Akuntsu

- Self-denomination

- Where they are How many

- Linguistic family

The last six survivors of the people known to outsiders as the ‘Akuntsu’ live in two small malocas set close to one another in the forests of the Omerê river, an affluent of the left bank of the Corumbiara in the southeast of Rondônia state. The area comprises a small reserve of forest previously belonging to a private farm interdicted by Funai at the end of the 1980s. The region comprises terra firme equatorial forest with quite a few small hills and a few springs. Like the other forest reserves of Rondônia, the territory is seriously under threat from crop farming and cattle ranching.

Name

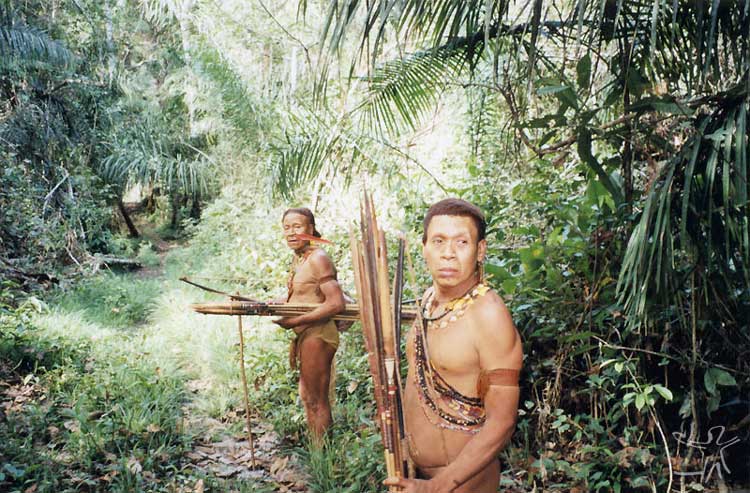

![Kunibu [foreground] in front of the maloca. Photo: Adelino de Lucena Mendes, 2002.[b] Kunibu [foreground] in front of the maloca. Photo: Adelino de Lucena Mendes, 2002.[b]](http://img.socioambiental.org/d/208030-11/akuntsu_1.jpg)

Information concerning the name Akunt'su, Akunsu or Akuntsu in the ethnographic literature is practically non-existent, at least prior to official contact with Funai in 1995.

A very brief mentions can be found in the book by Frans Caspar, Tupari, containing information given to the author by his Tupari informants about a ‘dangerous’ and ‘terrible’ tribe living in the forests to the east of their lands who they had never visited and who they called ‘Akontsu.’ The Akuntsu in question are indeed located to the northeast, and perhaps were located a little further to the east of the current Tupari territory.

Neither Akuntsu or Akunsu corresponds to the group's self-denomination. Rather, this is the name given to them by their Kanoê neighbours, survivors of the Kanoê groups contacted by the Rondon commission in the valleys of the Tanaru river between 1913 and 1914, who remained isolated in the Omerê forests until 1995 when they were contacted a short while before the neighbouring Akuntsu by the Funai ‘attraction’ team. The Akuntsu, in turn, call the Kanoê ‘Emãpriá.’

In the Kanoê language, Akuntsu appears to mean ‘other Indian.’ Hence the denomination ‘Wakontsón’ given to the mysterious tribe by the Tupari cited by Caspar may in fact be merely the term applied by the latter Indians to an indigenous group completely unknown to them, who perhaps had never even met them. Indeed in Caspar’s writings suggest that their dangerousness meant that the individuals of the group had never had the courage to visit them, meaning that their knowledge was based on oral information from the oldest members, dating from a time when reality and myth blur into indistinguishable events.

Population

In January 1999 a Funai technical group was set up to define the limits of the Omerê Indigenous Territory, inhabited by the Kanoê and Akuntsu, which delimited an area of 26,000ha with a 81km perimeter. The Territory was declared by the Ministry of Justice in December 2002 and awaits ratification from the President of the Republic.

Today the Akuntsu comprise one of the smallest ethnic groups in Brazil. Marked by the usurpation of lands and massacres, their history is little different from that of other indigenous peoples of Rondônia.

