Guajá

- Self-denomination

- Awa

- Where they are How many

- MA 520 (Siasi/Sesai, 2020)

- Linguistic family

- Tupi-Guarani

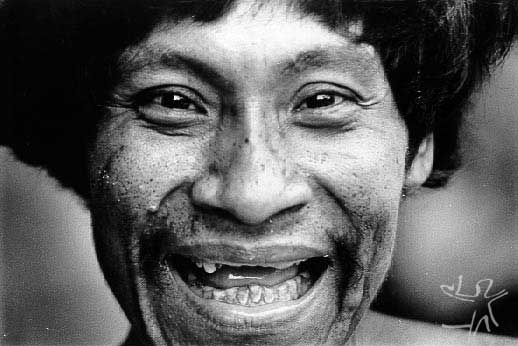

The Guajá reside in Brazil's pre-Amazon region and are one of the last groups of hunter-gatherers of Brazil, and the world. In addition to those Guajá who were contacted and settled by Brazil's Indian Service (FUNAI), an unknown number are still uncontacted and live in the adjacent forested areas of this region.

Further reading

The Awá Indians of Amazonian Brazil: the most endangered tribe on earth @ Vanity Fair Magazine

Name and Language

The Guajá call themselves Awá, a term which means "man", "person", or "people". Their origins are obscure yet it is believed that they came from lower Tocantins river basin of Pará state. They probably formed part of a larger group composed of other Tupi-Guarani peoples, such as the Ka'apor, Tembé, and Guajajara (Tenetehar) (Gomes 1988, 1989 & 1991; Balée 1994). As European colonial settlement expanded, exerting pressure on local indigenous populations, these groups were forced to disperse. With the advent of the Cabanagem upheaval, around 1835-1840, they steadily moved in an easterly direction, towards the state of Maranhão. It is likely that by 1950 all of the Guajá were already residing east of the Gurupi river, which separates Pará from Maranhão state (Gomes 1989 & 1991).

Location

The Guajá that are in permanent contact live on the Alto Turiaçu (530,520 hectares) and Caru (172,667 hectares) Indian Reserves; both of these areas have been officially demarcated and registered. Since 1982 there has been an attempt to establish a new land area for the Guajá, known as the Awá Indian Reserve. The establishment of this reserve would link up the Alto Turiaçu and Caru Reserves, thus creating a contiguous land area less prone to invasion by local settlers. In addition to providing more security for the Guajá, the consolidation of these areas would give them more land to carry out their traditional subsistence activities. The establishment of the Awá Reserve would also deed them a land area of their own since they currently share the Alto Turiaçu and Caru Reserves with the Ka´apor, Timbira e Guajajara. Moreover, it is believed that some uncontacted Guajá reside in this area such that its demarcation would extend protection to these groups as well. Some stretches of this would-be Reserve have been deforested, not to mention that some feeder roads are already cutting through the area, serving as a conduit for the illegal extraction of lumber. Thus, it is extremely important that this Reserve be demarcated and registered to guarantee a more secure future for the Guajá. The last official document addressing the issue of a future land area for the Guajá was Brazil's Official Daily Bulletin (Diário Oficial da União), posted on July 29, 1992, by its Ministry of Justice, designating approximately 118,000 hectares for the future Awá Reserve. However, till this day, demarcation has not gone forward as powerful regional interests, wielding much political and economic power, have steadily lobbied against the establishment of the Awá Reserve.

Other groups of uncontacted Guajá were sighted on the Arariboia Indian Reserve, by the Guajajara Indians, to the south of the Alto Turiaçu and Caru Reserves. Other sightings of uncontacted Guajá were reported on the Gurupi Biological Reserve, adjacent to Caru Reserve, to its west. As it happens, other uncontacted groups were also seen on the Alto Turiaçu and Caru Reserves, as well as some of their vestiges, such as abandoned campsites, as reported by the Ka'apor and contacted groups of Guajá. Additionally, more distant groups have been seen trekking on sierras linking up the states of Maranhão, Tocantins, Piauí, Goiás, Bahia e Minas Gerais. In fact, this natural corridor has served as a refuge for some Guajá groups and it has safely conducted some individuals to Bahia and Minas Gerais. The Guajá's passage through this area is an example of their capacity to adapt to different ecosystems and adverse conditions in their quest for survival.

