Apiaká

- Self-denomination

- Where they are How many

- MT, PA 1050 (Siasi/Sesai, 2020)

- Linguistic family

- Tupi-Guarani

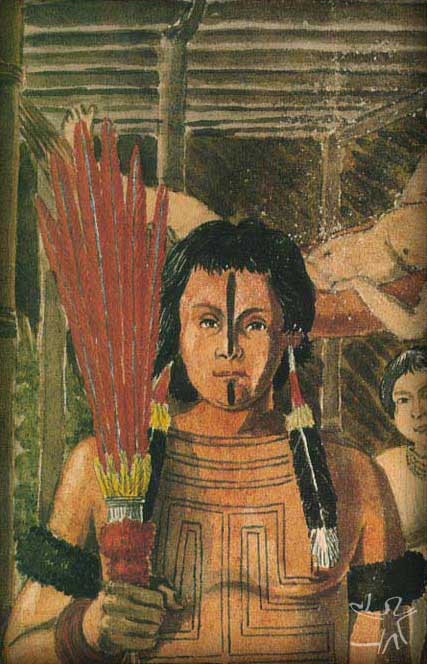

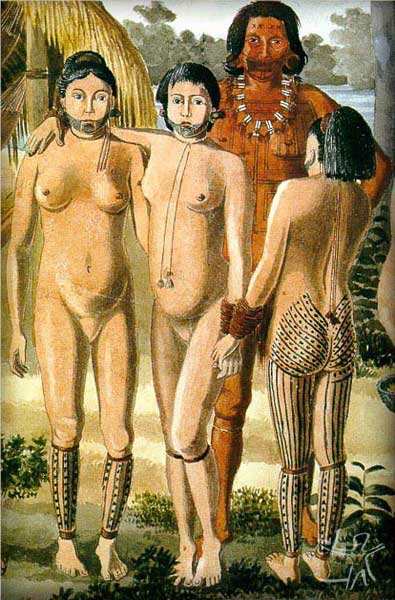

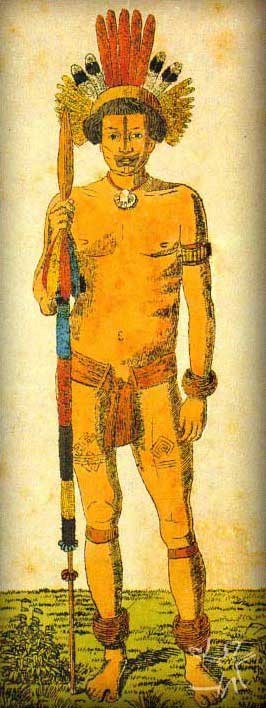

The Apiaká were a populous and warlike people when the rubber economy reached the southern portion of Amazonia in the mid 19th century. After sporadic conflicts with these colonizers, the Apiaká became their allies, though they continued their revenge warfare against neighbouring indigenous peoples throughout the 19th century (learn more in the chapter Contact history). The elaborate material culture and beautiful body decoration of the Apiaká impressed Hercules Florence, draughtsman on the Langsdorff Expedition, who visited Apiaká villages on the Arinos and Juruena rivers in 1828 and produced important textual and visual records of the people.

Suggestively, official registration of the toponymy of northern Mato Grosso at the start of the 20th century consecrated the traditional occupation of the Apiaká people, giving their name to an upland region, two rivers and a municipality.

In the mid 20th century the Apiaká were declared extinct by two important ethnologists, Darcy Ribeiro and Curt Nimuendaju. However the Apiaká, despite the long and intense coexistence with the Kaiabi and the Munduruku, they never ceased to see themselves and be seen as a distinct people. In spite of the massacres, epidemics, missionization and government abandonment, the Apiaká resisted as a collective and developed a complex interpretation of the past that guided their political struggle for a more just future.

Also read the Apiaká entry edited by the anthropologist Eugênio Gervásio Wenzel and published on the Indigenous Peoples in Brazil site in 1999

Name

According to E. Wenzel, the word Apiaká is a variant of the Tupi word apiaba, meaning ‘person,’ ‘people,’ ‘man.’ However, the Apiaká leaders explain that their people’s name refers to a wasp that when attacked travels long distances to exact revenge on the aggressor with an extremely painful sting: “We are very easy going, but if you mess with us, we strike back, just like the Apiaká wasp.” The meaning chosen to represent that attitude of the people today indicates that the warrior inclination remains latent, although diplomacy has been the strategy adopted in dealings with non-Indians and neighbouring indigenous peoples.

The Kaiabi call the Apiaká tapy’ ysing, ‘light-skinned people,’ a term that may refer to both the colour of their skin and to the mythic event that separated the peoples. The Kaiabi of the Rio dos Peixes tell that in the past the Apiaká and Kaiabi formed a single people until the former stopped painting themselves with annatto and constituted a distinct group. For their part, the Apiaká vehemently reject any prior identification with the Kaiabi.

Language

The Apiaká language belongs to the sixth branch of the Tupi-Guarani family along with Kaiabi, Juma, Parintintin and Tupi-Kawahib (Rodrigues 2002). The linguist Aryon Rodrigues (1984/85) produced a reconstruction of Proto-Tupi-Guarani in which he points out that contemporary languages from the Tupi-Guarani family are distinct manifestations of what was once the same language, which also explains the cultural similarities found even today among various Tupi-Guarani peoples.

[Editor's note: In 2011 the last known speaker of Apiaká language passed away.]

All the Apiaká speak Portuguese and those married to Munduruku and Kaiabi speak their spouse’s language fluently or at least are capable of understanding it perfectly. Although the Munduruku and Kaiabi idioms are spoken on a day-to-day basis in the Apiaká villages, especially as a vehicle for disparaging remarks, they are limited to the domestic spaces and informal conversations. The language used in formal conversations is Portuguese. Hence although they cannot impose their own language on the co-resident Munduruku and Kaiabi, the Apiaká at least manage to impede the languages of these peoples from becoming the official languages in their villages. In this context, Portuguese functions as an instrument of resistance employed by the Apiaká to prevent their cultural absorption by the Munduruku and Kaiabi.

Despite the linguistic proximity, the Apiaká do not allow Kaiabi to be taught in their villages’ schools; on the other hand, they readily permit Munduruku teachers to give lessons in their language, a linguistic preference that stems from historically constituted sociopolitical relations. For years the Apiaká have been attempting to revive their language through the school but have so far been unsuccessful; a recent initiative towards this aim was the production of a ‘Apiaká Word’ textbook.

Location

The traditional territory of the Apiaká comprises the middle and lower courses of the Arinos and Juruena rivers, including their principal eastern affluents in Mato Grosso state and western affluents in Amazonas state. It also includes the lower course of the Teles Pires and its eastern affluents in the state of Pará and western affluents in Mato Grosso, where most of the people headed at the start of the 20th century, fleeing from the violence of the tax collectors in Barra de São Manoel (a town situated on the left shore of the Tapajós, soon after the confluence of the Juruena and Teles Pires, which today falls under the jurisdiction of the state of Amazonas). The Juruena and Teles Pires are the main tributaries of the Tapajós; on its lower course they drain a still preserved region of Amazonian forest and demarcate Mato Grosso’s border with Amazonas and Pará, respectively.