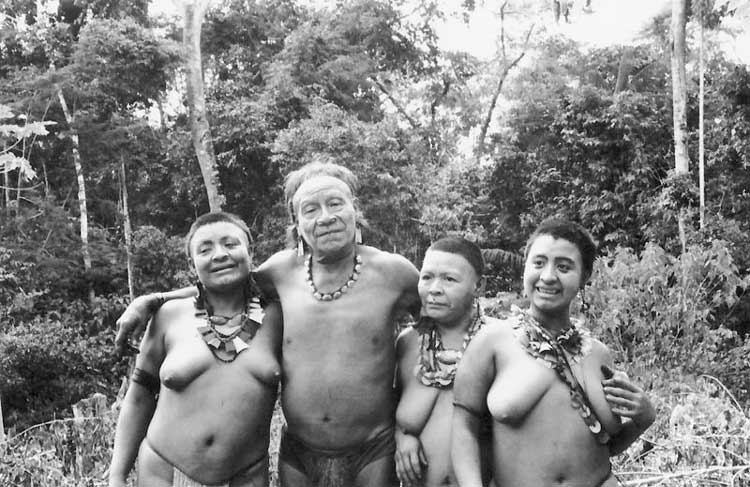

According to information given to ISA by the local Funai representative, Moacir Góes, in March 2005, the group is constituted by Kunibu (also known as Babá), a man about 65 years of age; Ururu, a woman aged around 75; Popak, a man of approximately 35 years; and three women aged between 18 and 30.

In the mid 1980s, the Akuntsu probably experienced their last large conflict with whites. Evidence found by Funai’s teams revealed that a massacre had taken place in the region’s forests, since they encountered various remains of tools and the traces of a village containing about thirty individuals. Ten years later, when the official indigenist agent contacted the Akuntsu for the first time, the account given by one of the members of the group, then composed of just seven people, explained to Funai's officers what had really happened. Kunibu recognized the pottery remains and some tools as items belonging to his former village and revealed clear details, including showing the scars on his own body showing what he described as the attempt to exterminate them. Kunibu gave an account of the attack that he and his people had suffered at the hands of white men who a long time ago had wanted to expel them from their lands. He also recalled with grief the names of the dead, which appeared to number more than fifteen.

Since official contact in 1995, the Akuntsu have lost one more person according to information supplied to ISA by Marcelo dos Santos. In January 2000, during a nocturnal storm, a large tree fell on Kunibu’s house, killing his younger daughter and injuring himself.

Contact history

As mentioned in the section on the group’s name, only one mention of the designation Akuntsu (more specifically, wakontsón) exists prior to official contact, in a text by Frans Caspar on the Tupari, indians of the Branco river, an affluent of the left shore of the Guaporé, who live to the southwest of the present-day Akuntsu territory.

Official contact

1985 saw the official creation of the Funai attraction team that would be responsible for the first contact with the unknown Indians reportedly occupying the Corumbiara region. Although Funai had known of rumours of these Indians since the 1970s, reports from 1984 reiterated the presence of one or more isolated indigenous groups in the tract of forest made up of legal reserves on some farms that had been deforested to sell timber and implant cattle ranching. The indigenous presence was continually denied by the region's farmers since, if confirmed, it would jeopardize the availability of the lands that were being developed for economic purposes.

In December 1986 the area that had been interdicted in order to attempt contact with the Indians was released to the farmers following the allegation from Funai itself that if Indians had existed in the region, they had already left, since the area was criss-crossed by small roads used to remove timber felled in the forest.

Despite the lifting of the interdiction of the area, over the following years the Funai officer responsible for the attraction team, Marcelo dos Santos, continued his search for traces of the indigenous presence in the forest. He frequently faced death threats and all the obstacles that the loggers, land-grabbers and farmers could create. In 1993 dos Santos began to make use of satellite images and based on a small red dot spotted in one of these images, interpreted by the Funai officer as a possible swidden, left on an expedition to contact the Indians definitively.

In September 1995 they contacted the Kanoê indians, survivors of the Kanoê groups already mentioned by the Rondon commission that used to inhabit nearby regions. In conversations with members of the contact expedition, the Kanoê related that nearby there was another indigenous group who they called the Akuntsu. In October the same year another expedition, which included some of the Kanoê, located relatively nearby the small malocas of the unknown Akuntsu, who, extremely startled, nevertheless greeted the group. They number seven people: two adult men, three women (an elderly woman and two of child-bearing age), an adolescent girl and a girl of about seven.

The presence of fear

Fear had become a constant element in the day-to-day life of the Akuntsu. Kunibu, the group’s chief, never approached anyone else without blowing first, a form of ritual action typical to shamanic rites that have the power to repel malefic beings or cleanse the body or environment where danger or a negative entity is believed to exist. This is his custom wherever he goes, such as while crossing the fields that divide the territory, a short journey invariably undertaken in Funai’s truck.

