmitting these practices, as well as the rituals and associated knowledge, to the new generations.

Besides working on the ranches, other sources of income are artwork (headdresses, cotton or tucum fiber hammocks, collars, etc.). bought by the Funai or sold by the Indians in their visits to the cities, and the sale of a small production of manioc flour and honey, in a Project that is assessed by the OPAN. But, according to the survey made by the OPAN in 2000, most of the money that circulates in the villages comes from retirement pensions (there were 13 people receiving a minimum salary) and the salaries of the teachers (4 indigenous teachers in the group of villages) and health agents (7 indigenous agents in the group of villages).

Traditionally, the Indians say, the post of chief passed from father to son. The older Indians remember several great chiefs of the past and their successors. As today, there didn't exist a general chief, only the village chiefs. On the Manoki Indigenous Land, presently the chiefs are elected by vote, there being no defined period of mandate. Their attributes include representing the community in external meetings, presenting community demands to the Funai, organizing community undertakings and summoning the others to participate. Despite being elected by vote, the present chief maintains the central characteristics of the traditional chiefs, in which the chief does not order but persuades. By the same token, he represents the community but cannot make individual decisions. Every important decision is taken through long processes of collective discussion until a consensus is reached.

The Manoki are assisted by the National Indian Foundation, in the jurisdiction of Tangará da Serra, which has a head of post in the area, and by the Anchieta Operation (OPAN), which maintains an indigenist there. Besides that, the Manoki receive health assistance with resources from the accord signed between the National Health Foundation (FUNASA) and the OPAN. The community is assisted by a team comprised of hired nurses and by indigenous health agents who provide basic assistance in the villages. More serious cases are sent to Tangará da Serra. These agencies develop social projects that also bring in resources for the community, generally set aside for purchasing machines and equipment and the implementation of small projects.

According to Tomas de Aquino Lisboa (1983), among the Myky, agriculture is based on manioc and corn, but they also plant a lot of beans, sweet potato, yams and peanuts. Since 1973, Tapurá (a Manoki man from the village of the Cravari who married and went to live among the Myky) introduced sugar-cane, which then came to be widely used, including in all fermented beverages which are made with boiled sugarcane and mixed with corn or sweet potato.

According to his 1983 report, each family then had gardens of corn, bitter manioc and beans. But at harvest time, it was common to share the products of the earth. Manioc is brought by groups of at least two women in large recipients balanced on the head by an embira. The manioc is then scraped and squeezed through a sifter (or twisted in a piece of cloth). The circles of manioc mass are placed on the ground to dry, and then kept on the suspended platforms (jiraus). The manioc bread is roasted in the ashes or in a frying pan and eaten with game, fish, beans, and peanuts. With the poison from the wild manioc, they make a highly appreciated drink.

According to the testimony of the Diário de Cuiabá in 1997, Elisabeth Rondon Amarante, nun of the Congregation of the Sacred Heart of Jesus who has lived among the Myky since 1979, fishing and hunting are scarce, due to the limited extent of the territory and predatory activities around it. Thus, the group has faced difficulties in finding ways to sustain themselves, like the Indians of the Manoki Indigenous Land.

Rituals

The traditional economic activities are intrinsically connected to ritual activities, such as the festivals of the dry season and those of the rainy season, each lasting approximately a month.

The oldest Indians remember that when they lived in their traditional territory, besides the family gardens, there were special gardens which were made for the initiation rituals, associated with the sacred flutes (the male initiation rites are called Yetá and the female rituals Nadipu) used exclusively by the men. Even today, they play them during the day in the house of the flutes - which is located outside the village and is hidden by the vegetation - and at night on the village plaza. It is prohibited for women and children to see them, and they should avoid even making mention of their existence. They say that if this interdiction is broken, the woman ends up being killed by the power of the flutes. The beliefs and rites associated with these flutes are at the center of their religion and their world view.