The Apiaká conceive of this area, locally called the Pontal do Mato Grosso or Pontal dos Apiacás, as an environmental and social unit.

The relocations of the Apiaká were prompted by the expansion of various extractivist economies towards the region, especially, though not exclusively, rubber extraction. In the 21st century, having recovered demographically and becoming stronger politically, the Apiaká began to demand official recognition of a portion of this traditional territory from which they had been expelled.

Today there are seven Apiaká villages in the states of Mato Grosso and Pará: Mayrob and Figueirinha, both located on the right shore of the Rio dos Peixes (Apiaká-Kayabi Indigenous Land, MT); Mairowy, located on the left shore of the Teles Pires (Kayabi Indigenous Land, MT); Bom Futuro and Vista Alegre, both located on the right shore of the Teles Pires (in the Munduruku Indigenous Land, PA); Minhocuçu, situated on the right shore of the Teles Pires (Kayabi Indigenous Land, PA); and Pontal, located on the right shore of the Juruena, in the area now in a process of identification by FUNAI (MT). In addition, on the lower course of the Juruena and Teles Pires a number of sections of Apiaká extended families live in separate houses, maintaining kinship ties and political and economic cooperation with the residents of the Pontal and Mairowy villages.

There are hundreds of Apiaká living in Munduruku villages (Missão Cururu, Posto Teles Pires and Sapezal), a Kaiabi village (Tatuí) and in towns and cities in the north of Mato Grosso (principally Porto dos Gaúchos and Juara), Pará (especially Jacareacanga, Pimental, Itaituba, Santarém and Belém) and Amazonas (principally Barra de São Manoel and Apuí). The Apiaká also speak of the existence of a group of isolated kin in the Pontal do Mato Grosso, a region of dense forest in the far northwest of the state.

Demography

The seven Apiaká villages mentioned previously are home to about 450 Apiaká, generally married to Munduruku and northeasterners (descendents of the ‘rubber soldiers’) and to a lesser extent to Kaiabi. There are also a few hundred Apiaká living in Munduruku and Kaiabi villages and in towns and cities in northern Mato Grosso, Pará and Amazonas. Given the large-scale geographic dispersion of the Apiaká and the complexity of their identificatory dynamic, it is impossible to present a precise figure for their total population, only the estimate of 1,000 people.

Due to the traumatic nature of contact and the dramatic demographic losses, the older Apiaká shun talking about the past; moreover, the custom is for people not to speak of the dead, factors that explain the fragmentary genealogical knowledge of the younger Apiaká. Apiaká leaders say: “Had our people not dispersed in this way, today we would number more than five thousand.” Here ‘dispersing’ means abandoning the traditional Apiaká way of life and marrying unknown people – this is the form in which the Apiaká express the social disintegration inflicted on their people. As they conceive of culture as a reversible process (and no as an immutable condition), the Apiaká who live in villages believe that their village-less kin – children, grandchildren, siblings, cousins, aunts and uncles, and nieces and nephews – can very easily return to live as Apiaká if they so wish.

The information on the Apiaká population in the colonial period oscillates between 2,700 (Gomes Jardim 1847) and 16,000 (Machado de Oliveira 1898). In 1895, the traveller Henri Coudreau (n.d.) encountered approximately 100 Apiaká Indians living in five villages on the lower Juruena.

The Apiaká experienced a demographic decline at the turn of the 20th century, a period when the previously friendly relations established with non-Indians deteriorated. In 1902 the office of the Mato Grosso Tax Collection Service was opened in Barra de São Manoel, located within the area disputed with the Pará government. Each of the first four collectors from Mato Grosso successively declared war on the Apiaká, going as far as to decimate an entire village at the São Florêncio waterfall on the lower Juruena (Rondon 1915).

In 1912, Captain Costa Pinheiro, a member of the Rondon Commission, encountered 32 Apiaká refugees at the tax office; they were the survivors of the massacres perpetrated by the collectors and were considered the last of the Apiaká, though they were definitively not, as will be seen in later sections.

Contact history

Since the 18th century texts have been produced that express the viewpoint of the travellers, missionaries and colonizers concerning the encounter with indigenous peoples of the Tapajós river basin, which allows us, nonetheless, to glimpse the context in which these encounters took place, thereby providing important clues through which we can understand Apiaká historical action.

The area between the Madeira and Tapajós rivers had been recorded with a high indigenous population density since the 17th century, inhabited by numerous Tupi-speaking peoples and some highly mobile Macro-Ge peoples who formed an intricate network of relations maintained through warfare and exchange (Menéndez 1981/82 and 1992). Possibly these peoples did not form discrete, long-lasting social units, with villages instead comprising a formless set of neighbouring local groups not subject to a common authority and lacking any clear boundaries, unlike the 16th century Tupinambá (Fausto 1992).

The first explorers of the Tapajós valley recorded the predominance of the Tupinambá and Tapajós, expansionist and warlike peoples who practiced intertribal trade and the enslavement and subordination of smaller groups, but who quickly succumbed to contact with non-Indians, ceasing to be mentioned by the chroniclers after 1690. Menéndez writes that “the space left by these two groups quickly became occupied by those who had been subjected or enslaved and the emergence of new groupings is recorded,” with the Mura, Sateré-Mawé and Munduruku “seeming to have comprised for a long time a kind of protective shield” for the peoples who occupied the more deep-lying areas of the Tapajós-Madeira region (Menéndez 1989 and 1992).

In the 18th century the information on these diverse non-hegemonic peoples, produced by religious figures, government employees and travellers, was primarily concerned with fixing names and localizations, contributing to form a static and fragmented image of a region characterized by intense movement and by loosely interconnected social units. The Apiaká comprised one of the most forest-dwelling non-hegemonic peoples; the range of their territory was determined by warfare expeditions and by the search for stones for their axes and bamboo to make arrows. They trekked through these vast tracts of forest in pursuit of their traditional enemies, the Matanawi, Tapayuna, Munduruku and Nambikwara, displaying a considerable capacity for mobilizing for warfare.

The well-known facial tattoos, a distinctive feature of the Apiaká people, depicted by Hercules Florence during the expedition led by Baron Langsdorff, testified to the “feats and acts of bravery in combat with enemies,” as well as participation in the anthropophagic rites arising from warfare (Castelnau 2000; Guimarães 1865; Nimuendaju 1963). At the end of the 18th century a movement of Apiaká territorial expansion began, which provoked a geopolitical rearrangement in the region of the middle and lower Arinos (Menéndez 1981).

The earliest information about the Apiaká dates from 1746, provided by João de Souza Azevedo, who during the first official navigation of the Tapajós river from Mato Grosso mentions a ‘realm of the Apiacás’ on the lower Arinos (cited in Fonseca 1880). That year diamond deposits had been discovered in the province of Mato Grosso; the news prompted numerous ‘entradas’ and ‘bandeiras’ (Indian-raiding and prospecting expeditions) which set out from São Paulo. The headwater region of the Arinos river came to prominence two years later in 1748 when gold and diamond mines were discovered, including the famous Santa Isabel mines. Lieutenant-Colonel Ricardo Franco de Almeida Serra reported that, sadly, the hostility of the Apiaká had been one of the determining factors in the decline of the mines in question (Almeida Serra 1797).