As mentioned, the Akuntsu and Kanoê lands are located on private land interdicted by Funai in the 1980s, and arriving at the Kanoê village requires crossing an area of pasture that separates the two islands of forest, a trip that takes 4 or 5 minutes. Due to the Indians’ fear of the farm workers, the trip is made in a truck used by the Guaporé ethno-environmental team (Funai). Likewise, when they approach the Funai attraction post, they usually become alarmed even when meeting they see frequently, as though expecting some kind of attack. All of this fear seems justifiable when we recall the history of the massacre to which they were subject: the bullets of the invaders are still today lodged in the bodies of Kunibu, his daughter and the three other women of the group, as well as Popak (the other surviving man). Fear is stamped on each of them, a fear of something that they have already suffered and whose causal element is found close by, in the pasture.

Material culture

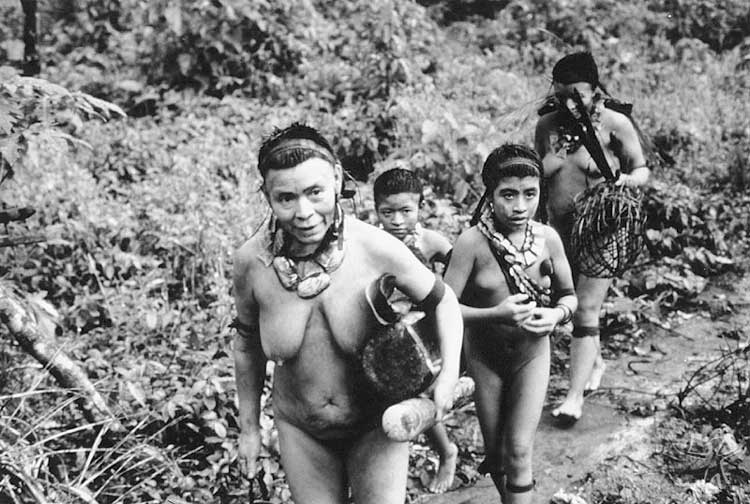

Like the groups from the Marico Cultural Complex, the Akuntsu manufacture a carrying bag made from tucum fibres with great care and application. Consequently, the marico may be a point of reference for tracing the historical contacts with other peoples between the valleys of the headwaters of the affluents of the left shore of the Pimenta Bueno river and the headwaters of the affluents of the right shore of the Guaporé, with whom they share many similar cultural aspects.

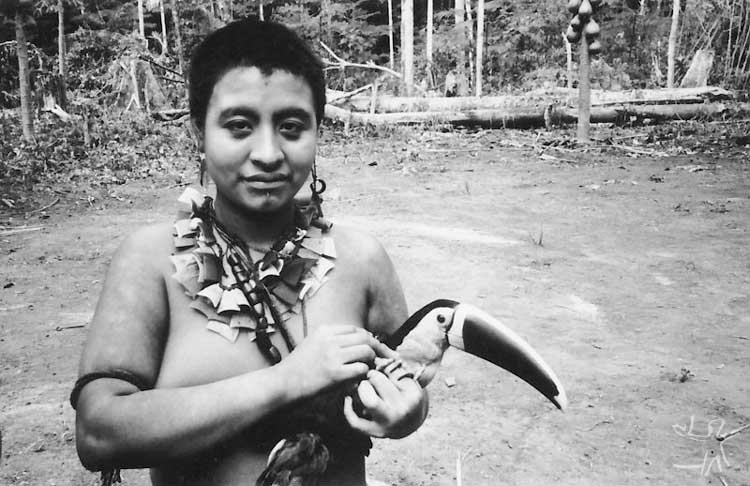

They make items of pottery and body adornments, such as cotton bracelets, garters and anklets, some with small appliqués of hide with bird feathers (toucan) and sometimes mammal teeth.

Today they make little feather artwork, aside from the nasal decorations, for which macaw feathers are commonly used, and the feather appliqués used on their arm and leg decorations.

Bows are made from a species of palm wood, while arrows are mostly fitted with a single sharp tip or with three tips, beautifully decorated with hand-dyed red threads.

The Akuntsu user river shells of various sizes and various types of seeds, which they use to make necklaces. Pieces of plastic are also used. The latter formed part of both Akuntsu and Kanoê culture even before official contact with Funai, and are cut in trapezoid or circular shapes to make the necklaces and shoulder belts they adore using everyday and to which they are strongly attached, since in the time before contact plastic was a reference to a successful raid on some barrels of chemical products, buckets and other objects made from the material, commonly forgotten in the farm fields or abandoned at outsiders camp sites. The colours pleased them immensely with a preference for blue, red, yellow and white.