At the time of their initiation, the boys from 12 to 14 years old are separated from the other inhabitants of the village, spending weeks in the house of the flutes learning the secrets of the men and teachings which they will use in their adult lives. They should take this seriously, not in a playful way, they should be respectful and observe food restrictions. At the time of the cutting of the gardens (in the dry season), they would offer a garden to a woman, telling her that it was the flutes that made the garden. And all the men would help the initiates in the cutting and planting, playing the flutes at night. When the garden was ready, they would offer it to the chosen woman, who then would be responsible for taking care of it. The boys would then go back to the village painted and decorated, as men. When the garden eventually produced, the woman called the other women to distribute the food among all the families. The last festival of initiation on the Manoki Indigenous Land took place around 1995, according to information from the Indians.

The Myky, however, still perform these rituals. According to the version gathered by Father Adalberto Pereira (Cf. Lisboa, 1983) among this group, there are various types of rituals which go by the name of yetá. Each yetá is attributed to a person or family. On the nights of the ritual, the women and children remain inside the house, closed up, while the men outside hang up their hammocks and spend the night there, many of them playing their yetá and keeping rhythm with rattles containing pequi seeds tied on the right ankle. Inside the house, the women prepare the ritual drink.

Father Tomas de Aquino Lisboa was present at the marriage of the Manoki Tapurá with a Myky woman a few months after contact between the groups. The ceremony included the fundamental participation of the yetá flutes. As soon as they arrived in the Myky village, Tapurá and the other 12 Manoki of the Cravari went onto the Plaza forming two lines and playing their yetá. The Myky women and children were closed up in the ini ("house"). Visitors and guests made lively speeches, danced and played their flutes. Inside the house, the women pounded the corn to make chicha (fermented beverage). Later, the players entered the forest and put the flutes away in the sacred house. Then the women and children could leave the house, bringing the corn beverage and roasted potatoes.

The father of the bride wept, leaning on his bow and arrows, facing Tapurá. The girl approached both of them and then it was Tapurá's turn to do the ritual weeping. Later, inside the house, the mother of the bride weeps followed again by Tapurá's ritual weeping, this time inside the house. The other men go to the house of the flutes and come back playing them on the village plaza. The visitors are the first to play and dance and are observed with curiosity by the Myky, who were not familiar with the shaking of the wrattle tied to the ankle. The dances and songs are interspersed with speeches. Later, they play the flutes in front of each one of the houses and the women of each house thank them from inside.

The men return to the house of the flutes and the women weep in the house where Tapurá is with his wife. There are further dance sessions and speeches, which only come to an end at daybreak (Cf. Lisboa, 1979: 41-44).

In the rainy seasons, there were the festivals of the jacuri flute (or jakuy), not prohibited for the women to see and made with five tubes of taquara reeds of different sizes, placed and tied together in a sequence from larger to smaller. The women also participated in these rituals and played music referring to animals (armadillo, small armadillo, cará fish, skunk and all the others). The chief sponsor of the festival and his kin hunted and fished, while the women scraped manioc and made much bread. In these festivals, in general each man danced with a woman other than his own. Every night they danced almost until dawn and they slept very little. During the day, while the men left early to get honey and to hunt, the women stayed at home making manioc bread, for all to eat and then to continue with the festival. According to Lisboa, in 1983, among the Myky only the rituals with the yetá lasted throughout the night, while the festivals of jakui only happened sporadically and in the early hours of the night.

Lisboa comments that the Myky women used tucum fiber belts, the men used tucum wristbands and both sexes used earrings of sawgrass seeds. At the time of initiation, the nasal septum of the young man was perforated and, in the festivals, the xireti, or nasal flower, made of toucan feathers, was inserted in the hole. Body painting was quite simple and done with urucum. The men used headdresses made with bands of taquarinha (a species of straw) which they call xunã. The hair was cut in long bands a bit above the ears.

At the present time, the maintenance of their own religion has not prevented them from also following several aspects of Catholicism. In the village of the Cravari there is a church and they are accustomed to performing collective prayers on Sundays. They receive occasional visits from a priest to celebrate mass and perform baptisms. They also establish relations of fictive kinship, sometimes with FUNAI employees or non-Indian friends of the region.