Demography

Contact was not a positive experience for the Guajá as they suffered heavy population losses. For hunter-gatherers in general the archeological record also shows that the transition from hunting and gathering to agriculture brings on many complications for newly settled groups. Permanent settlement has many health implications in terms of poorer diets and infectious diseases brought on by poor sanitary conditions and denser populations. But the Guajá case is unique, although similar to many other indigenous groups in modern history, in that they fell prey to contagious diseases incurred by FUNAI's contact agents and other elements of the encroaching frontier. In one particular outpost, Post Guajá, situated on the Alto Turiaçu Reserve, contact was conducted in a haphazard manner and, as a result, between 1976 and 1980 roughly 67 individuals died out of a population of 91 people. Most of these deaths came from malaria and influenza. This particular community has slowly recovered from these losses and currently has a population of 60 people.

One of the consequences of this demographic decline among the Guajá is the disparity in their sex ratios. At one time there was a disproportionate sex ratio of three men to one women of reproductive age at both Posts Guajá and Juriti, the latter located on the Caru River, situated on northern limits of the Caru Reserve. This disparity has created a number of polyandrous associations, where one women cohabits with two or more men, a situation similar to that encountered among the Suruí from Tocantins. Apparently, this type of union represents a Guajá effort to recover from population losses. At Post Awá the demographic structure was more intact and marriages among members of this community were generally more monogamous, although there were some incidents of poligynous marriages.

Currently there are approximately 234 Guajá residing on four semi-nucleated settlements aministered by FUNAI on the Alto Turiaçu and Caru Reserves, located near Posts Guajá, Awá, Juriti and Tiracambu. There is no definite consensus as to the number of uncontacted Guajá, yet it is believed that it is no more than 30. Prior to this inference, population estimates were larger for the number of uncontacted Guajá. Although former population figures for uncontacted Guajá were higher, these latter calculations could have been inflated in a FUNAI effort to draw more resources to its Guajá Program. Additionally, as regional settlement encroaches upon them, more Guajá groups will be contacted and those that remain uncontacted can fall easy prey to hostilities and disease, without any outside observer ever having knowledge of their whereabouts.

Subsistence activities

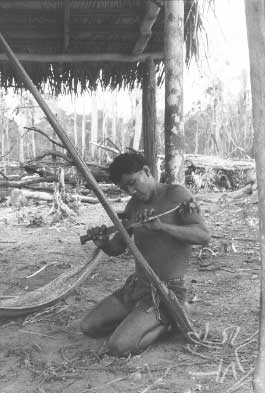

The Guajá came into permanent contact with Brazilian mainstream society in 1973. It is speculated that until then they lived a nomadic life, subsisting primarily from hunting game animals and gathering forest products. Yet it is possible that they were horticulturalists in the past until being forced to adopt a nomadic lifeway due to pressure from other local indigenous groups that had a numerical advantage over the Guajá.

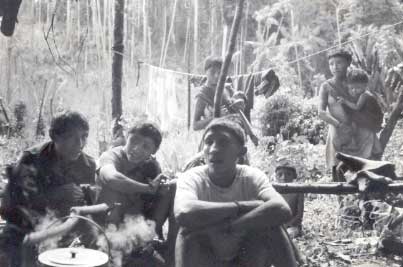

Under FUNAI's orientation the Guajá currently practice shifting cultivation, thus engaging themselves in a subsistence pattern similar to that of their non-indigenous neighbors located outside their reserves. They adapted quickly to this subsistence strategy as it provides them with yet another option in their food spectrum. Furthermore, settlement near FUNAI posts turned out to be somewhat advantageous for the Guajá as they now have access to western medicines to treat introduced diseases. This situation represents one of the "upsides" of contact although, in the main, contact only brought on illness, disease and stress. Nevertheless, hunting and gathering have not ceased to be a premier subsistence strategy among the Guajá as they frequently leave their newly formed villages to visit their hunting camps in the forest. Although the bulk of their diet now comes from farming, hunting occupies most of their time in terms of subsistence activities.

There are large expanses of babaçu palm (Attalea speciosa) forests in the general Guajá habitat. This palm is abundant throughout the region and thrives in the process of forest succession, frequently dominating the landscape in the wake of old agricultural plots. Babaçu serves a multitude of purposes for the Guajá, and its fruit serves as a hedge against starvation as well as providing an important supplement to their diet, as it is rich in oil and protein. Before permanent contact, it was common for the Guajá to camp in tracts of forest dominated by babaçu stands to gather it fruits.

In addition to their crops, another item that has increased in the Guajá diet is fish. Before permanent contact, they were more prone to occupying headwater and interfluvial areas, such that fishing was not a very productive activity. After contact, they now reside near some of the main watercourses of Maranhão state (Pindaré, Caru e Turiaçu), a situation which now permits them to better utilize riverine and lacustrine resources.