In the first half of the 19th century the Jesuit canon José Guimarães (1865) and the traveller Francis de Castelnau (2000) provided detailed information on the Apiaká way of life. The first spent some days in the company of a delegation that had journeyed to Cuiabá to present themselves to the governor; the second met some Apiaká in Diamantino. Both emphasized that the Apiaká maintained friendly relations with the Brazilians while engaging in warfare with neighbouring indigenous peoples.

Revenge warfare, headhunting and anthropophagic rites formed a Tupi cultural matrix in the region of the sources of the Tapajós river. These practices, which so whetted the curiosity of the Europeans, were probably abandoned in the second half of the 19th century. At this time, the indigenous peoples in the north of the Province, established along the Arinos-Juruena-Tapajós river system, became important to the governments of Mato Grosso and Pará (the São Manoel river, later baptized the Teles Pires, would only be explored in the 20th century), since they occupied a region containing abundant natural resources, targeted by private entrepreneurs from São Paulo and the provincial governments of Mato Grosso and Pará. This meant the need to forge alliances with those indigenous groups who proved amenable.

However at the end of the 19th century, after the trade route between Cuiabá and Belém had become firmly established, a new problem emerged for the central government: the need to populate and organize the extraction of resources from a region considered distant and inhospitable. The indigenous groups had already provided proof that they would not become the most productive workers; hence the plan was to bring poor Europeans to Amazonia to work in agriculture and extractivism. At that moment the Apiaká ceased to be treated as allies useful to the Empire and began to be treated as an obstacle to capitalist expansion and the ‘development’ of the nation.

It was in this context, aggravated by territorial and fiscal disputes between two states (Mato Grosso and Pará), that the Apiaká started to be systematically persecuted by government employees. From the indigenous viewpoint, the turn of the 20th century corresponds to the moment when the Apiaká definitively abandoned their revenge warfare and began to become dependent on industrialized objects, with the exception of a portion of the group who returned to the forest, rejecting the life-style of the non-Indians (and who today are presumed to live in the Pontal region).

The Apiaká narrative on the origin of the contemporary way of life concentrates on the figures of Paulo Corrêa, a powerful ‘boss,’ and his wife, an Apiaká woman who despised her own kin. Paulo Corrêa committed so many abuses in the Barra de São Manoel region that one of his right-hand men killed him and delivered his head to the Apiaká, declaring: “Here’s your brother-in-law’s head; he killed a load of your kin, now you can him to your village.” The Apiaká then took the head to Apiakatuba village (on the shores of the São Tomé river, an eastern affluent of the Juruena) and held a beautiful festival – the last of its kind. The Apiaká explain that Paulo Corrêa was a brother-in-law who acted like a jaguar: instead of behaving like a relative, respecting them and sharing his objects and food, “he turned into an animal” and went to the extreme of killing his own people.

After this ‘war’ in Barra, the Apiaká became victims of epidemics and were spatially dispersed, taken by rubber bosses to exploit native rubber areas, scattered across the territory; others withdrew deeper into the forest, in the region of the São Tomé river. In the first half of the 20th century the Apiaká who accepted contact with non-Indians married Munduruku, Kaiabi, Kokama and Sateré-Mawé spouses and migrants from northeastern Brazil, called arigós or ‘rubber soldiers;’ they abandoned the villages on the shores of the smaller rivers and began to live near to the Franciscan Mission on the Cururu (PA) and in the ‘colocações’ (worker settlements) run by rubber bosses on the lower course of the Juruena and Teles Pires rivers.

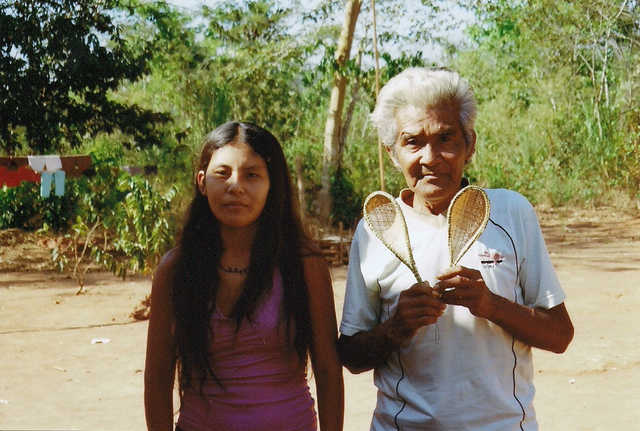

In the 1960s, sections of extended Apiaká families who still worked in rubber extraction on the lower course of the Juruena river moved at the invitation of the Jesuit missionary João Dornstauder of the Anchieta Mission, to Tatuí village, established to convert the Kaiabi, on the Rio dos Peixes (an eastern affluent of the Arinos). In the 1970s these Apiaká established contact with their kin living in the region of the Cururu river, many of whom subsequently moved to the Rio dos Peixes, bringing with them a number of Munduruku, who married with them. Since then the Apiaká have been reorganizing themselves politically and fighting for respect of the rights guaranteed to them by the new indigenist legislation.

Although the Apiaká have chosen the diplomatic route in their relations with non-Indians, it is worth noting that the need for enemies remains alive, primarily expressed in the hostile relation maintained with the Kaiabi. It could also be said that the rivalries of the past explain the fact that the Apiaká have not been fully incorporated by the Munduruku or the Kaiabi. As mentioned in an earlier section, when they went to live alongside the Kaiabi, the Apiaká did not marry people from the latter group, preferring to ‘import’ Munduruku spouses from the Cururu Mission, and still less adopt the Kaiabi language. On the other hand, the Apiaká married to Munduruku, living in Munduruku villages and speaking the language, are generally identified by the Munduruku as Apiaká, even though the relationship is friendly.

We cannot, therefore, comprehend the current situation of the Apiaká without considering their insertion in the regional social network in place before the arrival of the colonizers and maintained even today through trade exchanges, political support, matrimonial alliances and warfare. This network, which undoubtedly changed over the centuries and seems to have enabled the survival of the Apiaká, today manifests as a web of unstable and tense political, commercial and matrimonial relations. Significantly, today the Apiaká act as pivots of this network, connecting the Kaiabi and Munduruku in the interaction with non-Indians and their institutions. The main continuity seems to reside, then, in the need to exchange with the outside in order for the Apiaká to reproduce as a collectivity, a recurrent them in more recent research on Tupian peoples.

Sociopolitical organization

The community

The Apiaká proudly assert that today they live ‘in a community’ (a term generally employed as a synonym of village), a form of social and political organization that emerged in the second half of the 20th century, distinct from both the communal houses (malocas) of the 19th century and the small, continually relocating groups of isolated kin that they claim exist in the Pontal region. Community designates a number of extended families linked by kinship, political and economic relations, who occupy and use the same territory and recognize the political authority of the leader, including too the ‘ribeirinhos,’ who are kin and compadres (godparents to each other’s children) who live in separate houses along the river shores and frequent the village.

In the community the most important social principle is reciprocity: the logic of the gift subordinates commercial relations, constitutes ties within the extended family and furnishes the parameters of political prestige. The Apiaká undertake a process of quotidian familiarization of the co-residents, especially through food sharing, meaning that the Kaiabi, Munduruku and descendents of arigós (northeastern migrants) who live in their villages share the sense of community.

