Yawalapiti

- Self-denomination

- Where they are How many

- MT 309 (Siasi/Sesai, 2020)

- Linguistic family

- Aruak

The Yawalapiti live in the southern part of the Xingu Indian Park, a region which has become known as the Upper Xingu, where different language-speaking groups in large part share the same cosmological repertoire, have similar ways of life and are interconnected through commercial trade, marriages and inter-village cerimonies. While general information on the Upper Xingu may be found on the page dedicated to the Park, this section reports on aspects of the Yawalapiti version of the Upper Xingu world, as well as several specific characteristics of this group.

Name and location

The name Yawalapiti means "village of the tucum palm trees" and is today used as a self-designation. The "village of the tucum palms" would be the most ancient location which they remember and is situated between the Diauarum Post and the Morená reef (a site near the confluence of the Kuluene and Batovi rivers). The present Yawalapiti village is situated more to the south, where the Tuatuari and Kuluene rivers meet, a place of fertile land, about five kilometers distance from the Leonardo Villas Bôas Post.

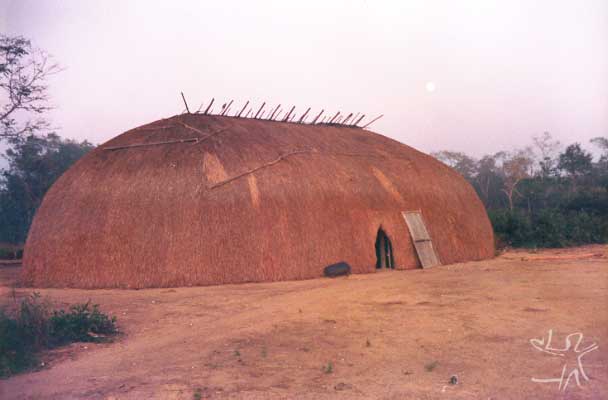

Village and daily life

Following the upper Xinguan pattern, the Yawalapiti village is circular, with all the communal houses arranged around a plaza which is cleared of forest growth. In the center of the plaza (uikúka) there is a house which is frequented only by the men and is specifically the place where the sacred flutes apapálu are hidden. It is in this house, or on the benches in front of it, that the men get together to chat at dusk, and where they paint themselves for the cerimonies. The house of the flutes is built much like the communal houses, but it has only one or two doors, facing the center of the plaza, which are always smaller than the doors of the communal houses. The flutes are kept hanging from the main beam and during the day they have to be played inside the house; but at night (when the women have retired) the men can play them on the plaza.

