Tapirapé

- Self-denomination

- Apyãwa

- Where they are How many

- MT, TO 917 (Siasi/Sesai, 2020)

- Linguistic family

- Tupi-Guarani

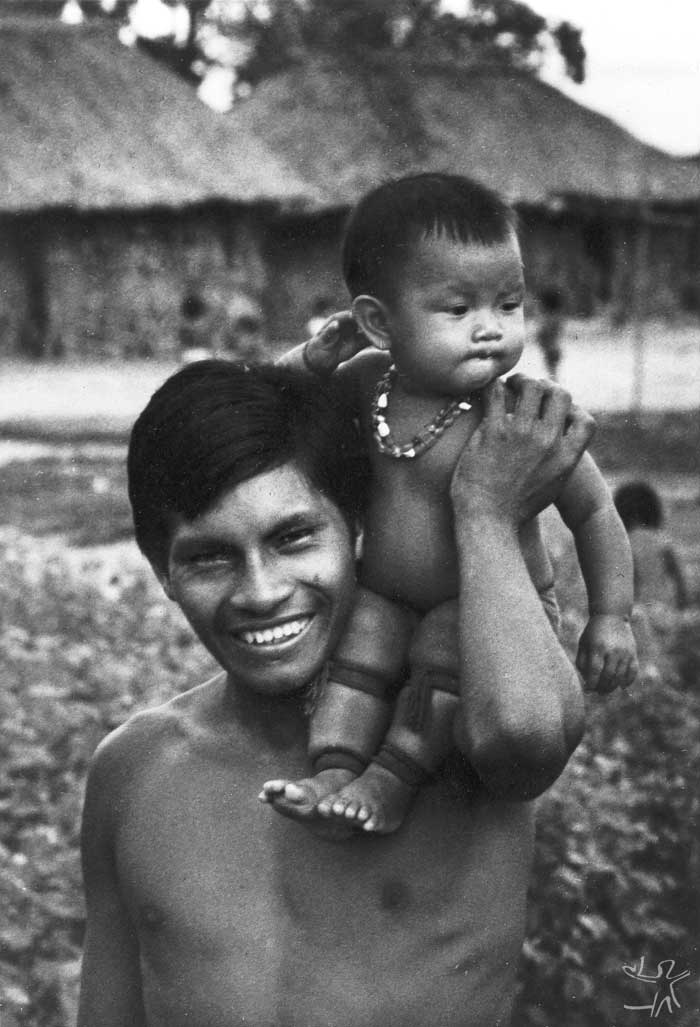

The Tapirapé are a Tupi-Guarani people who inhabit the region of the Urubu Branco mountain range in Mato Grosso. As a result of contact with the advancing development fronts from the mid- 20th century, they suffered an intense loss of population, and during this time they became close to the Karajá groups, formerly their enemies. After their traditional territory was occupied by cattle ranches, in the 1990s they managed to get official recognition of two indigenous areas, one of them in co-habitation with the Karajá. But in the Urubu Branco indigenous area they still face problems over land, because of invasions by farmers and prospectors.

Location and population

The Tapirapé live in a region of tropical forest, with typically Amazonian flora and fauna, divided by open fields and cerrado (low vegetation). Agriculturalists, traditionally their villages have been located near dense forests on non-flooding high ground, where they plant their crops. Tapi’itawa, the best known village of the group, has the ideal conditions for the location of a village: non-flooding land near high forests, but also near open fields next to the tributaries of the Araguaia and a perennial stream that does not run dry in the dry season. The Tapirapé exploit these environments according to the season and the activity: planting, hunting, collecting and fishing. At the moment they inhabit two indigenous areas, Tapirapé/Karajá, with 66.166 hectares, offically recognised in 1983, with a mixed population of Tapirapé and Karajá, and Urubu Branco, covering 167.533 hectares and offcially recognised in 1998.

History of occupation

The Tapirapé are an indígenous group who originally came from the lower stretches of the Tocantins and Xingu rivers, where they lived until the 17th century.They arrived in the riverside region of the middle Araguaia about the second half of the 18th century. Their presence was noted to the north of the Tapirapé river from the same period. (Baldus, 1970).

The Tapirapé's contact with their neighbours, the Karajá and the Kayapó, dates back to before the 17th century. Since then, they have oscillated between friendly co-existence to hostility and confrontation. The Tapirapé have a series of historical and mythological narratives about their centuries old presence in the woods on the left bank of the Araguaia, specifically in the mountainous region known as Urubu Branco, to the north of the Ilha do Bananal, mouth of the Javaé river, and in the mid-Araguaia.