The Apiaká community is organized such that the extended families are linked by a pubic sphere, materialized in the hall, a space of political sociality that finds parallels among various Tupi-Guarani peoples. The Apiaká hall is an area used for formal conversations (especially, though not exclusively, between men) and festivals in which prestige and distinction can be obtained, where internal conflicts are mediated and where alliances are forged with the other Apiaká villages, with the neighbouring Munduruku and Kaiabi villages and with non-Indians.

Domestic sociality, on the other hand, identified with the houses, is defined both by the psychological and physical security provided by near kin and by gossip and witchcraft accusations, modalities of private talk that can have crucial political effects, expressing centrifugal social forces. Each domain corresponds to an idiom, that is: kinship is the idiom of relations in the community, while ethnicity is the dominant idiom in the political arena outside the village.

A ‘good’ community is one in which the moral principles of generosity, peacefulness and hospitality are observed and where there is a school, health post, hall, soccer pitch, pasture, oven house and community swiddens, road or landing strip and material goods for collective use (such as a speedboats, outboard motor, a large metal pan to toast manioc flour, vans, chainsaw, TV set and satellite dish, cattle and so on). People say that the Apiaká villages are well-kept, cheerful and tranquil. Commensality during festivals and cooperation during the construction of these collective spaces, beginning with clearing of the forest where the village will be sited, form the bases of community solidarity.

Territoriality

Contemporary Apaiká villages are situated on terra firme (off the floodplains), generally next to a curve in the river and close to backwaters where they can fish and streams providing fresh water for day-to-day use. There is always a strategic high point ensuring a good view of the river: “From here we can always see who is arriving before they see us,” they say. The area initially cleared in the forest to build the village is small with the Apiaká preferring the more fertile terra preta (black soil) sites, a choice that requires detailed knowledge of large expanses of territory. The site of a former Apiaká village continues to be visited for years, even after the departure of its residents; so much so that the Apiaká of the Rio dos Peixes and the Teles Pires never ceased to trek through the lower Juruena region to gather, hunt and fish. Even today they travel there in search of Brazil nut trees, copaiba trees, babassu palm thatch, medicinal plants, wild fruits, and the diverse species of fish and animal game that exist only in the region.

The village and its surrounding area comprise the only space conceived as properly social and adequate for humans. As the physical product of the continuous work of domesticating the environment performed by the co-residents, the village is opposed to the depths of the river and the forest, places that contain many mysteries and dangers for people and home to monstrous beings. This explains older men’s insistence on children and women not leaving the boundary of the village on their own, and the desire to possess guard dogs to protect the houses.

The subaquatic world is conceived as a replica of the human world with swiddens and houses; the dreaded enchanted beings who live there, namely the ‘water mother’ (in Apiaká: ajáng), the anaconda (mosahúa, female owner of the fish) and the river dolphins (piraputóa) sometimes try to seduce humans: when they manage to capture a person’s ‘shadow’ (ang, a synonym of spirit and soul), his or her body may waste away fatally. The victim of these beings becomes apathetic, may present fever, loss of appetite, nightmares and deliriums and refuse to live with co-residents. In this case a healer is called on to make incantations and shake black physicnut leaves over the sick person’s body.

The forest is home to the siruría, an anthropomorphic being that bewilders the hunter, making him lose his bearings; the boa constrictor and a type of vine (garlic vine) also disorientate the man, making him walk in circles and lose his path; the juruparí monkey, which attacks at night, beheading the victim and sucking his blood; the ‘capelobo’ (or ‘mapinguari’), a stinking being that causes death to humans; the peccary bands that, if challenged in an appropriate way by the hunter, can capture his spirit with cries and laughter, an affliction that must be cured through medicinal baths with forest plants. Sirurekanjíga, the owner, leader and spirit of the animals species, does not represent a danger to humans, as such, but cannot be shot at under any circumstances. To ensure the abundance of game, men typically placate him by leaving a cigar in the hollow of a tree trunk. As can be noted, the relation with the ‘owner of animals’ is defined as a kind of respectful camaraderie: it is possible to convince him with presents to release a reasonable amount of game for them to hunt and kill.

Economic activities

The organization of economic and leisure activities is based on the alternation of two main units of time: ‘summer’ or the dry season and ‘winter’ or the rainy season. In the Amazonian ecosystem the variation in river levels can reach as much as 10 metres, altering the aspect of the villages considerably. Summer is the period with the most abundant supply of food, when various tubers and other vegetables are harvested, river turtles are caught and their eggs collected from the beaches. People also gather assai, moriche, bacaba, patauá and other fruits to make ‘wines’ (juices); the rivers are filled with fish and the forest with game, as well as various types of larvae and fungi.

Most of the festive banquets take place in the summer. The winter is ‘sad’ because it is difficult to leave to hunt and the swiddens are not yet producing crops, though it is possible to gather various kinds of wild fruit. November is the time to catch leafcutter ants whose metasoma is eaten mixed with manioc flour; between December and February is the period for ‘breaking’ Brazil nuts and travelling to the city to buy industrialized goods.

The Apiaká swiddens are a cause of great pride for their owners, with agricultural produce, especially tubers, comprising the base of their diet. The size of the swiddens varies according to the number of members of the conjugal family and the man’s disposition for the work given he is the one responsible for felling the area. The swiddens are distributed arbitrarily in the territory surrounding the village in accordance with the desire of each conjugal family, and are located at a distance varying between 10 and 40 minutes walk from the houses. All the village territory is collectively owned. There is no private ownership of land: what exists is the right of each conjugal family to use it for an indeterminate period – a right obtained through effective cultivation.

The Apiaká practice slash-burn agriculture in which the vegetation is felled, cleared and burnt in the dry season (especially August) and planting is undertaken during the first rains, usually in September. The fallow system is used where section of the deforested area is left to rest while the other section is used for cultivation, which intensifies the fertility of the soil. Thus a family may simultaneously possess three or more swiddens in different stages: one lying fallow, another producing and a third or fourth recently planted.

They are excellent agriculturists and their swiddens are large and diversified: they plant pineapple, pumpkin, peanuts, banana, sweet potato, cashew, sugarcane, yam, beans, ingá, papaya, bitter and sweet manioc, arrowleaf, passion fruit, watermelon, maize and cucumber. In the house yards there are usually fruit trees (especially tucum palm and maripa palm) and beds with plants used for food and medicinal purposes.

Along with agriculture, fishing, hunting and gathering are – in this order – the main subsistence activities in the villages. Use of the various fishing techniques depends on the season of the year: in winter when the river is full the men fish in backwaters from moored canoes, making use of rod, line and hooks and the bait preferred by the target fish; at night they use the ‘espinhel,’ a trap made from nylon fishing line and bait; during the day, they make an ‘esperinha’ (trap) from the same materials. In the summer they head to the waterfalls to catch large fish with harpoons or bows and arrows; they make excursions to lakes to ‘beat’ timbó fish poison, made from a vine that removes oxygen from the water; they set ‘tapagens’ (traps) in creeks; on moonlit nights they leave to ‘zagaiar’ (fish with a small spear). Yellow-spotted river turtles are caught with hook and line or with a harpoon. Today the Apiaká hunt with guns but they also use bows and arrows; they frequently depart in small groups at night to ‘fazer espera,’ that is, wait for prey in the tree canopies. Men gather palm fruits by climbing the trees with the help of a strip of embira fibre, cutting down the ripe bunches with a machete.