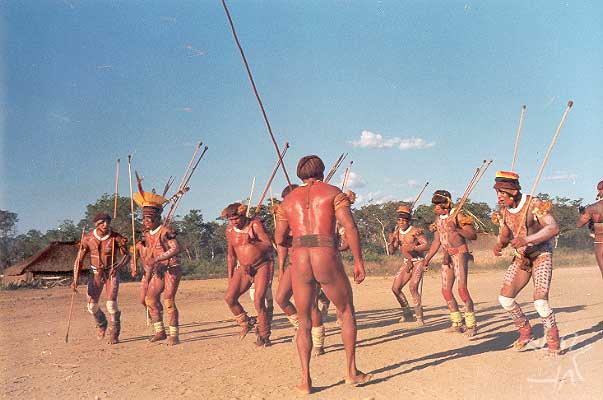

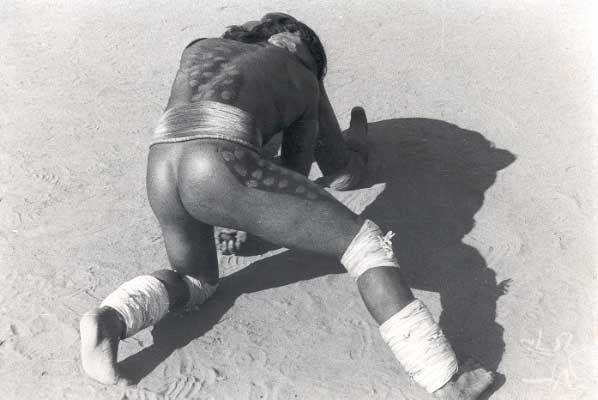

The plaza is also the place where the dead of both sexes are buried, in a tunnel that connects two holes, where two poles are set that hold the hammock of the dead (who lies in the tunnel) in place, for the dead amulaw (hereditary category of prestige associated with the positions and functions of leaders and chiefs), or a simple grave (pawá uti, "a hole") for the dead who are not amulaw. In the center of the uikúka the ritual baths that end mourning are held; it is there that the chief makes his speeches and exhortations; it is there that foods are distributed during the cerimonies; there, visitors from other groups are received, especially the formal messengers, who do the inviting to the intergroup cerimonies of the peoples of the upper Xingu. The center is also the place where the members of these different villages face each other physically, in the sportive wrestling matches called karí (or huka huka, in Kamaiurá terminology, as the matches have become best known).

Women rarely go to the uikúka, except on certain cerimonial occasions, when sex roles are inverted (as in the Amurikumálu, which is called Yamurikumã, in Kamaiurá, see the section on the Xingu Indigenous Park, just avaiable in Portuguese version), or when young girls ending their initiation seclusion are presented to society for the first time. The center is the place of visibility par excelence, in contrast with the seclusion compartment. To go to the center is to make the social person public " the emergence of the boys and girls from their seclusion compartments is a movement from the periphery (inside the seclusion compartments, which are located inside the houses) to the center. (For more on puberty seclusion in the upper Xingu, see the item "Village and society" in the section dedicated to the Park).

Manioc is planted by the men who cut down the forest, burn and clean the gardens. Gardens are individual property, belonging to the men, and are assumed as soon as a young man enters into seclusion (14-17 years). These property rights do not apply to the land as such, but only to the manioc plantation. The women pull up the roots, carry them, scrape them and squeeze out their poisonous juice. Manioc is basically consumed in the form of bread (beiju, ulári) " toasted flour, flatcakes, toasted in circular pans -, porridge made with beiju dissolved in water (uluni), and a porridge which is produced by boiling the poisonous juice (nukaya). The flour that remains at the bottom of the pans for squeezing, as well as part of the mass, is stored in silos in the center of the houses.

As for fish, cooking is done by both men and women; the processing of the manioc after it is planted, however, is entirely female work. The women are also in charge of fetching water for the village. It is they who spin cotton " also planted - , weave the hammocks and the mats for squeezing manioc, and prepare the urucum (red vegetal dye) paste, piquí oil and jenipapo dye, used in body ornaments. The men make the baskets, the cerimonial instruments (flutes and rattles), and take care of all the work in wood (benches, bows, mortars, scoops for turning over the beiju etc.). It is also the men who build the houses.

Language

The Yawalapiti language belongs to the Arawak language family, along with the Mehinako and Wauja languages, also spoken in the Park. Presently, only four or five individuals speak Yawalapiti, and the languages that predominate in the village are Kuikuro (of the Karib language family) and Kamaiurá (of the Tupi-Guarani family), due to the numerous marriages that link the Yawalapiti to these groups. But the Yawalapiti have shown a growing interest in recovering their language and for that reason they have relied on the assistance of a linguist. They even wish to build an indigenous school and, in 2002, they sent representatives to participate in the course for Training of Indigenous Teachers sponsored by the ISA in the Park.

History

The first historically recorded contact of the Yawalapiti with non-Indians occured in 1887, when they were visited by the Karl von den Steinen expedition. At that time, they were located on the upper course of the Tuatuari River, in a region situated among lakes and swamps identified by the Yawalapiti as the site of many of their villages. The German ethnologist was impressed with the poverty of these Indians, who hardly had any food to offer to the visitors; the Yawalapiti identify this period as the beginning of their decline as a group, which would culminate in the dissolution of the village in the 1930s. Von den Steinen mentions two Yawalapiti chiefs, Mapukayaka and Moritona (possibly Aritana), names which are still present today in the genealogy of these people, who are able to trace their ascendence to these same contemporaries of von den Steinen.

The Yawalapiti relate how they left the "village of the tucum palms", near the juncture of the Kuluene and Batovi rivers, due to the attacks of the Manitsawá " or, several say, the Trumai " who decimated a great many of them. Tatîwãlu, chief of this village and a very distant historical ancestor of the Yawalapiti, died there. His brother Waripirá and his "cross-cousin" (italuñiri) Yanumaka came up the Kuluene, leading the remaining Yawalapiti. At the mouth of the Tuatuari, there was a division of the group: Yanumaka went on up the Tuatuari and Waripirá went to the headwaters of the Kuluene. Yanumaka’s group settled in Yakunipi, the first village of the present-day Yawalapiti.