Note on the sources

With regard to the history of occupation of the territory by the Manoki, Marechal Rondon, in his "Lectures"(1910), refers to the Irantxe and locates their territory; as do Roquette-Pinto (1935); Max Schmidt (1928, 1942), Pe. João Dornstaudter; Moura (1960:5); Pereira and Moura e Silva (1975:13); Pereira (1965:105); Métraux, (1942:161). Pivetta (1993), in his research in 1992, with the help of the older Manoki reconstructed a list of 27 ancient villages located between the Cravari River and the Sangue River, in the basins of the 13 de Maio, São Benedito and Membeca streams, (southern limit of their historical territory), estimating a population of more than a thousand people in the beginning of the 29th Century.

The history of the first contacts of the Myky with missionaries and the Manoki Indians of the village of the Cravari has been told by Father Tomas de Aquino Lisboa, who was present in these encounters and later an inhabitant of the village, in the book Among the Münkü Indians - the Resistance of a People, published in 1979. Another important document on the Myky was written by the same author eleven years after the first contact, but was never published, although the document can be found in the archives of the Socio-environmental Institute.

More recent information can be found in the publication Indigenous Peoples in Brazil 1996-2000, published by the ISA, which has short articles and news on the groups of the Manoki and the Myky Indigenous Lands.

Sources of information

- ARRUDA, Rinaldo S. V. Relatório circunstanciado de identificação e delimitação da Terra Indígena Manoki (Irantxe). Brasília : Funai, 2001. 45 p.

. Relatório de avaliação da situação Iranche. Relatório Fipe/Minter/Sudeco, v.2, n.3, p. 81-108, 1983.

. Os Rikbaktsa : mudança e tradição. São Paulo : PUC-SP, 1992. (Tese de Doutorado)

- CABIXI, Daniel Matenho. Educação escolar entre os Pareci, Nambikwara e Irantxe no contexto socioeconomico da Chapada dos Parecis - MT. In: VEIGA, Juracilda; SALANOVA, Andres, orgs. Questões de educação escolar indígena : da formação do professor ao projeto de escola. Brasília : Funai ; Campinas : ALB, 2001. p.57-72.

- CASTELNAU, Francis. Expedição às regiões centrais da América do Sul. Rio de Janeiro : Editora Nacional, 1949. (Brasiliana, 266).

- CHANDLESS, W. Notes on the River Arinos, Juruena, and Tapajós. The Journal of the Royal Geographic Society, Londres : Royal Geographic Society, n. 32, p. 268-80, 1862.

- CORREA FILHO, Virgílio. História do Mato Grosso. Rio de Janeiro : Instituto Nacional do Livro, 1969.

- DORNSTAUDTER, João E. (Pe.). Relatório testemunho do Pe. João Evangelista Dornstaudter. Cuiabá : Opan, 1976. (Mimeo).

- LENHARO, Alcir. Colonização e trabalho no Brasil : Amazônia, Nordeste e Centro-Oeste. Campinas : Unicamp, 1986.

- LISBOA, Thomáz de Aquino. Entre os índios Munku : a resistência de um povo. São Paulo : Loyola, 1979. 84 p.

- LISBOA, Thomáz de Aquino. Informações sobre os Myky. Diamantino : s.ed., 1983.

- LYRA, João Salustiano. Variante da Ponte de Pedra ao salto Utiariti e Aldeia Queimada. Publicação n. 7, Anexo n. 3 da Comissão de Linhas Telegraphicas Estratégicas de Mato Grosso ao Amazonas. Rio de Janeiro : Papelaria Luiz Machado.

- MELLO, Alonso Silveira de, (Dom). Missão do Mangabal do Juruena. São Leopoldo : Instituto Anchietano de Pesquisas, 1975. (Pesquisas, História, 18)

- METRAUX, A. The native tribes of Western Bolívia and Western Mato Grosso. Bulletin, Washington : Smithsonian Institute, n.134, 1942.

- MISSÃO Rondon : Apontamentos sobre os trabalhos realizados pela Comissão de Linhas Telegraphicas Estratégicas de Matto-Grosso ao Amazonas sob a direção do coronel de engenharia Cândido Mariano da Silva Rondon, de 1907 a 1915. Rio de Janeiro : Jornal do Commercio, 1916. 462 p.