‘Indian food’ or ‘true food,’ consumed day-to-day, comprises a sophisticated cuisine involving various types of very well-cooked fish or meat. Meat is eaten roasted, as a broth, as a porridge (mujica) or barbecued, wrapped in wild banana leaf, a form known regionally as ‘pupecado,’ and is invariably accompanied by manioc flour. Though fish is the everyday food, game is considered the Indian food par excellence. After three days of meals based on fish, it is common to hear people say: “We’ve no food, the men need to go hunting.” The most prized quality of meat is its fat; the hunters shun very lean prey since they consider the absence of fat a signal of illness. Game meat must circulate within the extended family and is not traded; when the men bring large quantities of game or fish, the food is distributed to the entire community and may lead to feasts in the hall.

The Apiaká also eat wild and cultivated foods, either raw or in the form of wines (assai, bacaba, moriche, muruci, patauá and uxi), accompanied by manioc flour; manioc cake, bread and tapioca; tubers and vegetables, either cooked or made into non-fermented drink; ‘chicha’ (fermented drink) made from manioc and maize; honey; wild mushrooms; palmhearts; palm grubs; wasp larvae; the metasoma (posterior section) of the leafcutter ant. The favourite meals, more rarely consumed by the Apiaká, true delicacies that distinguish their ‘culture’ from that of non-Indians and other indigenous peoples (principally the Kaiabi, Munduruku and Kayapó) are monkey meat cooked with Brazil nut milk and river turtle roasted in the shell. The Apiaká are selective in their diet; of the approximately 170 known species of birds, they eat just over 10; of the roughly 60 known mammal species, they consume approximately 20 and of the almost 100 known species of fish, they eat more or less 50.

They make most of the objects used day-to-day, such as slings (plant and loom), wicker baskets and sieves, paddles, canoes, clubs, necklaces, ear decorations and bracelets made from seeds and beads. They build their houses with clay and raw materials found in the forest (babassu thatch for the roof and wood for the main structure). In the past Apiaká material culture was important in the region of the headwaters of the Tapajós; Robert Murphy (1960) states that the Munduruku adopted the tree bark canoes from the Apiaká and George Grünberg (2004) relates that the Kaiabi appropriated the anthropomorphic design (‘tanga’) of the sieves made by them.

Kinship relations

Marriage

Marriage marks the entry of young people into adult life and redefines the relations between the parents of both spouses, who begin to treat each other with a certain deference. The couple are expected to become an economic and political cell with some degree of independence from their respective parents, though the cooperation and solidarity that exists between them never ceases completely.

The place of residence of a young couple is one of the most sensitive decisions in Apiaká social life. Co-residence is not just important from the viewpoint of kinship relations, but also from political and economic viewpoints. In principle, a recently married man should move to the house of his parents-in-law and provide ‘bride-service’ for about a year; after the birth of the first children he should build a house for the new conjugal family, ideally neighbouring that of his parents-in-law.

In the Apiaká villages the conjugal families are residential units interconnected in extended families; the latter comprise the main unit of production and consumption within which food, industrialized objects and artefacts circulate in the form of gifts. The extended family is a basic political unit in the village: reciprocity between these units takes place through a network of economic transactions, political connections and kinship ties (including godparenting) which at a virtual level includes all the co-residents, albeit in different degrees. The village split directly affects the extended family, which moves practically en bloc when there is any kind of serious conflict. The tendency towards autonomization of extended families is a trait shared by other Tupian peoples. From the Apiaká point of view, all the community members are kin (though not all of them are so to the same degree and intensity). This is an indication that residence is the main structural factor in this social organization.

A common ascendant is the person of reference around which family relations are organized. Each group of extended families or kingroup is identified with the place where it lived for the longest time. Consequently the Morimã are associated with the Rio dos Peixes; the Kamassori with the Anipiri river and the lower Tapajós; and the Paleci with the Anipiri and the middle Teles Pires.

Differently to other Tupi-Guarani peoples, the Apiaká do not express a preference for marrying a cross-cousin (for men, the father’s sister’s daughter or the mother’s brother’s daughter), although it is possible to observe many marriages between first, second and third degree cousins. In their own words, they prefer to marry a ‘distant kinsperson’ (that is, a distant consanguine, for a man: the mother’s sister’s daughter’s daughter, the father’s father’s brother’s daughter’s daughter, the father’s mother’s sister’s daughter’s daughter, and the father’s father’s brother’s daughter’s son’s daughter). It is not possible to identify prescriptive marriage rules; there merely exists the prohibition on marrying ‘close kin’ (that is, an immediate consanguine, for a man: maternal and paternal grandmothers, mother, mother’s sister, father’s sister, sister, sister’s daughter, brother’s daughter, daughter and granddaughter). People also marry appropriately – albeit increasingly less desirably – to Kaiabi and Munduruku from neighbouring villages and to regional non-Indians known for a long time.

Marriage is inexorably associated with locality since each new union consolidates or creates new political and economic alliances, intensifying the kinship ties within the village and within the regional social network.

Over the course of the 20th century the Apiaká entered into interethnic marriages in the rubber extraction areas (seringais), though notably always preferring to marry long-term ‘neighbours,’ known for some time, irrespective of the ethnic group, although all the indigenous peoples belonged to the Tupi trunk. Over the last decade, however, they have decided to restrict marriages to people in the villages classified as Apiaká, in detriment to the Kaiabi and Munduruku from neighbouring villages. This decision forms part of the wider project for revitalizing Apiaká culture, which includes recovery of the indigenous language and aspects of their material culture and the fight for official recognition of part of their traditional territory. As part of this political project, there has been an intensification of visits exchanged between the villages of the lower Teles Pires and Juruena and those of the Rio dos Peixes. These visits have resulted in various marriages classified as exclusively Apiaká.

In the 1970s, when the Apiaká were living in a mission village on the Rio dos Peixes, marriage between cross-cousins may have been a possibility, an option that proved important during the period when they were reorganizing as a people alongside the Kaiabi and the Jesuit missionaries living in the area. In the 1990s, by now demographically, socially and politically stronger and heavily missionized, the Apiaká opted to marry at a greater distance, preferring distant consanguines.

In Mayrob, a populous village, young people around the age of 14 find suitable spouses without leaving the village and only need to move house. In Mairowy village, on the other hand, young men and women around this age have problems in finding a spouse since almost everyone is a ‘legitimate cousin’ and unmarriable. As a result, young people have to turn to non-Indians from the region or the Munduruku of the upper Tapajós willing to move to their village, or pursue a career as a ‘lover’ (someone who only has casual affairs), which is frowned upon by the older generation. These non-Indians and the Munduruku are not, however, completely unknown; they are very often kin or distant consanguines of one of the parents of the Apiaká spouse. Although desirable, marriages between young people from Mayrob and Mairowy pose a drawback for the young man, who must move to the village of his parents-in-law to carry out his bride-service (following the uxorilocal pattern of residence); given the distance separating the two villages, it is very difficult for him to visit his parents frequently, and thus the move tends to be definitive.