Due to their population growth, the Yawalapiti of Yakunipi built other villages in the region known as Puía ("Lake"), a triangle of highlands between lakes and groves of buriti palms fed by a branch of the Twatwarí. The largest village there was Ukú-píti ("village of the arrows"), an ancient Mehinako site, abandoned by them due to spirits who infested the lakes and stole children.

In the mid-1940s, after having occupied the site of Palusáya-píti (previously associated with the Mehinako), the Yawalapiti suffered a serious crisis, which led to a temporary dispersion of their population among the Kuikuro, Mehinako and Kamaiurá villages. At the time of the arrival of the Villas Boas brothers in the region, the Yawalapiti had rebuilt their villages, re-organizing themselves as a group. Between 1948 and 1950, they re-organized on the ancient site of the lakes (Puía), from whence they left (at the suggestion of the Villas Bôas) at the beginning of the 1960s, then moving to Emakapúku, near the Leonardo Post. Presently in the village, besides the "original" Yawalapiti nucleus, there are Kamaiurá, Kuikuro, Kalapalo, Wauja and Mehinako Indians.

Population

In 1948, immediately before the regrouping of the Yawalapiti, Oberg (1953:44) counted 28 individuals; in 1954, during the measles epidemic which devastated the region, there were 25; in 1963 they totalled 41 individuals; and in 1970 they had increased in number to 65 (Agostinho 1972:259-260). Since then there has been a progressive population increase, not only due to the spontaneous growth of the group " stimulated by the health services in the Park and the decrease in conflicts between the peoples of the upper Xingu and their neighbors, as a result of the "pacification" work done by the Villas Bôas brothers -, but also to the incorporation of members from other villages, an ancient custom in the region, which intensified with the creation of the Park. Orlando and Cláudio Villas Bôas stimulated marriages with other peoples, principally with the Kamaiurá, Kuikuro and Mehinako. Although the Kuikuro and Kamaiurá languages predominate, at times the "men’s house" of the village includes speakers of nearly all the languages of the upper Xingu.

In 2002, the Yawalapiti, according to data of the Unifesp, totalled 208 individuals.

Social organization

The "owner of the village", putaki wikiti, today corresponds to the chief, and among his attributes is that of representing the local group in cerimonial interaction with other ethnic groups, orating in the center of the plaza on receiving messengers from other groups and giving counsel to the villagers to follow the models of upper Xingu ways of life. The putaki wikiti is usually chosen among the amulaw, who comprise an hereditary class of individuals of prestige, often leaders of domestic groups ("house owners"), who have special privileges in inter-village cerimonies.

The classical residence pattern of the Upper Xingu is that chiefs and individuals of prestige, such as members of the categories corresponding to the Yawalapiti amulaw, live virilocally (the woman lives in the house of her husband’s family), while the "common people" should go through an uxorilocal stage (the husband lives in the house of the wife’s father) before taking up virilocal residence. This model nonetheless is flexible, for, in the case of the amulaw of prestige, it can happen that the sons-in-law are kept definitively at their wives’ homes (thus producing a situation of permanent uxorilocality); there are also domestic groups formed by men who exchange sisters, including daughters’ husbands; and even houses comprised only by nuclear families, ocasionally with the widowed father/mother of one of the spouses.

Among the Yawalapiti, as well as among other peoples of the upper Xingu, the relations based on the sharing of physical substance, established through procreation, are important in the formation of social groups and categories. Thus, parents, children, and brothers/sisters (but not spouses) are connected throughout their lives by ties of corporal identity, and are thus affected by what occurs in each others’ bodies. Because of this identity, for example, the parents of young children and the near kin of sick people must submit to food tabus.

Children are conceived, according to the Yawalapiti, through repeated sexual activity between a man and a woman. In fact, more than one man may contribute to the formation of the child, and also be recognized as genitor.