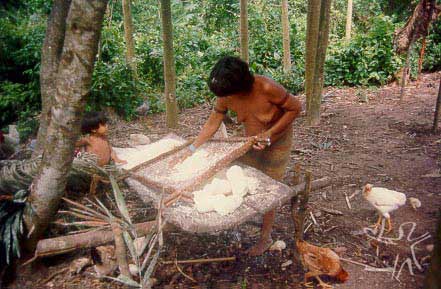

Another factor that made horticulture attractive to the Guajá is that many of their crops come into season during the rainy period, normally when game and other forest products become scarce. An anthropometric study revealed that some communities exhibit a higher fat-to-lean-mass-ratio during the rainy season in comparison to the dry period. This situation occurs because of the large amount of consumed manioc flour (farinha) in the wet period along with palm fruits rich in oil and protein, such as bacaba (Oenocarpus distichus). Similarly, during this period they can afford to be less active as they can fall back on their crops when hunting becomes scarce. They now grow a host of farm products such as manioc, rice, corn, sweet potatoes, yams, bananas, melons, watermelons, beans, and squash, and also have access to fruits grown on FUNAI's orchards (i.e., mangoes, bananas, oranges, cacau, passion fruit and others).

Social organization

During the span of their lifetimes, both men and women can have a number of successive marriages. There is no preferential type of marriage arrangement among the Guajá although some anthropologists believe that they exhibit a Dravidian type of kinship system, where preferred partners would be cross-cousins. However, subsequent observations reveal that this is not the actual type of social organization among the Guajá. Perhaps this speculation comes from the fact that some referential kinship terms appear similar to other Tupi-Guarani groups of the eastern Amazon region, embracing the Ka´apor, Tembé and Guajajara (Tenetehar), all of these formerly constituting part of a larger group along with the Guajá, as mentioned previously. In this respect it becomes difficult to reconstitute the Guajá's former kinship system as many these groups disperesed and were reduced to mere fragments of their former population.

Before permanent contact was established with FUNAI, it is presumed that the Guajá resided in Maranhão's pre-Amazon region in groups of 5 to 30 individuals. Some of them migrated southward to areas very distant from their original habitat, as was the case of two Guajá men who were found in the states of Bahia and Minas Gerais, respectively. One of them, Karapiru (Hawk), became a feature story in a local TV program in Belém, Pará, on its TV Cultura network. In 1978, Karapiru and his family were ambushed by gunmen in a farm in near Porto Franco, Maranhão, and as a result, they were forced to scatter and run. He survived alone in the forest, trekking for a period of 10 years, in a southerly direction, and was eventually found near a farm in Bahia in 1988.

FUNAI's attraction front brought many Guajá groups together that were unfamiliar with one another. Many of these people were settled together in the same village, a situation which could have altered their social organization. While cross-cousin marriage is permitted among the Guajá they currently prefer to find marriage partners among non-related people. In this respect, perhaps it would be more appropriate to characterize their unions as a form of "alliance" between groups that were once hostile to one another. In some cases, FUNAI itself has acted as a mediator in arranging marriages between people from different villages. Likewise, since the animosity that existed between the Guajá and Ka'apor was appeased by FUNAI in the 1970s, interaction between them is now friendly, such that a Guajá man from Post Guajá married a woman the the Ka'apor village of Urutawy, on the Alto Turiaçu Reserve. Also under FUNAI's influence a Guajá man was married twice to non-Indian peasant women from hamlets nearby the Caru Reserve. In the latter case, the person in question mentioned that he was "ashamed" to be an Indian and that he preferred white women to indigenous women.

Religion

The Guajá practice a form of animistic religion and believe that the spirits of their ancestors and other spiritual beings reside in a celestial paradise. During the dry season, during full-moon nights, Guajá men are adorned by their women with toucan feathers and vulture down to visit this sky world and commune with these spirits (ohó iwa-beh).

The men sing and dance around a hunting blind (takaia) built in the village clearing, with babassu palm fronds (a variant of this term, tocaia, was taken from Brazil's língua geral, formerly Tupi, and incorporated in the Portuguese language, to signify a contraption made for ambushes and hunting). Each man enters the takaia individually and, once inside, they sing and dance and then finally thrust themselves to the skyworld with a strong pounding of their feet. Once they enter the spirit world they encounter their forebears and other spiritual entities.