Godparenting

Ever since they were contacted by missionaries at the start of the 20th century, the Apiaká adopted an important strategy in terms of amplifying their kinship ties: godparenting. This relationship is given official sanction in the Catholic ritual of baptism, which results in a couple accepting certain obligations in relation to the godchild. Currently on the Rio dos Peixes the priest who carries out the baptisms is a Jesuit who has lived in the village for more than twenty years. On the lower Teles Pires, people turn to the Franciscan priests from the Cururu Mission. The godparents are expected to give presents to the child on birthdays and at Christmas, to give day-to-day advice and to raise the child if the parents die. Baptism is conceived as a kind of spiritual protection of the child. The Apiaká say that baptized children become sick less and have more chances of surviving than those who have not yet been baptized.

However the Apiaká emphasize the horizontal bond between the godparents than the vertical bond between godparents and godchild valued by the church. For the Apiaká, godparenting basically comprises the bond established between two couples (previously united by consanguinity, affinity or friendship) through the mediation of a child. The four adults thereby interconnected start to call each other publicly ‘compadre’ and ‘comadre,’ vocatives that imply a degree of reverence, and exhort the godchild to ‘take the blessing’ to his or her godparents whenever they meet. Godparents are obliged to show hospitality, mutual aid and unlimited generosity in terms of food and objects in general.

Godparenting consecrates pre-established relations of kinship and solidarity and represents a way of expanding the kingroup and, therefore, a couple’s network of relations beyond the extended family, which in turn intensifies the political and economic cohesion of the village and between neighbouring villages, as well as strengthen political and economic alliances with non-Indians. Godparenting is a form of conceiving co-residence at the level of kinship insofar as it establishes a ritual affiliation (vertical connection) combined with a kind of ritual affinity (horizontal connection).

In this sense, godparenting is a kind of reduced model of affinity with concrete impacts only on the triad of parents-godchild-godparents. It is relatively common for couples to ‘swap godchildren’ (a couple baptizes the child of the couple who had baptized their child), meaning that these two godchildren ‘become like siblings’ and, if they are of opposite sexes, cannot marry. However there is no sanction on marriage between the siblings of the respective godchildren; in other words, the ban on marriage is not elastic and does not extend beyond the people directly involved.

Birth and reclusion

The consolidation of the conjugal family occurs with the birth of children and is based both on the daily sharing of food and on the practice of reclusion after birth. In the weeks prior to the birth, women belonging to the wealthier families will have already collected embroidered nappies, clothes, beads to make necklaces and bracelets, a basin for the infant’s first baths and an aluminium dish. Birth is not surrounded by any great mystery. Any women who has had a number of children can perform the role of midwife and the child’s father can watch the event. Normal birth takes place inside the couple’s house, which the father, mother and newborn should not leave for at least a week after birth. The placenta must be buried in a safe place where there is no risk of it being found by domesticated animals; if, for example, a dog digs up the placenta, the baby will sicken; when the birth takes place in hospital the placenta is simply discarded.

Immediately after the birth, the mother and child should be bathed with lukewarm water inside the house. “A woman in reclusion is a delicate thing,” she cannot carry anything heavy, become upset, here strange noises or ‘startle.’ During reclusion the mother may only eat a few kinds of birds, as well as select fish: piau (apart from the head, “if she eats the head the child’s teeth will be broken”), aracu, pacuzinho – in other words, fish with small scales and that contain little blood; she can also eat porridge, rice, pasta, fermented manioc flour (though dry flour is more appropriate), milk and coffee. Some ‘white foods’ help the woman to put up with the period of reclusion since they are not classified as taboos. The food restrictions in general condense an analogical symbolism.

Fish with fatty flesh, such as piranha, filhote, pintado, barbado, jandiá, mandubé, jaú and matrinxã – large carnivorous fish with a lot of blood – are highly dangerous, along with other animals and birds such as turtles, tapir, deer, trumpeters, curassows and various species of monkey: “This goes into the milk, the child feeds and becomes ill.” As well as the damaging effect on the child’s body, there also negative effects for its ‘soul’: “The tapir take’s the child’s spirit; today the tapir is here in the forest, then he goes to the water, dives in, crosses the river, climbs the river bank, goes into the forest again and heads off; the child’s spirit cannot keep up with the animal and the child becomes ill.” Fatty kinds of meat only cause harm to people during critical moments of the life cycle; under normal conditions, they are the preferred food.

For a month the father cannot bind or twist any object, especially babassu thatch, which is ‘fatty,’ or else the child will suffer from ‘espremedeira’ (colic); he cannot fish with hooks (the emphasis is on the movement involved in catching the fish), shoot with bows or guns, chop with an axe, use an outboard motor, weave cargo baskets, hammer nails or seal canoes. Cedar is also ‘dangerous’ “it’s bitter with a strong smell, you can’t touch it.” “The father can only go out with his friends, go for a walk, but without becoming involved in anything.” If the newborn is a boy, the restrictions on the father must be even more strictly observed. If the child’s navel is injured, any action from the parents can worsen its state. The restrictions on food and activities are gradually relaxed over the course of the child’s first year until they are lifted completely.

Reclusion also takes place during menstruation and when a close relative is sick or dies.

Concept of the person

From an Apiaká perspective, a full person is someone capable of acting in accordance with the parameters established for each age and gender.

Small children are given special care since they are extremely vulnerable to the actions of people and supernatural entities. The child become seen as a true person after he or she starts to walk and speak. The separation between genders gradually increases and reaches its peak after the age of ten, when the adults begin to speculate on potential spouses for their children. Normally a boy of fourteen and a girl of twelve are physically and socially capable of forming a relatively autonomous social unit since they have already acquired the basic techniques and knowledge for life in the village; everything they need to know has been learnt from a young age through direct but gradual observation and participation in adult activities and topics. Older people are not expected to contribute intensely to productive activities, though many are happy to do so.

There is no rigid gender dichotomy; instead there are activities associated with women (looking after the house and children, cultivating swiddens and gardens, preparing and distributing food, making items from seeds and beads, slings, and so on) and activities associated with men (preparing the swidden terrain, obtaining food through hunting, fishing and gathering, making canoes and wicker baskets, fabrication of headdresses, spears, harpoons, bows and arrows, interaction with outsiders, formal politics and so on) carried out in a relation of complementarity.

The interdependence between genders is manifested in all spheres of social life, including:

- in the socialization of children, where the mother looks after their day-to-day needs while the father provides them with animal-based foods and industrial items, especially clothing;

- in production, where the man is basically responsible for obtaining food from outside the village (in rivers, the forest and the city), while the woman is responsible for transforming these into food within the household: everything men capture, kill or gather in activities combining a mixture of danger and adventure, the woman domesticate, ‘treat’ or alter;

- in material culture, where men fabricate tools from plant material (baskets, cargo baskets, shoulder baskets, sieves, etc.) for the women, while the latter make adornments (necklaces, bracelets and rings – though not headdresses) for the men;

- in the political organization of the community, which allocates positions in pairs, that is, the post of ‘cacique’ (male leader) is paired with that of the ‘cacica’ (female leader) and the post of ‘vice-cacique’ with that of ‘vice-cacica,’ although ‘politics’ is conceived as a male activity;

- in cosmology, since a menstruating or pregnant woman can provoke ‘panema’ (in Apiaká: ipareún) in her husband if she touches the game he killed, or his gun, fishing rod, bow or arrow. Panema is a widespread concept in Amazonia and involves a state of general dejection in the man and bad luck in hunting and fishing trips.