The large displacements of indigenous groups in Brazil's central region which occurred up until the 19th century led them into contact with the Tapirapé in the forests of Pará, who then fled to the forest near the left bank of the lower Araguaia. In the history of the group, from the 18th century up until the present, we see the Tapirapé coming into contact with different Karajá groups whose territories they went around, as they approached the Ilha do Bananal, heading south: with the Karajá who lived in the Lower Araguaia, with the Javaé who lived in the interior of the island, and with the Karajá who lived in the mid-Araguaia and the mouth of the Tapirapé.

At the end of the 18th century and the beginning of the 19th, the Tapirapé found themselves divided. One part was on the left bank of the Araguaia, in the state of Pará, a little above today's border with Mato Grosso. Their villages already reached from Pará to the north and surroundings of the Tapirapé river in the 18th century. Another part of the group was living on the Ilha do Bananal (today in the state of Tocantins), in contact with the Javaé. They had already reached the northern point of the island in 1775 (Baldus, 1970). They maintained an intense communication with the Javaé, mainly the villages of Wariwari and Imotxi, with visits, regular trading, and exchanges of songs and rituals.

By 1900, the Tapirapé territory comprised the left bank of the Araguaia river until a little above the present division of the states of Mato Grosso and Pará. There were about 1500 people living in five villages, all located near the tributaries of the left bank of the Araguaia. The names of these villages were (from north to south): Anapatawa, Xexotawa (spelt “Chichutawa”), Moo’ytawa (“Moutawa”), Makotawa (“Mankutawa”), and Tapi’itawa (“Tampiitawa”) (Wagley, 1988: 49).

The Tapirapé, especially those in the northern villages, were repeatedly attacked by groups of Kayapó; to the east, they tried to keep away from the main course of the Araguaia, for fear of certain Karajá villages. Even so, in 1908 the German ethnographer Krause reported intense contact between the Tapirapé and Karajá groups in the village headed by Tapirapé chief João da Barra. He said these intermittent contacts oscillated between cordiality and hostility. (Krause, 1940-44, vol 70: 137-140 and Wagley, 1988: 52-53).

Among the Karajá groups, they maintained peaceful and later hostile relations in the 19th century with the Javaé. With the Karajá themselves their relations are more recent: since the mid-19th century up until the present. The northern Karajá especially, used to visit them during the dry season when the group met in the fields to the south of the Urubu Branco mountains. They were trading expeditions that often degenerated inot armed skirmishes, ambushes or bloody surprise attacks. Near a place called Tyha, on the edge of the Tapirapé river to the south of Urubu Branco, the Tapirapé can show two cemeteries of Karajá warriors who died in 1905 or 1910 during two big battles in the fields. The Karajá tried above all to steal the goods of the Tapirapé and carry off women and children. In fact many of the westerners who visited the northern Karajá at the end of the 19th century and beginning of the 20th registered the presence among them of captive Tapirapé women, young girls and children.

From the beginning of the 20th century the Tapirapé began to suffer ever more frequent attacks from the Kayapó, forcing them to abandon their northenr villages in the south of Pará and north of Mato Grosso, near the interior of today's Conceição do Araguaia and Vila Rica, and concentrate in those places near the hills, forests and fields of the mid-Tapirapé, in the state of Mato Grosso.

Today's Tapirapé call the place of these villages where they lived in the first three decades of 20th century Yrywo’ywawa, “the place where the Urubu Branco drinks”, or, as it is known in the region, “ the Urubu Branco serra (mountain)". This area consists of forests, hills and flat lands. The Urubu Branco range is located to the right of the Tapirapé range, and together, they continue the advance of the Roncador mountains in the direction of the Araguaia. From these villages, which had large fields of crops on the sides of the hills, they went on long hunting and collecting expeditions to the riverside fields along the Araguaia's tributaries, especially during the summer.

To the north of this region, near the Beleza river, was the Xexotawa village, one of the most northerly and the only one to remain inhabited until the end of the period. To the west and the south the limit of their territory was marked by the occupation of the Tapi’itawa, Tokynookwatawa and Xoatawa villages.

Today in the Tapirapé village there are about ten "mixed" couples, that is Tapirapé men married to Karajá women. Just one couple is formed of a Tapirapé woman and a Karajá man. These unions, which began in the 50s and 60s, were initially an answer to the need to repopulate the group. There was a big lack of women, especially, which led many young Tapirapé to marry and go to live with the parents of their Karajá wives. Like the Tapirapé, the Karajá are matrilocal. (on marriage,the son-in-law goes to live in his mother-in-law's house).

In an effort to escape from the alcoholism and political hegemony of the dominant family in the Karajá Itxala village, in 1990 just 5000 metres from the Tapirapé village of Tawyao, a new Karajá village called Tytema was formed by two extended families united by the marriage of their children. Many of these Karajá became evangelicals, partly in response to the problems they face because of alcoholism.

Today they inhabit two indigenous areas, the Tapirapé/Karajá, with 66.166 hectares, officially recognised in 1983, which contains Tapirapé and Karajá people, and Urubu Branco, covering 167.533 hectares, recognised in 1998.