The substance that forms the body of the child originates exclusively from the male sperm, which "cuts"or "shuts off" the blood that the women have inside their bellies; the blood then will "become round" inside the woman and form the fetus. The role of the mother is essentially to receive the semen inside her and to guarantee the pre-natal development of the child. The relations of substance between mother and child develop through feeding: what she eats feeds the child, in the same way her milk does, after birth.

Within the domestic group, relations of substance are also recognized independent of the kinship ties created through procreation, relations that are based on living and eating together; the beginning of menstruation of any woman in the house, for example, implies the destruction of all food and water present there.

Cosmology and rituals

For the Yawalapiti, the mythic world is a past that is not connected to the present through strict chronological ties. Thus, myth exists as a spatial and temporal reference, but mainly provides behavioral models. The cerimonies are the occasion par excelence for replicating these models, but their privileged relation with the world of myth above all symbolizes the impossibility of repeating that world, except in an imperfect way. The ritual is thus a moment when daily life is closer to the ideal model presented in myth, without however being able to attain it. (The principal rituals of the upper Xingu are discussed on the page Xingu Indigenous Park, just avaiable in Portuguese version).

According to Yawalapiti mythology (which shares the upper Xingu cosmological repertoire), the primordial making of humans was undertaken by the demiurge Kwamuty, who, on blowing tobacco smoke over wooden logs placed in a seclusion compartment, brought them to life. He thus created the first women, and among them the mother of the twins Sun and Moon, prototypes and authors of present-day humanity. This woman was the first mortal in whose honor the first festival of the dead, itsatí (or kwarup, in kamaiurá), the principal inter-village ceremony of the upper Xingu (described on the page dedicated to the Park) was celebrated.

When the twins Sun and Moon were born of this woman, it was a time of chaos, dominated by night and rottenness (the birds defecated on people), with no fire nor gardens. The fireflies were the only light that men had. The twins then succeeded in obtaining the day from the "owner of the sky" (añu wikiti), the invisible two-headed vulture, attracting it by means of rotten bait. This vulture commands the birds, who gave day (the light) to men, in the form of adornments made of red macaw feathers (the mythical sun uses a headdress and armbands made of feathers of this bird).

Most of the Yawalapiti rituals originated from the visit of a human to one of the domains "earth, water and sky" that constitute well-defined spheres in Yawalapiti classification, defining the main lines of animal classification and possessing distinct cosmological values. The earth is diversified, according to vegetation and reference to mythic events. The principal distinction in this domain is between the "forest" (ukú), where the animals and spirits live, and the village (putaka), where humans live. In the rivers (uiña) and lakes (iuiá), besides the fish, most of the spirits who are important to the Yawalapiti dwell. In the sky (añu naku; añu taku) the souls of the dead reside; it is the realm of the birds, whose chief is the two-headed vulture, "owner of the sky". In the "belly of the earth" (wipiti itsitsu), below the ground, there is a spirit-woman, who is fat and has only one breast; she breastfeeds the female dead and copulates with the male dead; she is the "owner of the earth".

The category of "people" (ipuñiñiri), , according to Yawalapiti cosmology, differentiates "Indians" (warayo) from "Whites" (caraíba), both in their physical appearance (which means that Japanese and Chinese are classified as warayo-kumã: "other Indians", "Mysterious Indians") and material culture. Among the Indians, the groups of the upper Xingu are considered a unit (putáka), in contrast with other peoples. The warayo in general are differentiated from the putáka by the fact they have different eating habits - all eat apapalutapa-mina, "terrestrial animals" -, they are "wild" (Kañuká) and unpredictable, and by the way they cut their hair, and their adornments. Warayo is a term that is used in a pejorative sense by the Yawalapiti when someone does something shameless (parikú).

Besides sharing a series of customs, conceptions, and inter-societal rituals, another distinguishing feature of the Indians of the upper Xingu is an ideal of respectful and prudent behavior, the key categories for which, in the Yawalapiti version of things, are parikú (shame) and kamika (respect). Parikú refers to a psychological state of the individual, which is usually activated when there occurs a transition or confusion in roles "such as among those in seclusion or between potential spouses- or hierarchical inferiority" such as between son-in-law and father-in-law, or in the case of women in the midst of men. Kamika in turn is a feature of certain social relations and roles, referring to peaceful and predictable behavior, as well as to generosity and respect for affines and those who are in hierarchically superior positions. It is respect, but it is also "fear", in the sense of avoiding dangerous things. In contrast to the kamika typical of upper Xinguan peoples, which is associated with the adjective mañukawã ("tame", "calm"), there is the behavior called kánuká, violent and unpredictable, which is typical of the warayonaw (Indians from outside the upper Xingu).