Interaction with ‘other’ beings (animals, spirits, non-Indians) and extra-domestic spaces is a male prerogative. Men are responsible for felling the area of forest to be used as a swidden, gathering wild fruits and honey, toasting flour, providing the house with game, fish and industrial goods. Women plant seeds, cultivate (the swidden and vegetable patches), carry (firewood, wild fruits, swidden produce), raise (children, pets and xerimbabos, ‘wild pets’), harvest (although men help their wives, care of the swidden is the woman’s responsibility), sieve (flour, the wild fruits used to make wines), clean (the house, yard and swidden), cook (for daily meals and feasts in the hall), and process Brazil nuts intended for sale.

In the Apiaká language ang signifies ‘soul,’ ‘spirit’ or ‘shadow.’ A healthy person is someone whose soul is closely attached to the body. The Apiaká believe that for various reasons the soul can become disconnected from the body, provoking serious problems in the body (diseases), which can lead to death. From their point of view, people are responsible for their own sickness and for that of others, meaning that a person can make the soul of another separate from his or her body.

Thus a person can become ‘desmentida’ (that is, clumsiness, aches and fever, a state in which the soul can separate from the body) as a result of an immoderate action, such as climbing a tree that is too tall. In this case, the person turns to a ‘puller’ from the village who gives him or her massages with creams made from animal fat. ‘Desmentido’ is an affliction that deeply concerns the Apiaká, covered in a supernatural aura. On the other hand, a man who throws stones in the river when he catches sight of a river dolphin can be attacked by the animal and sicken (his soul separates from the body and begins to live in the subaquatic world); in this case he must turn to a healer who uses chants and a bundle of leaves shaken over his body, or prescribes baths with infusions from particular wild plants.

The Apiaká value self-restraint and are wary of people who are out of control. They explain that anyone, man or woman, can transform into an ‘animal’ (a synonym for spirit), needing only remove their human ‘clothing’ since the reverse of every person is animal, such that in the animal state the head is where the rear is usually found, and vice-versa. However only those initiated into shamanism and motivated by malignant intentions can metamorphose in a controlled way, which reveals the phenomenon of a shaman-less shamanism since the Apiaká claim that they have been without this type of specialist for a long time.

Despite denying the existence of Apiaká shamans, shamanic beliefs and the seeking out of shamans from other ethnic groups remain alive. Moreover they claim that their isolated kin in the São Tomé region possess powerful shamans who guide them during their journeys. They also explain that the leaders of the past were also shamans, but “being a shaman is not good, the shaman does not see things as we do: the yam for him is maize, potatoes are rats, shit is a jaguar.”

The stories of people temporarily transforming into animals are an idiom of sorcery accusations, part of a flux of veiled hostility and violence – elements that are not completely suppressed by the ethics of generosity and pacificism preached by influential people in the Apiaká villages. A person who turns into an animal is called a ‘bad shaman’ or ‘sorcerer’ (paséa is the term designating both sorcerer and good shaman in Apiaká) and acts always at night. This is not a theme about which the Apiaká like to talk, a fact that makes evident an emphasis on the moral and pragmatic aspects of knowledge: “knowing how to talk about,” knowing, always implies a know-how evaluated according to strict moral parameters.

The accounts of “people who turn into animals” expresses the instability of the human condition for the Apiaká. The belief in temporary transformations for malignant purposes is a way of claiming that humanity is acquired when the animal potion of the person is tamed and, reciprocally, of claiming that negatively exceeding the limits of sociality is also a way of ceasing to be human. The persistence of this symbolism, which finds echoes among other Tupi-Guarani peoples, even after decades of territorial dispersion, social disruption and missionization, is a rare expression of social resilience.

Notes on the sources

Compared with other indigenous peoples, the material available on the Apiaká is fairly rich, but a deeper analysis of the records relating to the Apiaká remains to be produced. The watercolours (published in Monteiro & Kaz 1988, see the preface by B. Komissarov) and the diary by Florence (1941) provide precious information on the social life of this people at the start of the 19th century. Various issues of the Revista do Instituto Histórico e Geográfico Brasileiro contain important papers exclusively about the Apiaká in the 19th century and other texts that allow us to grasp something about their relations with the colonizers. The Central Library of the University of Brasilia and the library of the Unicamp Institute of Philosophy and Human Sciences hold a complete collection of the periodical.

Georg Grünberg’s thesis (2004) on the Kaiabi, recently published by the Instituto Socioambiental, contains some information on the relations between this people and the Apiaká and includes a useful regional historical survey covering the 19th and 20th centuries.

An excellent regional ethnohistorical reconstruction by Menéndez was published in História dos Índios no Brasil (Carneiro da Cunha 1992), although the corresponding map is available only in a later publication, namely the Revista do Museu Paulista (Menéndez 1981/82).

The reports by Rondon (1915 and 1916) and the article by Farabee (1917) can be found at USP’s Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology.

A copy of the book by Barbosa Rodrigues (1875) is found in the rare works section of the Central Library of the University of Brasilia, and a copy of the original version of Coudreau’s book (n.d.) in the rare works section of UNICAMP’s Central Library. The two books provide a rich panorama of the region of the headwaters of the Tapajós in the second half of the 19th century. The archive of the Indian Museum in Rio de Janeiro holds thousands of microfilms on the Kaiabi and the Munduruku in which new information on the Apiaká in the 20th century will undoubtedly be found. There is also a text from 1902 written by Koch-Grünberg in German entitled “Die Apiaká-Indianer (Tapajós, Mato Grosso),” published in Verhandlungen der Berliner Gesellschaft fur Anthropolothro Ethnologie und Urgeschichte, Berlin, vol. 34.

The dissertation by Wenzel (1986) contains information on Apiaká cuisine and provides bibliographic references that allow us to reconstruct the history of the people from the mid 18th century. As of present, the doctoral thesis by Tempesta (2009) is the most detailed work on the Apiaká people, focusing on their conception of history and the contemporary sociopolitical organization.

Sources of information

- ALMEIDA Serra, Ricardo Franco de. (1797) 1865. “Extracto da descripção geographica da provincia de Mato Grosso”. In: Revista Trimensal do Instituto Histórico e Geográfico Tomo 6. Rio de Janeiro.

- ____________. (1779) 1869. “Navegação do rio Tapajóz para o Pará”. In: Revista do Instituto Histórico e Geográfico Brasileiro IX. Rio de Janeiro.

- ARNAUD, Expedito. 1971. “A ação indigenista no sul do Pará”. In: Boletim Museu Emílio Goeldi. Nova Série: Antropologia, no. 49, Belém.

- CASTELNAU, Francis de. 2000. Expedição às regiões centrais da América do Sul. Belo Horizonte/Rio de Janeiro: Editora Itatiaia.

- CASTRO, Miguel João de & FRANÇA, Antônio Thomé de. 1868. “Abertura de Communicação Commercial entre o districto de Cuyabá e a cidade do Pará por meio da navegação dos rios Arinos e Tapajós, emprehendida em setembro de 1812 e realisada em 1813". In: Revista Trimensal do Instituto Histórico e Geográfico Tomo XXXI, 1a. parte. Rio de Janeiro.