History of contact

From 1910 until 1947 the inhabitants of Tapi’itawa, the biggest village in the group, received continual visits from officials of the old Indian Protection Service (SPI), rubber prospectors, Dominican and protestant missionaries, anthropologists and foreign and Brazilian travellers. This village, where the Tapirapé people had taken refuge in the period of intense depopulation, is one of the oldest and is the port of entry into Tapirapé territory.

At the end of the 1940s, a violent outbreak of malaria, influenza and the ordinary common cold led the population to collapse to less than one hundred people (Baldus, 1970). As the numbers fell, the survivors concentrated in the village of Tapi’itawa, seeking contact with the regional population and distance from the northern points of the territory, constantly under attack from the Kayapó.

In 1946 however the northerly village of Xexotawa was again occupied by a group of people led by Kamaira, an important family leader noted by Wagley (1988). He was accompanied by about two dozen people. This group decided to live in a village that was not so subject to contacts with outsiders and the diseases they brought with them.

In 1947 Tapi’itawa was violently attacked by the Kayapó Metyktire. The village was sacked and most of the houses, including the House of Men, were burned. Some people were killed, and the Tapirapé of Tapi’itawa dispersed through the region, seeking refúge in ranches and at the Indigenous Post of Heloísa Alberto Torres (now Tapirapé/Karajá), of the SPI.

Xexotawa was also attacked by the Kayapó. The precise date of the attack is unknown because they had no contact with the outside world. Carried out at night, it led the population to disperse and divide into two groups, isolated from each other, ignorant of each other's fate, believing the others were lost or dead. , One group went south, reoccupying the place of the Xoatawa village, while the others remained near the Xexotawa village, located around the higher reaches of the Crisóstomo river. Both groups remained completely isolated in the middle of the forest. They lost contact with the rest of the Tapirapé, with the outside world and with other indian groups for several decades until they were reunited with the other Tapirapé. The inhabitants of these two villages lived near the region which is now known as the Urubu Branco mountain range.

New expansion fronts

Although the occupation of the region by non-indians dates from the 1940s, it began to intensify in the 1950s, with Brazilians from other regions opening cattle ranches and speculating on land, encouraged by a government policy of fiscal incentives from official banks and agencies like Sudam, Banco da Amazônia and the Polomazônia programme. There were two basic aims: (1) to improve and enlarge the network of secondary roads to aid cattle ranching and (2) to develop and consolidate cattle ranching.

In 1954 the Real Estate Company of the Vale do Araguaia - CIVA- opened an office in the new village of Santa Teresinha. From the government of Mato Grosso the company obtained a concession for the purchase and sale of land titles covering large areas of Araguaia. After CIVA wnet bankrupt at the end of the 1950s, it was taken over by the Companhia Colonizadora Tapiraguaia, which continued to negociate plots of land inside the Karajá and Tapirapé indigenous areas.

All the territory immediately to the north of the Tapirapé river - including the Heloísa Alberto Torres Indigenous Post and the lands traditionally inhabited by the Tapirapé and the Karaj- were divided into plots and sold off to private buyers. The land of the villages in the Urubu Branco region were also divided up with the allegation that they were empty, unpopulated areas. The lands of Santa Teresinha, today the centre of the municipality with the same name, were also divided up and sold to ranchers who demanded that their traditional inhabitants shold be immediately removed.

Little Sisters of Jesus Mission

According to Wagley (1988), in 1950, Valentim Gomes, who was in charge of the SPI Post, helped by the Dominican missionáries, persuaded the scattered Tapirapé families to come together and form a village nearby. But the inhabitants of the Xoatawa village remained in the Urubu Branco area and the group which had remained in the Xexotawa region stayed near the headwaters of the Gameleira stream and to the north of that area, so the reunion was only partial. Thus the installation of the Tapirapé population in the new village, located about 80 kms from Tapi’tawa, near the bar of the river Tapirapé, was carried out by the SPI and was not an iniative of the indigenous group itself.

From 1951, at the request of the Dominican bishop of Conceição do Araguaia, the Mission of the Little Sisters of Jesus installed themselves in the village near the bar of the Tapirapé river, and began to provide healthcare for the indians. In the 1970s a lay couple from the Indigenist Pastoral team of the prelacy of São Félix do Araguaia began a literacy project in the Tapirapé language.

The arrival of the mission with their regular high quality assistance for the indians also saw the beginning of the recovery of the population, which had declined to 51 Tapirapé (Wagley, 1988) living in the new village, Tawyao, near the SPI post. But the inhabitants of Xoatawa and Xexoatawa remained without any healthcare and their populations were continually reduced by disease, the attacks of wild animals and hunger.

Once installed near the Karajá village at the bar of the Tapirapé, relations between the Karajá and Tapirapé groups improved and from 1949-50, they began an intense social and economic exchange.