Shamanism

The Yawalapiti postulate the existence of a multiplicity of spiritual beings that have considerable influence over human affairs: they cause most sicknesses, they meet humans in the forest, they help shamans and they are the "owners" of certain animal species. In general, there are two classes of spirits: the kumã-beings, who are the transcendent doubles of animal species and classes of daily objects; and the apapalutápa, who have specific names, and correspond more vaguely with the entities of the daily world (including the thunder, the lightning bolt and spirits with a peculiar form). In both classes, it is common to find the idea that the spirits possess an anthropomorphic essence beneath a monstrous appearance, which is concretely thought of as a piece of clothing or covering (iná). The spirits are invisible, munukinári; they only appear to the sick and to the shamans in transe. To see a spirit by accident (always when one is outside the village) in itself provokes sickness or death.

The apapalutápa are usually in all parts, except inside the village, where they appear only in extraordinary situations of sickness, shamanism and ritual. Two figures of human society maintain a special relation with the apapalutápa: the shamans and the sorcerers. Every spirit is by definition an iatamá, shaman. Several are shamans specific to certain animal orders, but "shaman" and "spirit" are to a certain degree synonymous.

The relations of the apapalutápa with Yawalapiti society are predominantly individual, in the basic form of sickness. Except for the evils caused by sorcerers, who can, otherwise, avail themselves of the help of spirits, all sicknesses derive from contact with the supernatural world. The sick person is someone who has "died" (kuká inukakína, which is equally said of the shaman in transe) from the actions of an apapalutápa. Such a state is due to the penetration of invisible darts in the body, which the shaman extracts and displays in the curing session. It can also be caused by a stealing of the soul (ipaïori) by the spirit, which takes it (the soul) to the village of the apapalutápa. This theft is experienced by the sick person as an especially intense dream journey (every dream or feverish delirium is a journey of the soul); it ends when the shaman replaces the soul with the help of a doll (yakulátsha: from yakulá, "shade", "soul of the dead") thought of as an image of the sick person.

Once cured, the individual then owes something to the spirit that he saw. He then must sponsor a cerimony in which he represents the spirit by means of songs, dances and corporal paintings or adornments. This ceremony is the moment in which the group of substance to which the sick person belongs (which tends to be a unit of daily production) distributes food to the entire village. The spirit is incarnated-represented by the community, and both are fed by the group which, ideally, has fasted during the period of sickness: the food distributed is said to be "(name of the spirit) inúla". The sick person becomes the patron of the cerimony (wököti), and does not participate as an actor in it.

The shaman thus exercises social control over the relations between the village and the supernatural world: he regulates the relations between men and spirits who inhabit the waters and forest; through his diagnoses, the sickness-causing spirits are socialized through ritual. The sorcerer, in turn, represents the paradigm of the marginal being: he is the backdoor man, who invades the houses, who puts sorcery on the gardens, who transforms into an animal in the forest.

The shamanic vocation comes from a sickness in which a spirit appears and gives tobacco to the novice, teaching him songs and medicines. Pepper and tobacco are said to be Kahiúti, painful or burning hot, and constitute part of the specific diet of the shamans. Tobacco is the preferred substance of the spirits, who appreciate its sweet smell örö (which contrasts with blood and genital fluids, which the spirits detest) and is a supreme transforming agent. The demiurge Kwamuty made the first humans by blowing tobacco over wooden logs; the Sun revived the Moon by fumigating him. There are numerous episodes in the myths where tobacco gives life, mends and remakes. The apapálu flutes, originally aquatic spirits, were captured by using pepper and above all tobacco.

Productive activities

The Yawalapiti, like other peoples of the upper Xingu, live basically by agriculture and fishing. Hunting is reduced to a few birds that are considered edible (jacu, curassow, macuco, dove), monkeys that are occasionally eaten, and to the acquisition of feathers for ornaments; certain birds are also raised as pets. Agriculture is focused on the cultivation of wild manioc (maniot utilissima), but other varieties of manioc are planted in lesser quantity. Corn, bananas, several species of beans, pepper, tobacco and urucum are among the several other cultivated species.