- MOURA E SILVA, José de (Pe.). Fundação da Missão de Diamantino. Porto Alegre : Instituto Anchietano de Pesquisas,1975. (Pesquisas, História, 18)

. Os Irantxe : contribuição para o estudo etnológico da tribo. Porto Alegre : Instituto Anchietano de Pesquisas, 1957. (Pesquisas, I)

. Os Munku : 2.ª contribuição ao estudo da tribo Irantxe. Porto Alegre : Instituto Anchietano de Pesquisas, 1960. 60 p. (Pesquisas, Antropologia, 10)

- MOURA E SILVA, José de (Pe.); PEREIRA, Adalberto Holanda (Pe.). História dos Múnku (Irantxe). Porto Alegre : Instituto Anchietano de Pesquisas, 1975. 40 p. (Pesquisas, Antropologia, 28).

- NEWMAN, Marshall T. Anthropometry of the Umotina, Nambicuara, and Iranxe, with comparative data from other norther Mato Grosso tribes. Washington : United States Government, 1953.

- OPAN. Diagnóstico na Terra Indígena Irantxe Estado de Mato Grosso : Relatório final. Cuiabá, Opan, 2000.

- PEREIRA, Adalberto de Holanda (Pe.). Lendas dos índios Iranxe. Porto Alegre : Instituto Anchietano de Pesquisas, 1974. 84 p. (Pesquisas, Antropologia, 27)

. O pensamento mítico Iranxe. São Leopoldo : Instituto Anchietano de Pesquisas, 1985. (Pesquisas, 39)

- PIVETTA, Darci Luiz. Processo de ocupação das dilatadas chapadas da Amazônia Meridional : Iranxe - educação etnocida e desterritorialização. Cuiabá : UFMT, 1993. 250 p. (Dissertação de Mestrado)

. Trágico destino : extermínio e escravidão. Cadernos do Neru, Cuiabá : UFMT, n. 2, p. 141-63, dez. 1993.

- PIVETTA, Darci Luiz; FREIRE, Maria de Lourdes Bandeira Delamônica. Iranxe : luta pelo território expropriado. Cuiabá : UFMT, 1993. 185 p.

- RONDON, Cândido M. da Silva. Conferências realizadas em 1910 no Rio de Janeiro e São Paulo : Comissão de Linhas Telegráphicas Estratégicas de Matto Grosso ao Amazonas, Rio de Janeiro : Comissão Rondon, 1946. (Publicação n. 68). A 2a. edição, publicada pela Imprensa Nacional, Rio de Janeiro.

. Conferências realizadas nos dias 5, 6 e 9 de outubro de 1915 : sobre os trabalhos da Expedição Roosevelt e da Comissão Telegraphica. Rio de Janeiro : Comissão Rondon, 1916. (Publicação n.42).

. Índios do Brasil. v.2: Cabeceiras do Xingu, Rio Araguaia e Oiapoque. Rio de Janeiro : CNPI, 1953. 326 p.

- ROOSEVELT, Theodore. Nas selvas do Brasil. Belo Horizonte : Itatiaia ; São Paulo : Eudsp, 1976.

- ROQUETTE-PINTO, Edgard. Rondônia. São paulo : Cia. Editora Nacional ; Brasília : INL, 1975. 285 p. (Brasiliana, 39)

- SANCHEZ, R. O. Zoneamento agroecológico do Estado de Mato Grosso. Cuiabá : Fundação de Pesquisas Cândido Rondon, 1991.

- SCHMIDT, Max. Los Iranche. Rev. de Cincias Fsicas, Naturales y Matemticas, s.l. : Sociedad Cientfica del Paraguay, v.5, n. 6, p. 35-44, 1942.

. Los Paressis. Rev. de Cincias Fsicas, Naturales y Matemticas, s.l. : Sociedad Cientfica del Paraguay, v. 6, n. 1, p. 1-226, 1943.

. Resultados da minha expedio bienal a Mato Grosso de Setembro de 1926 a Agosto de 1938. Boletim do Museu Nacional, Rio de Janeiro : Museu Nacional, v. XIV-XVII, p. 241-85, 1938-1941.

VÍDEOS