In 1964 the first group of the remaining inhabitants of Xexotawa made contact with the population of Lago Grande, on the banks of the Araguaia. There were three women and two children. They had reached Lago Grande by slowly working their way along the Crisóstomo river and the region between the river and the Antonio Rosa stream. They belonged to a Tapirapé group which had remained isolated in the forest for 18 years. They were brought to live in the new village. In 1970 the last remaining group from Xexotawa accidentally met a local hunter, peaceful contact was established, and they were able to reencounter their ex-relatives who lived in the new village next to the post.

Companies and squatter farmers

In the 1970s and 80s there were violent clashes between large companies and squatter pioneers trying to occupy the region. Using armed militias and illegal harassment,the big agricultural companies forced the purchase, exit or simply expelled the small squatter farmers from the land they had occupied.

In the 1970s, during the military regime, the policy of the federal government, especially the Ministry of the Interior, to which Funai was subordinate, stressed the need to occupy the Amazon. Opposition to the legitimate territorial claims of the Tapirapé was centred in the persons of Coronel Nobre da Veiga, who was then head of Funai, and sargeant José Tempone, who was director of the Araguaia Indigenous Park. Supporting the Tapirapé during there tense negotiations with the federal government and Funai in 1980 were the prelacy of Sao Felix do Araguaia, the Catholic church and innumerable civil orgainsations in Brazil and abroad, who demanded that the federal government should obey the constitution. The "Tapirapé case" when the church and civil society allied themselves in defence of an emblematic example against an authoritarian state which was defying the law, became a paradigm for relations between indians and the state during this period.

The large farms, and successive companies, formed the basis of the occupation of the region, and the Tapirapé and the Karajá and other indian groups who were deprived of their lands by the illegal action of the Mato Grosso state are still today in conflict with them.

In the region around Urubu Branco, from the end of the 1980s right up until today, there have been a series of bloody conflicts involving rural workers and militias organised by local ranchers. In this region, considered one of the most explosive in the country in terms of land occupation, the ranchers and economic groups hire groups of gunmen to form armed militias and defend what they consider as their property.

Once the Tapirapé/Karajá indigenous area was recognised in 1983, the very next year the Tapirapé began to demand the recognition of their traditional land, in the region of Urubu Branco, which they had never ceased to occupy. From the 1950s to the 1980s it was first their place of habitation, and later a place for hunting, collecting and religious practices.

On 20th November 1993, tired of waiting for Funai to do something, 62 Tapirapé occupied the pastures of a ranch and reoccupied the Tapi’itawa village. In 1994 the head of Funai approved the report produced by a working group set up the year before to define the Urubu Branco indigenous area, along the lines of the Tapirapé proposal. In October 1996 Nelson Jobim, then Minister of Justice, signed Order No. 599 declaring that the area was in the permanent possession of the Tapirapé, and it was offically recognised later the same year.

Social organization

Tapirapé village consists of houses disposed in a circle around the House of Men, the takara. Up until the 1950s the houses were lived in by extended families. Ideally a Tapirapé family consisted of groups of related women (mother, daughters and granddaughters), representing three generations. However, today the extended family has given way to the nuclear family ( the couple and their children), which is now the norm. The nuclear family, as changes in the terminology of relationships show, is also the most stable kinship unit today.

Besides kinship, another important organisational principle of Tapirapé society are the so called "bird societies", or wyra. These societies, which are exclusively male, are divided into two big "halves", which in their turn are made up of age groups: older men, mature men and young men. A man is linked to his father's bird society and as he grows up he passes into the next age group in his half. The wyra compete as hunting groups, in ceremonial performances, singing, agricultural tasks, house building, etc.

Through the wyra the male population is divided into two halves, each then divided into three age groups. Wagley (1988) refers to these halves as the "white birds" and the "parrots" organised as below:

| White Birds | Age Group | Parrots |

| wrachinga | Jovens:10 – 16 anos | wrankura |

| wranchingió | Homens maduros: 16 – 35 anos | anancha |

| wranchingó | Homens mais velhos: 35-55 anos | tanawe |

Extracted from Wagley, 1988: 117 Another organising method of Tapirapé society is the "eating groups", tataopawa. As their name indicates, they meet to eat food and today have a basically ceremonial function. Up until the end of the 1940s, however, they operated as regulators, meeting to distribute and consume food (Wagley, 1977: 15). They act as intermediary groups between the village and the domestic household for the consumption of food (from the fields, from hunting, from collecting and fishing, etc). The "eating groups" provide links that unite people from different houses, forming one social unit. The transmission of membership in the "eating groups" passes from fathers to sons and mothers to daughters. Wagley mentions eight groups of tataopawa (here registered according to their original spelling).