As such, they interact with the spirits and perform an exchange with them to return to earth. Thus, upon descending to earth the men return by incorporating one of the spirits. Once they return, the men dance in the direction of their wives and family. As they near their families, they begin to communicate by singing and "bless" their family members by blowing on them. Later, their wives ask for the presence of other spirits and, in turn, the men return to the spirit world in the sky to bring back these other entities. Although the spirit world is a man's domain it is the women who direct the event by requesting that their men call on particular spirits for curing divining. For their part, the men serve as a vehicle and link between the celestial paradise and the earth.

Notes on the sources

This entry is based on information obtained through the bibliographical sources listed below, and on field research carried out between 1991 and 1994, which lasted a total of eighteen months. More recent information comes from the CIMI (Maranhão) and the Funai (Brasília and ADR Belém). The literature contains two kinds of sources: one refers to material that deal specifically with the Guajá, written by myself (1995a & b, 1996, 1997, 1998), Nimuendaju (1949) and Mércio Gomes (1989 and 1991), and other works that added information about them".

Sources of Information

- BALÉE, William L. Footprints of the forest : Ka’apor ethnobotany - the historical ecology of plant utilization by an Amazonian people. New York : Columbia University Press, 1994.

- --------. People of the fallow : a historical ecology of foraging in lowland South America. In: REDFORD, Kent H.; PADOCH, Christine J. (Eds.). Conservation of neotropical forests. Nova York : Columbia University Press, 1992. p. 35-57.

- --------. The persistence of Ka’apor culture. New York : Columbia University, 1984. 290 p. (Tese de Doutorado)

- CUNHA, Péricles Luiz. Análise fonêmica da língua Guajá. Campinas : Unicamp, 1987. 68 p. (Dissertação de Mestrado)

- FORLINE, Louis Carlos. Indigenous peoples and state players in Amazonia : implication of contact, settlement and food security among the Guajá indians of Maranhão state, Brazil. Poematropic, Belém : Poema, v. 1, n. 1, p. 26-33, 1998.

- --------. Os índios Guajá : sua situação alimentar face ao contato e sua transição à agricultura. In: VERDUM, Ricardo (Coord.). Mapa da fome entre os povos indígenas no Brasil (II) : contribuição à formulação de política de segurança alimentar sustentáveis. Brasília : Inesc ; Rio de Janeiro : Peti/MN ; Salvador : Anaí-BA, 1995. p. 71-3.

- --------. A mulher do caçador : uma análise a partir dos índios Guajá. In: ALVARES, Maria Luzia M.; D'INCAO, Maria Ângela (Orgs.). A mulher existe? Uma contribuição ao estudo da mulher e gênero na Amazônia. Belém : MPEG, 1995. p. 57-79.

- --------. The persistence and cultural transformation of the Guajá indians : foragers of Maranhão state, Brazil. Gainesville : University of Florida, 1997. (Tese de Doutorado)

- --------. El pueblo Guajá y la palmera Babaçu (Orbignya martiana). Desarrollo Agroflorestal y Comunidad Campesina, Salta-Argentina : s.ed., v. 1, n. esp., p. 36-41, 1996.

- GOMES, Ivanise P. Aspectos fonológicos do parakanã e morfossintáticos do awá-guajá (tupi). Recife : UFPE, 1991. 120 p. (Dissertação de Mestrado)

- GOMES, Mércio Pereira. Os índios e o Brasil. Petrópolis : Vozes, 1988.

- --------. O povo Guajá e as condições reais para a sua sobrevivência. In: RICARDO, Carlos Alberto (Ed.). Povos Indígenas no Brasil : 1987/88/89/90. São Paulo : Cedi, 1991. p. 354-60. (Aconteceu Especial, 18)

- LARAIA, Roque de Barros. "Arranjos poliândricos" na sociedade Suruí. In: SCHADEN, Egon. Leituras de etnologia brasileira. São Paulo : Companhia Ed. Nacional, 1976. p. 193-8 (Originalmente publicado na Rev. do Museu Paulista, São Paulo : Museu Paulista, v. 14, n.s., p. 71-6, 1963)

- NIMUENDAJÚ, Curt. The guajá. In: STEWARD, J. (Ed.). Handbook of South American Indians. v. 3. Washington : U.S. Government Printing Office, 1949. p. 135-6.

- SILVEIRA, Maria Luiza dos Santos. Identidade em mulheres índias : um processo sobre processos de transformação. São Paulo : USP-IP, 2001. 377 p. (Dissertação de Mestrado)

- TREECE, Dave. Bound in misery and iron : the impact of the Grande Carajás Programme on the indians of Brazil. Londres : Survival International, 1987.

VIDEOS