Fishing is a masculine activity par excelence; the rivers of the region are abundant in fish and, during the dry season, when the rivers are low, the Yawalapiti use nets (which are not indigenous in origin), hooks, arrows and fish poison (a liana the pulp of which asphyxiates the fish) to obtain this food. The fish can be roasted directly in the fire, grilled (placed on grills over a slow fire) or cooked.

The region and its resources are used to good advantage by the Yawalapiti for most of their needs: buriti fibres for hammocks and baskets; sapé, a kind of thatch for the covering of the houses; taquara, a kind of bamboo for arrows, roots, and leaves as remedies, among other things. Salt traditionally used in the preparation of food is provided principally by the Mehinako, and derives from the cooking of the ashes of an aquatic plant. The large pans for preparing manioc come from the Mehinako and Wauja, who dominate the technology for their fabrication.

Manioc is planted by the men who cut down the forest, burn and clean the gardens. Gardens are individual property, belonging to the men, and are assumed as soon as a young man enters into seclusion (14-17 years). These property rights do not apply to the land as such, but only to the manioc plantation. The women pull up the roots, carry them, scrape them and squeeze out their poisonous juice. Manioc is basically consumed in the form of bread (beiju, ulári) " toasted flour, flatcakes, toasted in circular pans -, porridge made with beiju dissolved in water (uluni), and a porridge which is produced by boiling the poisonous juice (nukaya). The flour that remains at the bottom of the pans for squeezing, as well as part of the mass, is stored in silos in the center of the houses.

As for fish, cooking is done by both men and women; the processing of the manioc after it is planted, however, is entirely female work. The women are also in charge of fetching water for the village. It is they who spin cotton " also planted - , weave the hammocks and the mats for squeezing manioc, and prepare the urucum (red vegetal dye) paste, piquí oil and jenipapo dye, used in body ornaments. The men make the baskets, the cerimonial instruments (flutes and rattles), and take care of all the work in wood (benches, bows, mortars, scoops for turning over the beiju etc.). It is also the men who build the houses.

Sources of information

- CAVALCANTE, Ieda Maria da Silva. A presença dos meios de comunicação tecnológicos na aldeia Yawalapiti. Brasília : UnB, 1997. 107 p. (Dissertação de Mestrado)

- FERREIRA, Cláudio Santos. Intestinal parasites in iaualapiti indians from Xingu Park, Mato Grosso, Brazil. Memórias do Instituto Oswaldo Cruz, Rio de Janeiro : Fiocruz, v. 86, n. 4, p. 441-2, 1991.

- GODOY, Marília Gomes Ghizzi. Algumas considerações sobre as etnias e o problema de identidade indígena no Alto do Xingu : a aldeia Yawalapiti. São Paulo : USP, 1980. (Dissertação de Mestrado)

- MUJICA, Mitzila Isabel Ortega. Aspectos fonológicos e gramaticais da língua yawalapiti (aruak). Campinas : Unicamp, 1992. 92 p. (Dissertação de Mestrado)

- SÁ, Cristina. Observações sobre a habitação em três grupos indígenas brasileiros. In: NOVAES, Sylvia Caiuby (Org.). Habitações indígenas. São Paulo : Nobel ; Edusp, 1983. p. 103-46.

- VIVEIROS DE CASTRO, Eduardo. Alguns aspectos do pensamento Yawalapití (Alto Xingu) : classificações e transformações. In: OLIVEIRA FILHO, João Pacheco de (Org.). Sociedades indígenas e indigenismo no Brasil. Rio de Janeiro : Marco Zero ; UFRJ, 1987. p. 43-83.

. A construção do corpo na sociedade xinguana. In: OLIVEIRA FILHO, João Pacheco de (Org.). Sociedades indígenas e indigenismo no Brasil. Rio de Janeiro : Marco Zero ; UFRJ, 1987. p. 31-42.

. A inconstância da alma selvagem e outros ensaios de antropologia. São Paulo : Cosac & Naify, 2002. 552 p.

. Indivíduo e sociedade no Alto Xingu : Os Yawalapiti. Rio de Janeiro : UFRJ- Museu Nacional, 1977. 235 p. (Dissertação de Mestrado)

VIDEOS