| Tataopawa - "Eating Groups" - |

| Amirapé (the first) |

| Maniutawera (the manioc group) |

| Awaiku (the sweet manioc group) |

| Tawaupera (the village group) |

| Chakanepera (the cayman group) |

| Chanetawa (our village group) |

| Pananiwana (the river group) |

| Kawano (the wasp group) |

Extracted from Wagley, 1988: 128

The fundamental economic importance of the "bird societes"and the "eating groups" derives from their role in the production and consumption of food. Added to this is their importance in the ceremonial life of the group. Through a good humoured and ancient rivalry, the "bird societies" behave competitively. Ideally a Tapirapé village should have a big enough population to provide enough members for the "bird societies" and the "eating groups". Without these groups , neither economic activity nor ceremonial life would be able to operate (Wagley, 1988: 135). Inspite of the survival of communal forms of production, basically through the wyra, it is true to say that they have gradually assumed a more religious and ritual function.

Leadership

Politically Tapirapé society is extremely egalitarian. The leaders of the different houses in the village maintain daily contact, through the nightly meetings of the men in the yard of the takara. There they discuss all questions relating to the community. The main job of the "cacique" today is administering the community's goods, like the savings account, the outboard motor boat and the cattle. He also, in ther name of the community, establishes contact with third parties, whether indian or not. As formal chief he really just confirms decisions which have been exhaustively discussed by the collective group of men. Among the Tapirapé the figure of a strong leader, the "cacique" or "captain" who imposes his will on the others supported by his household, does not exist.

The present leaders are young individuals, between 30 and 40 years old, who speak Portuguese well, can read and write, and are surprisingly well informed about the national news which they accompany through the radio.

They achieved prominence during the process of confrontation with FUNAI and the ranches in the 1970s and 1980s. They are leaders who have been tested and approved by the community in the tir ng negociation process which guaranteed them the minimal land they needed to live on in Mato Grosso, avoiding their eviction to the Ilha do Bananal. Their profile contrasts with the old "caciques" , elderly men, who spoke little Portuguese and were illiterate, but who exercised their prestige in the rituals and had an excellent knowledge of traditional culture and history, and who were supported politically by their respective households.

Productive activities

The Tapirapé live in communities that depend mainly on agricultural activities. Their fields provide not only the basis of their subsistence, but also the structure, together with hunting, for their spiritual life.

The economic and religious activities take place in an appropriate place, non-floodable high forest. Only this ecosystem allows for the existence and operationality of the principles along which the village is organised: (1) kinship groups. (2) the bird societies - wyra and (3) the eating groups -Tataopawa. At least since the 19th century the Tapirapé have used territories which combine high forests, good for planting and hunting, close to areas along the banks of the Araguaia river, rich in fishing lakes, and near fields where seasonally they collect a large variety of wild species: nuts, honey and turtle eggs.

A village, according to the concept of the Tapirapé, should be located near their crops, so that village and gardens mix together. At certain times, like harvest time at the beginning of the year, the Tapirapé even go to live in shelters erected in the middle of their plantations, and the entire religious calendar of the group is linked to the ripening of the crops. The itinerant agriculture used by the Tapirapé up until the 1940s, when they had a vast territory at their disposal, has given way, today, to a more intensive use of the areas which are suitable for growing crops. Today it is common for them to plant new crops in old garden areas. Their agricultural activities include annual clearings to plant the new crops, which means that since the 1970s their gardens are located a long way from the village.

The abandoning of the traditional system and the exhaustion of the areas near the refuge to which they were transferred at the beginning of the 1950s led to a big fall in productivity. Today the species they grow most are: manioc for flour, corn, rice, banana, mamão, domesticated manioc, aipim, cará, batata doce, abóbora, amendoim, andu (a type of bean), cotton and other less important plants. Near their houses they grow urucum, mangos and cuité, used to make kari (a handmade bag which sells very well)

Traditionally, as their gardens got further away from the village, the Tapirapé moved it to be nearer to their crops. Wagley (1977) calculated that it took 20 years for the forest to regenerate so that the place could be inhabited again. Today, the living conditions to which they are subjected have forced the Tapirapé to abandon this rotativity of the village within a territory that is occupied in cycles. Today the gardens are often located 15 to 20 kms away from the village. This distance is too far for the Tapirapé, who have to walk it each day, carrying their produce on the return.

From an agricultural point of view, the potential of the Tapirapé/Karajá indigenous area is very limited and incompatible with an enimently agricultural people like the Tapirapé. Over 60% of their lands are low lying and annually flood. Another important part consists of pastures and sandy terrain, inappropriate for agriculture. The parts that are usable, to the north and northwest of the Tawyao village, are intensively worked.