Both men and women use a small loincloth with strands of inner bark in the same way as various peoples documented by the Rondon commission, such as the ancient Kepkiriwát. Distinct versions of these loincloths appear much further to the east of the Akuntsu territory, among the Rikbaktsa of the Juruena basin in northwest Mato Grosso.

The Akuntsu also make a bamboo pan pipe, used to compose beautiful melodies.

Ritual

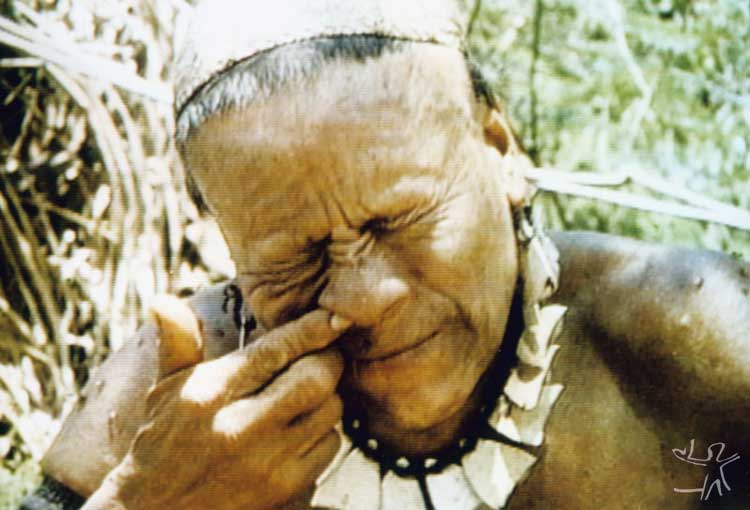

Shamanic sessions are an ever-present aspect of the ritual life of the Akuntsu. Kunibu, the group’s leader and shaman, interacts with a Kanoê female shaman in lengthy encounters that involve the characteristic shamanic blowing and inhaling of angico powder (snuff). They enter into trance and evoke the spirits of animals and fantastic beings, which they seem to incorporate.

Film footage taken in 2002 shows Kunibu and three women demonstrating what appears to be a ritual. Kunibu, holding his bow and some arrows, chants while stamping the ground firmly with his right foot, accompanied by the women who also hold bows and arrows, stamp their feet and repeat the melody sung by Kunibu.

Productive activities

The Omerê river does not represent an abundant source of food for the Akuntsu. They use it merely for drinking water and sometimes for small fish, which are enthusiastically celebrated and soon become an almost imperceptible appetizer. They meet the dietary needs through hunting, collecting wild fruits and cultivating a small swidden.

Game is found easily since the region has become an island providing refuge to animals from neighbouring areas already deforested for cattle ranching. Large bands of peccaries, tapirs and pacas wander through the forest and soon meet their fate on the tips of the Indians’ arrows. Peccary is by far the favourite game.

Note on the sources

The information provided in this entry come from notes collected in a field diary during a very short stay in the Igarapé Omerê Indigenous Land in July 2002. The sparse sources of information on this indigenous people and the short amount of time spent by myself in the Akuntsu malocas prevent any more detailed observations on this unknown group.

Moreover, the only significant text published on the Akuntsu was written by the anthropologist Virgínia Valadão for the volume Povos Indígenas no Brasil: 1991-1995 published by the Instituto Socioambiental. In it, the author describes the process of contact and the few bits of information existing on either group until then isolated on the Omerê river: the Kanoê and Akuntsu. Previously, the same author had produced an assessment report on the area of the Omerê river. However. in 1987 the indigenous group had not yet been contacted by Funai. In 1995, Maria Auxiliadora Cruz de Sá Leão wrote the report for interdiction of the Rio Omerê Indigenous Land, which contains information on the Akuntsu.

Sources of information

- CASPAR, Frans: Tupari ( Entre os índios, nas florestas brasileiras) – Ed.Melhoramentos - São Paulo - Brasil - 1958.

- VALADÃO, Virgínia. “Os índios ilhados do Igarapé Omerê”. In: RICARDO, Carlos Alberto. Povos Indígenas no Brasil: 1991-1995. Instituto Socioambiental, 1996.

VIDEOS