- CHANDLESS, William. 1862. “Notes on the rivers Arinos, Juruena and Tapajós”. In: Journal of the Royal Geographical Society. London, XXXII.

- COUDREAU, Henri. (1897) s. d. Viagem ao Tapajós. Brasiliana, Biblioteca Pedagógica Brasileira, Cia. Editora Nacional.

- FARABEE, William Curtis. 1917. “The Amazon Expedition. The Tapajos”. In: The Museum Journal 8 (2). Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania.

- FLORENCE, Hercules. 1941. Viagem Fluvial do Tietê ao Amazonas de 1825 a 1829. Edições Melhoramentos.

- FONSECA, João Severiano da. 1880. Viagem ao Redor do Brasil, 1875-1878. Rio de Janeiro: Typographia de Pinheiro & C. Vol. 1.

- GOMES JARDIM, Ricardo José. 1847. “Creação da Directoria dos Indios da Província de Mato Grosso”. In: Revista do Instituto Histórico e Geográfico 9. Rio de Janeiro.

- GrÜnberg, Georg. 2004. Os Kaiabi do Brasil Central. História e etnografia. Instituto Socioambiental.

- GUIMARÃES, José da Silva. (1844) 1865. “Memórias sobre os usos, costumes e linguagem dos Apiaccás, e descobrimento de novas minas na Provincia de Mato Grosso”. In: Revista Trimensal de História e Geografia, Jornal do Instituto Histórico e Geográfico Brasileiro, vol. 6. Rio de Janeiro.

- KIETZMAN, Dale. 1967. “Indians and Culture Areas of Twentieth Century Brazil”. In: HOPPER, Janice (ed.) Indians of Brazil in the Twentieth Century. Washington: Institut for Cross-Cultural Research.

- MACHADO DE OLIVEIRA, J. J. 1898. “Memória da nova navegação do rio Arinos até a Villa de Santarém, estado do Grão-Pará”. Revista Trimensal de História e Geografia. Jornal do Instituto Histórico e Geográfico Brasileiro. IHGB, vol. 19. Rio de Janeiro.

- MALCHER, José Maria da Gama. 1964. “Índios. Grau de integração na comunidade nacional”. In: CNPI. Publicação no. 1.

- MENÉNDEZ, Miguel. 1981/82. “Uma contribuição para a etno-história da área Tapajós-Madeira”. In: Revista do Museu Paulista, vol. XXVIII, USP.

- _______________ 1992. “A área Madeira-Tapajós. Situação de contato e relações entre colonizador e indígenas”. In: Carneiro da Cunha, M. (org.) História dos Índios no Brasil. São Paulo: Cia. Das Letras.

- MONTEIRO, Salvador & KAZ, Leonel (eds.) 1988. Expedição Langsdorff ao Brasil, 1821-1829. Livroarte Editora Ltda. 3 vols. Textos de Boris Komissarov.

- NIMUENDAJU, Curt. (1948) 1963. “The Cayabi, Tapanyuna and Apiacá”. In: STEWARD, J. (ed.) Handbook of South American Indians. Vol. 3: The Tropical Forest Tribes. Washington: Smithsonian Institution, Bureau of American Ethnology.

- OLIVEIRA, João Batista de. 1905. “Relatório do estado de catachese e civilização dos índios de Matto Grosso, apresentado ao Presidente da Província em data de 31 de Dezembro de 1858”. In: O Archivo- Revista destinada a vulgarisação de documentos geographicos e históricos do Estado de Matto Grosso, Ano 1, vol. III, Cuyabá.

- PADUA, Alexandre Jorge. 2007. “Contribuição para a fonologia da língua Apiaká (Tupí-Guaraní)”. Dissertação de Mestrado, Instituto de Letras/UnB.

- ___________ & TEMPESTA, Giovana (orgs.). Palavra Apiaká

- PIMENTA BUENO, José Antônio. (1837) 1916. “Extracto do discurso do presidente da Província do Mato Grosso”. In: Revista do Instituto Histórico e Geográfico Brasileiro II, 3a. ed.. Rio de Janeiro.

- PRUDÊNCIO, João Batista. 1904. “Informações ministradas ao Presidente da Província de Mato Grosso, Augusto Leverger,... sobre o município de Alto Paragucuy Diamantino”. In: O Archivo - Revista destinada a vulgarisação de documentos geographicos e históricos do Estado de Matto Grosso, Ano 1, vol. I, Cuyabá.

- PYRINEUS DE SOUSA, Antonio. 1916. “Relatório de exploração do rio Paranatinga e seu levantamento topográfico bem como dos rios São Manoel e Teles Pires.” In: Commissão de Linhas Telegraphicas Estrategicas de Matto-Grosso ao Amazonas. Publicação no. 34, Anexo 2. Rio de Janeiro: Typographia Leuzinger.

- Ribeiro, Darcy. 2002. Os índios e a civilização: a integração das populações indígenas no Brasil Moderno. Petrópolis: Vozes, 3a edição.

- Rodrigues, Aryon Dall’Igna. 1984/85. “Relações internas na família linguística tupi-guarani”. In: Revista de Antropologia vols. 27/28.

- ______________________ & Cabral, Ana Suelly Câmara (orgs.). 2002. “Revendo a classificação interna da família Tupí-Guaraní”. In: Línguas indígenas do Brasil: fonologia, gramática e história. Atas do I Encontro Internacional do Grupo de Trabalho de Línguas Indígenas da ANPOLL, Tomo I. Belém: EDUFPA.

- RONDON, Cândido Mariano da Silva. 1915. “Relatório apresentado à Directoria Geral dos Telegraphos e à Divisão de Engenharia (G 5) do Departamento de Guerra”. In: Commissão de Linhas Telegraphicas Estrategicas de Matto-Grosso ao Amazonas. Publicação no. 26, Anexos 1, 2 e 3, vol. 3. Rio de Janeiro: Typographia Leuzinger.

- __________. 1916. “Conferências realizadas nos dias 5, 7 e 9 de outubro de 1915 pelo Cel. Candido Mariano da Silva Rondon no Teatro Phenix do Rio de Janeiro sobre trabalhos da Expedição Roosevelt e da Commissão Telegraphica”. Commissão de Linhas Telegraphicas Estrategicas de Matto-Grosso ao Amazonas. Publicação no. 42. Rio de Janeiro: Typographia Leuzinger.

- Serviço de Proteção aos Índios (SPI). Inspetoria Regional 6 (Cuiabá). Relatórios Microfilmados dos Postos Indígenas José Bezerra e Pedro Dantas, disponíveis no Museu do Índio/Funai.

- TEMPESTA, Giovana Acácia. 2009. “Travessia de Banzeiros. Historicidade e Organização Sociopolítica Apiaká”. DAn/UnB . Tese de Doutorado.

- TOCANTINS, Antonio Manoel Gonçalves. 1877. “Estudos sobre a tribu “Mundurucú”. In: Revista Trimensal do Instituto Geográfico e Ethnographico do Brasil. Tomo XL, 2a. parte. Rio de Janeiro.

- Wenzel, Eugênio. 1986. “Em torno da panela Apiaká”. FFLCH/USP. Dissertação de mestrado.