The Tapirapé are giving more and more emphasis to "non traditional" activities, like the production of craftwork, fishing and cattle raising, to complement their subsistence. When they arrived in 1949 at the mouth of the river Tapirapé, a region rich in lakes full of fish, fish became a much more important part of their diet. Hunting, in comparison, became less important. However hunting provides the Tapirapé with an important alternative source of animal protein. Collective or individual hunts are regularly made, mainly during the height of the rainy season (February and March) near the Tawyao village and in the region of Urubu Branco. During this time game becomes almost the only animal protein available to the group.

Hunting

Besides its nutritional importance for the group, hunting has a fundamental symbolical importance. Hunting is sociologically important for the Tapirapé, because only the collective hunts allow the bird societies, the wyra, and the eating groups, the tataopawa, to act together. The ritual hunts are the start of the initiation ceremonies for the youths, their most important joint religious ceremony, by means of which they "produce" the new members of Tapirapé society.

The symbolic and religious importance attached to hunting means that the Tapirapé go annually to the Urubu Branco mountain. To do this they have to face the ill will and arrogance of the new occupants of the area who judge themselves with the right to stop them from entering a territory which they have frequented for centuries. Climbing over fences, avoiding roads and farmhouses, covering their tracks, the Tapirapé have to overcome all sorts of obstacles in order to be able to practice the rites that constitute their religion.

The species which are most sought by the Tapirapé due to their nutritional value are: wild boar (Dicotyles albirostris), peccary (Dicotyles tayassu), paca (Coelogenys paca), cotia (Dasyprocata, sp.), anteater(Myrmecophaga jubata), land turtle (Testudo tabulata), coati (Nasua narica), monkey (Cebus, sp), fresh water turtle (Podocnemis expansa) and turtle eggs, tracajá (Podecnemis unifilio) and their eggs, two sorts of deer (Dorcephalus bezoarticus) and (Mazama americana), armadillo (Euphrarctus sexintus), guariba (Alouatta, sp), tapir (Tapirus americanus) and duck (Alopochen discolor) among others.

The list is basically the same noted by Wagely (1988) and the only difference is that, due to the scarcity of meat today, most of the species which were banned because of food taboos, like certain species of deer and armadillo, now have their consumption allowed to the gender and age groups which up until the 1940s and 50s were not allowed to eat them.

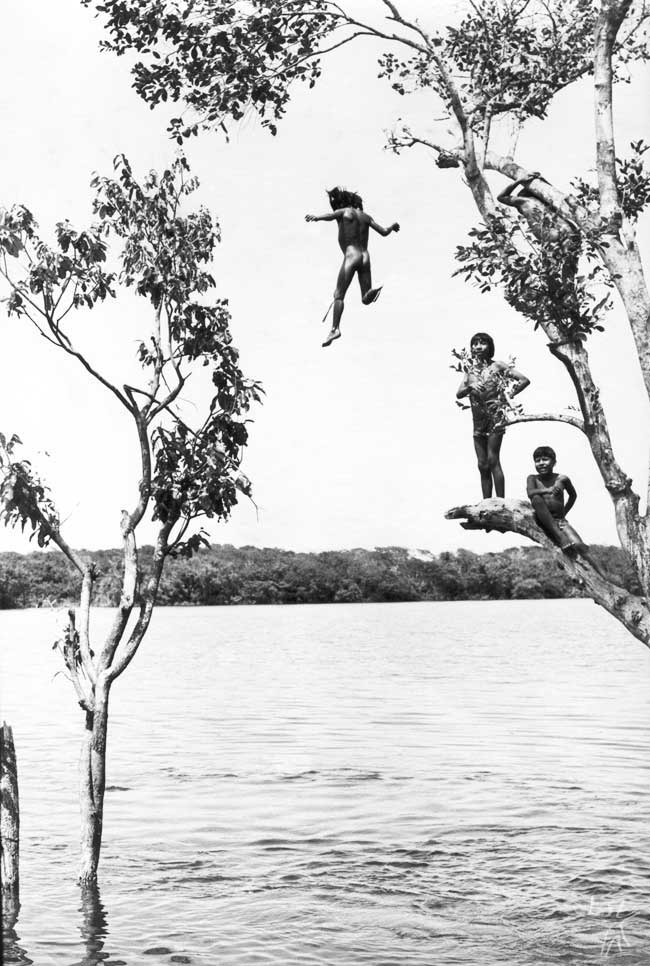

For the Tapirapé, hunting is not just of economicand religious importance. A forest people, it has an almost playful attraction for them. Unlike fishing, hunting thrills them. In December 1993, it was enough for someone to shout that they had seen wild boar in the trees nearby for the the men to rush off in mad pursuit, armed with rifles, bows and arrows and clubs. Hunting for the Tapirapé answers social, dietary and religious needs.

Collecting and fishing

Collecting

Collecting is done individually by families, who go on excursions during the summer through the open fields, also known as savannah, which during the winter are transformed into the wetlands typical of the Araguaia region. According to a survey carried out by students of the Tapirapé school in 1988, the group collect 47 types of wild fruit, especially the pequi. These provide an important source of food. The indians have a profound botanical knowledge of the region and they use species of vegetation which are vital to their subsistence. Besides the family collecting excursions to more distant regions, it is very common for women and children to go collecting in the savannah nearer to the village.

Collecting is combined with fishing, when the villagers go to the fields, camp beside the lakes and also look for turtle eggs on the beaches, and pick wild fruit, nuts and honey and explore the woods nearby. The collecting of honey for the ritual feasts is done by the wyra societies.

Fishing is always carried out during the summer in lakes, small streams and ditches, by means of traps, arrows where the waters are shallow, poisoning of the water with timbó or with nets and harpoons. these last two methods are used mainly when fishing the pirarucu. Fishing also takes place in the winter, although it is more difficult and less rewarding. There is also the "waiting" type of fishing, when the men build platforms in trees or on sticks near the riverbank and wait there to catch fish by shooting them with arrows.

Craftwork and cattle raising

Craftwork is now their most important and practically their only commercial activity, by means of which they raise money for buying other items which have become indispensable, like iron articles, clothes, guns and ammunition for hunting, salt, etc. Their craftwork consists mostly of basketwork, bows and arrows, paddles, spears, decorated gourds, clubs, feather adornments and the famous tawa, or "big face". In general they are articles of excellent quality in terms of their material, their making and finishing. They are sold to the trading boats and the tourists who visit the village in the summer. FUNAI's "Artindia" shop and several buyers from specialised indigenous craftwork shops in the south of Brazil regularly buy their products. These are then resold in cities like Goiania, Brasilia and Sao Paulo. Other buyers sell items, especially feather adornments, abroad, with a good profit margin. The Tapirapé also make their own trips to the south to sell their craftwork.

Cattle raising seems to have been an answer to the need to find new forms of subsistence within a limited space. The Tapirapé are, among the groups linked to the Araaguaia National Park, the only ones whose herd of cattle has shown continuous growth, by avoiding uncontrolled sales or slaughter. Their 200 head of cattle are looked after by Tapirapé cowhands, paid by the community. Although they know little about basic cattle raising., this was the solution they found to put an end to the problem of hiring local cowhands who then used to sell their cattle to breeders in Santa Teresinha.

Shamanism and ritual

The physical and emotional security of the Tapirapé depends on the power of their shamans. They believe that in order for a woman to have a child, the shaman must deliver the child’s soul to the mother. This is because, in anchunga, the supernatural world of the spirits , there is a finite number of spirits. The spirit, or soul, of the child enters the woman, invoked by the shaman (Wagley,1988:141). This means that a woman’s sterility or fertility is explained by the intervention of the shamans.

According to the Tapirapé, the main “reserve” of children’s souls, fundamental for the continuation of the group, is located exactly in the Urubu Branco mountain range, specifically in a big rock wall, from which , during the rainy season, a waterfall appears. It is called Yrywo'ywawa, (the place where the white vulture drinks water) . The mountain , home to the white vulture, took its name - Urubu Branco - from the bird.

Considered sacred by the Tapirapé, this place is also home to Tarepiri, a mythological personality who only appears to the shamans who seek him. Tarepiri is seen as the guardian of the Yrywo'ywawa and of Towajaawa ( also known as the Sao Joao mountain, another sacred place, also mentioned as the home of the white vulture). Tarepiri is considered to be the “father of the children from the place where the white vulture drinks”, or Yrywo'ywawa hakawa. Tarepiri defends this place against strangers, but welcomes the shamans.

To guarantee the continuity of births to the group the shamans need to travel in their dreams to Yrywo'ywawa and capture the souls of the children to introduce them into the wombs of the women. Another important guardian of Yrywo'ywawa is Karowara, thunder, who also keeps a large number of children’s souls.

The annual ceremonial cycles of the Tapirapé are composed of the following rituals : they begin with the xepaanogawa (at the end of September, beginning of Oc tober) followed by the building of the takara (December), then the ka’o , then the Marakayja (end of February, beginning of March) ending with the Tawa ritual (end of June).

The Marakayja is the biggest and most extensive ritual of the Tapirapé , the high point of the ceremonial cycles: the initiation of the boys and their passage to the category of men. Before the ceremony the Tapirapé go to the region of the Urubu Branco, and guided by their shamans , who they believe control the game, they remain there long enough to obtain the food that will be consumed during the Marakayja ceremony. The teams made up of the halves of the wyra, hunt especially the herds of wild boar, considered an excellent food, competing to see which of the halves will bag the largest amount.

In their dreams the shamans travel to the “house of the boar” located in the mountain called Towaiyawá (in Wagley’s spelling) or Towajaawa (in the current Tapirape spelling) where they maintain sexual relations with the female boars, to increase the size of the herds. The Marakayja ceremony is then held when enough meat has been obtained.

Note on sources

This text on the Tapirapé used as its source the Report on the Identification and Delimitation of the Urubu Branco indigenous area, organised by anthropologist André Amaral de Toral, and concluded in 1994. The purpose of this report was to provide a basis for the demarcation process of the Urubu Branco indigenous area, which was defined as being in the permanent possession of the Tapirapé in 1996.

Two important works had already been published on the Tapirapé. In 1970 Herbert Baldus published Tapirapé - Tupi tribe in Central Brasil. Baldus visited the Tapirapé in the 1930s and 40s, and produced a wide ranging ethnography with many documental and historical references, which is fundamental for the understanding of their culture.

Another fundamental reference for the study of the Tapirapé is the American anthropologist Charles Wagley, who published the book Welcome of Tears: the Tapirape indians of Central Brazil, in 1977. He accompanied the Tapirapé for 35 years, including a 15 month period with the group between the years 1939 and 1940.

Sources of information

- ALHO, Getúlio Geraldo R. Três Casas Indígenas : pesquisa arquitetônica sobre a casa em três grupos - Tukano, Tapirapé e Ramkokamekra. São Carlos : USP, 1985. 91 p. (Dissertação de Mestrado)

- BALDUS, Herbert. Os grupos de comer e os grupos de trabalho dos Tapirapé. In: --------. Ensaios de etnologia brasileira. São Paulo : Ed. Nacional ; Brasília : INL, 1979. p. 44-59. (Brasiliana, 101)

- --------. Tapirapé : tribo tupí no Brasil Central. São Paulo : Edusp ; Companhia Editôra Nacional, 1970. 512 p.

- HECK, Egon Dionísio; PREZIA, Benedito Antônio Genofre. Povos indígenas : terra e vida. São Paulo : Atual, 1999. 80 p. (Espaço e Debate)

- LEITE, Yonne. De homens, árvores e sapos : forma, espaço e tempo em Tapirapé. Mana, Rio de Janeiro : Museu Nacional, v. 4, n. 2, p. 85-104, out. 1998.

- PAULA, Eunice Dias de. Escola Tapirapé : processo de apropriação de educação escolar por uma sociedade tupi. Luciara : UEMT, 1997. 90 p. (Monografia de Graduação)

- --------. Fazendo as regras : a relação dos Tapirapé com a escrita. Rev. do Museu Antropológico, Goiânia : UFGO, v. 3/4, n. 1, p. 43-52, jan./dez.99/00.

- --------. Os Tapirapé e a escrita : indícios de uma relação singular. Goiânia : UFGO, 2001. 176 p. (Dissertação de Mestrado)

- --------; PAULA, Luiz Gouvêa de. Xema’eãwa, os jogos de barbante, e a escola Tapirapé. IN: SILVA, Aracy Lopes da; FERREIRA, Mariana Kawall Leal (Orgs.). Práticas pedagógicas na escola indígena. São Paulo : Global, 2001. p. 123-35. (Antropologia e Educação)

- PAULA, Luiz Gouvêa de. Mudanças de código em eventos de fala na língua Tapirapé durante interações entre crianças. Goiânia : UFGO, 2001. 205 p. (Dissertação de Mestrado)

- PRACA, Walkiria Neiva. Nomes como predicados na língua Tapirapé. Brasília : UnB, 1999. (Dissertação de Mestrado)

- O RENASCER do povo Tapirapé. São Paulo : Salesiana, 2002. 254 p.

- TORAL, André Amaral de. Laudo pericial antropológico relativo à Ação Ordinária de nº 91.0004263-3 (I-1.363/91) de desapropriação indireta na 4ª Vara da Justiça Federal do Mato Grosso. s.l. : s.ed., 1992. 120 p.

- --------. Os Tapirapé e sua área tradicional : Urubu Branco. In: RICARDO, Carlos Alberto (Ed.). Povos Indígenas no Brasil : 1991/1995. São Paulo : Instituto Socioambiental, 1996. p. 661-3.

- --------et al (Coords.). Xanetawa Parageta : histórias das nossas aldeias. São Paulo : Mari ; Brasília : Mec/Pnud, 1996. 112 p.

- WAGLEY, Charles. Cultural influences on population : a comparison of two tupí tribes. In: GROSS, Daniel R. (Ed.). Peoples and cultures of native South America : an anthropological reader. New York : The American Museum of Natural Story, 1973. p. 145-58.

- --------. Lágrimas de boas-vindas : os índios Tapirapé do Brasil Central. São Paulo : Edusp, 1988. 304 p. (Reconquista do Brasil, 2 série, 137)

- --------. Xamanismo Tapirapé. In: SCHADEN, Egon. Leituras de etnologia brasileira. São Paulo : Companhia Editora Nacional, 1976. p. 236-67.